20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-001

El Mozote, El Salvador, December 2001.

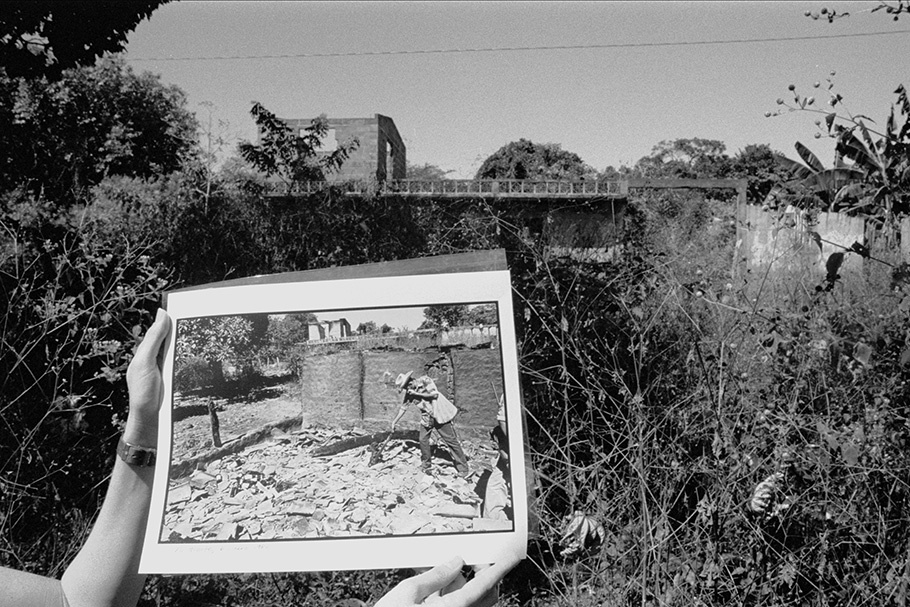

Photographer Susan Meiselas holds one of her photographs at the site where it was taken in early January 1982, weeks after the El Mozote massacre occurred. Meiselas's photograph appeared in the New York Times on January 27, 1982. The news of the massacre sparked an intense debate in the United States Congress, where the renewal of military aid to El Salvador was already the subject of controversy.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-002

La Joya, El Salvador, October 2001.

Anthropology student Miguel Nieva and forensic anthropologist Patricia Bernardi, members of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF), remove dirt surrounding the human remains found at the La Joya hamlet site. According to testimony by Sotero Guevara, he buried Pedro Chicas’s brother and his two sons wrapped in a hammock. He then placed them inside a hole he had already dug to protect himself and his family from the air bombing that began months before the massacre occurred.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-003

La Joya, El Salvador, October 2001.

Morazán community members working during the initial excavation process at the La Joya hamlet site.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-004

Cerro Pando, El Salvador, August, 2002.

Antonia Díaz presents her testimony to EAAF members Mercedes Doretti and Silvana Turner (standing). Antonia survived the massacre in Cerro Pando, a hamlet about 15 miles from the village of El Mozote. She was among the survivors who testified in 1990 on the killings that took place in Cerro Pando before San Francisco de Gotera's judge.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-005

La Joya, El Salvador, October 2001.

