20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-001

Girl proudly shows a sculpture made out of clay. She was amputated by rebels from the Revolutionary United Front (RUF).

Freetown, April 1999.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-002

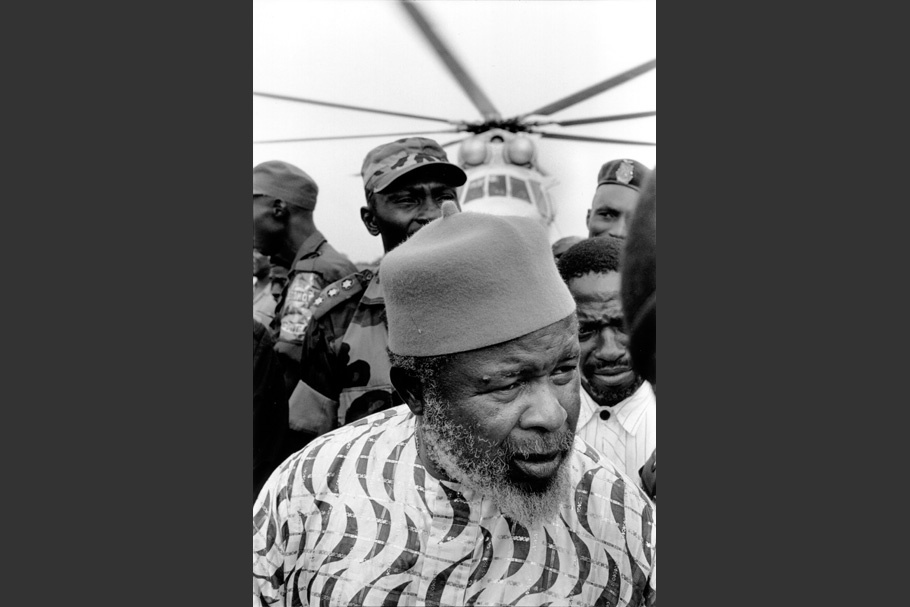

RUF leader Foday Sankoh is escorted by forces of the West African peace force ECOMOG to a rebel camp near Freetown to talk his men into disarming.

Port Loko, December 1999.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-003

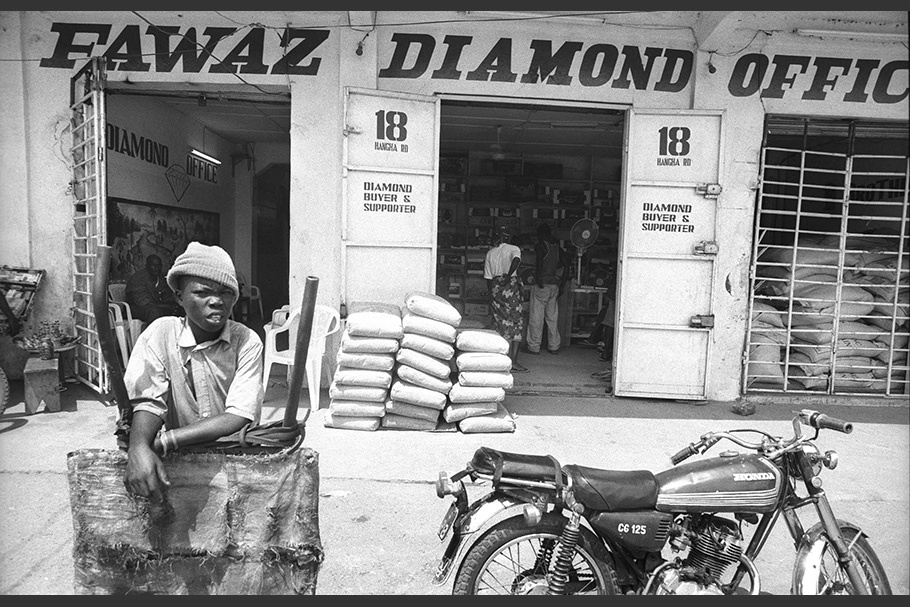

The mainstreet of Kenema, lined with diamond shops.

