20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-001

Memorial at the Chechen-Dagestani border made out of empty tank shells for Russian soldiers killed in fighting with Chechen rebels.

Near the village of Andi, Dagestan, July 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-002

Russian nationalist youth celebrate the 200th anniversary of the founding of the town of Budennovsk. In June 1996, Chechen rebels took hundreds of hostages in Budennovsk.

Budennovsk, Stavropol Region, May 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-003

Backstage during a musical performance titled "For Peace and Understanding in the Caucasus.”

Makhatshkala, Dagestan, November 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-004

Distribution of humanitarian aid by the International Committee of the Red Cross in a former Russian "stanitza," a Cossack village. Most ethnic Russians left in the early 1990s; now many refugees from Chechnya live there.

Troitzkoye, Ingushetia, March 2002.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-005

A Dagestani policeman being presented by Russian President Vladimir Putin with "the Hero of Russia" medal for his bravery during the Chechen "Wahabi" rebel incursions, which were led by Shamil Basayev in August 1999.

Village of Botlikh, Dagestan, August 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-006

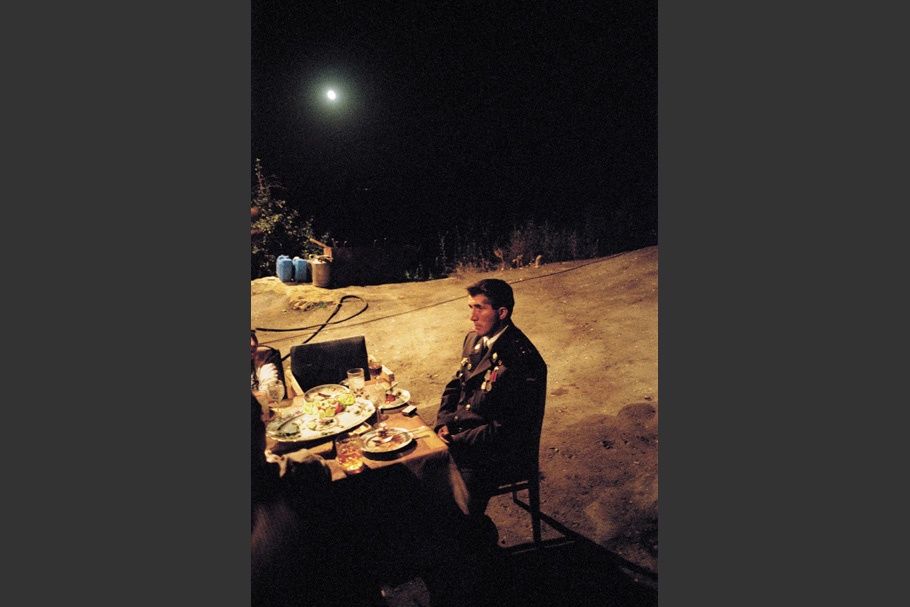

Local pro-Russian politicians and Dagestanis serving in the Russian military celebrate the 80th anniversary of Dagestan's incorporation into the Soviet Union.

Dilim, Dagestan, October 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-007

Chechen refugee children living in an abandoned train carrier.

Sleptsovskoye, Ingushetia, December 1999.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-008

Pro-Russian Dagestani militia hunting down alleged Islamist rebels who shot repeatedly at their checkpoints.

Near town of Kizlyar, Dagestan, November 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-009

Drug-addict couple on the shore of the Caspian Sea.

Makhachkala, Dagestan, August 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-010

Girl feeding a dog with sheep's blood in an Avar mountain village.

Gidatl, Dagestan, October, 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-011

Commemoration for the Dagestani soldiers and citizens killed during the Chechen incursion in August 1999.

Chechen border village of Agvali, Tzamudinsky region of Dagestan, October 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-012

A group of "Opolchentsy," local defense forces, commemorate the deaths of Dagestani soldiers and citizens killed during the Chechen incursion in August 1999.

Chechen border village of Agvali, Tzumadinsky region of Dagestan, October 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-013

A mentally disabled Chechen refugee child in a shelter.

Trotskoye, Ingushetia, January 2001.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-014

Dagestani Russian Interior Ministry troops killed three alleged Islamic militants who supposedly attacked Russian-Dagestani checkpoints near the Chechen border.