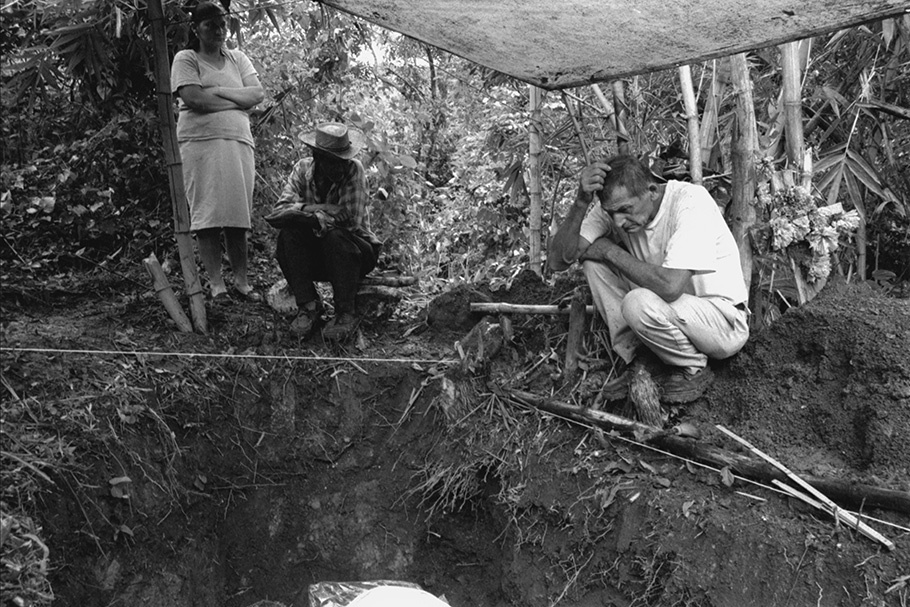

Pedro Chicas, a survivor of the massacre, watches the recovery of remains from a grave, only feet away from where his house stood in 1981. Standing next to him are his daughter Santos and Sotero Guevara, 75 years old and a neighbor of the Chicas family at the time the massacre occurred. During the exhumation, Sotero recalled in detail the sequence of events on the morning of December 16, 1981, when he returned to his house from hiding in a riverbank cave. Both Pedro and Sotero survived the massacre, buried relatives and neighbors, and presented their testimony before San Francisco de Gotera's judge in 1990, before the end of the war.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-006

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, November 2001.

Left coxal bone showing signs of high velocity bullet impact associated with skeleton 3 recovered from Los Toriles site 3, which belonged to a man 25 years of age at the time of his death.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-007

La Joya, El Salvador, October 2001.

Each skeleton found is carefully labeled and stored for later laboratory analysis. In this photograph, Patricia Bernardi and Miguel Nieva remove the remains of a boy believed to be seven years old at the time of his death. Using information provided by people who buried the victims and/or witnessed their burial, EAAF compiles a list of those believed to be buried at the sites investigated.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-008

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, November 2001.

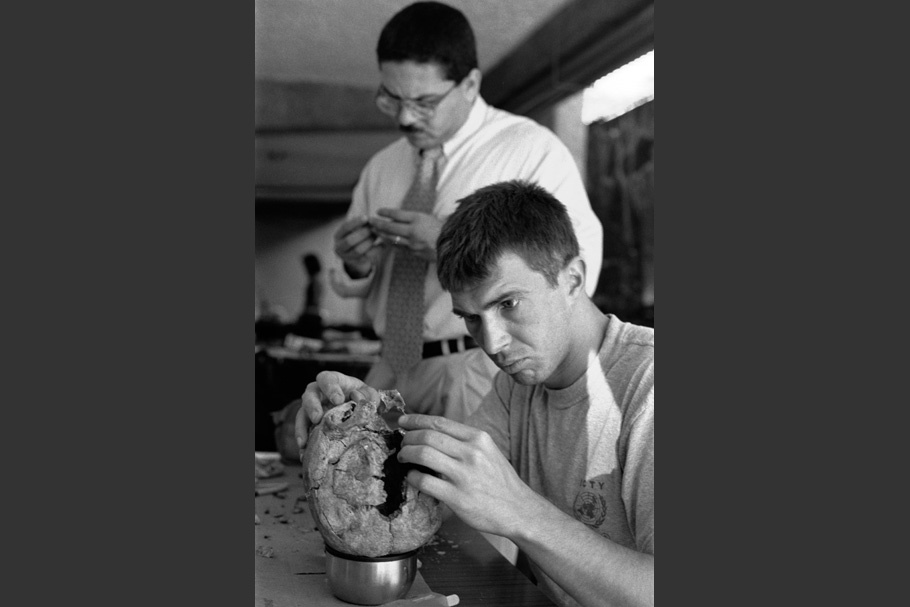

Miguel Nieva and odontologist Saúl Quijada, an EAAF collaborator, assembling fragments of a skull. This procedure will help to identify entrance and exit wounds, providing information about the cause and manner of death of the victim and, in some cases, the victim’s gender and age.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-009

