20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-001

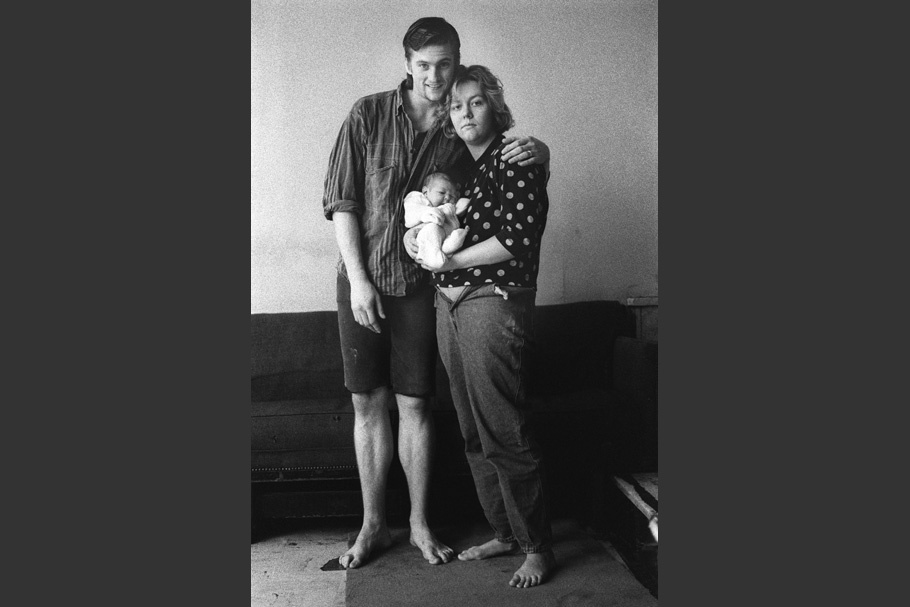

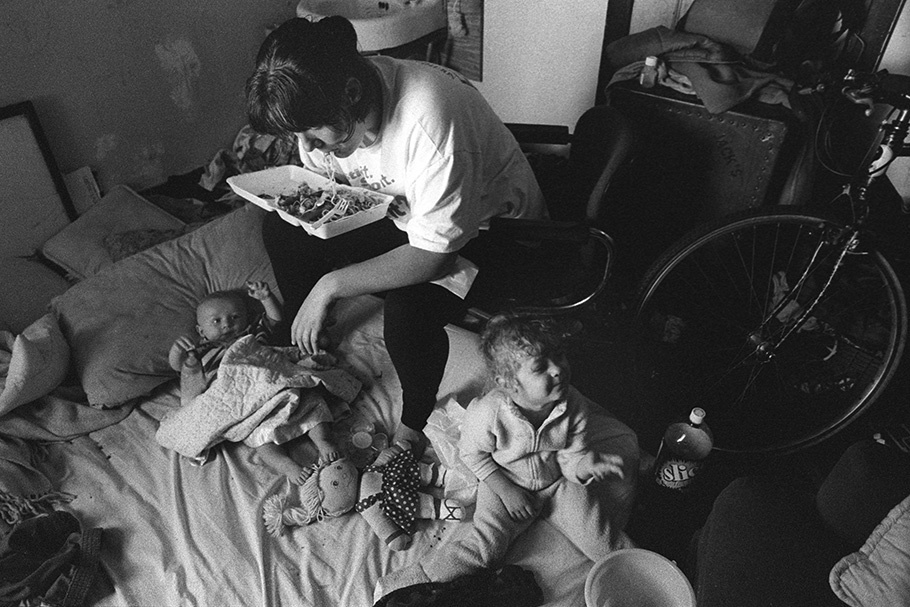

Julie and Jack with their newborn Rachel, while living at the Ambassador Hotel in a single room.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-002

Julie holds Rachel above her while lying down.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-003

