20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-001

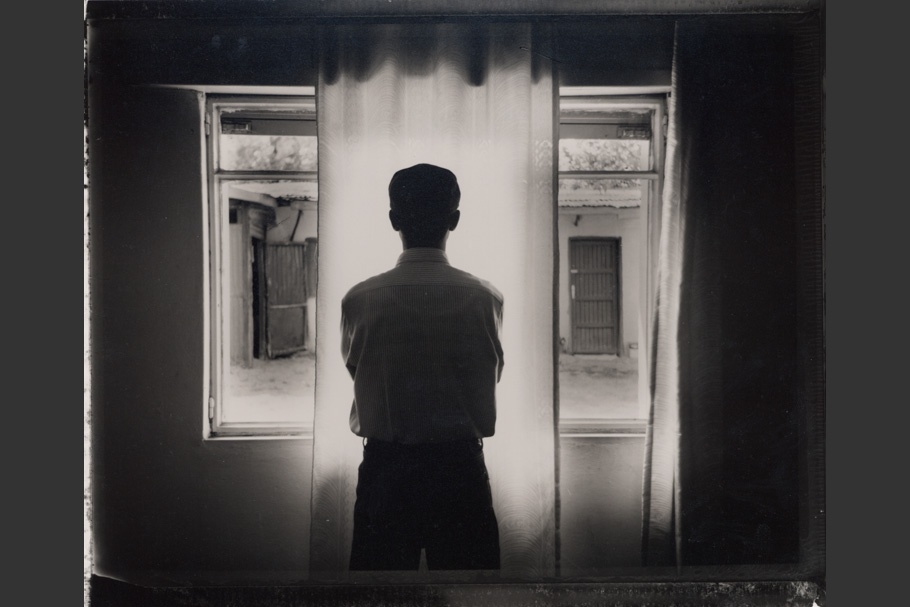

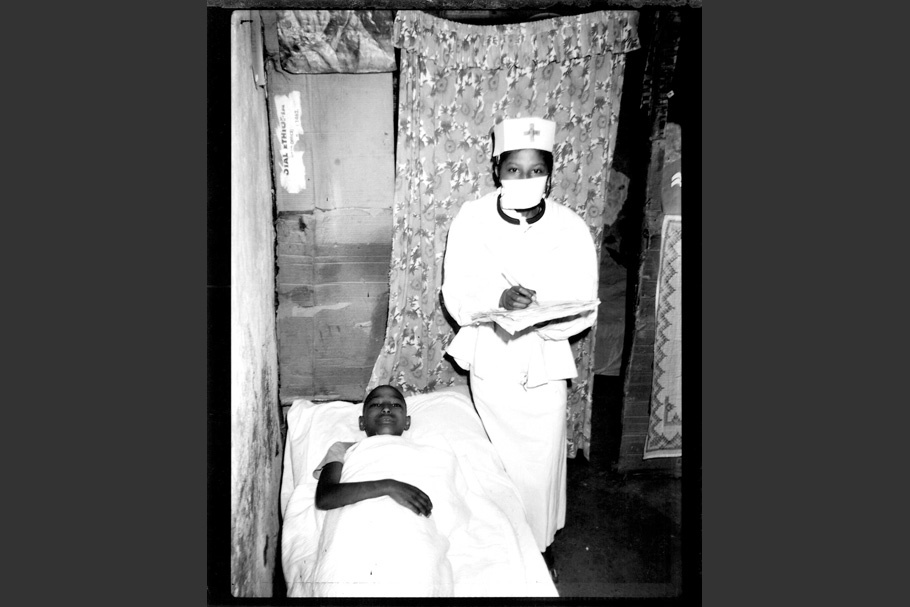

“Yonas”

She told me that she was to be blamed, it was her fault for getting the disease, that she had given it to me, that we would both die from it and that she was responsible. She told me she was sorry, that I have a right to be angry, that I could kill her if I wanted to.

