20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-001

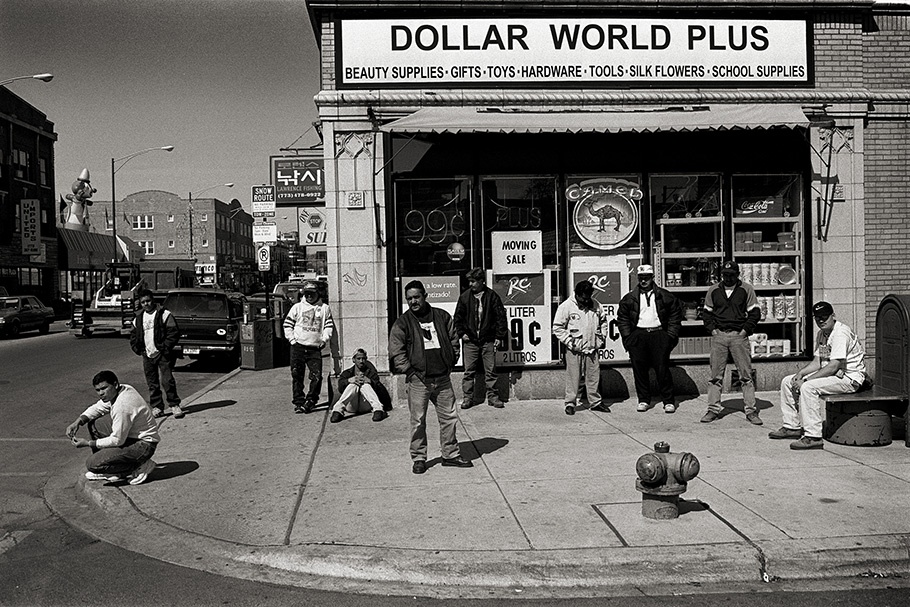

As early as 5 a.m., day laborers begin lining up for work—la parada—at the corner of Lawrence and Springfield Avenues. On a good day, perhaps two-thirds will find work. These men do all kinds of labor: demolition, roofing, pruning, watering, weeding, moving, plumbing, ditch digging, and more.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-002

Angelo Ojeda, from Morelos, Mexico, says he looks for work each day at the corner of Lawrence and Springfield in northwest Chicago. He and two of his friends were hired to dig a ditch in this heavy dirt for $60 for the day. He worried that his boss would not pay the money that he promised.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-003

When the owner of the building refused to pay the contractor, the contractor in turn refused to pay the workers. After being physically expelled from the building, Antonio Velazquez waits for the Chicago police to file a complaint. Velazquez says living in the United States is difficult, and he often feels like "doing something crazy."

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-004

Each morning at the corner of Lawrence and Springfield, laborers wait for contractors to arrive and offer them jobs for the day. Wages run from $5 to $12 an hour. The workers are often harassed by the police for loitering and are sometimes arrested.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-005

At the inauguration of the first Back of the Yards Worker Center at 4314 S. Hermitage, the Latino Union of Chicago held a barbecue. The Center, located in the back part of the Solis family home, was founded by the Latino Union to provide day laborers with an alternative to the many temporary employment agencies that dot the city and offer their employees only minimum wage and no benefits. Here Rosa Solis and cousin Ruben Solis enjoy the barbecue.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-006

Guadalupe Landaverde listens to Eliceo Zamorra Caballeros. Eliceo is a typical day laborer who is outspoken about the need to organize for better wages and working conditions. He and more than 75 day laborers testified before a Chicago City Council committee formed to investigate their plight. He says his fear of deportation prevents him from being as active in organizing as he was at home in Honduras.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-007

In the Niño/Guzman household, two people sleep in the living room, two in the front bedroom, one on the couch in the kitchen, and three in the back bedroom.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-008

