20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-001

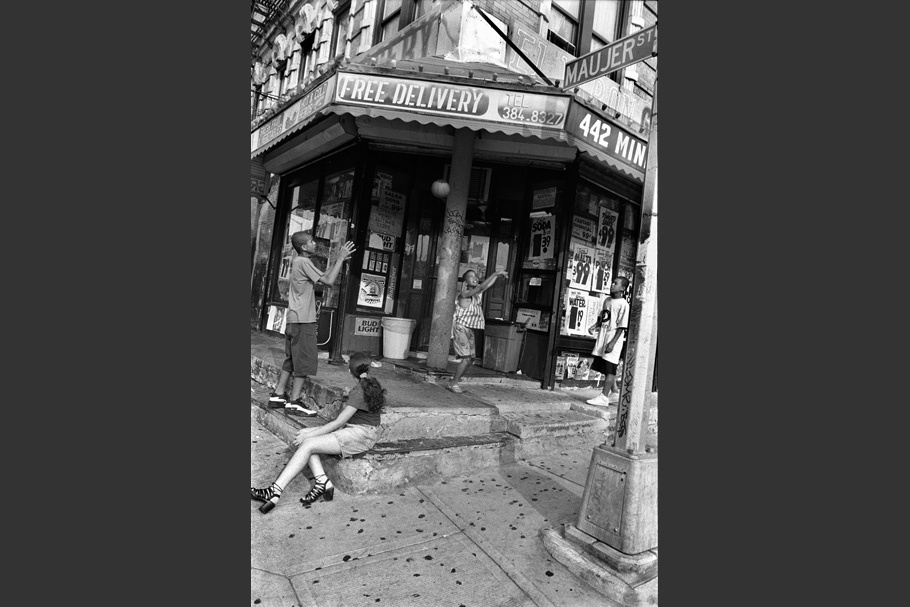

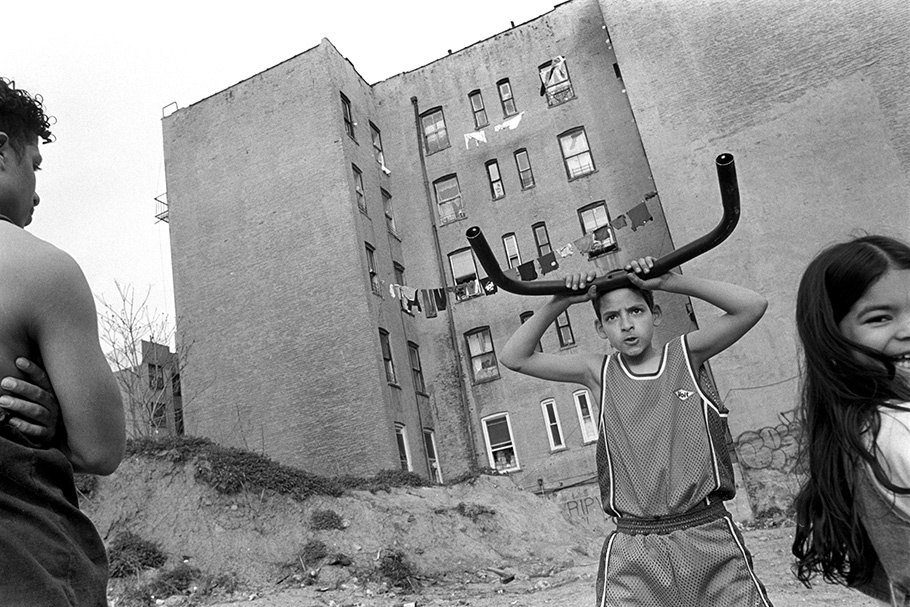

Boys playing.