Kenema, May 2000.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-004

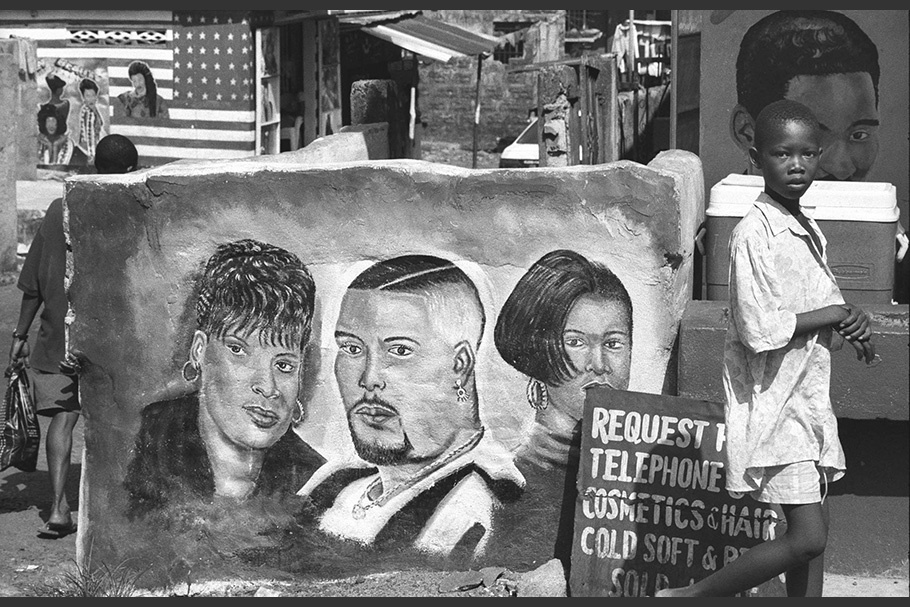

Boy walking in front of beauty parlor/hair dressing salon.

Freetown, May 2000.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-005

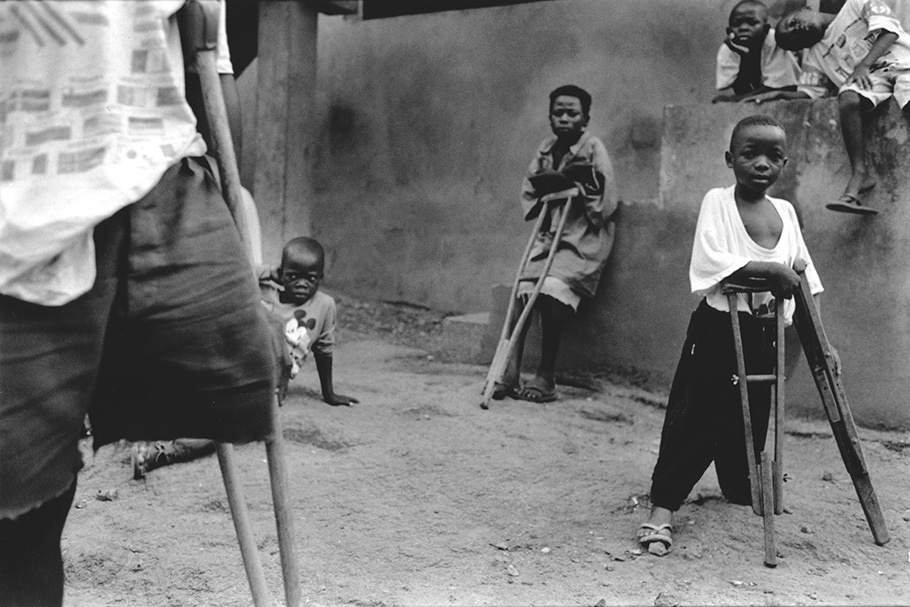

Kids at a shelter waiting for family reunification. Some were amputated by rebels, others were wounded in the war.

Freetown, December 1999.