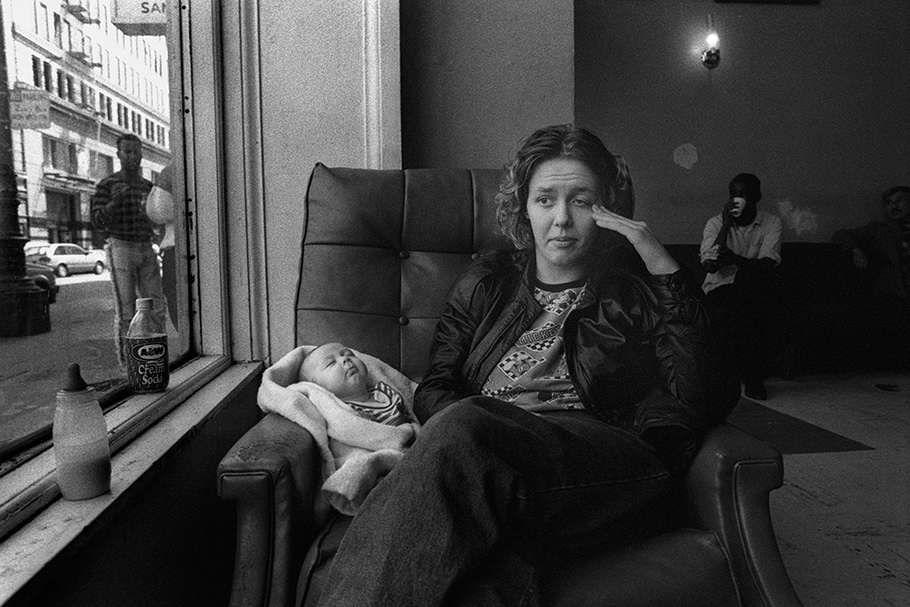

Julie sits in the lobby of the Ambassador Hotel with Rachel at three months.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-004

At the West Hotel, Julie and Rachel spend much of their time hanging out in the hallway because their room is infested with fleas.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-005

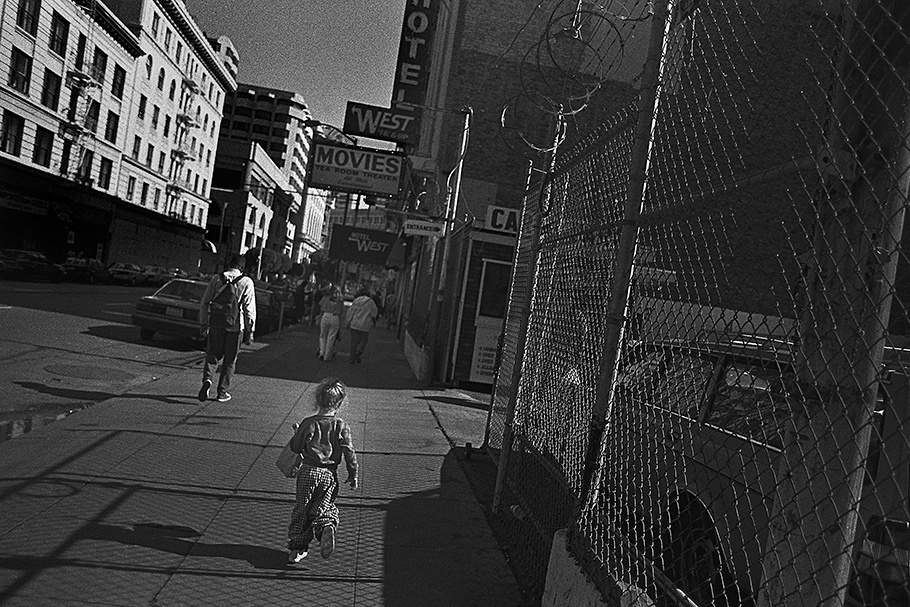

The Ambassador Hotel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin District, where Julie and Jack have lived on and off.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-006

In 1995, Julie left Jack because he was abusive. She moved to another hotel in the same neighborhood. From 1995 to 1998, Julie lived in some twenty different places and in three different cities. When she moved, Julie would leave only with what she could carry.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-007

Julie comforts Robert as he cries after hitting his head. Robert is one of the many kids living in the West Hotel, who Julie babysits for while the parents are getting high. Robert’s parents were kicked out of the hotel and did not come back for him for more than a week.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-008

Julie watches Rachel and Robert (another child in the hotel) play on the stairs at the West Hotel. This is the only place the children have to play; many hotels won’t accept children because of the liability.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-009

Julie and Rachel play with Jean and her children. Jean and Julie were friends before Jean and her family had to leave town because her husband, Harold, owed money for his drug habit. They left in the middle of the night and did not tell anyone but Julie.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-010

Julie hugs Rachel after a long day.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-011

Julie sits with Rachel on the stairs at the Hillsdale Hotel. She is seven months pregnant from Steven, who wants nothing to do with Julie or the baby. Julie does not believe in abortion.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-012

Julie and Rachel leaving the West Hotel. After Julie and Jack broke up in 1994, she drifted from one residential hotel to the next, taking little with her but Rachel. In one year, she moved 12 times.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-013

Rachel runs to catch up with Julie as they walk back to the hotel.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-014

After their baby Jordan was born, Julie and Jason kidnapped her from the hospital because Julie feared her baby would test positive for drugs and be taken from her. When the police caught up with Julie, she lost custody of her daughter, and was given a year in county jail. Jason and Julie were released after six months. In March of this year, Jason and Julie had baby named Ryan, who is also in protective custody. Both Julie and Jason are in drug rehabilitation programs, which is the only way they can get their children back.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-015

