20030130-sigal-mw07-collection-001

Kabul TV, using antiquated equipment, films a performance.

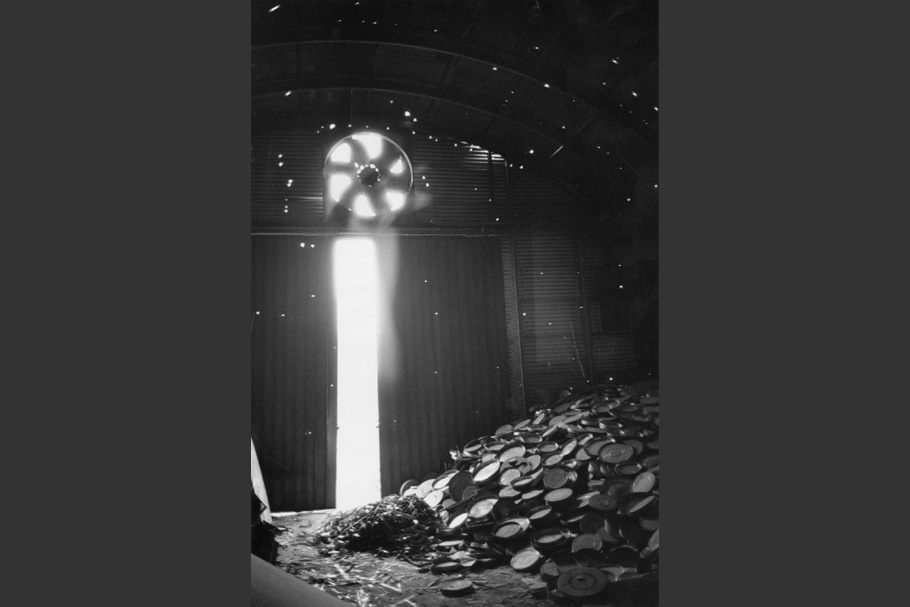

20030130-sigal-mw07-collection-002

Remains of Afghan Film archive in Kabul. The Taliban burned the archive before fleeing the city. Almost the entire archive is gone, except for a few originals saved by Afghan Film employees who stashed them behind a false wall.

20030130-sigal-mw07-collection-003

The projection room of Bakhtaar Cinema, Kabul.

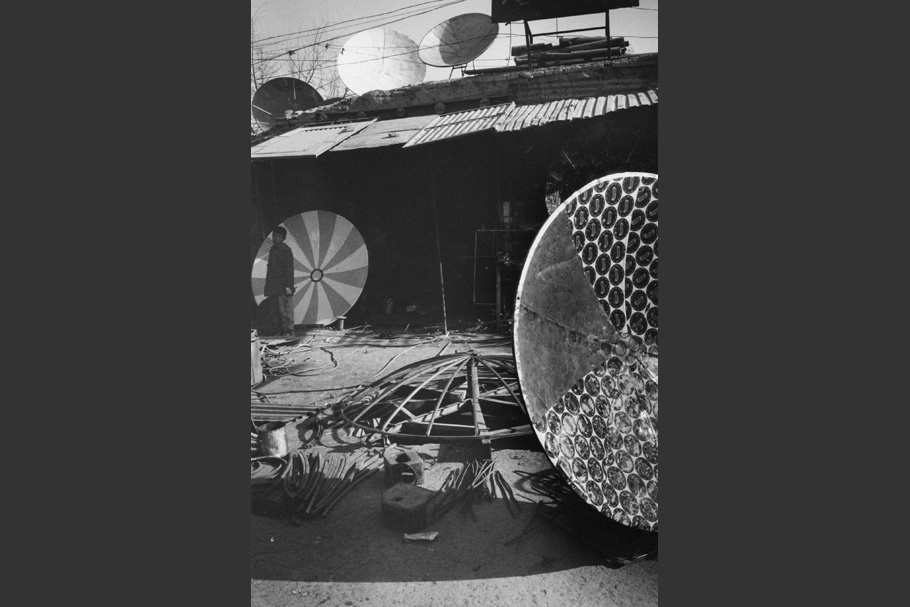

20030130-sigal-mw07-collection-004

Dozens of tiny workshops building satellite dishes have sprung up all over Kabul. Dishes cost as little as $60 and now adorn buildings throughout the city. As many as eight international channels are available at no cost.