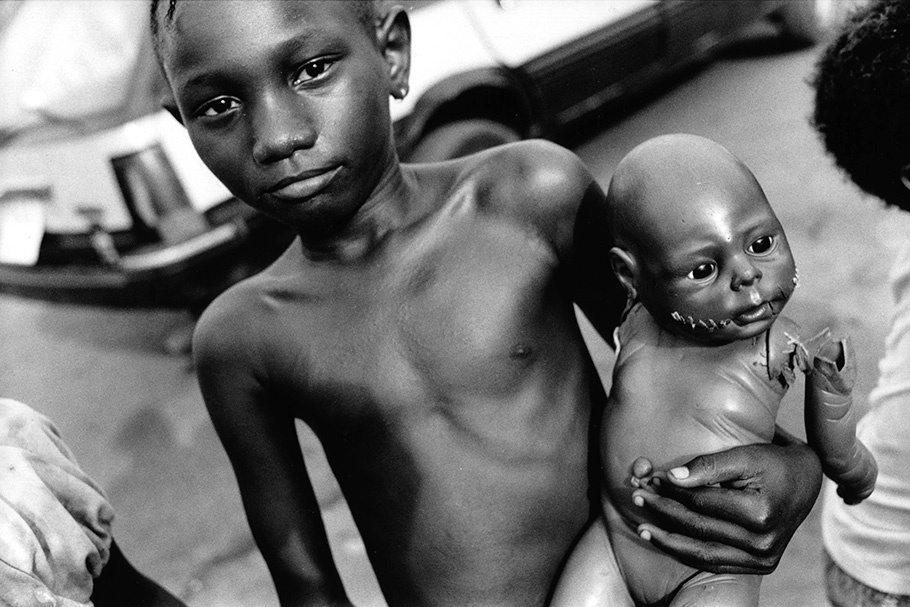

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-006

Girl with her favorite doll.

Freetown, May 2000.

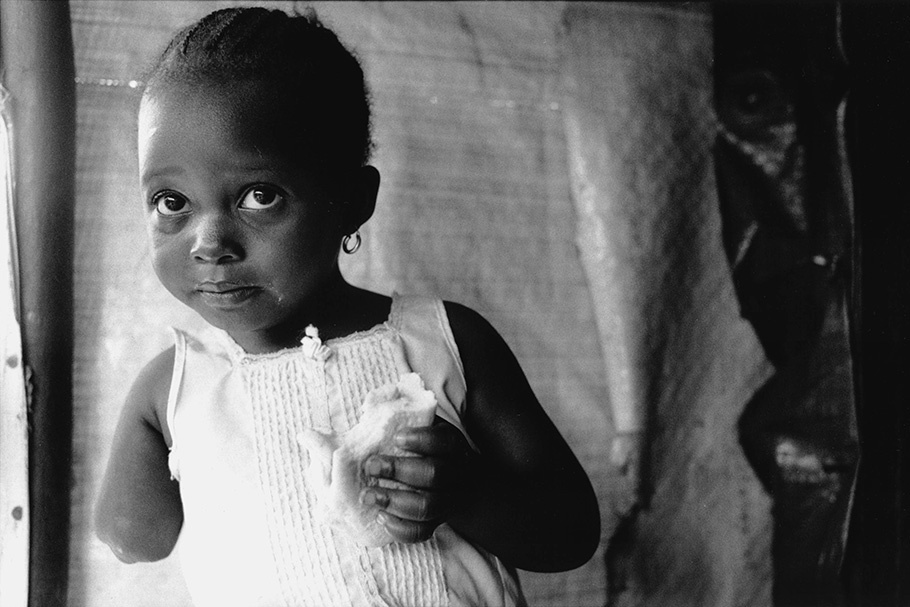

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-007

Three year old Memuna Mansarah was amputated by rebels.

Freetown, April 1999.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-008

Playing soccer at the beach.

Freetown, May 2000.

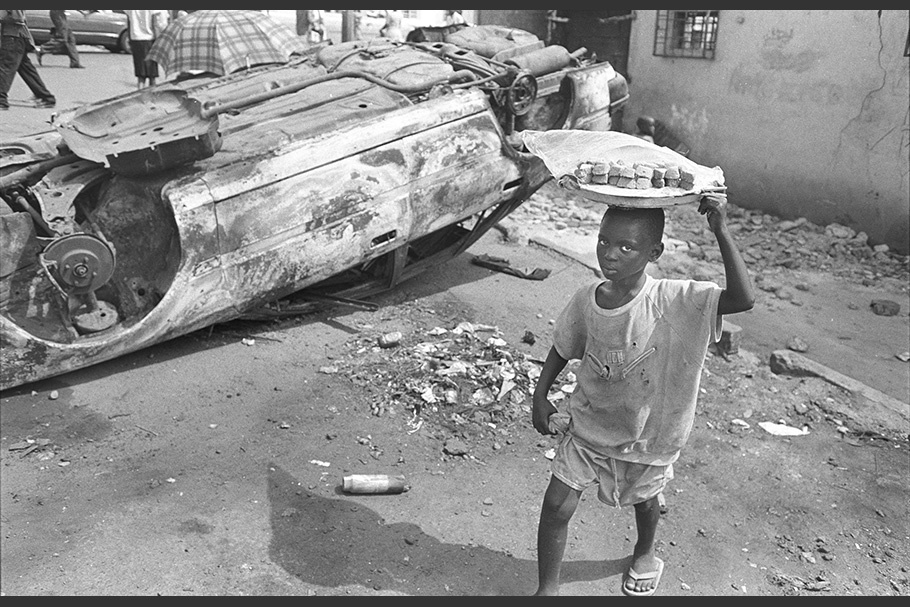

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-009

After the aborted January 1999 invasion, rebels have left a trail of destruction. Boy selling sweets among the ruins.

