20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-001

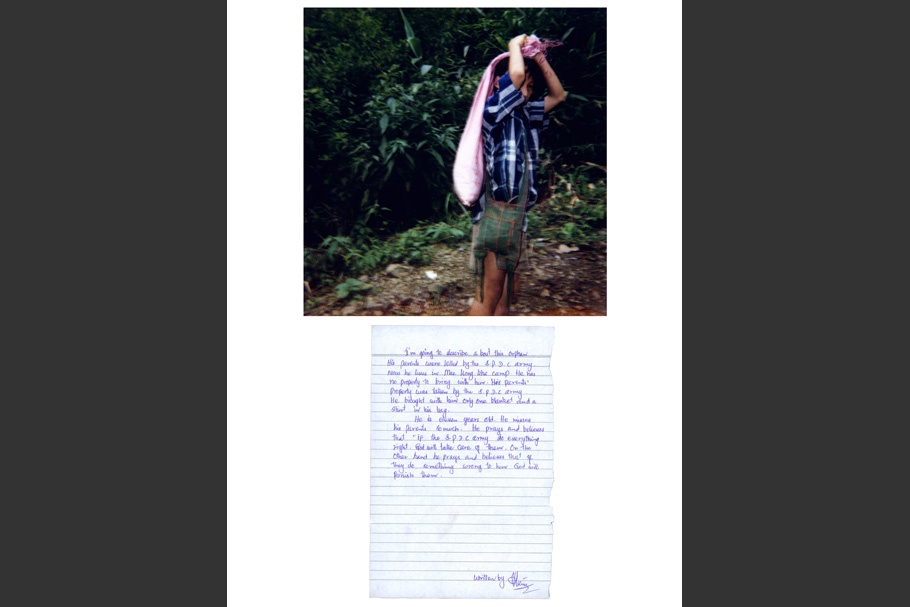

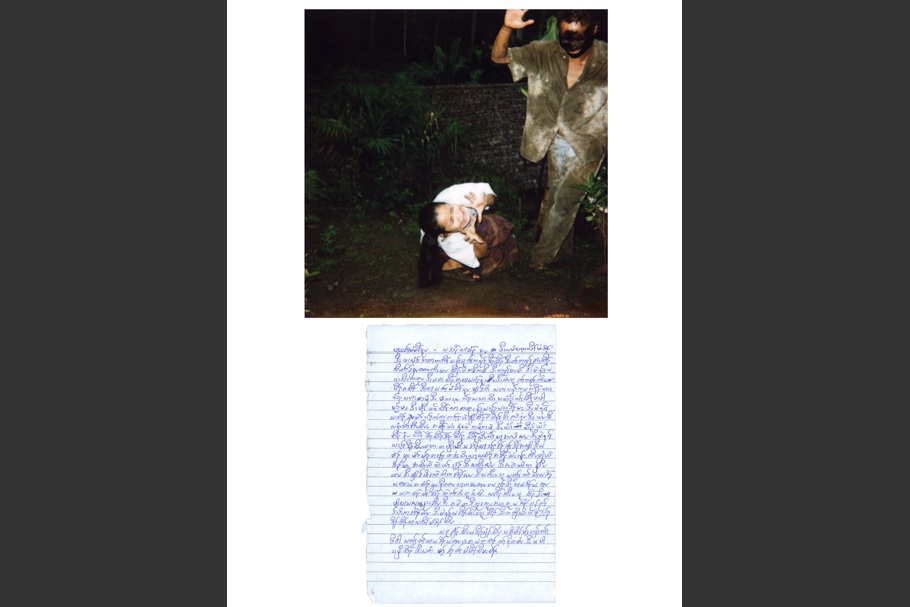

Naw Sah Rie Doh

I’m going to describe about this orphan. His parents were killed by the S.P.D.C. army. Now he lives in Mae Kong Kha camp. He has no property to bring with him. His parents’ property was taken by the S.P.D.C. army. He brought with him only one blanket and a shirt in his bag.

