20110316-drake-mw18-collection-001

A street scene along a canal, near the border between Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan in Osh province. Water, electricity, and gas are often only sporadically available along the artificial borders between the countries touched by the Syr and Amu Darya rivers, and the irrigation canals funneling water to and from cotton fields are poorly maintained.

Kyrgyzstan, 2008

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-002

Paintings on the walls of a dilapidated spa in the autonomous Karakalpakstan Republic depict the formerly idyllic and lush landscape of the Amu Darya delta.

Uzbekistan, 2010

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-003

The city of Khujand viewed from a window in the Leninabad Hotel. The city was established by Alexander the Great 2,500 years ago on the banks of the Syr Darya (shows in the upper left corner of this photograph).

Tajikistan, 2009

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-004

A reservoir above Nurek dam in Tajikistan. The overall water supply will continue to diminish in the future. The water that nourishes the whole region comes from melting glaciers and snow in the mountains of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. During Soviet times, decisions about sharing resources were made by the central government in Moscow. Now, the countries are constantly disputing how the region's dams should be used--downriver countries want the water to be stored in reservoirs in winter and released for irrigation in summer, while upriver countries want to release it in winter to create electricity.

Tajikistan, 2009

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-005

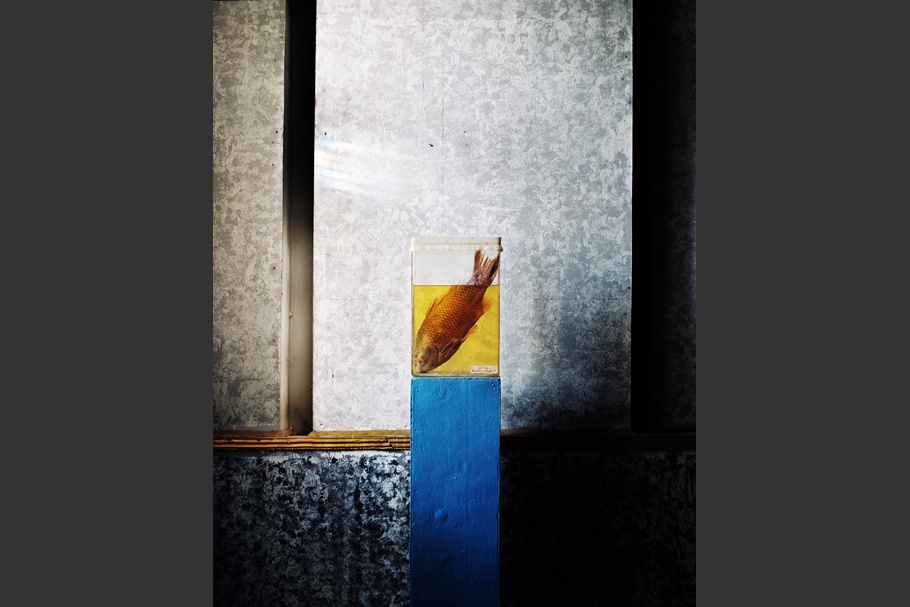

A fish from the Aral Sea in the History Museum of Aralsk, a formerly bustling Soviet fishing port on the Aral Sea. The animals in the museum were placed in Kazakhstan's "Red Book" of endangered species. As water from the Syr and Amu Darya rivers was diverted for cotton farming, the Aral Sea and the ecosystem it supported began to deteriorate.

Kazakhstan, 2009

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-006

A swimmer on the starting block in Mary, a city developed as a center for cotton production in the Soviet Union.

Turkmenistan, 2008

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-007

An Uzbek woman whose family follows Shariah law poses in the courtyard of her home. Her town was split between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan when the Soviet Union came apart in 1991. With its crumbled infrastructure and little opportunity for economic advancement, this region is home to some who are attracted to political movements aiming to unite all Muslim countries into a single Islamic state. The population of the Fergana Valley was devoutly Muslim before Soviet times, one of the major reasons the Soviet Union wanted to divide the area and weaken the religious bonds that were part of the fabric of life here.

Kyrgyzstan, 2007

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-008

The remains of a typical Central Asian meal—plov, tea, candy, fruit, and bread—at Dargan Ata, a pilgrimage site where the water is considered sacred.