But I did not want to. I wanted to hold her. When her shaking subsided, I told her that it may have been my fault. I had known a lot of women and her lifestyle was not what she would have chosen and I knew that. I knew she did what she did to support us, for our love, for me.

It did not matter who was to blame. We were together. We were made for each other. It had been a long time and we had endured too much to let this be between us. I swallowed all my own fears and breathed deeply and said to her, “We were created for each other. Finding this in our blood will not separate us.”

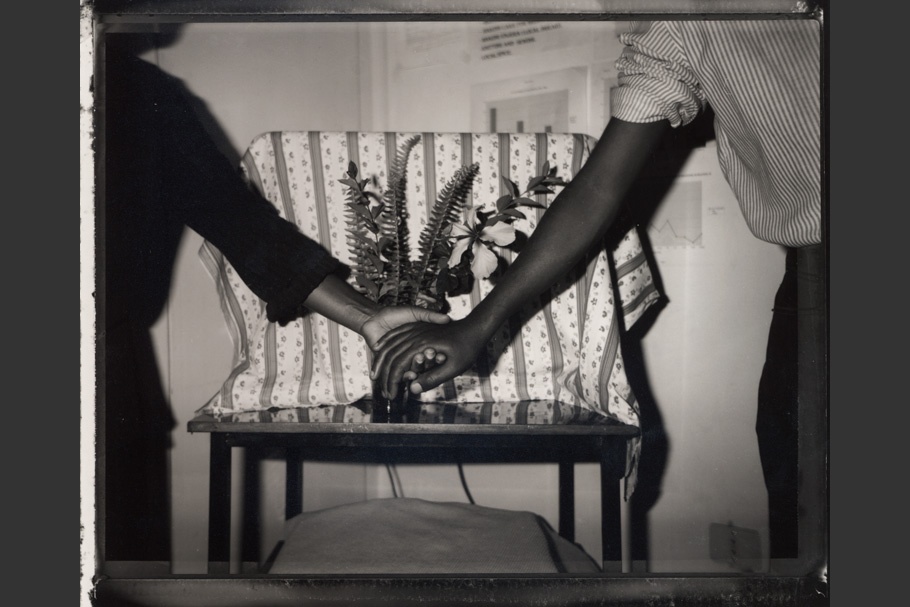

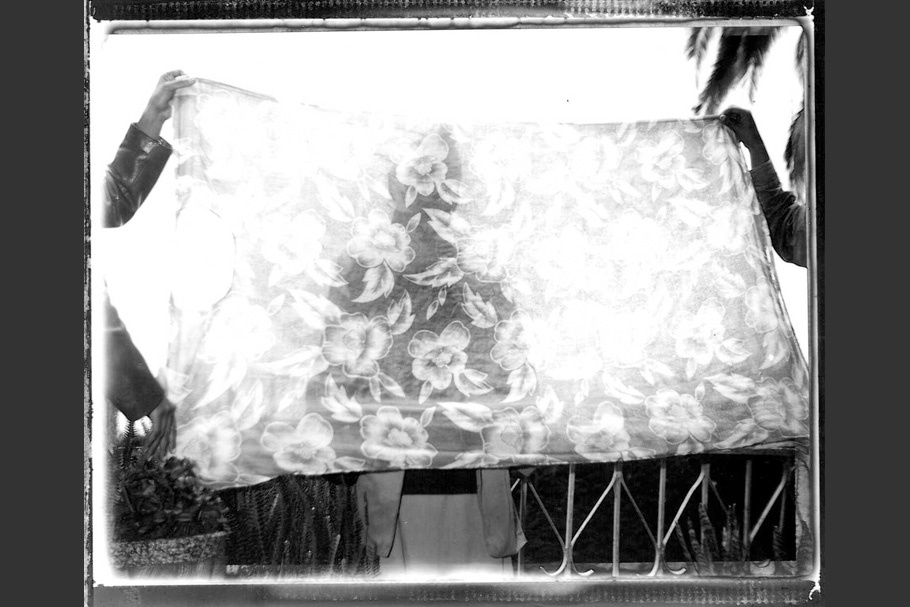

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-002

“Yonas” and his wife.