Freetown, April 1999.

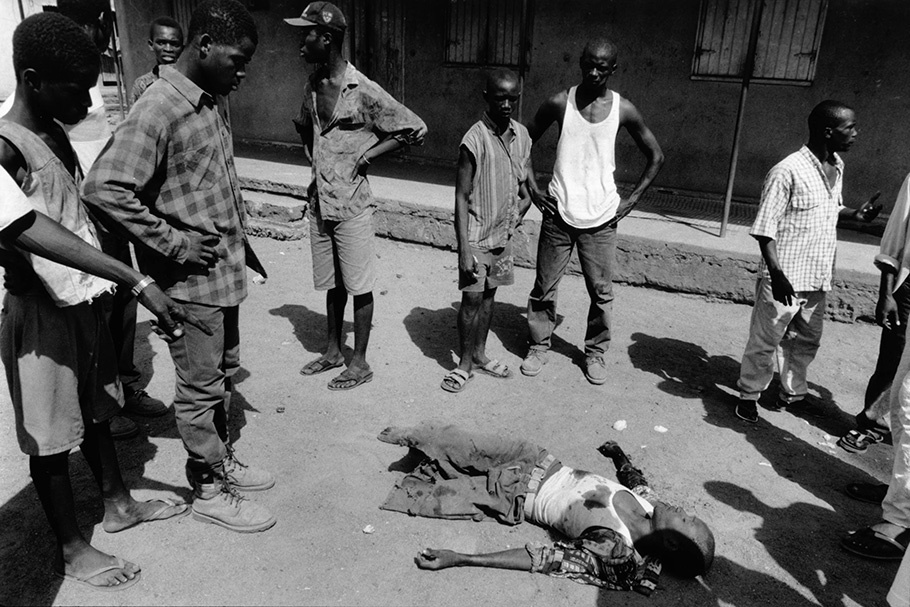

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-010

An ECOMOG jet has bombed Makeni, at that time a stronghold of the military junta and rebels. Bystanders watch a boy die.

Makeni, February 1998.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-011

An ECOMOG jet has bombed Makeni, a stronghold of both the military junta and rebels. Woman cries as she sees the destruction.

Makeni, February 1998.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-012

Thousands of people remain displaced. Older couple at a camp near Freetown.

Newton, April 1999.

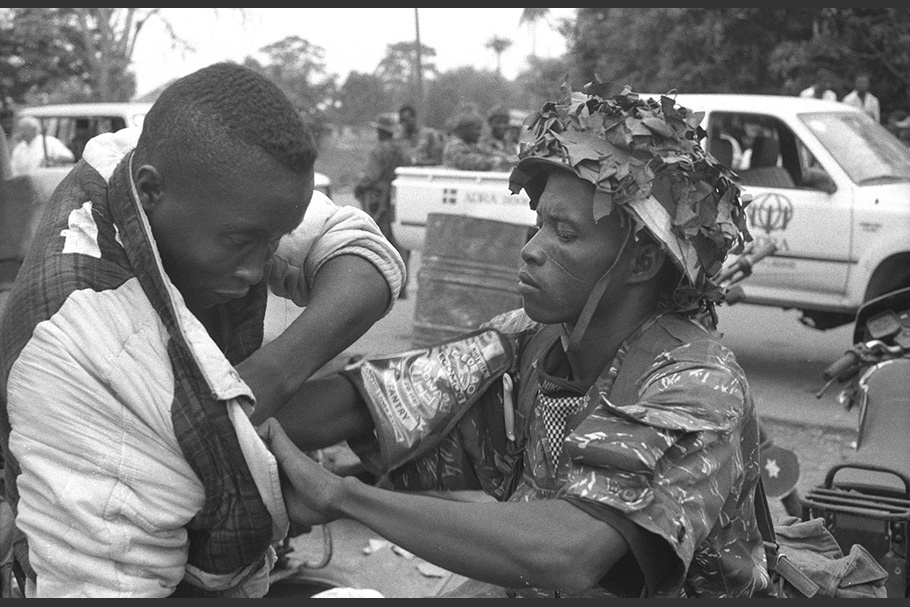

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-013

Makeni is freed from rebels and military junta. A soldier of the ECOMOG searches an arrested rebel for arms and documents.

