20110316-roble-mw18-collection-001

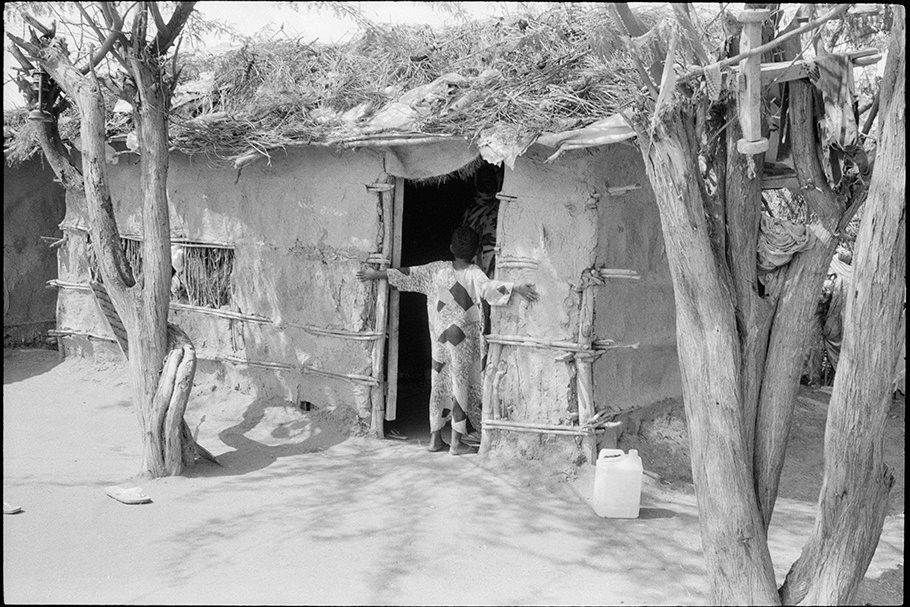

Farhiya in the Doorway

Dadaab, Kenya, December 2005

Farhiya was raised by her cousin Abdisalam’s family. She stands in the doorway of their living room, which is done in an architectural style typical of Dadaab.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-002

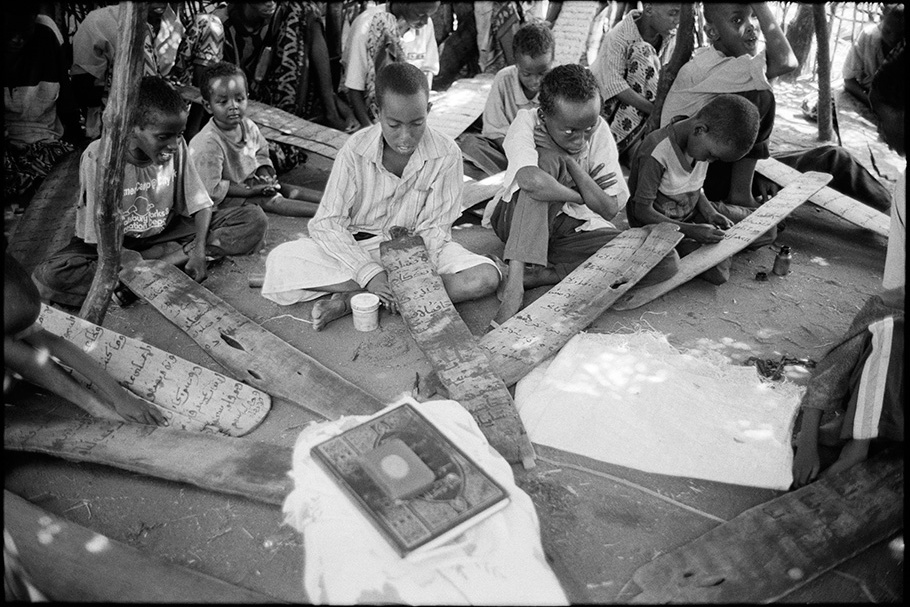

Qur’an School 1

Dadaab, Kenya, November 2005

These children are memorizing the Qur’an. They write a verse on one side of a board and turn it away from themselves, toward their teachers, as they recite the verse aloud. When the Sheik is satisfied that the children have memorized the verse, he will allow them to erase it, and the process will begin again with the next verse.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-003