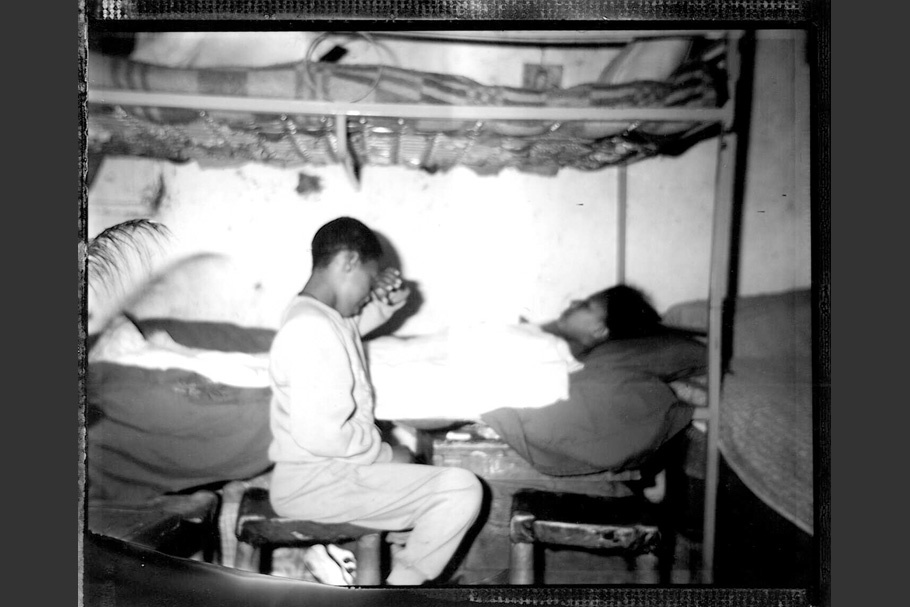

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-003

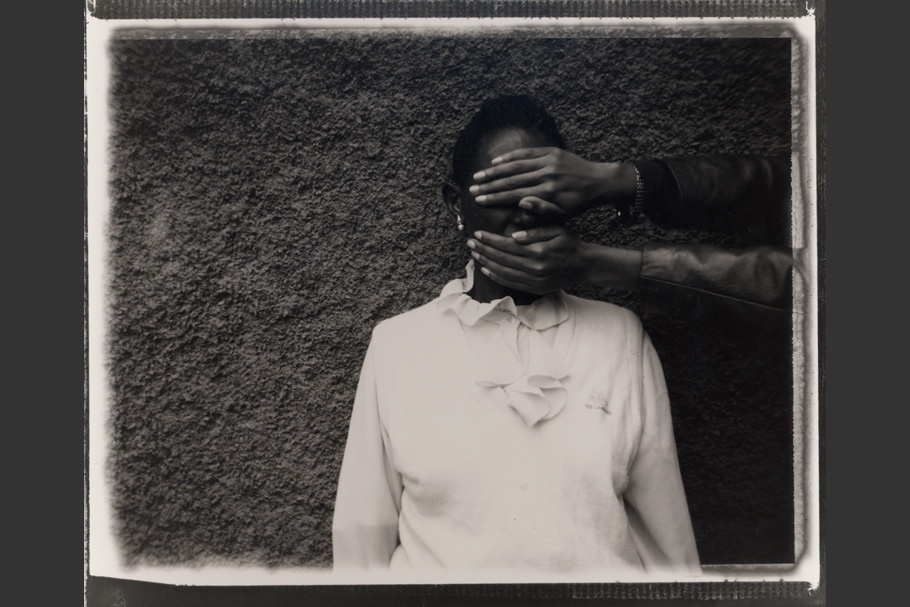

“Beletu”

People think life is easy, you know?

I think now about my husband.

If he had told me earlier, he wouldn’t have died as soon as he did.

We could have shared the burden together. I didn’t have any idea at that time.

This thing is so bad.

I would love to teach others now but I prefer to teach in some remote area, away from those who might recognize me.