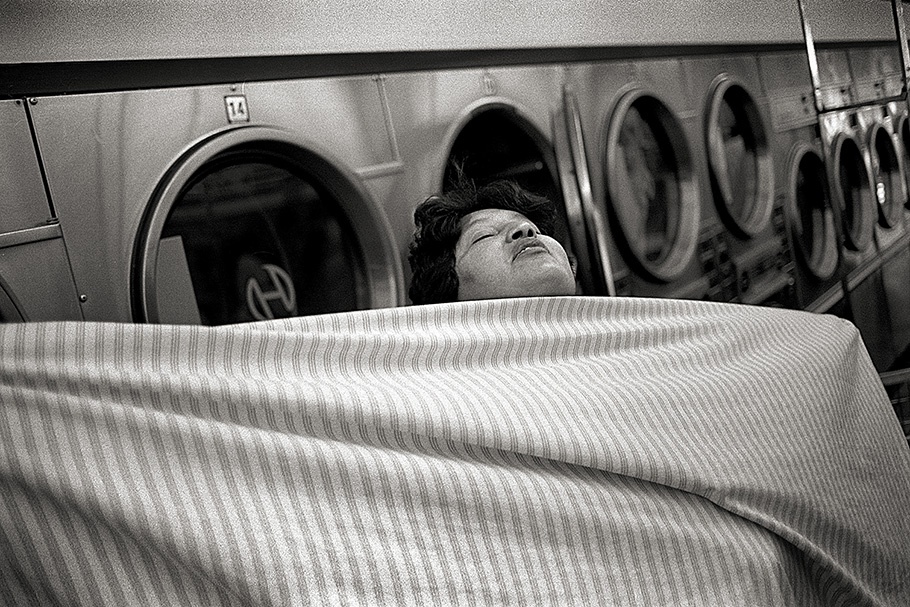

Remedios folds a sheet at the laundromat on 47th Street.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-009

Life in the United States, working long hours at the factory, and caring for a household takes its toll on Remedios. Here she sits counting $4,500 to send to a "coyote" who arranged passage to the United States for three adult family members now waiting in a Phoenix hotel room.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-010

Damian, 8, laughs after a pillow fight with his four-year-old brother, Nacho.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-011

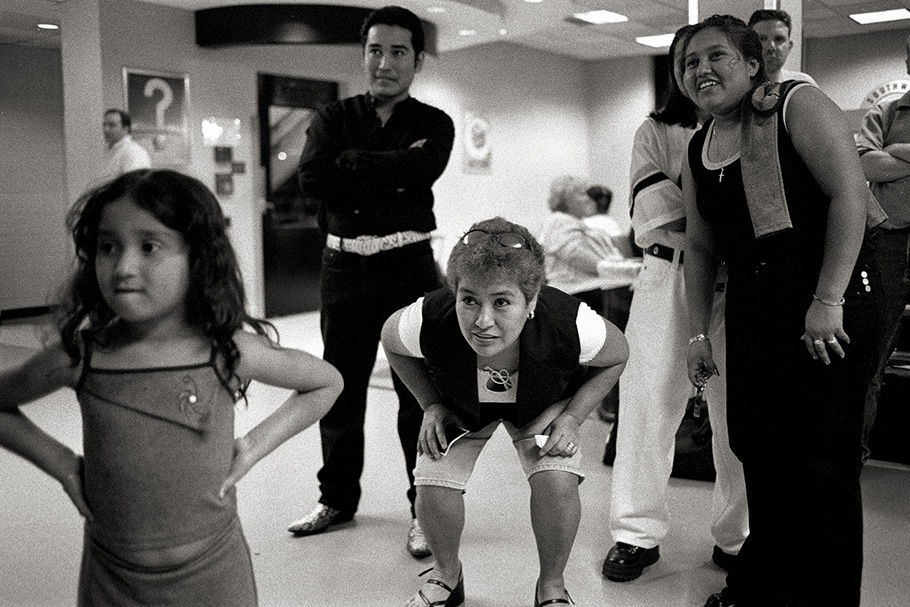

Lupe Guzman and her family wait at Midway Airport for her brother and two other family members to arrive from Acapulco, Mexico.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-012

Anselmo Niño waits with his son Nacho to pick up his wife Remedios from the Culinary Foods factory on Ashland Ave.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-013

Damian Niño touches his father’s bandage after the family returned from the hospital. For Anselmo Niño the past few years have been a challenging time. He has purchased land and a herd of cows in his hometown of Cuatro Bancos in Guerrero, but he has also lost his sight in one eye due to an unsuccessful cataract operation. He has had three operations, but now can only see shapes with that eye. He thinks that the doctor was negligent, but cannot find a lawyer who will file a malpractice suit.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-014