Lorimer Street, 1994

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-002

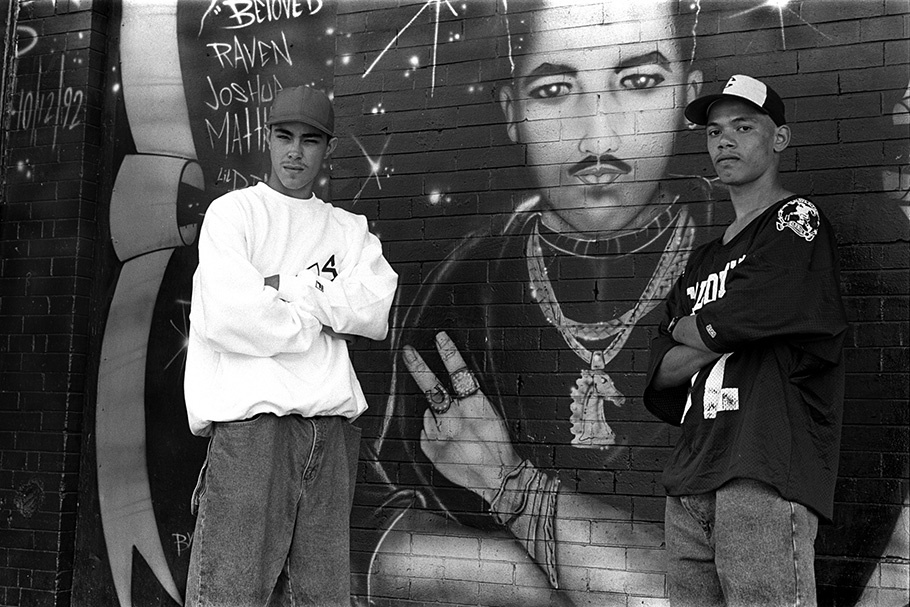

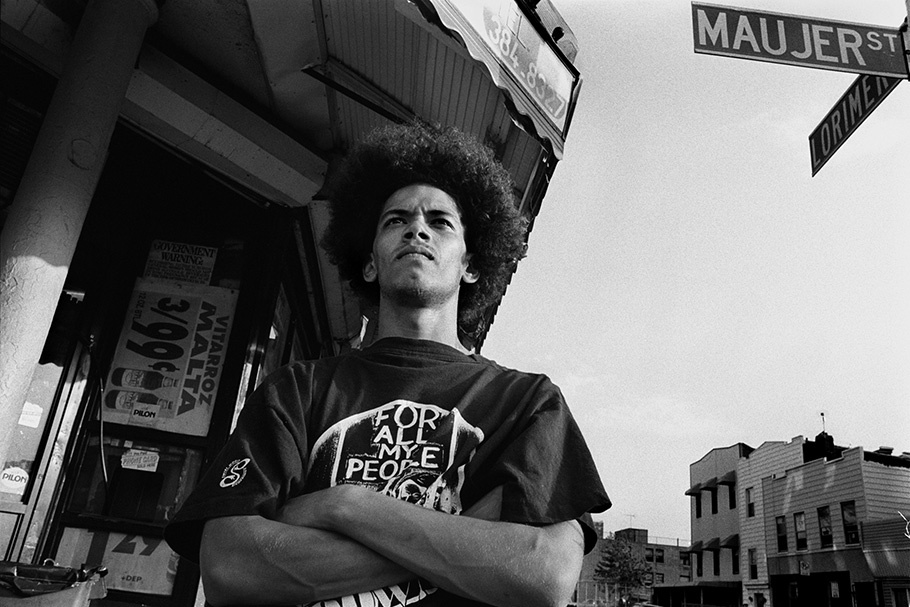

Tomar and Ricky, Maujer Boys, standing by a memorial for Benji, a Maujer Boy who was killed in 1992 at a Manhattan club while looking out for a friend.

Maujer Street, 1994

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-003

Shorty on a fence.

Lindsay Park, 1995

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-004

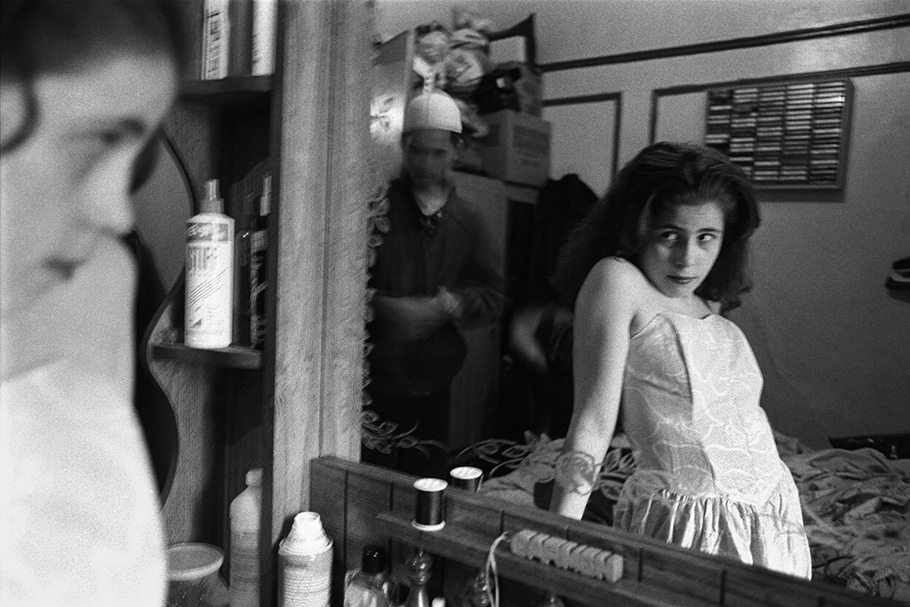

Judy, Ricky’s 11-year old sister, trying on one of her mother’s dresses.