See, society is narrow-minded.

Even those who are so-called “educated” are narrow-minded on this matter.

For example, I told my husband’s friend. He is educated. He had been to England and Germany.

I was hoping he might help my children when I die. However, I haven’t seen him since; he doesn’t even want to talk to me.

This is the situation.

My second child saw something on TV about AIDS and started laughing and joking.

Sometimes, I think about my children; who could teach them about this problem?

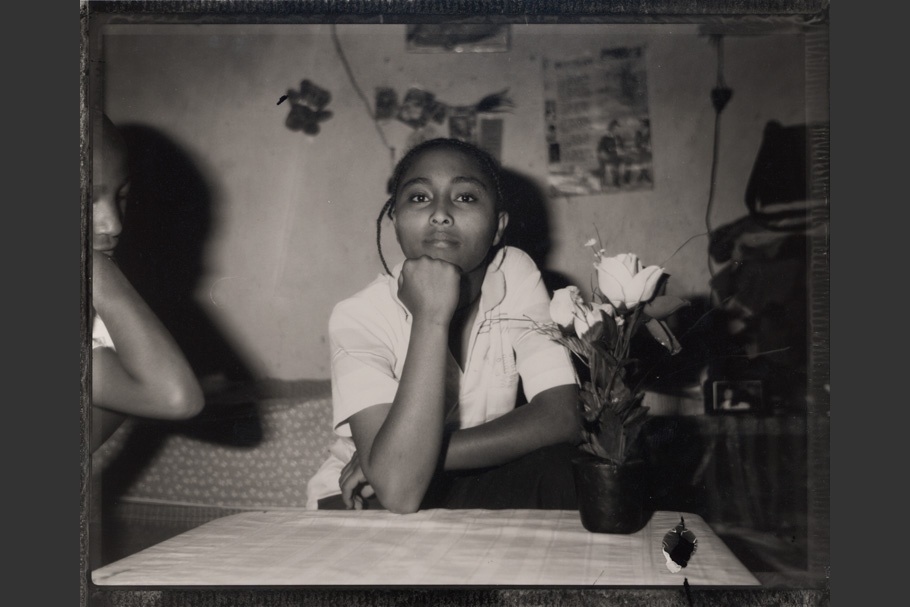

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-004

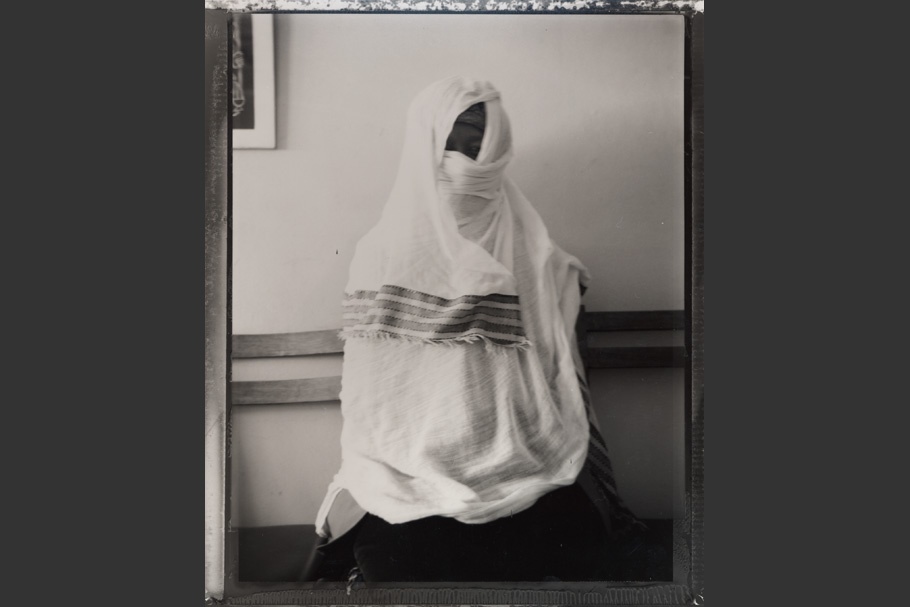

"Haregua"

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-005

“Hiwot”

I am twenty years old.

