20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-001

Cordell crying crocodile tears after his mother’s friend Goldie has yelled at him.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-002

When Cordell was a baby, Fay graduated from a parenting program run by the Agency for Child Services. Fay then moved to the neighborhood and, after a short time, began using crack again. Neighbors reported Fay to ACS because of all the drug activity in Fay’s apartment and a social worker came to Fay’s door to see Cordell. Fay said that the boy was with relatives. As soon as the worker left, Fay sent Cordell off with one of the women who frequented her apartment to buy drugs.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-003

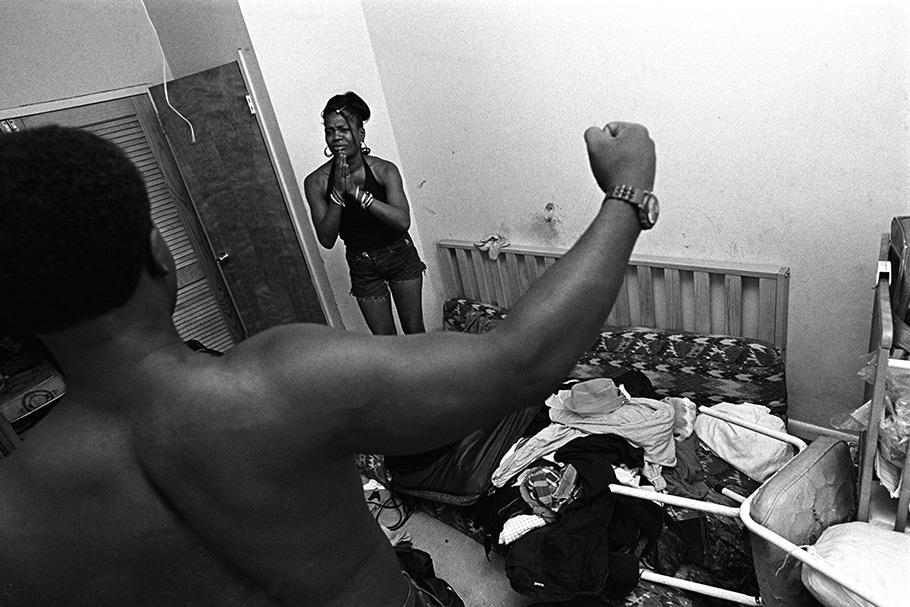

Cordell was eventually placed in foster care, and Fay’s apartment became a more violent scene. The dealers she sold for and often stole from used to only threaten her with violence, but after Cordell left they began following through on their threats. Her friends Shorty and Goldie moved out to live with one of Fay’s customers, leaving her alone, and Fay could not call the police for protection.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-004

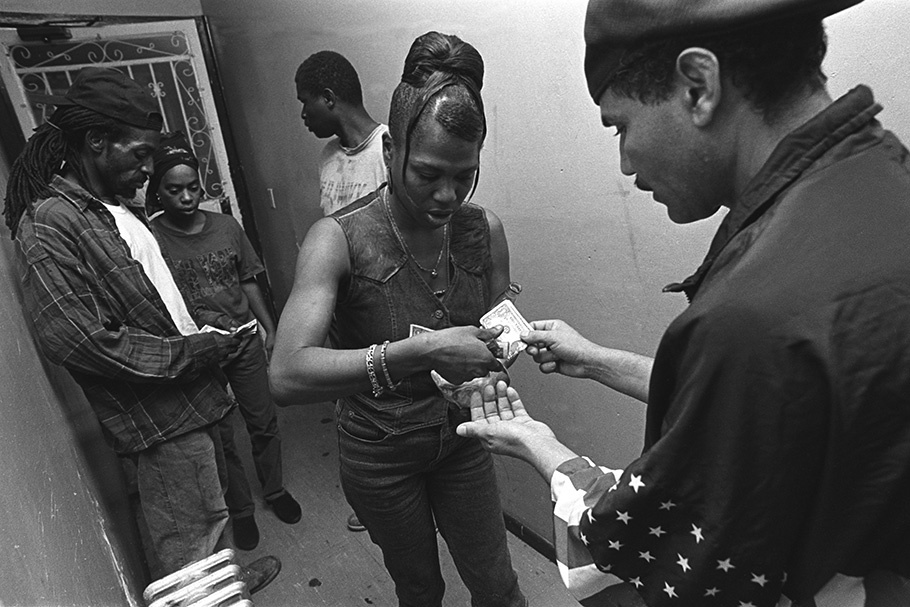

Since Cordell is gone, Fay shows little discretion. In this photograph she is serving customers in the hallway of her building.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-005