Williamsburg, 1995

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-005

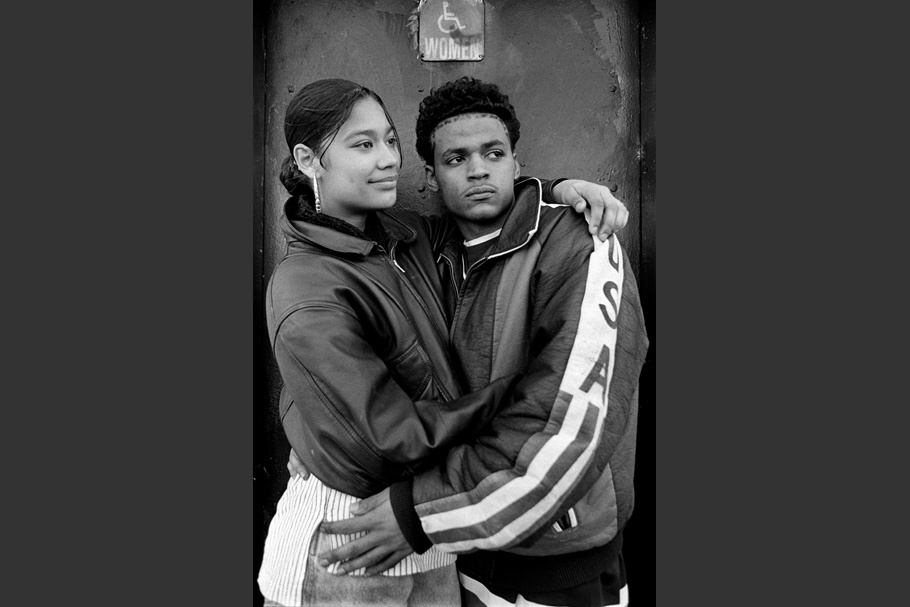

Every day Louie came on the bus from Flatbush and waited for Monica to meet him in the park. They had been going out for a few months.

Lindsay Park, 1995

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-006

The children of Maujer Street, from left: Judy, BGB, Pollo, and Woody.

Williamsburg, 1996

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-007

The playground of South Fifth Street was made of dirt and shrubs. The children called it their jungle.

South Fifth Street, 1996

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-008

Jimbo, 13-years old, with Beve.

Lindsay Park, 1997

Jimbo: Around that time, I was depressed. I felt like I had to go outside every day. I was arguing with my parents that day. I had no friends then. I didn’t know anything about anything. I just wanted to hang out and talk to these guys at the park. Things are way different now. Now I am sixteen. Maybe last year, I stopped being depressed...I started realizing what life was about: it’s not about playing games, about hanging out in the park anymore, smoking blunts every day. There are a lot of other things besides that. I think about having kids in the future, being married and living in a big house, having a nice husband, you know, having a good education. I left school when I was in eighth grade. I am gonna go to a GED program. Now, I feel that a friend is a dollar in my pocket…I have experienced hate, friendship, love. It is hard to think that you’re a grown-up, when you’re not. I know things now that some 20-year olds don’t; in a way I am glad but in a way I am not, because of the things I went through.

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-009

Ricky and Louie, 19-years old.

1997

Louie: To survive outside in the world, there is a big challenge out there. Hate, jealousy, and envy, and to survive is to have money in your pocket and to have respect. If you feel you’ve got to stand on the corner, that’s your challenge; if you feel you’ve got to work to support your family, that’s another challenge. Our challenge is standing on the corner, so far so good, we survive. That day I look like I was stressed, thinking too hard, smoking weed. If you’re down, you can’t show it. Smoking feels good, it last for twenty minutes, and then if you don't have any money to buy more, you get more stressed. I used to be a badass, liked to fight, steal but then I learned. There is a better life out there. You got to go out and meet new people and be trusted and that feels good, you know. Monica, we were going through a lot of problems because of me. Instead of me talking to her, I used to walk away, smoke weed, thinking it was gonna help. And then coming back to the same problems cause I wasn’t talking to her, I was talking to the weed. But I have learned from my mistakes. My son is gonna know who I am, just by my reputation.

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-010

Ricky standing on his corner. Ricky never speaks about the future beyond next week, happy to make it through another day.