Makeni, March 1998.

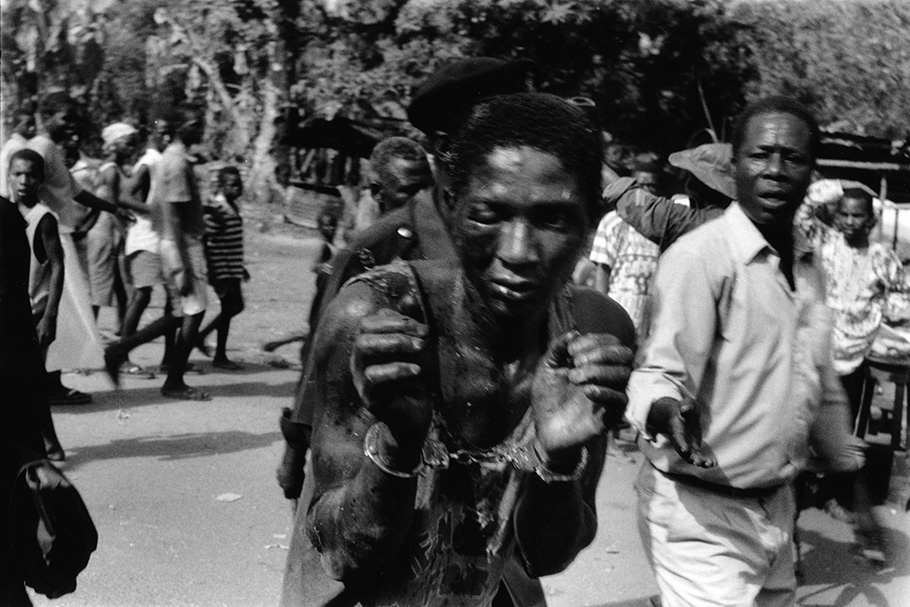

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-014

Makeni is freed from rebels and military junta. The people take revenge by molesting a suspected junta collaborator.

Makeni, March 1998.

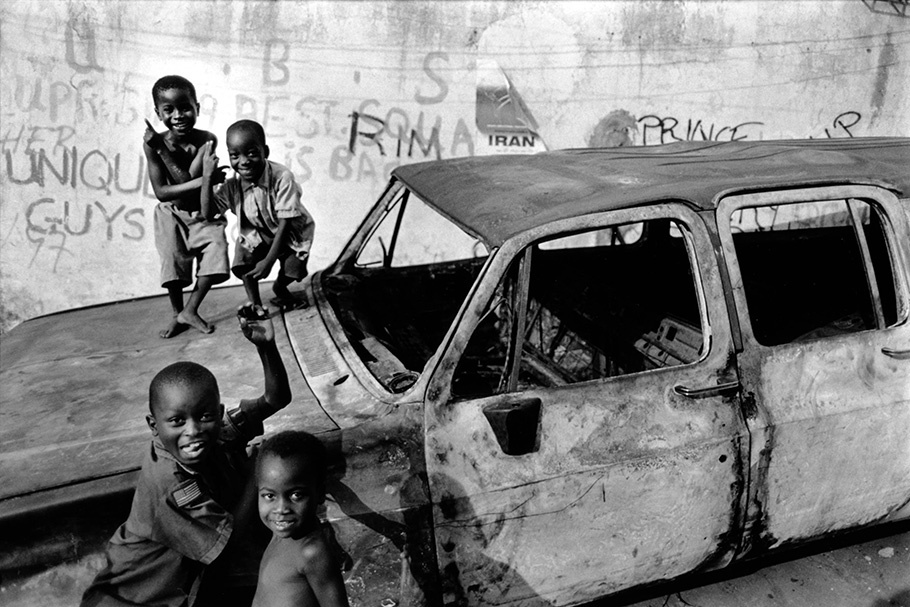

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-015

Kids playing on burnt out car wreck.

Freetown, April 1999.