Tommy is two months old and Julie has still not received an increase on her welfare grant because she had not provided a birth certificate. She tells me she had not been able to afford one, so I go with her and purchase the $11 dollar certificate.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-016

Julie either eats take-out food, eats at a soup kitchen, or sometimes borrows a hot plate because she doesn’t have a kitchen to feed her family.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-017

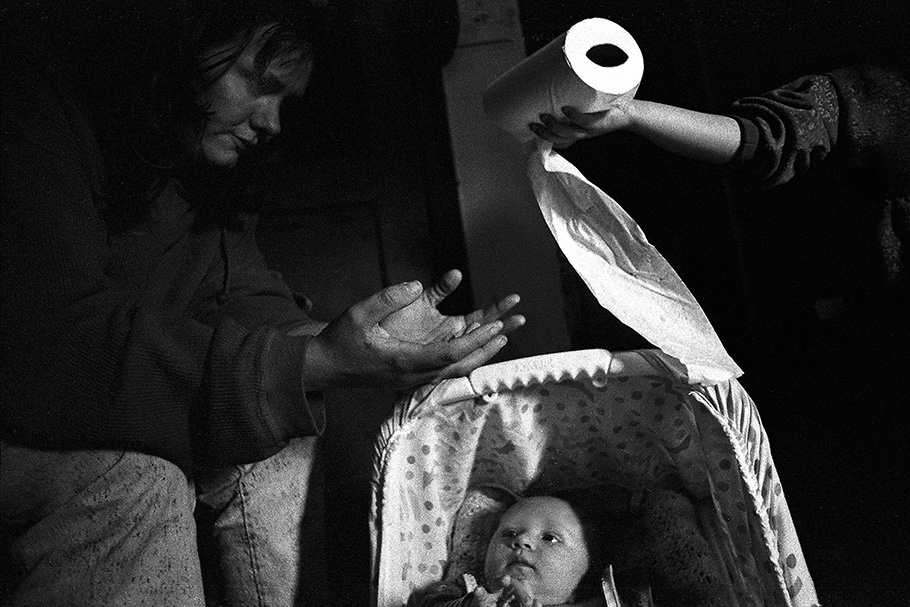

Rachel hands Julie some toilet paper. She is very sick and ends up in the hospital because of her asthma.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-018

Jack helps Julie, Rachel, and Tommy as they move into a live-in program at the Salvation Army. They live in an apartment with a kitchen and their own bathroom. Julie is attending parenting classes and gets drug counseling. Rachel and Tommy go to day care.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-019

Jason, who is Julie’s current boyfriend and father of two of her children, stands outside their room and smokes in a trash well. Jason has AIDS.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-020

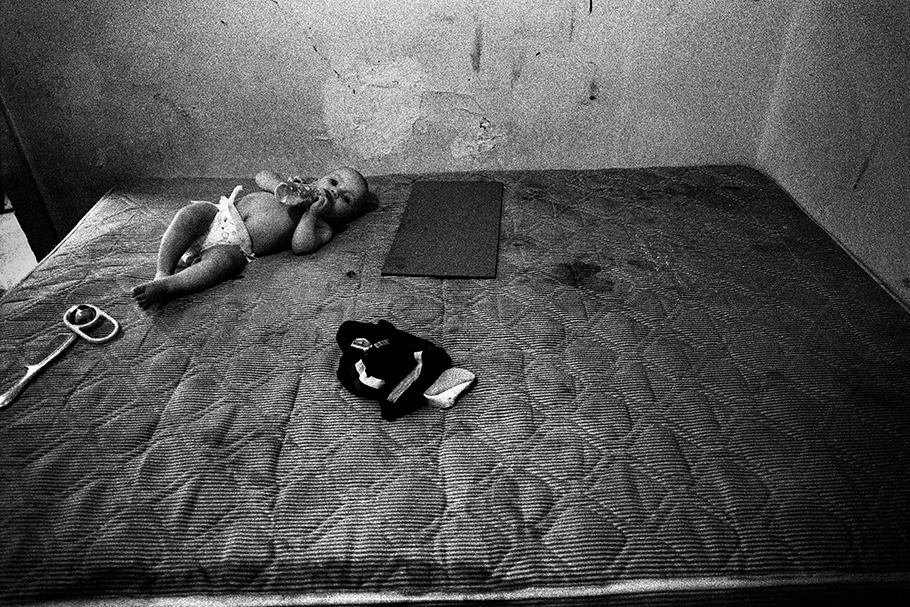

Julie, Rachel, and Tommy at the Hillsdale Hotel in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. They share a communal bathroom. Julie is afraid to leave her kids alone when she has to use the toilet in the night. She fears that a crack head might come in and hurt them.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-021

Julie carries Rachel who is in trouble for talking back. She is punished by standing in the corner.

