About Moving Walls 21

On display at Open Society Foundations–New York from January to October 2014.

The winter 2014 installment of the Open Society Foundations’ documentary photography exhibition series comes at a time when photography is becoming a regular mode of information sharing for many throughout the world. The medium is in a constant state of expansion and redefinition as new tools and technologies emerge.

In this context, citizen and professional photographers alike are seizing on new opportunities, but are also grappling with how to tell distinct and meaningful stories. Amidst the constant and cacophonous stream of visual information, how can a person capture the attention of others for longer than it takes to digest a single Instagram or Snapchat image? While eyewitness visual accounts uploaded and shared by ordinary citizens provide a wealth of first-hand information and personal perspective, what does a seasoned photographer add to our understanding of global events and injustices?

In contrast to the immediacy of images shared in real time, documentary photographers often commit to stories long term, creating narratives that have nuance and depth, and often challenge our assumptions or expand our knowledge. These stories explore the broader context and personal impact of global realities that we often only glimpse on the front page of a newspaper or a social media feed.

The photographers in Moving Walls 21 continue this tradition. Each considers how to visually represent an issue in a way that provides a new perspective on a story or place.

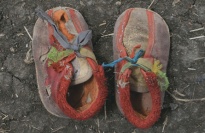

When Shannon Jensen traveled to refugee camps in northeast South Sudan in 2012, she aimed to highlight the arduous journey of hundreds of thousands of civilians fleeing conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile. Jensen wanted to avoid the dehumanizing and exploitative way that refugees and their suffering are often represented. She chose instead to focus her camera on the tattered shoes that these men, women, and children wore. For Jensen, each uniquely worn-down or patched-up pair of shoes not only reflected the individual struggles of their owners, but also spoke volumes about their ingenuity and perseverance during their long walk to safety.

Likewise, Diana Markosian shows present day Chechnya in ways that depart from mainstream coverage of this Russian republic, which continues to experience ongoing instability and conflict in the aftermath of two wars that lasted from 1994 to 2009. While most news reports focus on the overt violence there, Markosian shows the transitional nature of this region through the perspective of girls and young women coming of age in the context of an increasingly repressive environment. Through her intimate photographs, we are introduced to an array of young women, some who embrace and others who take huge risks to defy the Islamic fundamentalist government’s new decrees monitoring women’s behavior and dress.

Mark Leong, too, confronts distorted perceptions of a place on a much larger scale through his cityscapes of Hong Kong, which explore the tension between its reputation as a glittering, apolitical city driven by materialism, and the reality of its growing wealth gap and diminishing freedoms. This disconnect is placed within the context of Hong Kong’s increasingly uneasy relationship to China since the 1997 transfer of sovereignty from the United Kingdom to China. On rooftops and neon-bright street corners, at a park frequented by migrant laborers, and on the dashboard of a taxi operated by an entrepreneurial driver, Leong finds visual cues that signal Hong Kong’s distinct identity as it reflects on the traditions of the past and the challenges of the future.

With youth unemployment at 65 percent and millions of jobs lost, Greece is also facing uncertainty about its future. Nikos Pilos documents the impact of Greece’s economic recession in eerily serene photographs of abandoned factories and businesses in the northern region of Thrace. Since the mid-1970s, this region experienced a state-subsidized, but ultimately unsustainable, industrial boom. Once the economic crisis hit Greece, Thrace’s hundreds of factories were diminished to fewer than ten. Pilos’ photographs of industrial ruins are a reflection on Greece’s recent past and serve as stark reminders of the dangers of poorly-planned economic growth.

João Pina also considers the weight of history, in this case, the legacy of Operation Condor, a secret plan created in 1975 by the right-wing military dictatorships of six South American countries—Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay—to forcibly silence and remove political opposition. Pina unearths remnants of past atrocities embedded in the landscape, in family members’ stories, in legal proceedings, and in official documents and files. By combining his own photographs with a selection of archival images, Pina creates a visual history of a past that has been actively suppressed through extreme violence.

Together, these five bodies of work represent a range of visual narratives, and each photographer plays with varying degrees of intimacy and scale to tell their stories. By honoring this work, we hope to broaden and deepen viewers’ understanding of complex issues in ways that highlight both their global impact and their personal significance for those most directly affected.