He is eleven years old. He misses his parents so much. He prays and believes that “if the S.P.D.C. army does everything right, God will take care of them. On the other hand he prays and believes that if they do something wrong to him, God will punish them.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-002

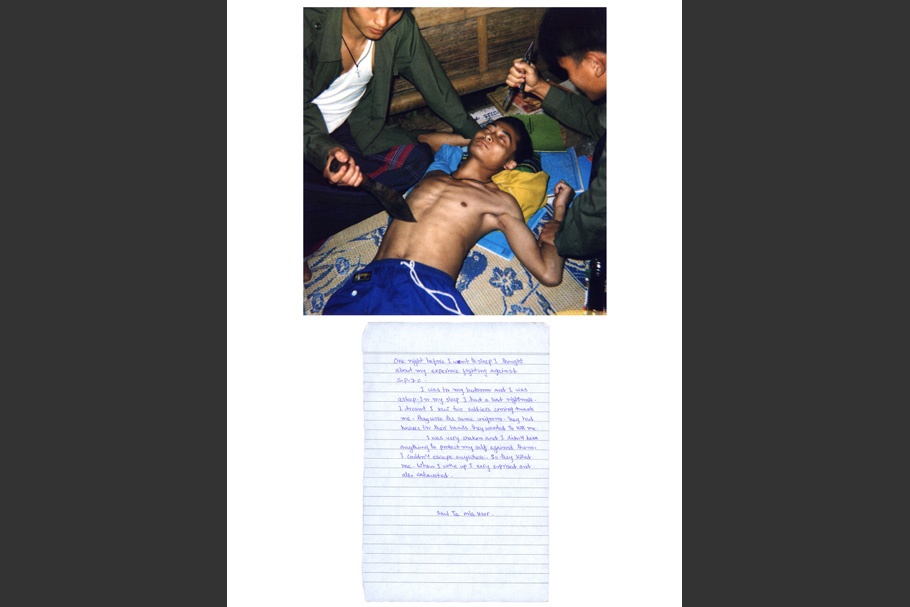

Saw Ta Mla Hser

One night before I went to sleep, I thought about my experience fighting against S.P.D.C.

I was in my bedroom and I was asleep. In my sleep I had a bad nightmare. I dreamt I saw two soldiers coming towards me. They wore the same uniform. They had knives in their hands. They wanted to kill me.

I was very shaken and I didn’t have anything to protect myself against them. I couldn’t escape anywhere. So they killed me. When I woke up, I very surprised and also exhausted.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-003

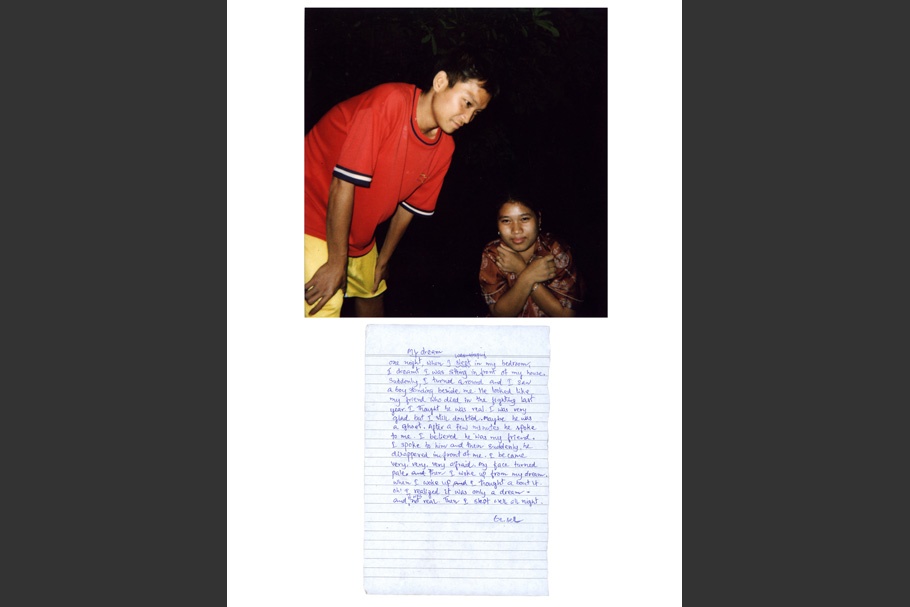

Naw Christian Po

My Dream

One night when I slept in my bedroom, I dreamt I was sitting in front of my house. Suddenly, I turned around and I saw a boy standing beside me. He looked like my friend who died in the fighting last year. I thought he was real. I was very glad but I still doubted. Maybe he was a ghost. After a few minutes he spoke to me. I believed he was my friend. I spoke to him and then suddenly, he disappeared in front of me. I became very, very, very afraid. My face turned pale. Then I woke up from my dream. When I woke up, I thought about it. Oh! I realized it was only a dream and it was not real. Then I slept well all night.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-004