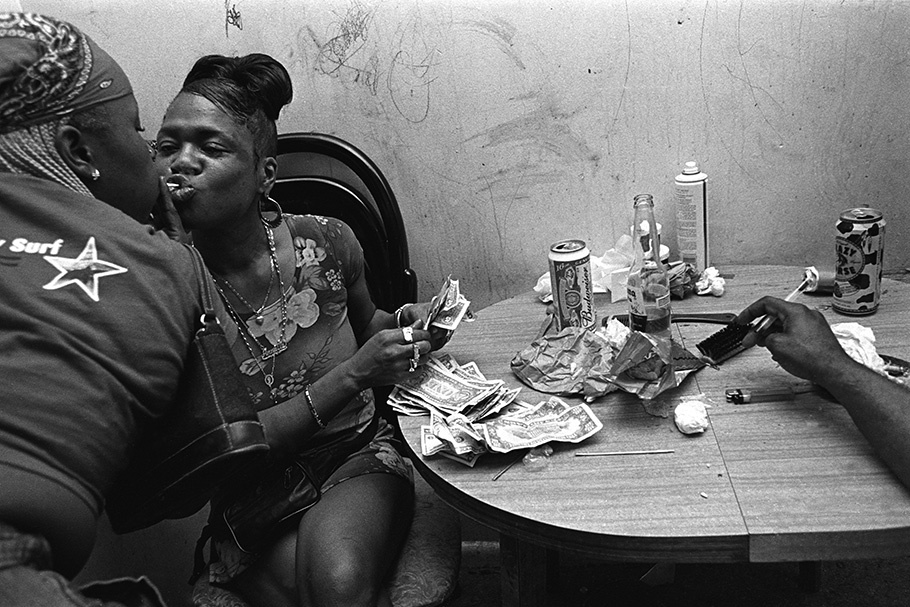

Fay has more hangers-on as she has more drugs and money passing through her apartment. She said that many women would offer to service her or clean her apartment.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-006

Fay had to leave her apartment soon after Cordell went into foster care, because her life was in danger. Staying with her ex-husband, she visited Cordell weekly. In June 2002, she went into a residential drug treatment program. Fay has not missed any of her court dates, and she was able to celebrate Cordell’s fifth birthday with him and his father at the foster care agency. Cordell started school in September 2002. Fay and Cordell will be able to reunite after Fay completes her program and satisfies the court’s requirements.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-007

Goldie’s mother died when Goldie was 16. Goldie’s mother was addicted to heroin and later crack cocaine. She contracted the AIDS virus through her addiction, and it ultimately took her life. Goldie, on her own since then, has attempted to numb the pain of her mother’s death by following in her footsteps. In October 2000, Goldie gave birth to her third child. Goldie usually survives by either providing or promising sex for money, but, at eight months pregnant, she prefers small-time dealing to other types of hustling. In this picture, she has rented a room for four hours and is resting before sampling and cutting up an eight ball of crack.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-008

Goldie is in labor at her friend Fay’s house, where she has been staying since she was six months pregnant. Goldie takes hits of crack in between her contractions and grasps her stem (a glass tube used to smoke crack) when the pain becomes too great.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-009

Goldie had thought that the baby was conceived during an unwanted sexual encounter when she was high. The suspected father later went to jail for setting his ex-girlfriend on fire for cheating on him. When Goldie first saw her daughter, she knew the child was not his. Goldie broke down for having blamed the child for who she thought the father was. Goldie names her daughter Jeanette, after herself; Goldie is her street name.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-010

Goldie leaves the hospital and is given 15 months to clean up, get an address, an income, and a plan for her baby. But she returns to the streets, the only life she has ever known. Jeanette eventually enters foster care.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-011

