20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-001

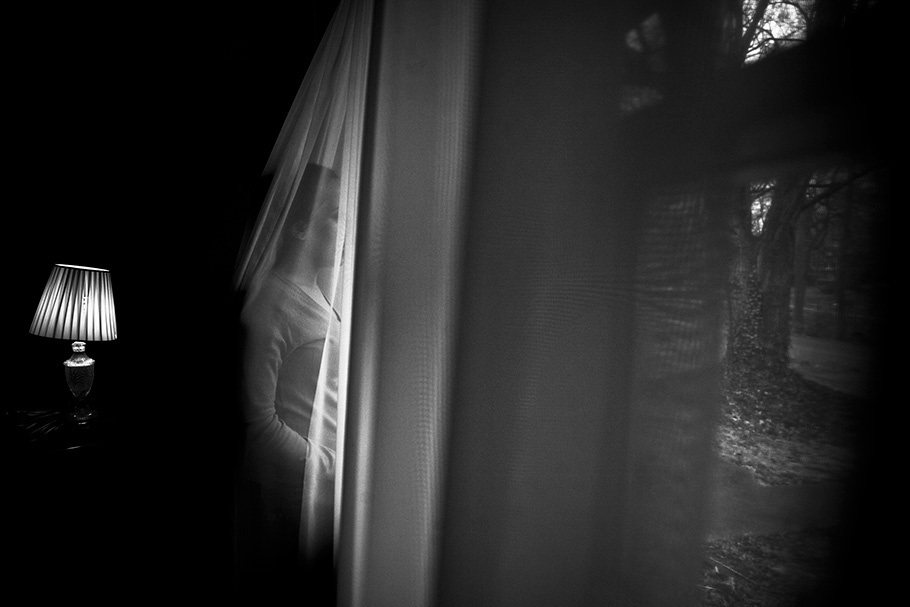

Three generations of Iraqi women—a grandmother, a mother, and a daughter—were violently separated and forced to flee to three different countries. Now, after three years apart, they are finally living together as new American residents. Yet, even in the United States, they live in hidden exile, unable to reveal their identities for fear of being discovered by their male relatives and Iraqi anti-American forces. The mother, a former Coalition Provisional Authority employee, was labeled a “collaborator” and was targeted for assassination. They rely on their strong Christian faith to remain hopeful about their future in the United States.

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-002

“Before, when people told me, ‘you cannot establish yourself in United States’ and told me about being ‘homesick,’ I would laugh. But it’s very difficult: you always feel you are missing something. I do miss friends, family, even the old streets, the poor people—everything! It’s difficult to come here alone, even if you have friends. It’s a very big challenge and I am not sure if I can stay here or not. If you have never been a refugee in another country, if you never had the opportunity to feel that, you will never understand. If the situation improves in Iraq or even if it is worse, maybe I will go back.”

201103016-bulisova-mw18-collection-003

“The threat came in early 2006. Like many Iraqis, I got the white envelope with a bullet in it and with a very short message: ‘Leave your house, leave your town, or death is coming to you.’ They gave me just 24 hours to leave...and I left. I received the threat because I was working with the United States Army, with the United States Marine Corps, with the MPs—the military police in my city.”

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-004

"I found most of the Iraqi refugees here are struggling to survive; they do not really receive real assistance to address their situation. The agencies that are supposed to be helping are making life more and more difficult for us. They are very uncooperative, very unhelpful, and have done nothing for us. I have told this to them directly."

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-005

"I am an Iraqi person who came to the United States as a refugee. I am originally from the south of Iraq. I escaped death several times. I was working with the U.S. Army in Iraq in different positions for several years. I basically became marked for death because a lot of information got into the terrorists' hands. They sent me a text message saying: 'We will cut you into a hundred pieces and will throw you in front of your door.' I knew it was not a joke. My friend, they slaughtered him. They put his head in front of the door. Another friend, they kidnapped her, and I understood from her that they raped her. And another friend of mine, she was shot along with her driver. When they shot my friend, I understood that they knew many things about me. I knew I would be the next one. And because my sister and I both worked for the U.S. Army, I knew they would kill us both, if not our entire family. I had to take action, not just to protect myself, but to protect my family."

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-006

"I feel the United States may adopt me, but not yet. I don't feel like myself in this country. I feel I am besieged by worries and uncertainty. There is only a vague sense of future and hope. At the moment, I have nothing. I have a cold room. I am living in a bad situation. Who will look after me? Yes, there is appreciation: thank you so much United States of America, you provided me with freedom, but what is next? I am not a lazy person. I want to work, but where is the work? I used to be a general surgeon in my country, but not now, I am nothing here. It is just like...life starts from zero, and it has not yet started."

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-007

“I don't know if I will be able to get back to Iraq...it's a difficult position. As hard as it was to leave Iraq, it is also difficult to get back there. I did not think for one moment that I would miss that place where I lost my brother and where people were chasing me and trying to kill me for no reason. Because a person goes to work is not a reason to kill them. Yet I miss Iraq and, especially, I miss my family. Sometimes here, I feel I am very much a foreigner.”