Maujer and Lorimer Streets, 1998

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-011

Monica gave birth to Louie’s child, a boy named Justin. While pregnant, Monica decided to move to Louie’s mother’s apartment in Flatbush. Louie was incarcerated at the time. After giving birth, Monica moved back home. Her parents supported her and Justin while she attended classes at Borricua College.

Monica: I am going to make it. I want to finish college and go on studying. I want to move to Florida and then to California. It’s going to be me and my son.

Lindsay Houses, 1998

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-012

Monica and her brother Diego.

Lindsay Houses, 1998

Diego: Brooklyn is a tough neighborhood. Everybody wants to be ghetto fabulous. If you want to do good, you've got to be a shadow.

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-013

Monica and Joel, aka Baya.

Union Avenue, 1999

Joel: I am in the rap game, trying to make it happen. Lived in the hood all my life... Monica and I met in Intermediate School 318. She has been the only girl I feel was competitive to my game. We could bond. She was independent.

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-014

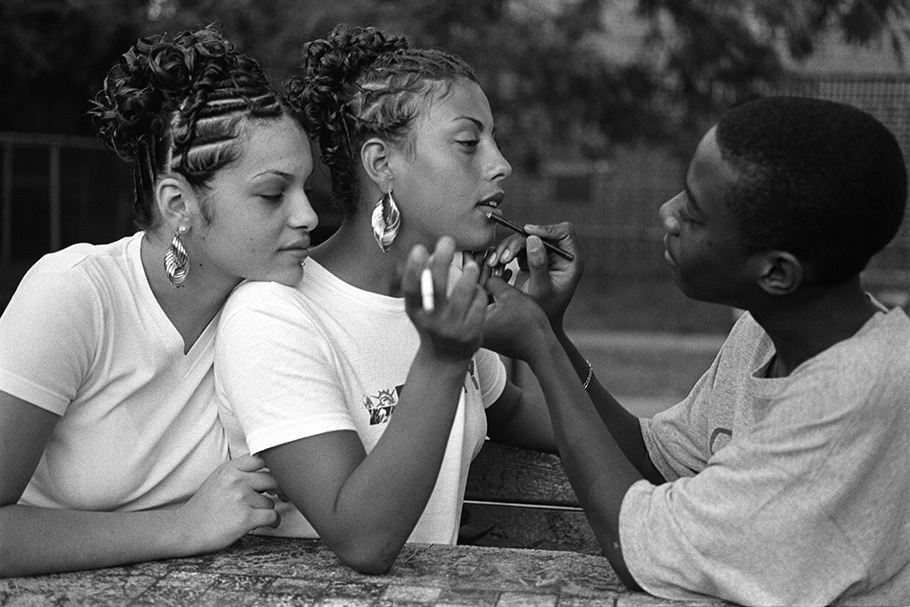

Monica, Jennifer, Biggie, and Nadia.

Broadway, 1999

Jennifer: I will never forget the girls. Me, Monica, and Biggie were always together, we had each other's back. If one of us was doing bad, we’d let her know, but we were always having a great time. We stuck together like glue. I was five months pregnant then. Monica was so happy. We all had the same twisties in our hair. We would have to stay for three hours under the dryer at the hair salon. We’d go all at the same time and use up all the dryers. Growing up here as girls, we worried about ourselves, had to take care of ourselves.

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-015

Biggie, Nadia, and Martin.

Caribe Gardens, 1999

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-017

Monica’s brother, Diego, and his girlfriend Lisa. Monica died from a bullet wound to the back of the head on New Year’s when she was 19 years old. The perpetrator was ultimately sentenced to one year in prison for negligent homicide.

Lindsay Houses, 2000

Diego: We were born a year apart. People used to call us twins. Monica was street-smart. She was overconfident, never afraid of anybody. She loved the nightlife. I guess the combination of being too friendly and wanting to have fun got her in a bad situation. What happened to my sister is going to haunt me and it is something that’s gonna keep me on point from whatever is out there. It hurts me a lot, but that’s what’s going to make me strong. I remember seeing my sister in the hospital, when I was told she had been shot in the head, that we had to pray cause she was on her way …. At that moment, I felt that I could blow up and just rip anybody apart, you know. The anger I had, it was the anger of an older brother. That was my beautiful little sister …. I pray for my sister every night before going to sleep.