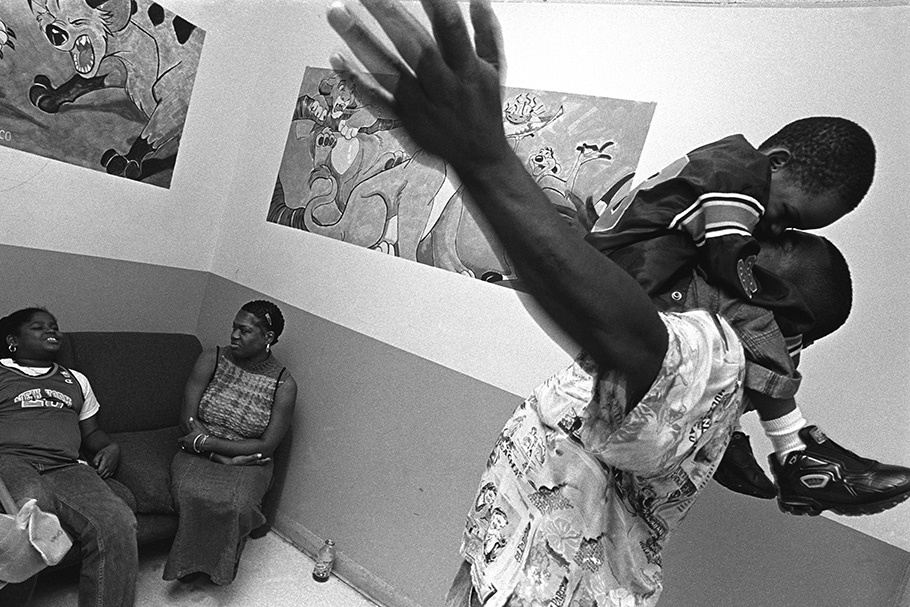

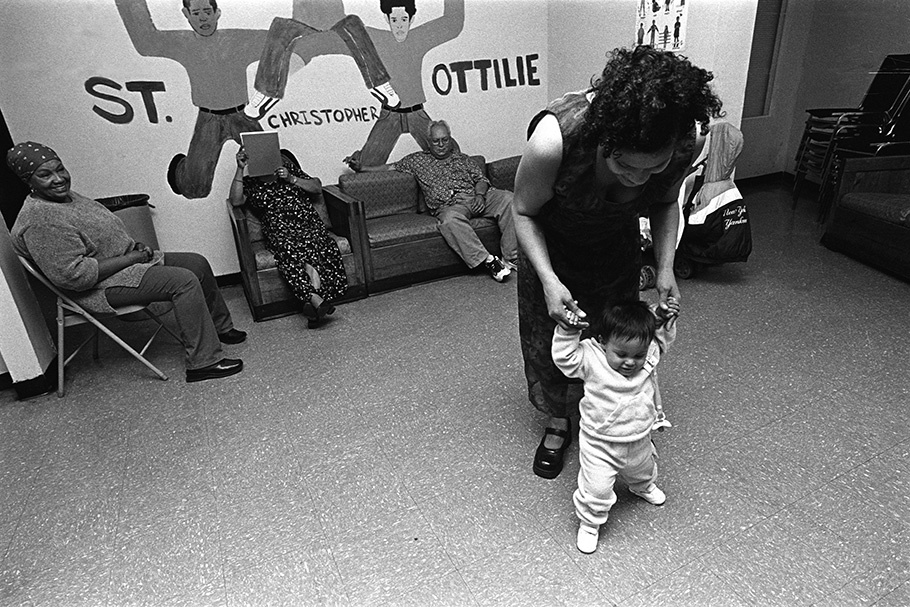

Goldie has biweekly visits with Jeanette at the foster care agency. Little Jeanette is about six months here and Goldie still has not entered treatment.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-012

Goldie met the love of her life, Shorty Dog, before Jeanette was two months old. Goldie became pregnant with Shorty’s baby not long after that.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-013

Goldie gave birth to Pricilla Jeanne 12 days before Little Jeanette’s first birthday. Little Jeanette’s foster mother agreed to take Pricilla to live with her and her sister. Little Jeanette celebrated her first birthday during one of Goldie’s regular visits to the foster care agency. Pricilla had her first official visit with her parents at the same time.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-014