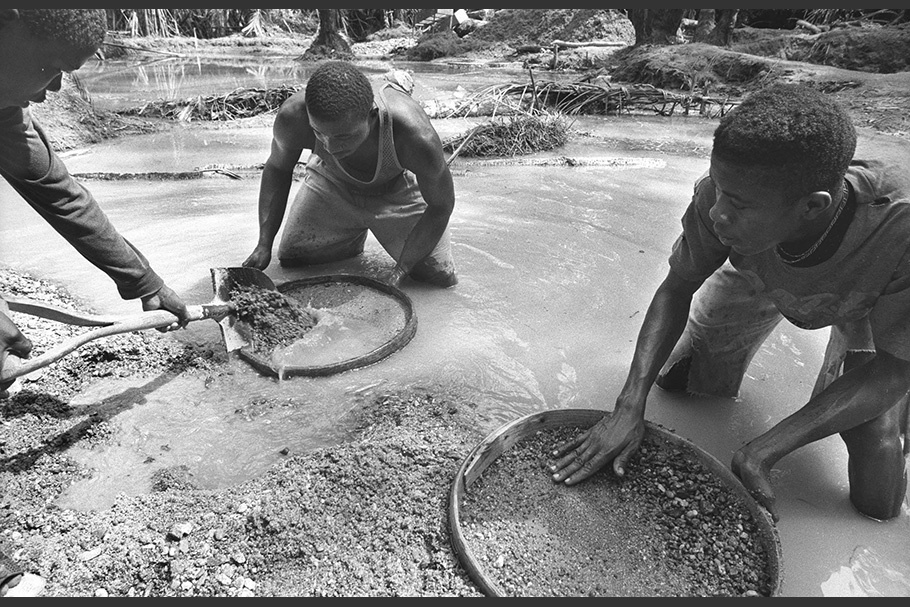

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-016

Diamond pit. Final wash of gravel that can contain diamonds.

Zimmi, May 2000.

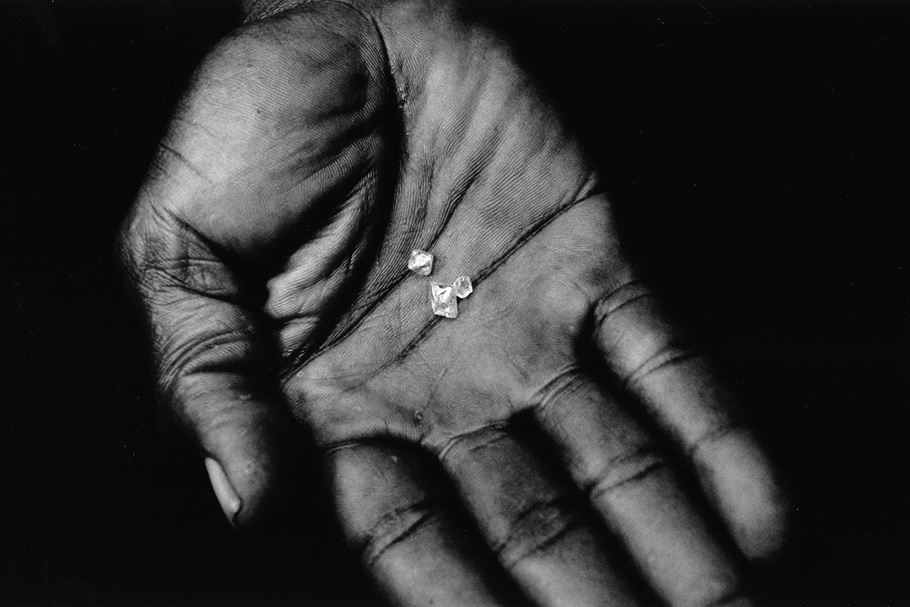

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-017

Diamond dealer showing some "stones."

Kenema, May 2000.