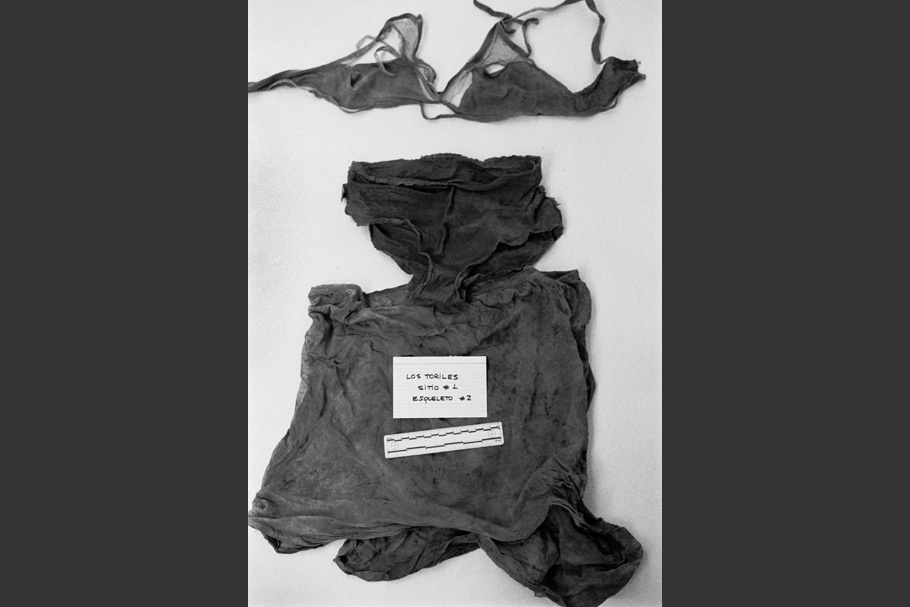

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, December 2001.

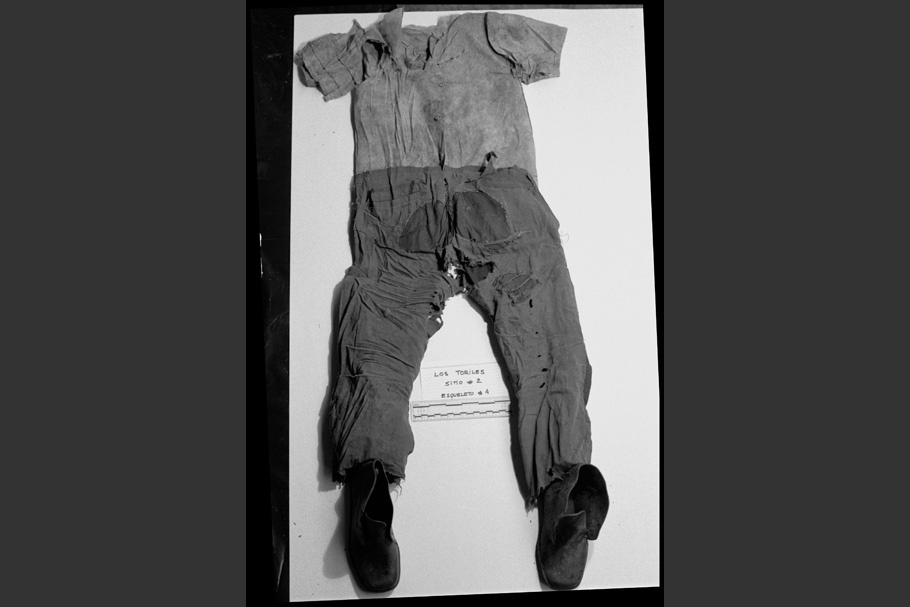

Clothing associated with the remains found at Los Toriles site 2, belonging to a child.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-010

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, December 2001.

Clothing associated with the remains found at Los Toriles site 2, belonging to a child.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-011