Walking

Dadaab, Kenya, December 2005

After gathering grain, cooking oil, and water supplies provided by CARE International, this mother and daughter must carry their supplies through the desert and back to their home.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-004

Building Materials

Dadaab, Kenya, November 2005

This woman carries thatch that she will use to repair the roof of her home. It will take her the better part of a day to gather it, as she must walk several miles to find enough vegetation to provide the roofing material she needs.

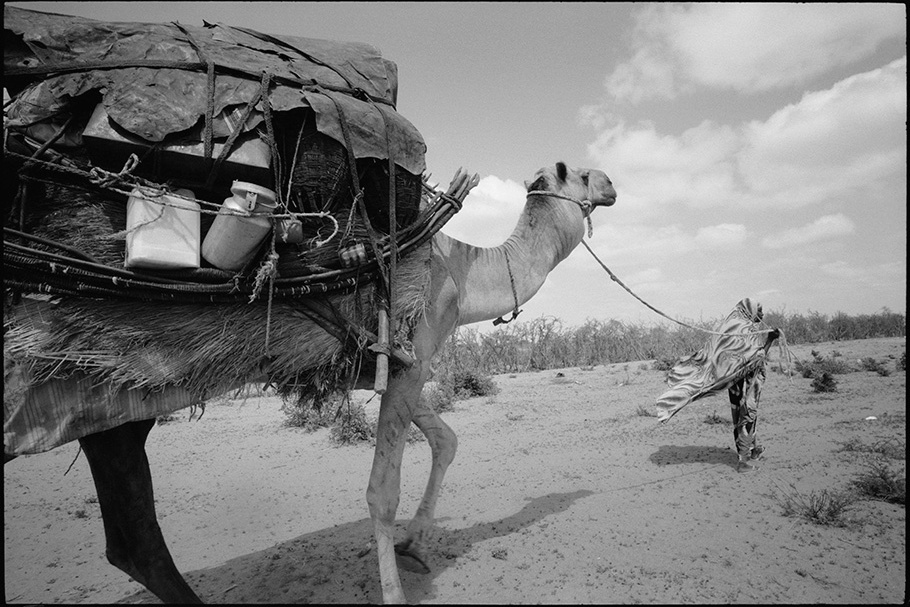

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-005

Camel

Dadaab, Kenya, December 2005

Nomads in this part of Kenya are Somalis. They travel from one watering hole to another to keep herds of goats and camels alive. Somalis are proud of their camels and proud of their ability to drink camel milk, which they think brings health. Many people think that the word “Somalia” derives from the phrase, “So mal,” which means “milk the camel.” This phrase is uttered when guests arrive and regarded as a symbol of Somali hospitality.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-006

Feeding the Goats

Dadaab, Kenya, December 2005

Ijabo appeared extremely thin when we photographed her feeding the family goats. We were horrified to learn that she had been giving her share of the cornmeal to the goats so that her daughters could have milk. Ijabo was terribly malnourished, and she became pregnant before her family left the camp. If they had not been resettled to the United States, she may not have survived.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-007

Looking into the House

Dadaab, Kenya, December 2005

Cousin Asha looks in on the children of Abdisalam.