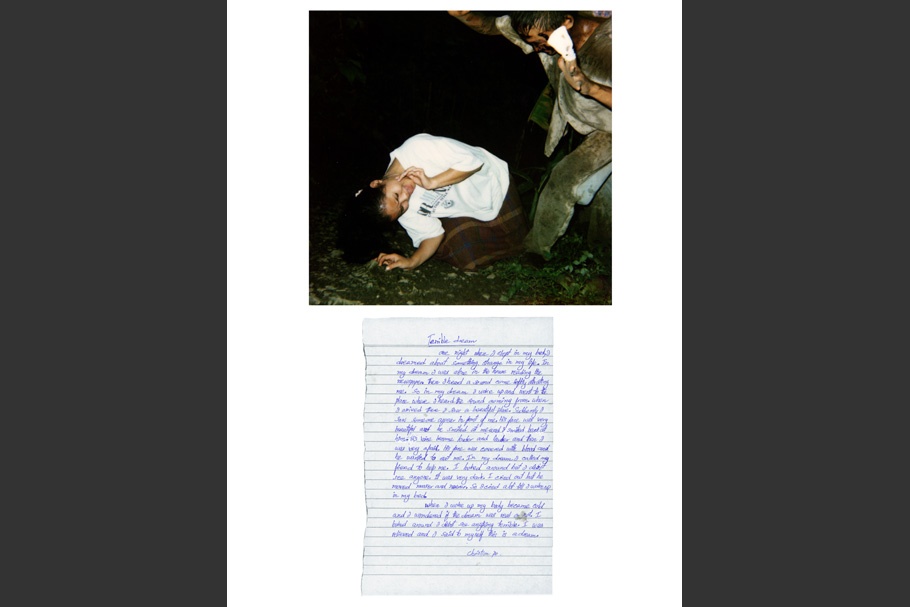

Naw Beselda

Terrible Dream

One night when I slept in my bed, I dreamed about something strange in my life. In my dream I was alone in the house reading the newspaper. Then I heard a sound come softly attracting me. So in my dream I woke up and went to the place where I heard the sound coming from. When I arrived there I saw someone appear in front of me. His face was very beautiful and he smiled at me and I smiled back at him. His voice became louder and louder and then I was very afraid. His face was covered with blood and he wanted to eat me. In my dreams I called my friend to help me. I looked around but I didn’t see anyone. It was very dark. I cried out but he moved nearer and nearer. So I cried a lot till I woke up in my bed.

When I woke up my body became cold and I wondered if the dream was real or not. I looked around. I didn’t see anything terrible. I was relieved and I said to myself this is a dream.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-005

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-006

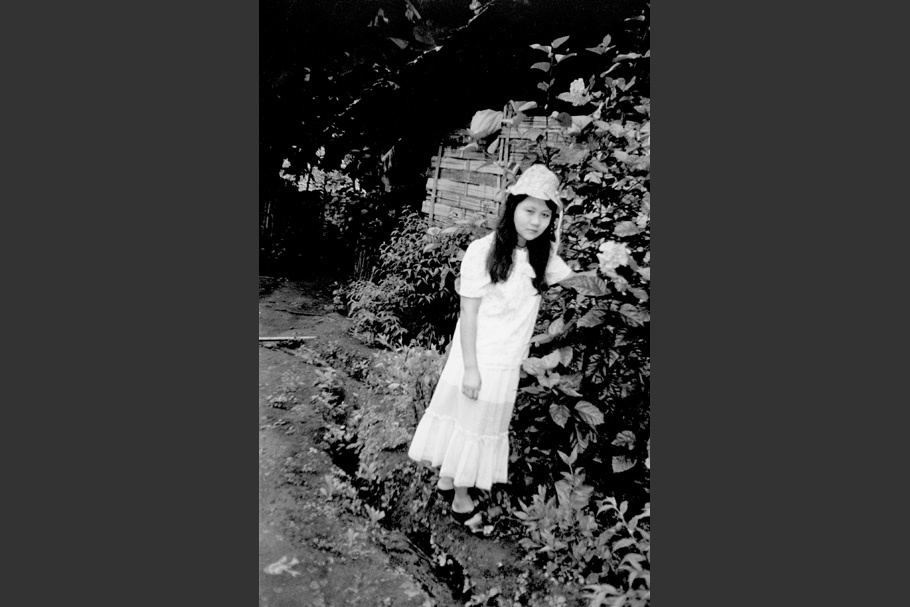

Naw Moo Nu

I dreamt I went to the Karen New Year's celebration,

so I was dressed in Karen traditional clothes as I went to the festival.

I was very happy because my friends went with me.

