20010606-vuco-mw05-collection-001

Water

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

November 1993.

During the siege of Sarajevo from 1992 to 1995, city water supplies were shut off. Residents needed to go a long way to fill whatever receptacles they could find with water from temporary water cisterns or natural springs. The journey was often a dangerous one.

20010606-vuco-mw05-collection-002

War’s Playground

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

March 1995.

The 18th century Alifekovac graveyard above Sarajevo offered a peaceful respite for the living and the dead.

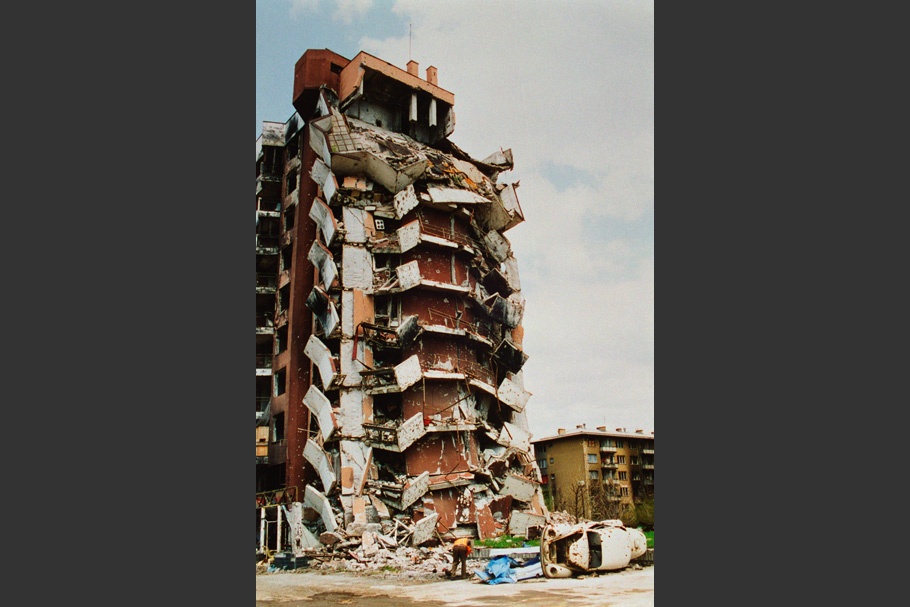

20010606-vuco-mw05-collection-003

Stove

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

March, 1996

After the signing of the Dayton Peace Accords in November 1995, Serb residents of the Sarajevo district of Grbavica began to withdraw from the capital. As they left, they destroyed, among other things, their own homes.

20010606-vuco-mw05-collection-004

Bridge

Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

August 1997.

In November 1993 a Mostar landmark—the stone bridge from the 16th century over the Neretva River—was destroyed by Bosnian Croats. The old bridge symbolized the connection between the East (Muslim) and West (Croat) sides of the city. As with the temporary bridge spanning the Neretva, those connections remain tenuous.

20010606-vuco-mw05-collection-005

Geraniums

Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

August 1997.

Mostar, due to its mild climate, is well known for its beautiful flowers. Even at the height of the conflict, Mostarians continued to decorate their windows and homes with flowers.

20010606-vuco-mw05-collection-006

The Green, Green Grass of Home

Peć, Kosovo

September 1999

During the Kosovo War in the spring of 1999, the Serbian forces destroyed the entire small, peaceful, and ethnically mixed town of Pec in the Eastern part of Kosovo. The targets were primarily family homes, mosques, bridges, and roads. The Albanian population fled the town and found refuge either in Albania or Macedonia. A majority of Albanian refugees returned to their homes later, during the summer months after the NATO intervention in Yugoslavia that ended the war in Kosovo. The Serbian and Roma population never came back to Pec, and are still, today, finding refuge in either bordering Montenegro or Serbia.

Born and raised in Yugoslavia, Beka Vučo graduated from Belgrade’s Drama and Film Academy, and, as a Fullbright scholar, completed graduate school at UCLA. She studied theater, film, and art history. In Yugoslavia, Vučo worked in the theater world, managing the avant-garde Theatre Atelje 212, and the international theater festival BITEF. After moving to New York in 1987, she worked at TIES, a theater exchange organization, and began working off-Broadway. In 1991, Vučo joined the Open Society Foundations as the regional director for Western Balkans—a position she still holds.

Vučo grew up loving the world of photography, learning from her father, Nikola Vučo, an established photographer. Her photos have been featured in books, publications, and magazines. This exhibit is taken from an ongoing project, My Balkans, 1991–2001, a photo-archival documentary about the people she has worked with, and the places she has visited in the last 10 years.

Beka Vučo

“Where are you from originally?”

“From Yugoslavia.”

“But Yugoslavia doesn’t exist any more, does it?”

“Yes, it does. When the country fell apart, its republics became the independent countries of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia. What was left is still called Yugoslavia.”

“Then what about Kosovo? It’s a part of Yugoslavia, isn’t it?”

“It is, but it really isn’t. You cannot say that.”

“Like Montenegro?”

“Sort of.”

“Ah, the Balkans! How confusing!”

For the last ten years, the Balkans have been front-page news. Until the early 1990s, Yugoslavia was known for Tito, Dubrovnik, and excellent basketball teams, but often confused with Czechoslovakia. Today, the world has learned to pronounce the difficult Slavic names and can easily find small villages and towns on the changing map of Europe—places that, previously, no one had heard of, and that no atlas carried. The world witnessed the atrocities, suffering, wars, sieges, bombed cities, mass graves, ruined and destroyed lives, and the exodus of refugees.

Even though there is still a country called Yugoslavia, that’s not the place I come from. My country is gone. The war-torn Balkans, through which I travel at least half a dozen times a year, are a different world. As the Open Society Foundations’ regional director for the Western Balkans, I went wherever there was a need, to help people and assist our local foundations in their work. Whether it was a visit to Sarajevo under siege, Kosovo after the bombing, or Belgrade during the NATO strikes, I never considered what I was doing to be either dangerous or courageous; it was part of my duty to my lost country. I had a desire to help, to share the difficult times with my colleagues, to experience a small part of what they lived, and are still living, through. And every time I boarded a plane back to New York, back to freedom, hot water, and plenty of light, my admiration grew for those people who remained. They give all of us hope and the strength to endure.

I needed to document what I saw, whom I met, where I went—people and places, the faces of history, destruction, and also hope. There was never a special assignment, but I always had plenty of film and several cameras in my bags. The photographs displayed here are part of the photo-archival documentary I am developing about my ten years of traveling through the Balkans. They are my personal, intimate view—a testament to the past and a promise for the future.

—Beka Vučo, June 2001