Turkmenistan, 2009

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-009

Islam spread through Central Asia in the eighth century and mixed with local shamanistic beliefs. After the Soviet ban on religion was lifted in 1991, the region's spiritual traditions revived. Traditional healers use tools such as knives, whips, candles, and incense to wash away evil spirits that are believed to cause physical and psychological ailments.

Tajikistan, 2008

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-010

A Tajik woman lives with one of her daughters in a village of cotton farmers. Like most other men in their village, their husbands have left to find migrant work in Russia.

Tajikistan, 2008

20110316-drake-mw18-collection-011

Families celebrate the spring holiday Navruz in a restaurant in Kokand in the Fergana Valley. At the crossroads of ancient trade routes, Kokand has existed since the 10th century and is a major religious center in the Fergana Valley, one of Central Asia’s most densely populated regions. Earlier Soviet policies of divide and conquer split the valley into what are now the independent states of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

Uzbekistan, 2007

Carolyn Drake was born in California and earned her bachelor’s degree in Media/Culture and History from Brown University in 1994. Drake went on to study photography at the International Center of Photography and Ohio University, and worked as a multimedia producer in New York for many years before launching her career as a documentary photographer.

Drake seeks clarity by immersing in the periphery, and has focused on environmental and cultural issues in Central Asia since 2007. Her previous work includes Wild Pigeon, which explores the Uighur encounter with Chinese expansion in Xinjiang; Coal Town, an intimate view of a Soviet mining town in the Donetsk coal basin; and The Lubavitchers, about a community of Hasidic Jews searching for mosiach in Brooklyn.

Drake is the recipient of a 2006 Fulbright Fellowship to Ukraine, the Lange Taylor Documentary prize in 2008, and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2010. She has received recognition from numerous photo competitions, including World Press Photo, POYi, UNICEF, and Review Santa Fe. Drake has lectured frequently, and she recently exhibited her work from Central Asia at The Half King Gallery in New York, The Third Floor Gallery in Cardiff, Wales, and the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, England. Drake currently lives in Istanbul.

Carolyn Drake

“As others have before, I turn to the past to see what I am. I follow the river which offers truths that can’t be denied. Distraught by where we’re going, I look back, for lessons to be learned. Against the flow, I look. Maybe this is the same thing that brought us where we are.” —Loren Eiseley, The Immense Journey

Medieval Islamic writings refer to the Amu Darya and Syr Darya in Central Asia as two of the four rivers of paradise. The water they yield has sustained human life for 40,000 years, providing pastures for nomadic herders, irrigation for farmers, and enabling the development of culture, trade, language, literature, and—in parallel—a succession of wars and imperial conquests over the centuries. When the Soviet government officially incorporated the region into its empire, it began transforming the rivers into a web of irrigation canals that brought cotton production to the area on a massive scale. Such large quantities of water were diverted that the Aral Sea, once the world’s fourth largest inland sea, began to disappear, leaving salt and dust storms in its place. When Moscow’s rule ended in 1991, five new Central Asian nations—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—emerged and were burdened with plunging economies, artificial borders, and a growing environmental crisis.

Despite the divisions that have formed since the Soviet Union collapsed, the two rivers that run through the countries of Central Asia still bind them inextricably. This project follows the rivers from beginning to end through five countries, crossing into the lives of people and layers of history that they intersect along the way.

The Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers are bodies of water where the connection between the earth and human life is complex and immediately visible. Cotton harvested on toxic, pesticide-contaminated land is later burned in a ritual celebrating rebirth and spring. Farmers who practice an Islam that prizes adaptation and views jihad as an inner struggle create electricity from mountain streams. The Karakum Canal, which runs 1,400 kilometers through Turkmenistan, is the world’s longest canal and has turned barren desert into a lush landscape of fishing, farming, and beekeeping. Dust storms and illness have overtaken land that was once fertile, ancient towns are divided by international borders, and the absence of plumbing and electricity is not because of a lack of supply but a result of politics.

I am interested in the lives of people who live along these rivers and those who are most affected by the dramatic changes that governments and empires have imposed on the landscape. Seeing the ways that history has divided and weakened these people, I focus on what connects them, the rivers. In doing so, I aim to look at what came first—what initially enabled life to emerge along the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers—and explore the consequences of what has been done in the name of progress.

—Carolyn Drake, November 2011