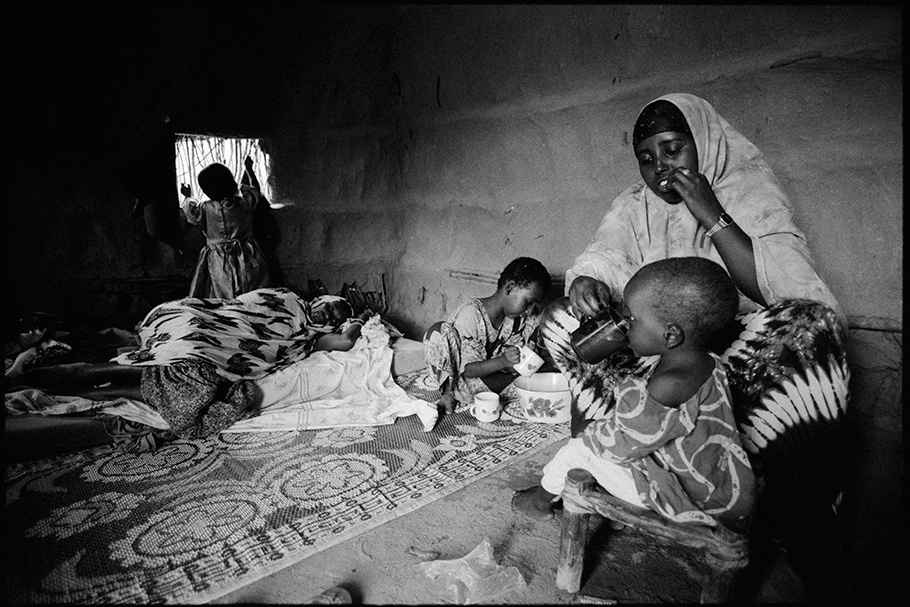

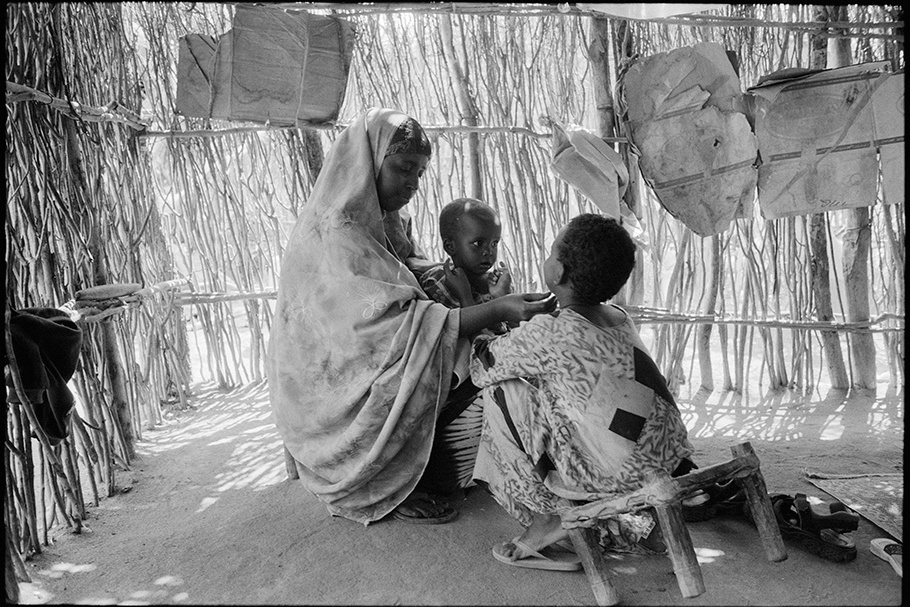

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-008

An Aunt’s Visit

Dadaab, Kenya, December 2005

Abdisalam’s sister, Sadio Abdirahman, cares for the children. She has come from Somalia to visit her brother and his family. She will return when Abdisalam immigrates to the United States.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-009

An Aunt’s Last Words

Dadaab, Kenya, December 2005

Sadio speaks with her nieces before the children leave for America.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-010

Their First Meal

Anaheim, CA, February 2006

The refugee camp actually offers fewer calories than human beings require to survive. The camps are also both practically and legally unable to cater to eating requirements of particular cultures. This family’s first meal in America is also their first traditional Somali meal in eight years. After they finished eating, they said that the last time their stomachs were full was eight years ago, before they were forced to flee to Dadaab.