20010606-padilla-mw05-collection-022

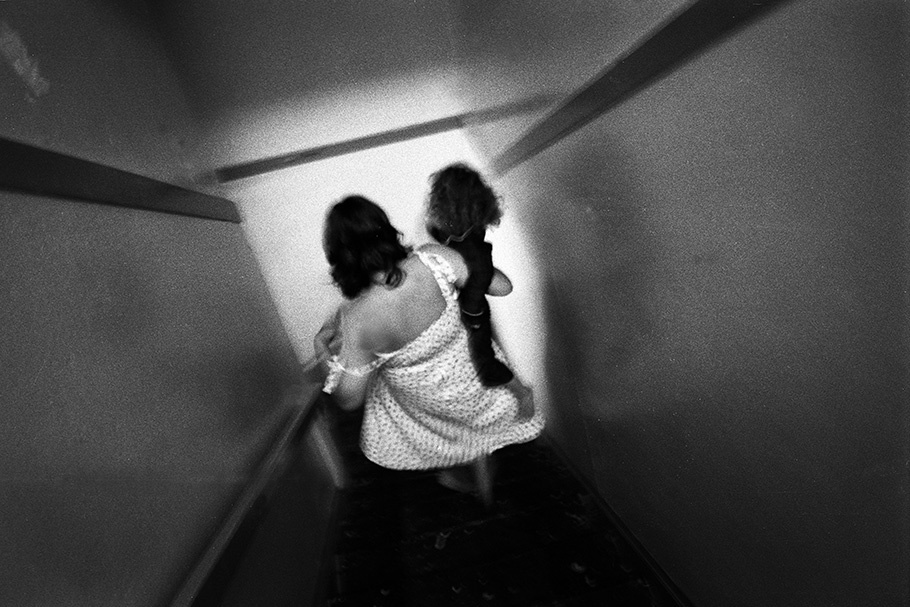

Julie and Rachel walk down the stairs at the West Hotel.

After graduating from San Francisco State University in 1991 with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism, Darcy Padilla began freelancing for the New York Times (1991 to present) and the San Jose Mercury News (1993) in between traveling to Latin America to work on documentaries. Since then she has worked on a nine-year project chronicling the lives of the urban poor. Padilla’s work has appeared in many publications, including the New York Times, the Washington Post, Life, Fortune, Harper’s Bazaar, and Graphis. The United Nations selected her project on Urban Poverty for the UNAIDS exhibition in Geneva in 1997. She participated in an exhibition of Latin American photographers entitled Centro De La Imagen, which exhibited 96 photographers of Latin descent and traveled to five different countries over two years in 1996 and, in 1990, received the Alexia Foundation Award for world peace and understanding. Padilla was also awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 1995 and an Open Society Individual Project Fellowship in 1998.

Darcy Padilla

Poverty, AIDS, drug abuse, emotional, and physical abuse, and strained and sundered relationships with friends and family—the problems that plague people who belong to our society’s underclass are tangled and tied together like a Gordian knot. America may be the most open society in the world, but for many, its promise cannot overcome the grim reality of living with these problems in places like San Francisco’s Tenderloin.

Julie Baird is one of these people. Julie has been on her own since her sexually abusive stepfather threw her through a glass window when she was 14 years old. She ran away from home, lived on the street, used drugs, picked up HIV, and had four children (Rachel, Tommy, Jordan, and Ryan).

When I first met Julie in February 1993 in the lobby of a single room occupancy hotel, she was 18 years old and had just given birth to her first child, Rachel. Julie and Jack Fyffe, the 19 year-old father, were both HIV positive. Rachel, they said, was their main reason for living. Over the last eight years, I have photographed Julie’s struggle to stay off drugs and her innumerable moves from one dilapidated residential hotel to another.

Julie’s story is a complex one of multiple homes, AIDS, abusive relationships, drug abuse, and poverty. A victim of child abuse, Julie often neglected her own children. A high school dropout, she depends on welfare to feed her family. HIV positive, she fights to stay off drugs. Fyffe, Rahcel’s father, was an addict who died of AIDS in March 1998. Jason Dunn also has AIDS, is the father of her two youngest children, and served time in jail, as has Julie. All of Julie’s children are now in foster care.

Julie’s problems are too tightly woven to be resolved by a single remedy, whether drug rehabilitation, job training, or workfare. Her experiences remind us that there are no simple solutions to our complicated and ever-changing public health problems. If we are to understand why our drug policy, health care system, and responses to AIDS and poverty are failing, we must first understand the nature of Julie Baird’s life.

—Darcy Padilla, June 2001