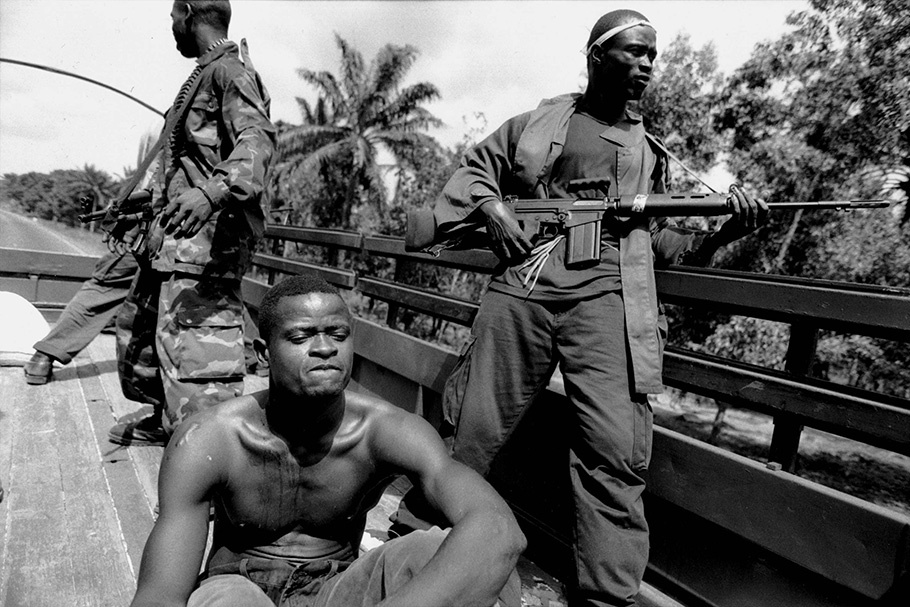

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-018

Army and Civil Defense Forces have captured a rebel and are bringing him back to Freetown.

Newton, May 2000.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-019

Government militias/Kamajors exit a pickup truck, ready to repel an expected rebel advance.

Freetown, May 2000.

20010606-voeten-mw05-collection-020

Government troops have captured a rebel. Rebel forces were close to the city, trying to invade again.

Newton, Sierra Leone, May 2000.

Teun Voeten studied cultural anthropology in the Netherlands. During his studies, which took him to Nicaragua, New York, and Ecuador, he learned photography as an assistant to several fashion and architectural photographers. After graduating in 1991, Voeten chose to work as a photojournalist, covering the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Sudan, Rwanda, Chechnya, Sierra Leone, Haïti, and Colombia. In 1996, Atlas, the Amsterdam based publishing house, published Tunnelmensen, a journalistic/anthropologic reportage about an underground homeless community living in the train tunnels of Manhattan. Voeten’s latest book, How de Body? Hope and Horror in Sierra Leone will be published by St. Martin’s Press in Spring 2002.

Voeten, who now lives in New York, has been published in Vanity Fair, the New Yorker Magazine, El Pais, Frankfuerter Allgemeine, and Granta. His photos are used by international organizations such as Doctors Without Borders, Human Rights Watch, UNHCR, and the International Red Cross.

Teun Voeten

Sierra Leone is one of the few African colonies founded on good intentions. In the 18th century, the English bought land from tribal chiefs to give liberated slaves a new home country. Since independence in 1961, coups, military dictatorship, ongoing civil war, and fraudulent elections have plagued the country. What drives the warring factions are not ideological motivations but the riches of the diamond region in the west and south of the country. In 1992, after a relatively calm period, the civil war started again with the emergence of a rebel group called the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), supported by neighboring Liberia. The RUF used terror tactics, chopping off the hands of opponents, kidnapping children to serve in their army, and burning down villages. The fighting continued on and off through 1998, the year in which the rebel leaders took over some of the most strategic cities.

In 1998 during a cease-fire, I went to Sierra Leone to do a story on child soldiers. A few days after my arrival, all hell broke loose. The military junta was brought down by ECOMOG, the West African peace force. Heavily armed men went on a rampage. Marauding rebels and soldiers nearly killed me, threatened me with torture, and then, after robbing me, let me go. For two weeks I had to hide in the bush until I could finally make it to safety. Thanks to a few brave individuals I made it back home alive. Alfred Kanu, a school principal, offered me shelter and refuge during those two terrifying weeks. Local BBC stringer Eddie Smith escorted me on a gruesome 80-mile trip over jungle tracks back to safety. To encounter such tremendous generosity and courage in a country that Robert Kaplan called “the Devil’s Poste Restante” was a powerful experience.

Although the rebel forces commit incredible acts of cruelty, most visitors to the country are impressed with the hospitality, friendliness, and honesty of the ordinary people. I went back to Sierra Leone several times, not only to help Alfred Kanu and raise funds for his school but also because I was totally fascinated by this country where the good, the bad, and the very ugly confront each other on a daily basis. With my photographs, I hope to pay homage to the people who are struggling to survive in one of the poorest countries in the world.

—Teun Voeten, June 2001