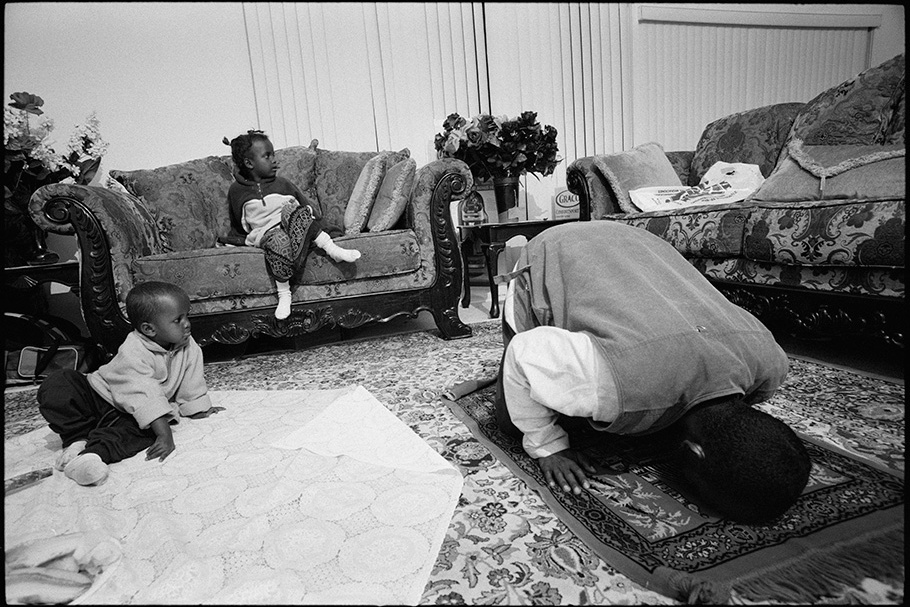

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-011

Praying in Ibrahim’s House

Anaheim, CA, February 2006

Abdisalam feels fortunate that Ibrahim, the social worker who picked him and his family up at John Wayne International Airport, was also Somali. Ibrahim invited the family to spend their first night in America at his house.

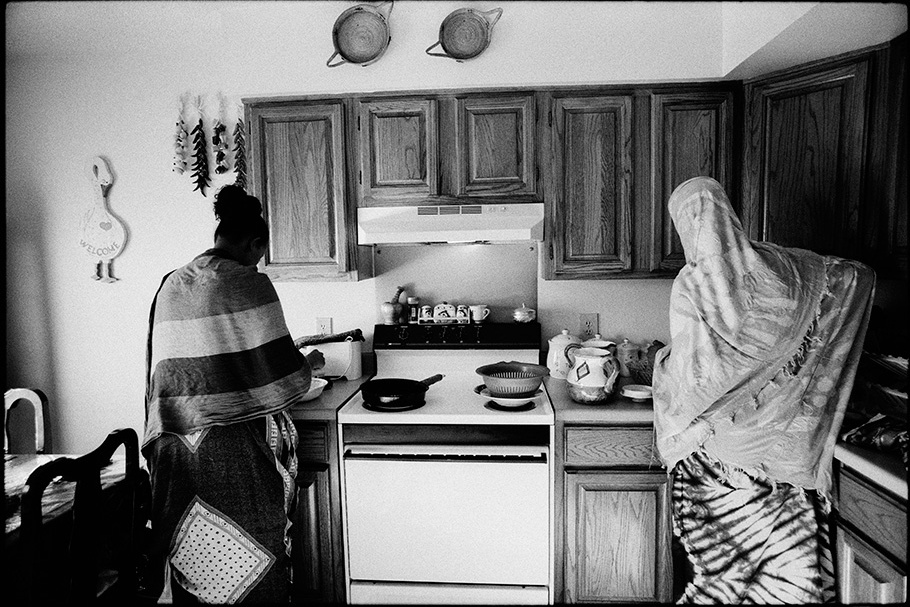

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-012

Somali Hospitality

Columbus, OH, May 2004

The kitchen is the center of Somali social life. Friends drop into Somali households, unannounced and unexpected. No one asks if the guests are hungry; the women simply start preparing an elaborate meal that usually involves rice and goat meat.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-013