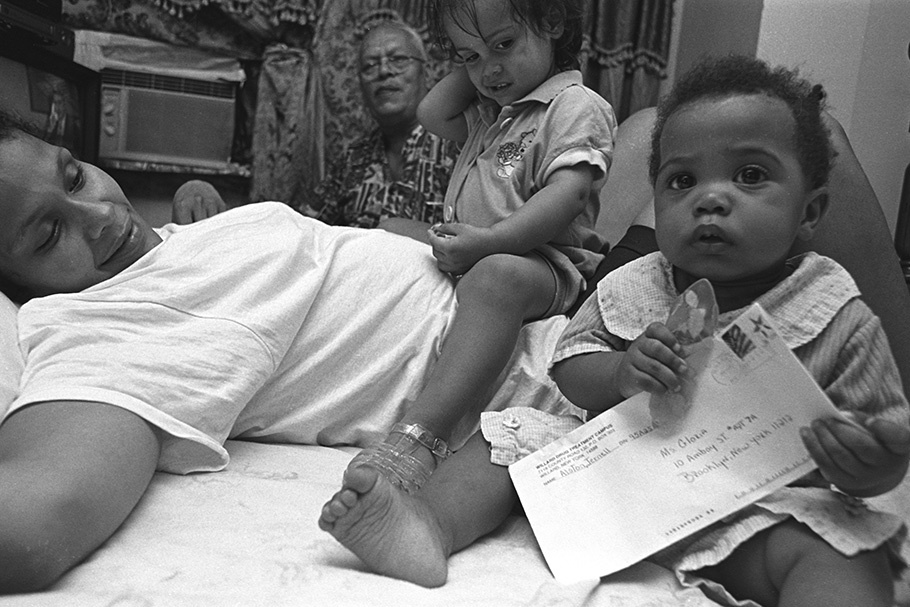

Shorty violated his probation and was sent back to prison. Eventually he got a chance to finish his sentence at a court-appointed drug treatment program. Pricilla, at the age of nine months, received her first letter from her father while he was in the treatment program.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-015

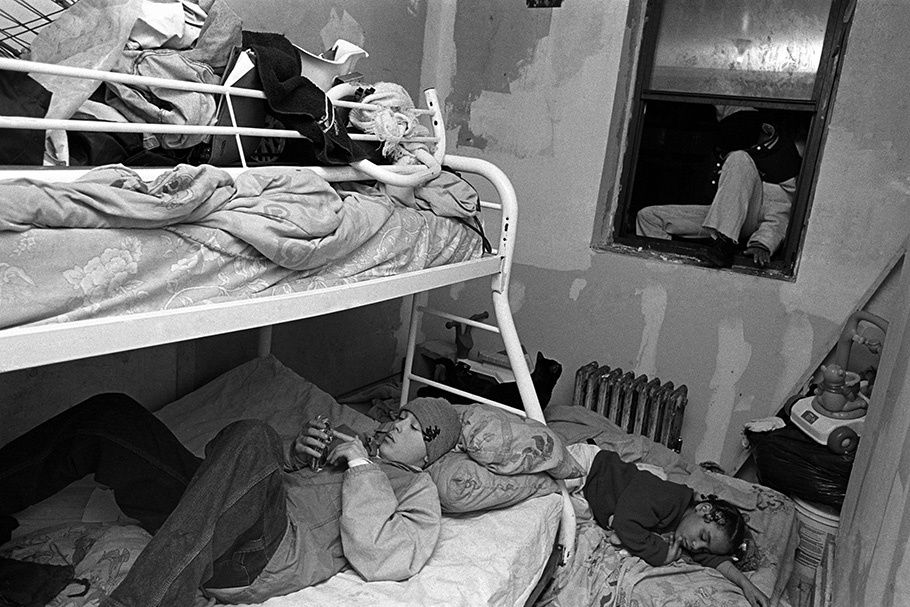

Tata climbing back through her children’s bedroom window in another attempt to avoid child welfare authorities, who barred her from her family’s apartment. Tata’s husband was told by his case worker that he must go to court to get an order of protection against his wife, a crack cocaine addict, or his children could be placed in foster care.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-016

Tony, Tata’s son, hears a stirring in the hallway outside his apartment and peeks out to find his mother sleeping in the hallway so as not to be found inside the apartment when ASC comes on one of their visits.