I was standing, and they took a picture.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-007

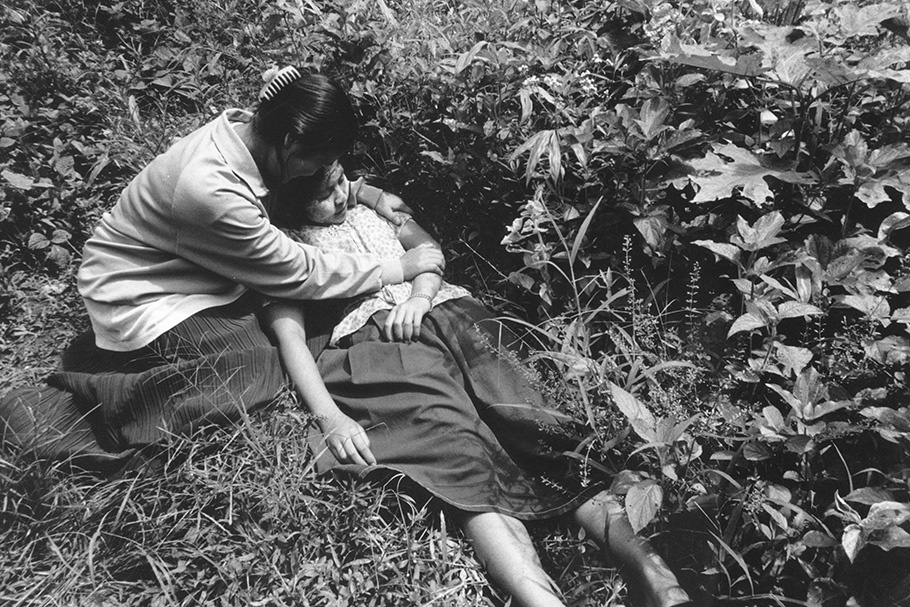

Naw Ann Eh Poh

I made a new friend, and we talked.

When I'm sitting down with my friend on the stone, I see nature.

This makes our minds very happy.

When I got up in the morning, I went back to the place where me and my friend had been.

I was looking for her but I didn't see her.

So I was searching for her everywhere.

While I was searching for her, I spotted her from a distance.

I looked at her, then I realized she was already dead.

And then I ran toward her, hugged her, and I cried with deep sorrow in my heart.

I remember the time we were together when we were walking, talking with happiness.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-008

Naw Ann Eh Poh

I made a new friend, and we talked.

When I'm sitting down with my friend on the stone, I see nature.

This makes our minds very happy.

When I got up in the morning, I went back to the place where me and my friend had been.

I was looking for her but I didn't see her.

So I was searching for her everywhere.

While I was searching for her, I spotted her from a distance.

I looked at her, then I realized she was already dead.

And then I ran toward her, hugged her, and I cried with deep sorrow in my heart.

I remember the time we were together when we were walking, talking with happiness.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-009

Naw Ta Kaw Paw

When I was eating, Burmese soldiers came so I had to run,

and I could only take a cooking pot, basket and a plate of rice.

I had to leave everything else behind.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-010

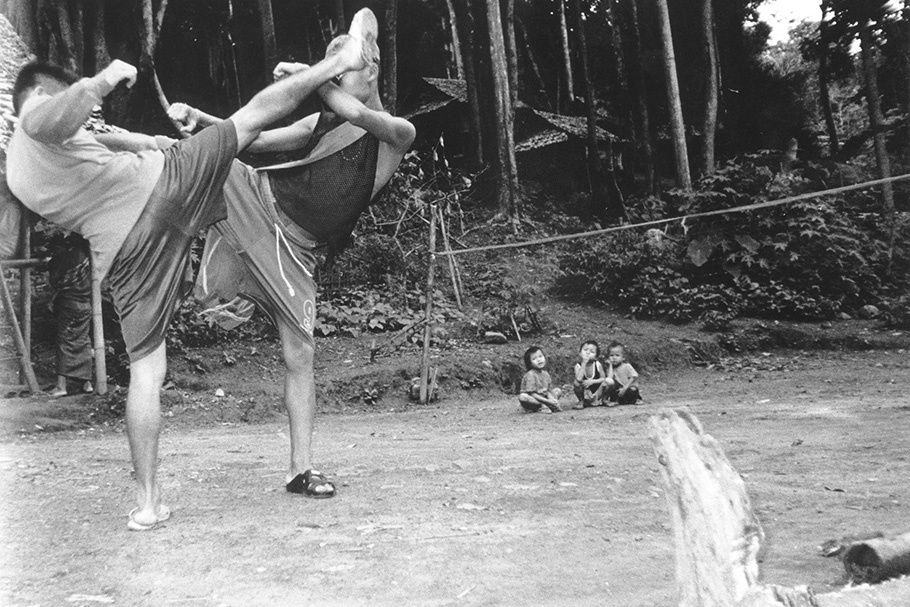

Saw Plow Htoo

When I sleep, I am dreaming.