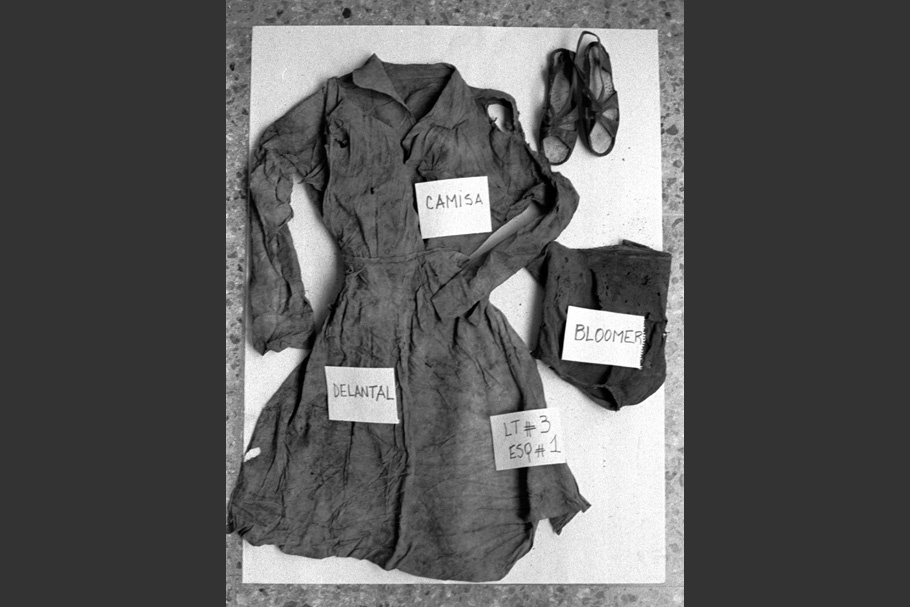

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, December 2001.

Clothing associated with the remains found at Los Toriles site 1, belonging to a woman 14 years old at the time of her death.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-012

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, December 2001.

In most cases, clothing associated with the remains of the victims is found in the graves. Forensic anthropologists write detailed descriptions during lab analysis, and these are sometimes compared with the testimonies of relatives and witnesses. Relatives can often remember the events of 20 years earlier in remarkable detail. In this photograph, the clothing is associated with the remains exhumed from Los Toriles site 3, belonging to a woman between 40 and 45 years of age at the time of her death.

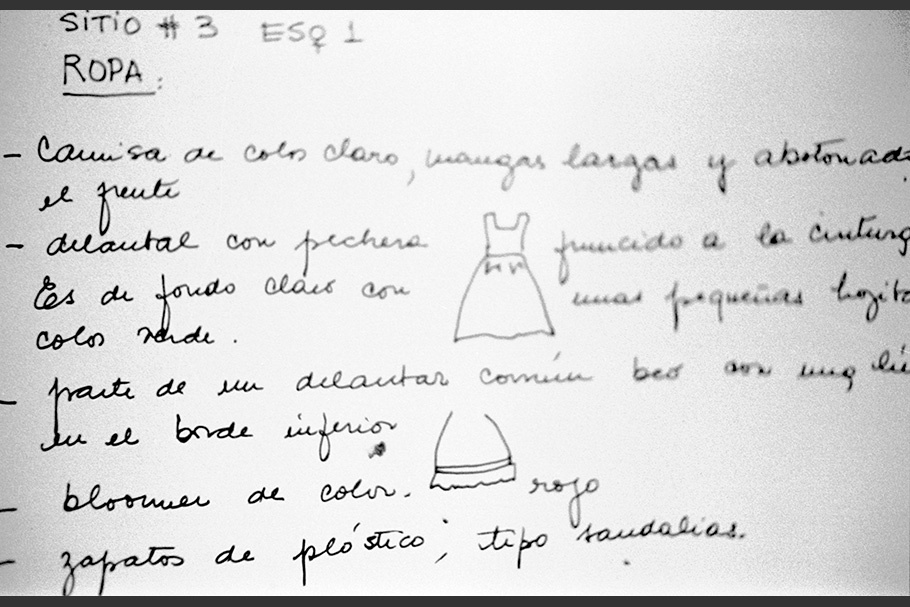

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-013

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, November 2001.

During laboratory analysis, EAAF members take detailed notes and drawings. In this photograph, the notes refer to clothing recovered from skeleton 3 of Los Toriles site 1, which are believed to have belonged to a woman who was 40 to 45 years old at the time of her death.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-014