The Vacuum

Anaheim, CA, April 2006

Electric appliances are a new phenomenon for Ijabo. Her family moved from a home with dirt floors to one in which Ijabo relies on mechanical help to remove dirt from the carpet.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-014

Women Outside

Anaheim, CA, April 2006

Farhiya, Sadio, and a neighbor talk outside the family’s new apartment complex. The amount of time Somalis spend outside may seem odd to Americans, but in Africa, the appliances that keep American homes comfortable are not readily available, and many immigrants are accustomed to spending most of their days outside socializing with friends. Somalis also feel free when they are outside.

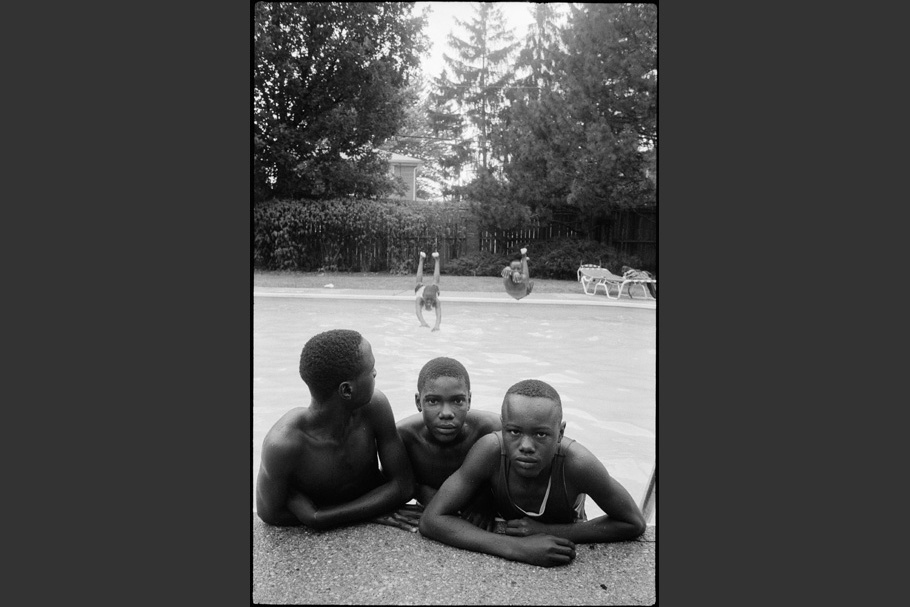

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-015

Boys Playing in Pool

Columbus, OH, July 2004

Teenage boys who had grown up in a refugee camp enjoy a dip in the pool at their apartment complex.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-016

Somali Jazz

Minneapolis, MN, October 2006

Ismahan entertains her brother Fuad with her musical skills.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-017

Girls’ Basketball

Minneapolis, MN, January 2007

These girls attend Minnesota International Middle School, part of the school started by Abdirashid Warsame, who is currently the school’s principal. At this largely Somali school, boys and girls exercise separately, but both get exposure to athletics and team sports.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-018

Eid ul-Fitra at the Mall of America

Bloomington, MN, October 2006

When the month-long fast of Ramadan is complete, Muslims celebrate Eid in Minneapolis by taking their children to the amusement park at the Mall of America. Approximately 30,000 Somalis gathered there in 2006 to commemorate this Islamic holiday.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-019

SEIU Rally

Minneapolis, MN, October 2006

These Somalis are members of the Service Employees International Union, which represents janitors and other service employees. The women wear special hijabs that are the color of their union. Some people see the hijab as a sign of weakness, but for these Muslim women, their hijabs represent their strength.

20110316-roble-mw18-collection-020

Protesting

Columbus, OH, December 2005

Nasir Abdi, a mentally ill Somali man, was shot dead by Franklin County Sheriff’s deputies 60 seconds after they arrived on the scene. Earlier, Abdi’s parents had called Netcare, the county’s mental health crisis intervention center for help when their son began acting erratically after he stopped taking his medication; Netcare in turn called the Sheriff’s office. The Somali community believed Abdi’s shooting death to be unjust and staged protests in front of city hall.