Near the town of Kizlyar, Dagestan. November 2000.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-015

Chechen refugees living in an abandoned train carrier.

Sleptsovskoye, Ingushetia, January 2001.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-016

Chechen refugee children living in an abandoned train carrier.

Sleptsovskoye, Ingushetia, December 1999.

20030130-dworzak-mw07-collection-017

Women holding photographs of missing relatives.

Born in Cham, Germany, in 1972, Thomas Dworzak began traveling and taking photographs in Eastern Europe and the Middle East while still in high school. After living in Avila, Prague and Moscow, and photographing war in the former Yugoslavia, Dworzak moved to Tbilisi, Georgia, and lived there from 1993 until 1998, covering the conflicts in Chechnya, Karabakh and Abkhazia. Although Dworzak moved to Paris in 1999, he continues to photograph the Caucasus and its people.

In 1999, Dworzak covered the Kosovo crisis for U.S. News and World Report. Following the fall of Grozny in 2000, he started work on a project about the impact of the war in Chechnya on the neighboring North Caucasus. During that time he also covered events in Israel, the war in Macedonia and the refugee crisis in Pakistan.

After September 11, Dworzak spent several months in Afghanistan taking photographs for The New Yorker. He returned to Chechnya in 2002.

He is based in Paris and Moscow and contributes to The New Yorker, Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, Paris Match and The New York Times Magazine. He has won several awards, including the World Press 1st prize Spot News Story Award, Prix Bayeux, Prix Kodak, Kodak Young Photographer of the Year Award, Prix Terre d’Images and the Scoop d’Angers. His work has been exhibited in the Musee de l’Elysee, Leica Gallery, Visa pour l’Image, Gallerie Generiques and Maison Doisneau.

Dworzak became an associate Magnum photographer in 2002.

Thomas Dworzak

In 1992, I moved to Moscow to learn Russian and take photographs. Not knowing much about the level of ethnic tension in the former Soviet Union, I was shocked by some of the racist rhetoric used to deride people from the Caucasus. Many Russians refer to Chechens and other Caucasians as “black asses,” holding them responsible for Russia’s woes. Officials use the term litzo kavkaskaya natzionalnost, or LKN, which means “face of Caucasian origin,” to classify and persecute Chechens living in Russia. Advertisements announcing apartments for rent read “won’t rent to LKNs,” and a sex advice column in a relatively liberal newspaper advises girls to pretend to be “scared of a big dog, a dead rat, or an LKN” to elicit affection from their boyfriends.

I decided to find out more about these people, and so traveled to prewar Chechnya, Abkhazia and Azerbaijan. Planning to stay for only a few weeks, I ended up living in Tbilisi, Georgia, for almost four years.

The Caucasus turned out to be neither a romantic paradise nor an all-out battlefield. I found an area that was incredibly diverse in culture, religion and geography. The people live under the most extreme contradictions. A region plagued by brutal wars is also home to a culture of zealous hospitality, a people who embrace the joy of life.

I was also there to cover the war in Chechnya. The first war had a sort of romantic appeal: the cruel Russian military machine versus a naïve, though corrupt, Chechen rebel army. But after the Russian withdrawal in 1996, Chechnya turned into an absolute “no go” area because of the numerous kidnappings by different factions in the conflict.

After moving to Paris, I returned to Chechnya in 1999 to cover the second Chechen war, which was in many ways more brutal than the first and much less accessible. Somehow I managed to document the disastrous exit of the Chechen fighters from Grozny in January 2000.

The idea behind the photographs exhibited here grew out of these bloody images. My aim was to show the war in Chechnya within the context of the North Caucasus. I photographed everything from the beginning of the renewed crisis in neighboring Dagestan, a Muslim dominated autonomous republic in the Russian Federation trying to strike a balance between the aspirations of its people and Moscow’s strong hand; to Ingushetia, another autonomous republic overloaded with several hundred thousand Chechen refugees; to North Ossetia, which has a Christian majority traditionally loyal to Moscow.

I have attempted to capture the culture of the North Caucasus, with its strange mix of appeasement and resentment toward Moscow’s military rule. Its people possess a strong desire for independence from Russia, which is often overshadowed by false memories of an idealized Soviet past.

—Thomas Dworzak, January 2003