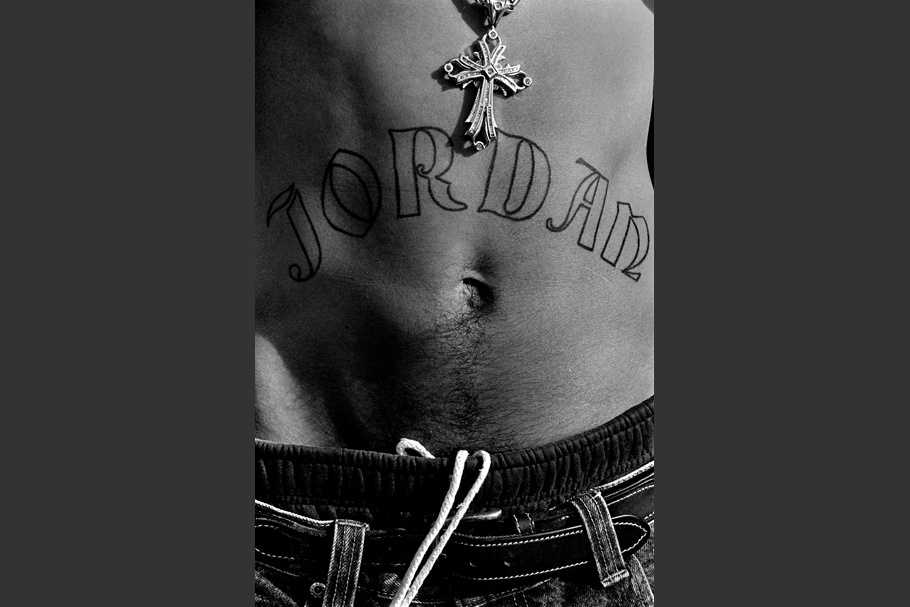

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-019

Cool V, a Maujer Boy, bearing his family name.

Maujer Street, 2000

20010606-monfort-mw05-collection-020

Jennifer, 20-years old, and Nadia with Jennifer’s seven-month old son, Jayden.

Manhattan Avenue, 2000

Jennifer: Nadia is cool, we have fun. She loves my baby. My life has changed since I met my baby’s father. He is sweet and treats me like a princess. Before I did not know what it was to be loved, to be treated nicely by a boyfriend. Once my son is two years old, I want to go to work, go to school. I am still young so I still have plenty of time.

Born in 1958 in Saint-Brieuc, France, Régina Monfort has lived in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, since 1992. Her work has appeared in CultureFront, Life magazine, Stress, and the Village Voice. She has exhibited in and her work has been collected by the New York City Subway, the New York Public Library, the Museum of the City of New York, and the Yale Art Gallery. Her work is also part of a collection at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Monfort has presented her work to the community she photographs by producing audio-visual presentations in some of Williamsburg's parks and vacant lots.

Monfort received a prize from the Columbia School of Art and grants from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and the New York State Council on the Arts. In 1998, her work was nominated in the Human Spirit essay category for the annual Alfred Eisenstaedt Award in Magazine Photography. In 1999, she completed a project at a high school in Des Moines, Iowa, exploring notions of identity, alienation, and belonging in America today.

Régina Monfort

In late 1994, I began photographing teenagers from the Puerto Rican and Dominican communities of Brooklyn’s Williamsburg section. Williamsburg is mostly known for its waterfront area and is often referred to as the “new East Village.” Only a few blocks away, beyond Grand Street, is another world where youth face the challenge of growing up without the benefit of the area’s progressive gentrification.

The neighborhood, despite economic despair, possesses a certain social cohesion, a solidarity at times volatile but nevertheless strong. Competition is fierce among the youth. Status is a matter of physical appearance and possessions. I asked a young man why he wanted a diamond-encrusted Rolex watch. He answered: “For the same reason an art collector wants a certain painting.” Initially I was even puzzled by the boys’ claim of their block, their corner. But I soon understood that surviving—much less succeeding—outside these boundaries is not always an option.

For some, the neighborhood is the only world where they can function. Social codes protect one’s prestige and authority. Anger can be valued as a survival tool. Many youth invest their trust in the language of hip-hop, which they feel, and understandably so, is the authoritative voice portraying their world. Growing up too fast, young girls strive to be perceived as women, and early sexual experiences become a desperate quest for love.

My work grows out of the personal relationships I have developed with the young people I photograph. I have come to see the tenderness and vulnerability so often concealed by the tough attitudes necessary to survive in their environment. Through my camera I look at the process of growing up in Latin Williamsburg as it unfolds—with its oddities and contradictions. The camera has, at times, served to validate the lives of some of the young people who feel forgotten. In turn, they have taught me endurance. From Grand Street to Lindsay Park, my lens has found hope as well as frustration. I have been asked, “Why are you here? Nothing is beautiful here!” The photographs are my answer.

I dedicate this exhibition to the people from around the way who have given me their trust, and to Monica who fought back whenever she faced a challenge. RIP, Monica.

—Régina Monfort, June 2001