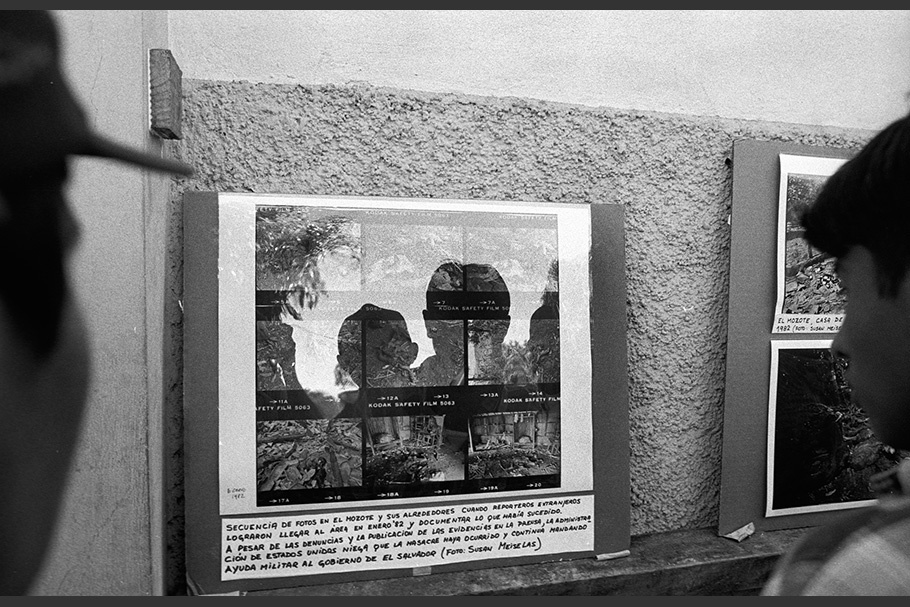

El Mozote, El Salvador, December 2001.

Members of the Morazán community observe Meiselas’s photographs. December 2001 marked the 20th anniversary of the massacre at El Mozote. Approximately 800 people from El Mozote and nearby towns attended a reburial ceremony for the victims exhumed that year; many people originally from the area migrated to other parts of the country during the war. With the permission of community leaders and priests, these photographs were hung on the walls of the church. Many attendees gathered to view these images for the first time.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-015

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, December 2001.

Clyde C. Snow, one of the world’s foremost experts in forensic anthropology, discusses with EAAF members Patricia Bernardi and Anahi Ginarte and EAAF collaborator Pablo Mena the possible cause of death of a skeleton recovered from Los Toriles. Snow trained current EAAF members in 1984, as well as other forensic teams, and continues to work with them in other countries.

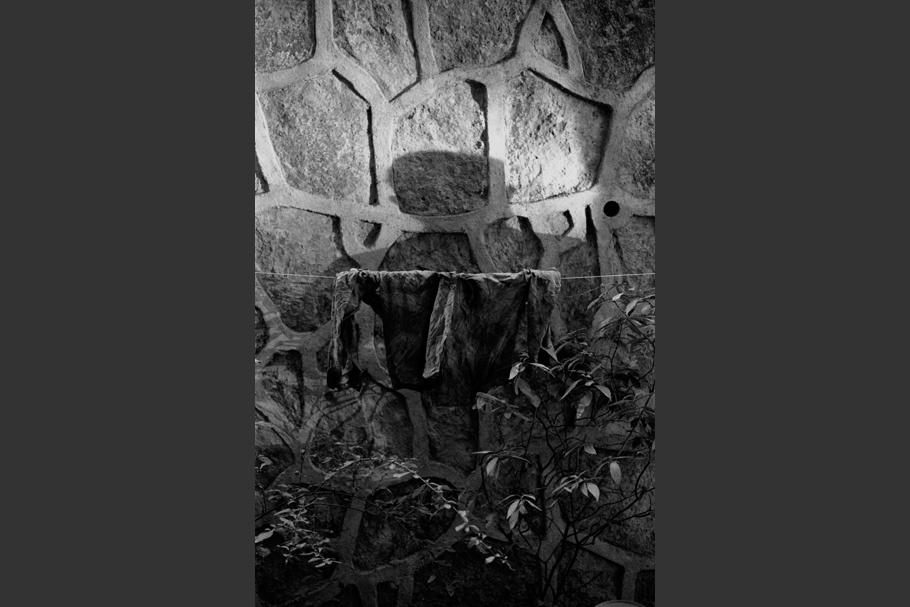

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-016

Institute of Legal Medicine. Santa Tecla, El Salvador, November 2001.

A shirt recovered from the Los Toriles site hangs to dry in the hallway.

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-017

El Mozote, El Salvador, December 2001.

A relative of one of the El Mozote victims holding a candle during the reburial ceremony in the new village plaza. Twenty years after the massacre of El Mozote, the act of finally burying the dead is very important in El Salvador as it is in other countries where such events took place. One 18-year-old woman explained how it felt not knowing where loved ones are buried: "One doesn't know where to put the flowers."

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-018

Jocoaitique, El Salvador, December 2001.