Damian Niño waits outside the school bathroom with his classmates. A year and a half ago, Damian arrived in the United States with his mother Remedios. Enrolled in the third grade, he is slowly learning English and Spanish. His parents had minimal schooling in Mexico so he has few examples of academic achievement at home, but his father Anselmo wants Damian to succeed at school.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-015

3:30 a.m. Christmas morning. Anselmo Niño argues with his nephew about various issues, ranging from drugs to spousal abuse.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-016

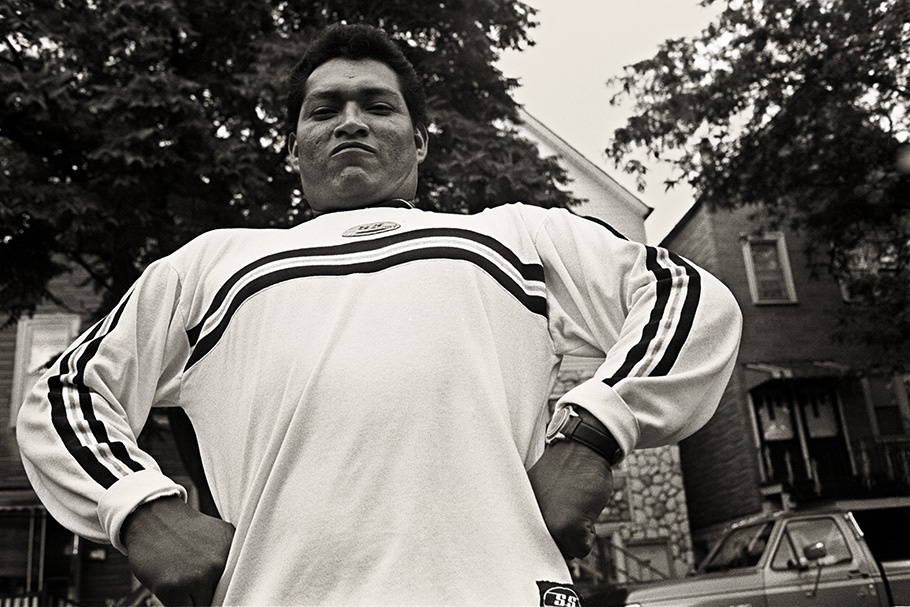

Señor Guzman.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-017

Miguel Niño dances with his mother Chavela during a late summer party at a family member’s house.

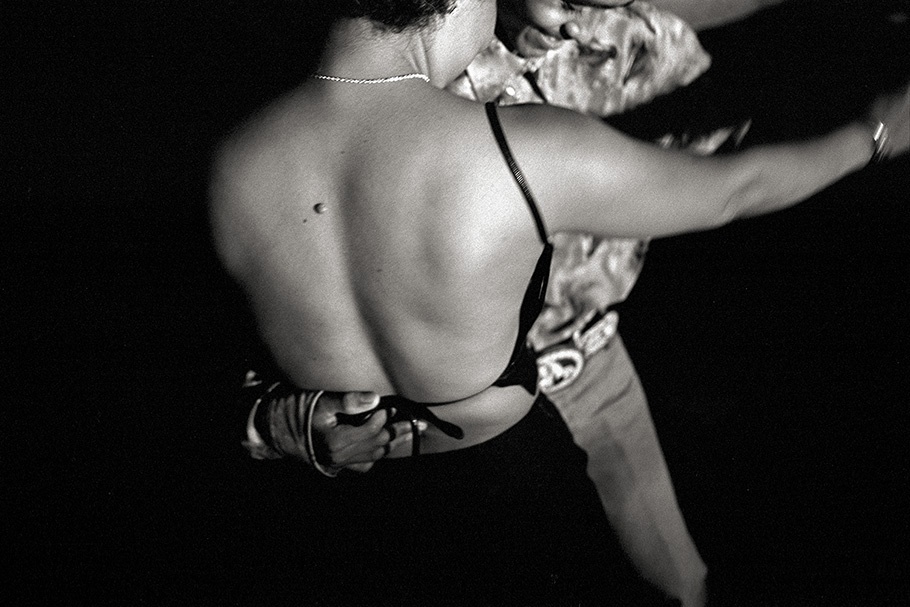

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-018

Roberto Niño with his fiancé at a baptism party for a family member.