20030130-kenneally-mw07-collection-017

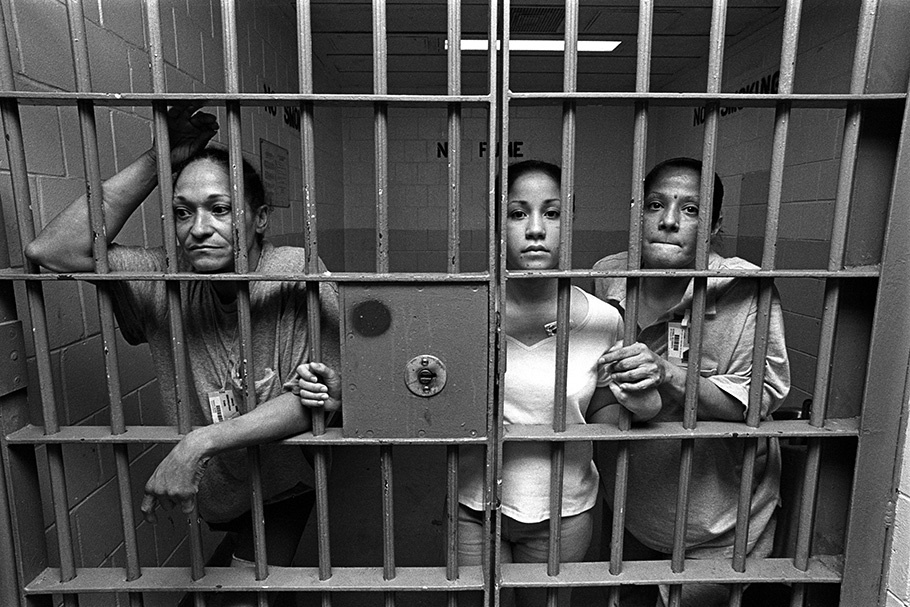

Tata was eventually arrested for selling crack cocaine. Because she is a repeat offender, she faces five to ten years in prison if she is not accepted into a court-appointed drug treatment program. To get into a program she must establish that she is in fact an addict, and that she only deals to support her habit. While at Riker’s Island awaiting trial, she met up with her brother’s wife and daughter. The mother and daughter had also been arrested on drug charges and the family had not seen each other for several years.

Soros Justice Media Fellow Brenda Ann Kenneally attended the University of Miami, where she earned a B.S. in Sociology and Photojournalism and New York University, where she received an MA in Studio Art.

Kenneally has been documenting the causes, effects and economy of the use and sale of illegal drugs in her Brooklyn neighborhood. The mother of an eight-year-old, Kenneally has focused on the way families can get lost in a culture of drugs and prison. She is searching for ways to motivate inner-city women to empower themselves, despite their limited social and economic opportunities.

Kenneally’s work has been featured in the New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, and Ms., among others. In 2000, her photographs earned the Community Awareness Award at the National Press Photographer’s Association Pictures of the Year, and in 2001, the International Prize for Photojournalism in Gijon, Spain. Kenneally’s work in Brooklyn has received the support of the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund, the Mother Jones Documentary Fund and the Nikon Sabbatical Grant and the Open Society Foundations.

Brenda Ann Kenneally

Ah, Brooklyn, the stuff that dreams—and photographs—are made of. By living and working there, I am following in the footsteps of photographers Helen Levit, Thomas Roma and Eugene Richards. I came to see what inspired them; I have stayed to see what will happen to the people that I’ve found.

Since moving to Brooklyn in 1996, I have photographed my neighbors and their families as they struggle with their physical, emotional and financial dependency upon a black market economy created by the use and sale of illegal drugs. The stories of Tata, Goldie and Fay illustrate the growing presence of the United States criminal justice and social welfare systems in the lives of inner-city families; in many ways, it seems as though these agencies have become members of these families, institutionalizing their children at birth.

My recent photographs depict how three women, limited in their social and economic opportunities, seek to empower themselves by selling illegal drugs, which only diminishes their self-worth.

Six years after taking the first photograph of Tata’s youngest son Andy, I am saddened by the direction in which his life is heading; I cannot leave until I see if this will change. I cannot leave until Tata stops climbing out her apartment window because the police are at the front door. I must stay until Goldie’s little girls get to wear the pretty party dresses that she never had.

And I will stay to see what my own life brings.

According to the teachings of the Buddha, what we see is an illusion; the only truth is that which we feel. At its best, photojournalism, which strives to capture our fellow beings in intimate, honest moments, allows us to feel the truth. It is only a pity if the feeling doesn’t transcend the photograph on the wall to change the way we see our lives.

—Brenda Ann Kenneally, January 2003