Pedro Chicas and his family at their house posing for a photograph they requested to have taken during the vigil for Pedro’s brother, Anastasio Chicas, and his two nephews, Jacobo and Justiano Chicas Martinez. In the front row are David, Rosa, Santos, Pedro, Ana, Valerio, Noé and Carmen.

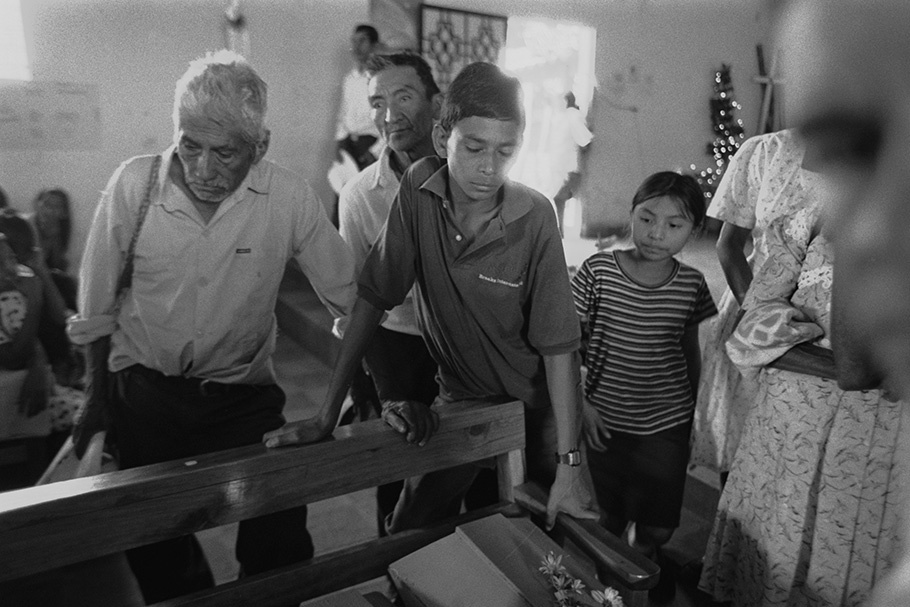

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-019

El Mozote, El Salvador, December 2001.

El Mozote villagers and relatives of the victims during a vigil and reburial ceremony at the local church. It is hoped that the findings of the investigation will help clarify the historical record concerning one of the most debated and contested events in recent Salvadoran history. Also, the training of the professionals from the Institute of Legal Medicine and the introduction of forensic anthropological methodology into the Salvadoran justice system provide new tools to uphold the rule of law in El Salvador.

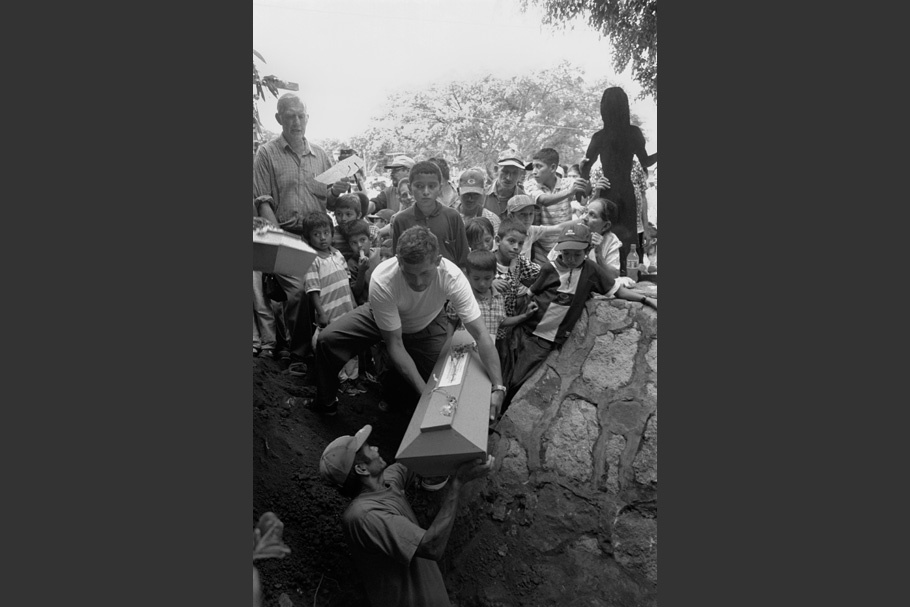

20030130-linger-gasiglia-mw07-collection-020

El Mozote, El Salvador, December 2001.