I was a street girl. Being a street girl is the ugliest job. I hated it but, because of my situation, I was forced to. My friends advised me to get into this kind of work. When I saw them making money, I tried it. I knew when I was a prostitute that there was a chance that I could get infected. But when you get into that kind of business, you have to trust in God to protect you. When I got sick, I stopped. They checked my blood and told me I have it.

I told only my sister. She wasn’t happy about it. I read her face and I could tell. I understood everything. After that, we didn’t talk about it. We didn’t talk about anything. Our relationship changed. I feel badly about it but I am hoping that God comes up with a medicine. I have friends. Our relationships are good. One of my friends has it. I act like I don’t have the disease. Sometimes I try to participate and tell them what I know. But if I start feeling badly, I leave. I want to be alone. It is then that I think back to what my counselor said: I’m not the only one, many others have it as well.

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-006

“Kidist”

I am not sick.

I don’t feel any pain. I worry about the stigma which comes with it. My family has very negative thoughts. They see it as very scary. They talk badly about it. There is such a phobia, a fear. But, it is just like any other disease. People die of the flu and all kinds of other diseases. My belief is that, if I was not dying from this, I could just as easily die from something else. I don’t think much about it except when I see it on the news or some other TV show.

A person could be sick or healthy but when death comes, it will come. So I don’t fear death. The biggest effect on my life is how I think about myself, especially because I am not working and staying home. I have things I want to do in the future. I had a plan. Now, just because I have HIV, this plan may be ruined. And it makes me upset. When I am invited to my friends’ wedding or see them having children, I think to myself that I will not be doing this in the future. My future is not like it was in the past. In the past, my future was different. All I want to do is serve God.

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-007

Asrat, self-portrait.

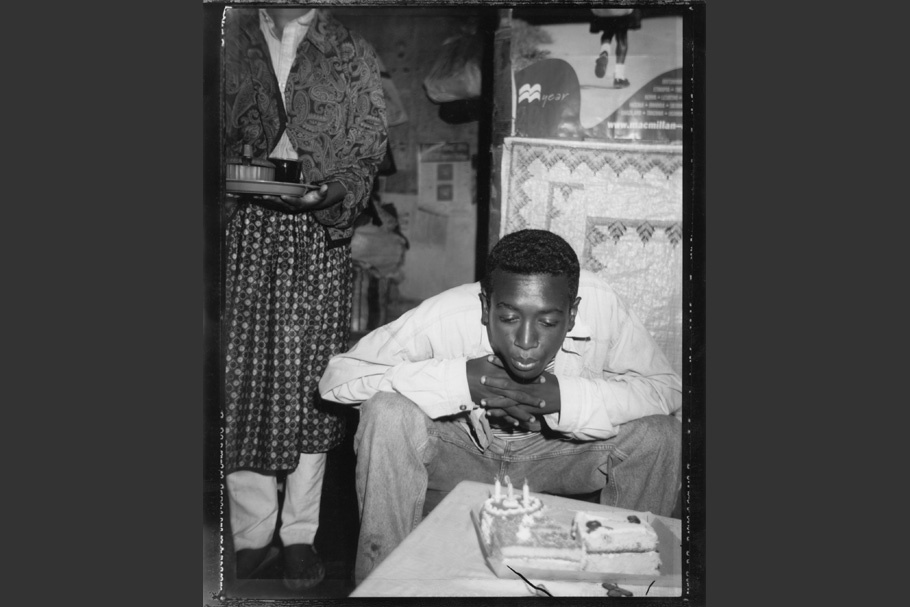

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-008

“At school, I dreamt our ESICE (college entrance exam) results came in and I got a 3.2 and was having fun with friends.” (A week later, Biniyam earned a 3.4 grade point average on his entrance exams, high enough for him to study law at Addis Ababa University.)