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-008

“I am a very normal guy, with a very normal lifestyle. My only fault is that I was born an Iraqi."

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-009

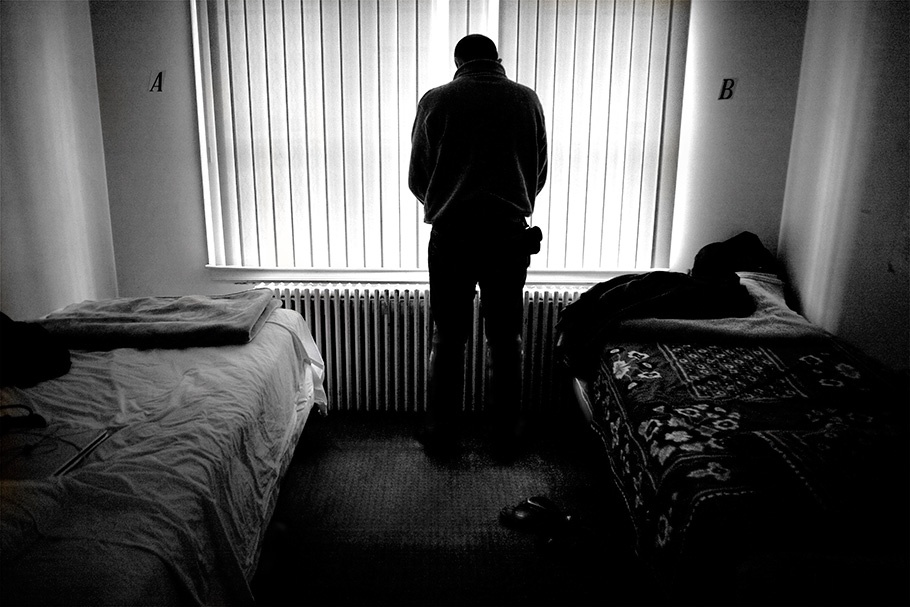

"When this man and his family of six resettled to the United States, they had great hopes for a life of privilege and a warm welcome. They looked forward to starting their lives anew in a country that had promised to take care of them, a country where they would not have to fear death and violence. They soon encountered a reality, however, that was far from what they expected. Isolation and a lack of financial support and employment opportunities have shaped their experience in the United States. These difficulties have taken an emotional toll on the family as they try to manage the stress, despair, and disillusionment that has come with living a life in exile."

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-010

“I have been here eight months. I feel I am safe, but also my life is difficult. Everyday, I try to tell myself that the next day will be much better, but I don't really think this is so. For other refugees who have no help, no support, living here is even more difficult. I feel I am luckier than other people because I have friends who are helping me, supporting me, but other people who don't know anybody...I don't know how they manage. Those Iraqis who don't speak English...I don't know how they get by here.”

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-011

“Yesterday, I was shouting during my sleep. Then, I woke up suddenly. I found myself sweating...my dream was really scary, it was about Iraq. If you live as a refugee or an asylum seeker, or anyone who was suffering inside of Iraq, you would feel this pain that lives inside you and shows how you are really, really suffering; struggling for survival.”

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-012

“When you start losing the people who are closest to you, when you start seeing your loved ones suffer and fall--this is the day when you cannot continue. This is the day when you realize you have become a threat to those you love because you are now a target of the terrorists and the people who don't want life to continue. I lost many, many people, but the biggest loss was my girlfriend. That was when I came undone. It happened in 2006, in January. It was a big explosion, a bomb at the University of Baghdad. I was lucky that day because she did not die. I went to the hospital and spent four days with her...and then she died.”

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-013

"I am Republican. I am a new resident. I am eligible for a green card and will apply for citizenship. I am not an Iraqi and I am not an American: I have no roots anywhere."

20110316-bulisova-mw18-collection-014

“I hope that one day people will listen--just to understand our situation. We are not waiting for any help. We are waiting for people to understand why the Iraqi people became refugees. Sometimes, I feel we are lucky because the war happened and the United States kicked out Saddam and his army, but what is the result?”

Gabriela Bulisova is a documentary photographer from the former Czechoslovakia who is now based in Washington, D.C. She carries her camera to marginalized communities in places such as Azerbaijan, Ukraine, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria. By bringing the faces of the forgotten to light and giving voice to those who have been silenced, she hopes to capture people through the lens of an advocate, rather than a dispassionate observer.

Bulisova has received numerous recognitions and awards including the Aperture Portfolio Review Top Tier Portfolios of Merit, the CANON “Explorer of Light” award, a CEC ArtsLink Projects grant (2005), the Corcoran School of Art and Design Faculty Grant Award, a PDN Annual Photography Competition Award (Student Category), and a Puffin Foundation Grant. Bulisova was a participant at the Eddie Adams Workshop for emerging photographers (2006) and a graduate fellow at the National Graduate Photography Institute, Columbia University (2004).

Bulisova received her Master of Fine Arts in Photography and Digital Imaging in 2005 from Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. She is currently an assistant professor of photography at the institute and at George Washington University, Washington, D.C. Bulisova is a member of the Metro Collective Photographic Agency and the Women Photojournalists of Washington.