I dreamed I went to school and I saw someone.

He hit me and I kicked him back. I kicked him and he blocked and hit me.

He held my head and hit me with his knee.

Then I fell and he kicked me, and I kicked him back.

And then I went to school.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-011

Saw Plow Htoo

When I sleep, I am dreaming.

I dreamed I went to school and I saw someone.

He hit me and I kicked him back. I kicked him and he blocked and hit me.

He held my head and hit me with his knee.

Then I fell and he kicked me, and I kicked him back.

And then I went to school.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-012

![Naw Paw Poh. We left our home and land because Payaw [Burmese government soldiers] oppress us. Payaw always approach from one place up to another. The Burmese soldiers chase us and we run away. Photo credit: © Dwayne Dixon Two boys with guns.](../../sites/default/files/styles/mw_collection_910/public/photos/20010606-dixon-mw05-012-910.jpg%3Fitok=lopJh7lS)

Naw Paw Poh

We left our home and land because Payaw [Burmese government soldiers] oppress us.

Payaw always approach from one place up to another.

The Burmese soldiers chase us and we run away.

20010606-dixon-mw05-collection-013

![Naw Paw Poh. We left our home and land because Payaw [Burmese government soldiers] oppress us. Payaw always approach from one place up to another. The Burmese soldiers chase us and we run away. Photo credit: © Dwayne Dixon Houses in a river landscape.](../../sites/default/files/styles/mw_collection_910/public/photos/20010606-dixon-mw05-013-910.jpg%3Fitok=QyUr2E4V)

Naw Paw Poh

We left our home and land because Payaw [Burmese government soldiers] oppress us.

Payaw always approach from one place up to another.

The Burmese soldiers chase us and we run away.

The son of a career army officer, Dwayne Dixon was born in Stuttgart, Germany. While studying printmaking and painting at Trenton State College in New Jersey, he began combining radical politics with his art, becoming active within the international punk underground and self-publishing a zine entitled Astronaut Etiquette. For two years following college, Dixon lived and taught in a rural town in northern Japan and traveled extensively throughout Asia. Currently, he coordinates the “Literacy Through Photography” project, directed by photographer Wendy Ewald, at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. Through his work, he combines activism and art, advocating radical change through education and collaborative art-making.

Dwayne Dixon

Throughout my collaborative work with children, I have been intrigued by the complicated yet clear narratives they create in describing themselves, their families, their places, and their dreams. Making and describing photographs is a powerful means for children to represent themselves and challenge the ways adults see them. For children in places such as South East Asia, it is also a way to reassert their identity in times of conflict and dislocation.

In August 2000, I began working with Karen teenagers who, having fled repression and violence in Burma, were living in Mae Kong Kah, a refugee camp of 14,000 people in the Thai jungle.

We talked about how they had arrived at the camp. I asked them to think about ways they could tell about their journeys with words and drawings, and then to think of ways they could make photographs of past events. They asked questions: “How can I make photographs of my own story when I am taking the pictures?” “Is it OK if the jungle here doesn’t look like it did back home?” “What if members of my family aren’t alive anymore?” Together we devised solutions. I asked them if pictures were a kind of “language” we could “read,” and, if so, do we all read them the same way? They quickly saw that they could use pictures to tell a story from the past by recreating symbols that were evocative of an experience. Then I asked about their dreams, and having tackled the notion of dramatizing an actual past event, the students were comfortable relating dreams and making them “real” in photographs.

As the project progressed, the translators, Naw Ken, Naw Say Moo Paw, and Naw Shar Lar Wah, became the primary collaborators of the students. These women quickly learned the rudiments of photography and, together with the teachers and principal, helped the students refine their writing. Having made their own photographs, they talked with the students about their different experiences, becoming teachers themselves as they guided and encouraged the students. The experiences of these three women are part of the multiple layers of connection that the project engendered throughout the camp’s social and educational structures.

While this project began with my own questions of how we see each other and respond to the historical contexts and changes in which we live, the images and writings of the Karen students represented their essential understanding of their culture through their own perspectives and memories. Shadowed by the definitions of themselves as refugees, and backlit by an epic but largely unnoticed war for freedom from brutal repression, these young people reveal a culturally complex world created and inhabited by individuals strong in their remembering, and eloquent in their lives.

—Dwayne Dixon, June 2001