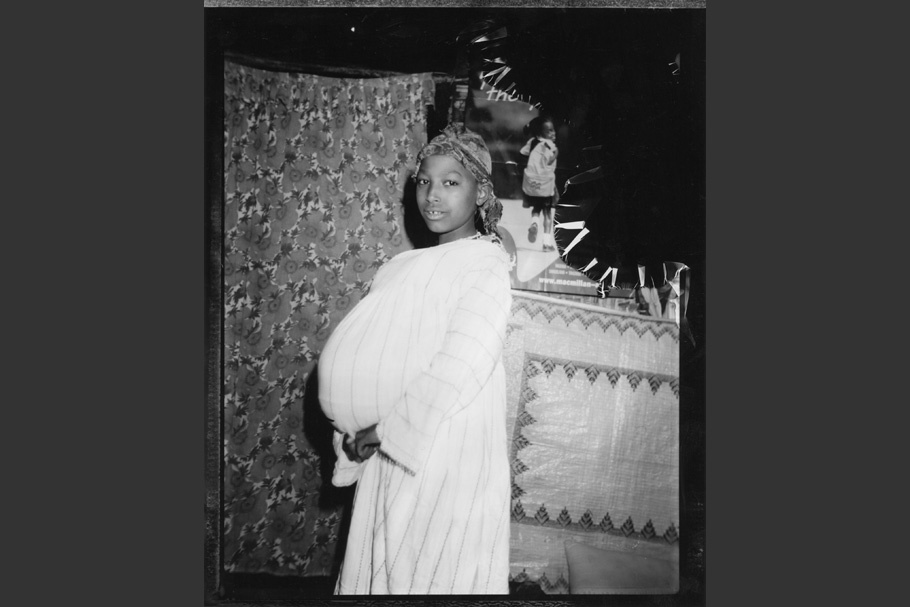

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-009

“When I get married, I want to have two kids: a boy and a girl. And I want to gather all the poor children on the streets and give them food, and have a car and a house. I will be sure to take good care of my children.”

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-010

“I want to be a doctor. After I get my medical degree, I want to study the latest technologies by traveling outside my country.”

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-011

“I saw Mami Dead.”

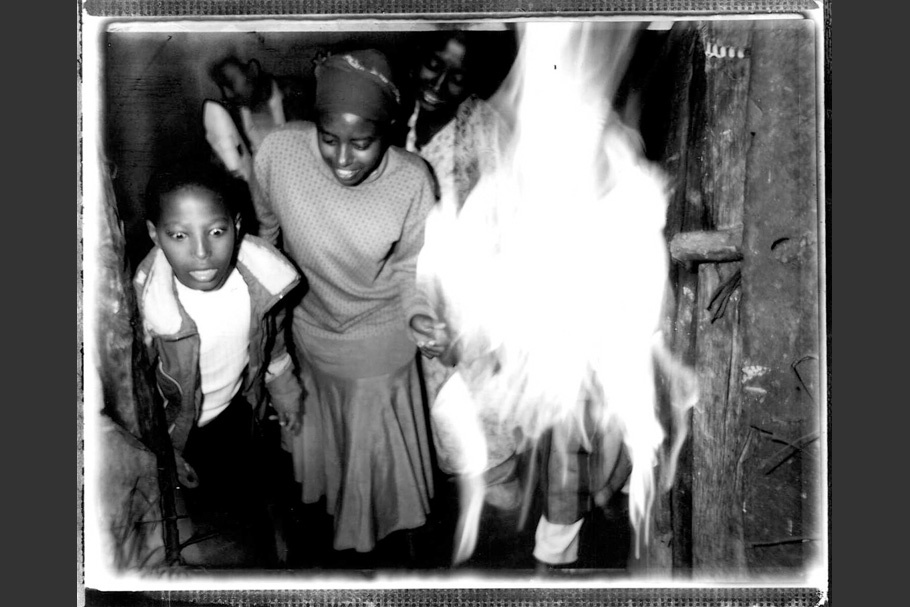

20030130-gottesman-mw07-collection-012

“One day, I dreamt Mami, Mami's friends and my sisters and brothers were sitting together and suddenly a fire began burning the house and we ran out.”