Gabriela Bulisova

One of the least reported stories of the U.S. invasion of Iraq is the dispersal of close to 5 million Iraqis displaced either internally or forced to flee across the country’s borders. This exile is one of the greatest refugee crises in modern history—the statistical equivalent of nearly 50 million Americans leaving the United States. These masses of people displaced by the war in Iraq have become invisible and insignificant, overshadowed by other war-related events. Many of the displaced were the brains, the talent, the pride, the future of Iraq. Many of them, stigmatized by unforgettable violence, will never return to their homes.

In 2007 and 2008, I traveled to Syria to photograph Iraqi refugees living in Damascus. I found them in dire economic and emotional straits—often traumatized, desperate, and disillusioned. Uprooted from their homes and families with no future and no hope for return, they bear witness to the lesser-seen, lesser-known consequences of the war. I wanted to tell their stories.

While working in Syria, I heard about the plight of Iraqis who were forced from their homes specifically because they had helped the United States. Some of them had made it to America where they were having experiences and feelings both similar to and different from those of Iraqi refugees who had remained in the Middle East. By focusing on the struggles of those in the United States, I hope to create greater understanding for both the Iraqi refugees in our midst as well as the millions who are largely out of sight in Syria and the Middle East.

Some of the most recent Iraqi refugees in America had signed up to serve as translators working for the U.S. military or as experts with other U.S. government agencies, NGOs, or American companies in Iraq. They saved lives; they built cultural and linguistic bridges; they sacrificed their own safety and the safety of their families to help participate in what they thought would be the creation of a better Iraq. They quickly became one of the most hunted groups in the country. They bore a lethal stigma as “collaborators” or “traitors” that transcended sect or tribe, and they were targeted in assassination campaigns that drove many of them either into hiding or out of the country.

For people who fear for their life and seek refugee status in America, the U.S. government offers resettlement as the “option of last resort” for the most vulnerable refugees. In this project, I photographed and interviewed Iraqi refugees who have been resettled to the United States and are living in Washington, D.C. or other American cities.

In some respects, these immigrants might be considered lucky, since they made it safely out of Iraq where their lives were in immediate danger. Thousands of others are still in Iraq or neighboring countries. In fiscal years 2007 and 2008, the Department of State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs issued only 1,490 special immigrant visas for Iraqi translators and interpreters who had assisted the United States. This number includes family members.

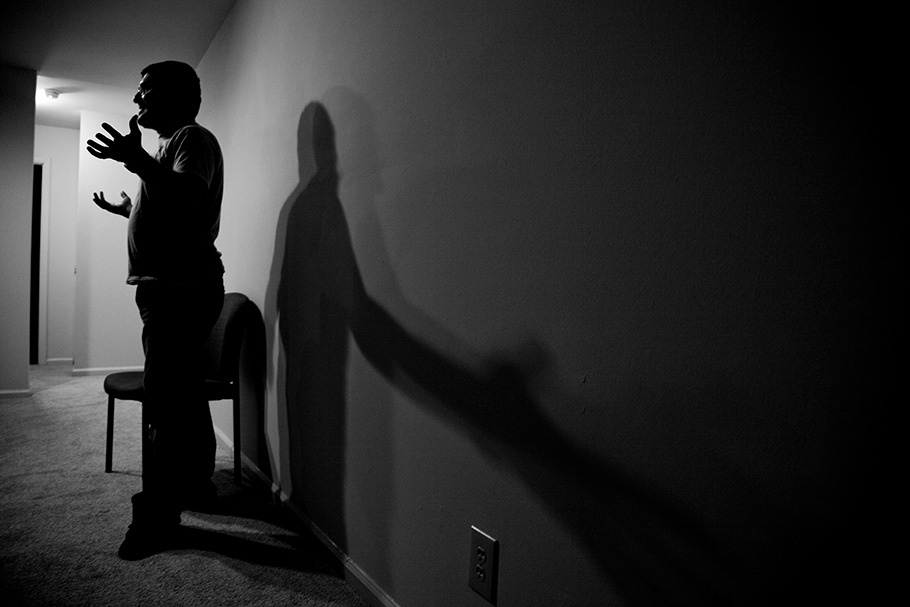

Once in the United States, these refugees encounter the intricate, challenging, and often disillusioning process of transitioning to life in America. Many feel abandoned by the country they helped and risked their lives for; many are unemployed and facing dire financial crises; many yearn for the embrace of family and friends left behind; and many wish they could return home. Still fearful for their own safety and the safety of family members in Iraq, many refugees asked that I not reveal their faces or names.

Under President George W. Bush, questions about assistance and safety did not receive serious attention until 2007 when Congress passed legislation to facilitate asylum for Iraqis who had aided the United States. As a presidential candidate, Barack Obama declared, “We must also keep faith with Iraqis who kept faith with us. One tragic outcome of this war is that the Iraqis who stood with America—the interpreters, embassy workers, and subcontractors—are being targeted for assassination. Keeping this moral obligation is a key part of how we turn the page in Iraq.” However, a new challenge is emerging as the United States cuts back its military presence in Iraq and has less ability to protect the Iraqis it employs.

—Gabriela Bulisova, November 2011