Abdi Roble is a documentary photographer with a vision for social justice. His photographs of the Dadaab refugee camp cry out for an end to the inhumane conditions, just as his images of striking workers demand culturally sensitive working conditions for refugees. In 2005, he exhibited his work about the local Somali community at the Riffe Gallery in Columbus, Ohio. A year later he presented Against Forgetting, Beyond Genocide and Civil War at Intermedia Arts in Minneapolis, Minnesota. From 2007 to 2010, another body of work about Somalis, Stories of the Somali Diaspora, appeared at museums in Maine, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Ohio. The work also went abroad for inclusion in an exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Santiago, Chile, entitled 100 Years of American Art: A Social Perspective, 1910-2010.

Roble received Individual Artist awards in 2004 and 2006 from the Ohio Arts Council and the Greater Columbus Arts Council. The South Side Settlement House honored him in 2006 with the Arts Freedom Award. In 2009, Roble received the Raymond J. Hanley fellowship Award.

Working with writer Doug Rutledge, Roble provided photography for The Somali Diaspora: A Journey Away, a book published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2008. Roble has also presented courses and lectures on Somali culture and the Somali Diaspora at the University of Minnesota, the Museum of World Culture in Frankfurt, Germany, and the universities at Oxford and Leeds in England. Roble is currently a visiting scholar at the Center for African Studies at Ohio State University.

Abdi Roble

The Somali Documentary Project grew out of a developing set of related needs: those of refugees to tell their stories and the needs of hosting community members to understand their new Somali neighbors and coworkers.

The notion of community for the Somali people is different from that denoted by the English word. Because of their nomadic heritage, Somalis think of communities involving people as opposed to space. In the wake of the Somali civil war, which started in 1991, the Somali community has truly become transnational; husbands, wives, brothers, sisters, and cousins are often separated by national borders and languages, but still belong to a larger Somali community.

I left Somalia before the civil war erupted. For me, the idea and challenge of the Somali Documentary Project arose when I saw so many refugees arriving in Columbus, Ohio, where I live. I wanted to tell the story of these refugees, but felt that in order to do so I should document the entire transnational community. I decided to travel to Minneapolis, Minnesota, the largest Somali community in the United States as well as to Anaheim, California, and Portland, Maine, so I could follow the resettlement process of refugees and their secondary migrations.

More importantly, to tell the stories of these refugees completely, I also had to travel to the Dadaab refugee camp in northeastern Kenya where the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees attempts to provide sanctuary for people as they flee the civil war in Somalia. When I went to the refugee camp in 2005, I had been away from Somalia for nearly 20 years. Like most Somalis, indeed most refugees, I missed my homeland. Now, because of the civil war, the closest I could get to home was the camp.

Encountering the people I had left behind and seeing them in such terrible conditions was a very emotional experience. The first people I met were unloading grain. When I saw how hard they worked and realized what a pitifully small reward they received, I cried. The workers warned me. “We’re the strong ones,” they said. “If we make you cry, please don’t go inside the camp.”

I realized that if I was going to do my job and tell the story of these people through photographs, I would have to overcome my emotions or turn them into an artistic statement. But how should I portray my own people in these conditions? The last time I saw people in my homeland, they were happy and prosperous. Somalia was an important country on the Horn of Africa. But today many of those Somalis who try to escape the war are confined to refugee camps. I had to be truthful to the inhumane conditions I witnessed, but I also had to capture the integrity and the dignity of these people I knew so well. The camp, with its harsh light, also presented a number of technical challenges, but the bigger issue I faced was the emotions inside of me. Instead of emphasizing the refugees’ suffering, I found a beauty in the way they made their difficult plight into something that contained the daily rhythms of an ordinary life.

I offer my images of the Somali people to reveal both their dignity and their suffering.

—Abdi Roble, November 2011