20030130-lowenstein-mw07-collection-019

Juani Niño holds her son Jimmy at a birthday party over Labor Day weekend.

Jon Lowenstein was born in Brookline, Massachusetts. He attended the University of Iowa, graduating with a degree in English in 1993. Lowenstein has been a documentary photographer for more than ten years, exploring how and if photojournalism can effect social change.

In December 1999, he was chosen as one of eight staff photographers for the CITY 2000 (Chicago In The Year 2000) project, during which time he started an ongoing project on Mexican day laborers in Chicago.

Lowenstein’s work has appeared in Mother Jones, Time, U.S. News and World Report, Fortune, Elle, Ladies Home Journal, The New York Times, among others. Lowenstein has been a faculty member of Western Kentucky’s Mountain Workshop and the Southern Short Course.

He has won many awards, including the 1998 National Press Photographers Association Region 5 Photographer of the Year Award, the 58th Missouri Pictures of the Year Magazine Photographer of the Year Award and the Fuji Community Awareness Award. He is an associate member of Aurora Photos.

Lowenstein recently completed work on his first book, which explored the lives of developmentally disabled people in Illinois. He currently teaches photography at Paul Revere Elementary School and has been commissioned to complete a book about the school and the nearby community on Chicago’s South Side.

Jon Lowenstein

On May 8, 2000, Senon Guzman, Roberto Bernal and Jose Gonzalez arrived at Chicago’s Midway Airport. They carried no legal identification and no belongings except the clothes on their backs. The men shook hands with waiting family members, who had paid $4,500 to a “coyote,” a human smuggler, for the three men’s passage from Guerrero, Mexico, to Phoenix and then to Chicago. The family drove the new arrivals to a home on Chicago’s South Side. Within three days all three men had purchased false IDs and Social Security numbers and started working day labor jobs.

For more than two years I have photographed the lives of day laborers at work and at home. These photographs examine the multiple tensions in their personal lives and their complex place in the temporary employment sector of the new global economy.

The first and most visible form of day labor begins on the city’s street corners each day. Groups of men wait to be picked up by contractors offering construction work. The workers negotiate their fees on a per-day, per-job basis. They face numerous risks. Police periodically arrest them for loitering. Contractors sometimes pay them less than promised or don’t pay them at all. Three years ago, in Farmingdale, New York, two day laborers were hired, brought to a work site and attacked with knives and shovels by the contractors. The assailants have been charged with attempted murder.

The second form of day labor starts at a temporary employment agency or “oficinas.” In 2001, the Chicago Sun Times reported that since 1985 the total number of temporary agencies in the city had almost doubled to more than 217. The agencies appear more legitimate because they have storefronts and pay by check, but generally the pay is less per hour than what a worker can negotiate for himself on the street. The agencies often charge illegal fees for transportation, required safety equipment, or cashing checks.

Both forms of day labor offer no insurance, no health benefits and no job security. The minimum wage is the norm. The transient nature of the work and the illegal status of many workers make unionization and other kinds of labor advocacy almost impossible. Many workers fear immediate dismissal, deportation, or other reprisals if they raise labor issues with either the agency or the company.

According to some estimates, there are as many as 2 million day laborers in the United States. Prior to September 11, Mexican President Vicente Fox met with President Bush in Washington to discuss a limited amnesty for illegal Mexicans living in the United States. Since September 11 the political and economic climate toward legal and illegal immigrants has cooled considerably, affecting all day laborers. Yet a steady stream of undocumented Mexican workers continues to flow across the border.

The threats to immigrants’ rights give urgency to documenting and understanding this multilayered subject that concerns every country in the world. Senon Guzman and the other men are only a few of the millions of day laborers, but their story illustrates the effects of the new global economy on ordinary people and raises questions to which we all must find answers.

—Jon Lowenstein, January 2003