20030130-sigal-mw07-collection-005

Spectators at Kabul Theatre, in a destroyed balcony.

20030130-sigal-mw07-collection-006

Spectators at Kabul Theatre.

20030130-sigal-mw07-collection-007

Musicians and dancers perform in the burned-out hulk of the Kabul Theatre. The theatre was destroyed during the fight for Kabul between Massoud, Dostum, and Hekmatyar. A small group of Afghan artists has begun giving weekly performances to promote the theatre's restoration.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1969, Ivan Sigal studied literature and art at Williams College and earned an M.A. in International Relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.

For most of the last decade, Sigal has worked in the countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. After receiving a Professional Development Fellowship in photography from the Institute for International Education, Sigal moved to Moscow to document the shifting social landscape in Russia, Ukraine, Chechnya, the Caucasus, Central Asia and Afghanistan. Since 2000, Sigal has been based in Kazakhstan where he directs media education and development projects for Internews Network in Central Asia and Afghanistan and works on a long-term project photographing Central Asia. In his photographic, television and radio work with Internews, Sigal seeks to influence as well as document issues, moving beyond the topicality and sensationalism of daily international news. Toward that end, he is the executive producer of the Central Asia TV reportage program Open Asia, broadcast weekly on more than 40 Central Asian TV stations.

Sigal’s photographs have appeared in the New York Times, Wired, Archaeology, Terra Nova, the Los Angeles Times, and the Fletcher Forum, among others.

Ivan Sigal

This story is time-bound. These images capture a brief moment in Afghan history when, shortly after the Taliban’s departure, the country began to refocus on itself.

Under Taliban rule, the culture of appearances that exists almost everywhere else—the photograph of a personal moment, the documentation of public events—was driven underground, surviving only in the backrooms of former photo galleries where Talib soldiers commissioned colored portraits of their lovers. For years, the only images that the world had seen of Afghanistan depicted war. Intended for foreign newspapers and magazines, these images appropriated the exoticism of poverty and misery for the hip foreigner’s psyche. But war is not the only face of the country and not the only face that Afghans, once again given the choice, will choose to portray.

With the Taliban’s departure, Afghans uncovered the lenses of their antiquated TV cameras, performed tentative, joyous parables on the stages of bombed-out theaters, and wielded homemade cameras on the streets of Kabul. People built homemade TV antennas to adorn their roofs, dozens of one-room shops manufacturing satellite dishes appeared out of nowhere, and hundreds of volunteers began to renovate Kabul TV and radio. Cinemas reopened and, for each of their thrice-daily showings, a rush of men crowded the entrances and fought for tickets for a long-awaited escape into fantasy. In both their homes and public spaces, citizens played music and danced without fear. Even as the foreign media swept through the country and rendered its exoticism neutral with a flood of nearly identical photographs of fierce, bearded men carrying Kalashnikovs, Afghanistan began to shed its status as an objectified culture. Afghans rediscovered their own vision by starting fresh conversations, relearning mass media conventions, and participating in a dialogue of images.

Nine months later, a portrait photographer on the streets of Kabul is unremarkable among a cityscape of scribes and shoeshine boys, stationery shops and apothecaries. Music bazaars have acquired an air of permanence, satellite dishes decorate buildings like jewelry, and everyone with pocket change has seen the latest Indian romance, twice. TV stations enjoy digital cameras, newspapers boast computers, and Photoshop is just another tool; the Internet is coming.

Mass media is another battleground for political conflict, images another weapon in that struggle. In Afghanistan, visual culture has once more become commonplace and, as in the rest of the world, continues its ubiquitous and seemingly inevitable march to cover the blank spaces of the earth.

—Ivan Sigal, January 2003