Eric Gottesman was born in 1976 and raised in New Hampshire. He studied history, literature and political science, with a specific focus on civil and human rights, at Duke University. Funded by a 1997 John Hope Franklin Award from the Center for Documentary Studies and advised by Doubletake cofounder Alex Harris, Gottesman began to develop his current approach to photography while documenting tourism in New Hampshire. Though he did not study photography formally, he has mentored with Harris, Wendy Ewald and Richard Misrach. After graduating from Duke, he led a team of researchers at the Supreme Court of the United States exploring the history of public reactions to constitutional issues.

In 1999, Gottesman received a Hart Fellowship to work in Ethiopia for a year. Fascinated by Ethiopia’s history of independence, he began a project about the effects of AIDS on Ethiopians’ visions of themselves. He plans to return to Ethiopia to continue work on this project.

Gottesman, currently based in San Francisco, has organized a salon of young photographers working on social and formal issues. He is experimenting with landscapes while continuing to explore documentary practice. Gottesman will be featured in 25/Under, a book profiling emerging photographers, to be published in 2003 by powerHouse. He is also working on a book for the Lilly Endowment, Seeing the Whole, about children’s vision of religion in the southern United States.

Gottesman’s work has been exhibited in Ethiopia, Kenya, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands and the United States at venues such as Addis Ababa City Hall, the United Nations Special Session on HIV/AIDS in New York and the XIV International AIDS Conference in Barcelona. In addition, Gottesman’s work has appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education, the International Herald-Tribune, Document, a U.N. World Food Program website and various NGO publications and academic texts.

Eric Gottesman

This Ethiopian proverb places self-respect above all else, even above basic needs. Ethiopian culture has historically placed a premium on self-respect and independence. And yet today, AIDS has caused some Ethiopians to hide their faces from others, and even from themselves.

I began this project wanting to dispel the notion that all people with AIDS in Africa are sick and dying. Naively, I set out to show people living with this disease—at work, at home, with their families—and to photograph them the same way I might photograph my own family going about daily life.

But this plan, in part, failed. Many Ethiopians living with HIV that I met had not told their families and were reluctant to speak with me. Many simply refused to be photographed, saying that they were afraid their employers might fire them, their landlords might evict them from their homes, or their unforgiving family members might disown them.

Out of necessity I developed a different documentary approach. Instead of making photographs of family life, I began to make portraits at counseling centers, omitting the subjects’ real names, and leaving them unidentifiable. Some participants worried that I would somehow manipulate the images to show their faces. In response, I used a Polaroid photographic process that was slow and deliberate. I often lugged a tripod and other cumbersome equipment with me. I used positive-negative film that develops both a print and a negative a minute after exposure. The subjects and I would look at the photographs together and decide whether their faces were truly hidden. If they were, I could use the image in exhibits and for publication. If they weren’t, we would dispose of the negative on the spot. This collaborative process allowed me to create images that express what the participants want others to see about their lives.

In addition, I taught photography to a group of HIV-negative orphans whose parents died of AIDS. Working closely with the children’s counselor, Yawoinshet Masresha, I asked them to make photographs about their own lives and to write about their experiences. The photographs they made, along with letters the children wrote to their deceased parents about what they had missed since they died, offer a glimpse of how the deaths of their parents have affected the children’s emotional development.

These two photographic series and accompanying texts reveal unexpected aspects of the disease that have had profoundly disturbing effects on societies. The first series describes the social and psychological stigma of AIDS—and the resulting silence about HIV. The second shows what happens when parents die from AIDS and a generation of children is left on its own.

In both cases, I placed a high priority on collaborating with the subjects of the photographs. The pictures form a portrait of what HIV/AIDS looks like from an Ethiopian perspective. We are invited to see Ethiopians affected by AIDS as they are seen by other Ethiopians and, consequently, as they have come to see themselves.

—Eric Gottesman, January 2003