Members of the El Mozote community deposit coffins inside the village’s monument. This monument, a metal sculpture of a family holding hands, already contains most of the remains of 141 people exhumed in 1992, 34 people exhumed in 2000 and 40 people exhumed in 2001.

Pedro Linger-Gasiglia is a freelance photographer based in New York City. Born in Argentina, and raised in Brazil, Bolivia, Costa Rica and Nicaragua, he is fluent in Portuguese, Spanish, and French. His work has been featured in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Mother Jones, Clarín, and La Nación. He has participated in exhibits in the United States and throughout Latin America. He received a BFA from New York University and an award for “Continuous Excellency in Documentary Photography.”

Since 1997, through an initial grant from Andean University and in collaboration with the United Farm Workers, Gasiglia has been documenting Latin American immigrant communities in the United States. He has been working with juvenile detainees in Nicaragua during the implementation of a reform intended to empower local judicial courts and police. Since 1998 he has collaborated with the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF). During 2001 and 2002, he traveled to El Salvador to document their work in conjunction with local human rights organizations to recover and identify victims of the Salvadoran civil war. Currently he works in New York with photographer Susan Meiselas.

Pedro Linger-Gasiglia

My collaboration with the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF) began in 1998. In 2001 and 2002 I traveled to El Salvador to document their work exhuming and identifying the victims of the El Mozote massacre. I learned first-hand that the involvement of relatives and survivors was essential to the reading of recovered bones from mass graves and the historical reconstruction of the massacre. The process of identifying the victims through forensic science and returning the remains to the families for proper burial are prerequisites for the healing of the victims and the restoration of the social order. The ordinary response to atrocities is to banish them from consciousness. But atrocities refuse to be buried.

Between the 6th and 16th of December, 1981, the Salvadoran armed forces conducted a large-scale operation in Morazán, a province in the northeastern region of the country. Over this period, they allegedly massacred approximately 800 civilians in six neighboring villages. There was no Salvadoran opposition press in the early 1980s, and information regarding the nature of military operations was controlled by the armed forces. Only one local newspaper reported on “Operation Rescue” while it was taking place. Journalists and the International Red Cross were denied access to the area. Radio Venceremos, the rebel radio station, didn’t report on the massacre until the end of December 1981.

The international community found out about the massacre on January 27, 1982, when the New York Times and the Washington Post published pictures and detailed stories from survivors. Neither the United States nor the Salvadoran government conducted a serious investigation, and the Salvadoran government refused to allow independent investigations.

Human rights groups, survivors, and relatives of the victims continued to press for a thorough investigation. In 1989, Tutela Legal (the Human Rights Legal Office of the Archbishop of San Salvador, established by the late Archbishop Oscar Romero) and local organizations from Morazán began an extensive investigation into the massacre. In 1990, Tutela Legal filed an initial brief on behalf of survivors and insisted on exhumations in the villages where the massacre took place. In 1992, shortly after the Salvadoran government and the guerrilla army signed peace agreements ending the war, Tutela Legal invited the EAAF to assist with its investigation. In the fall of 1992, under the auspices of the United Nations Truth Commission for El Salvador, EAAF exhumed a site in El Mozote and recovered the skeletons of 147 individuals, 131 of whom were children under the age of 12.

These findings were one of the principal reasons for the U.N. Truth Commission’s conclusion that the Salvadoran Army had committed a massacre in El Mozote and five nearby villages resulting in the deaths of at least 500 people and probably many more. The findings prompted the Clinton administration to publicly rectify the U.S. State Department’s position that the massacre had not occurred. Just days after the United Nations issued its report the Salvadoran legislature passed an amnesty law that barred prosecution of human rights violators. Nevertheless, relatives of the victims continued to demand further investigations and EAAF conducted more exhumations from 2000 to 2002. EAAF is preparing to continue its investigations in 2003.

I have often wondered why relatives of the victims continue to demand the exhumation of their loved ones 20 years after their deaths. There certainly isn’t only one answer. Identification of victims is a great source of relief to family members who lived through the massacre. Only after this process is finished can the people in Morazán begin to re-create a sense of community. Through these photographs I hope to convey the complexities of achieving peace in the absence of war.

—Pedro Linger-Gasiglia, January 2003