20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-001

The bill will decide the future of gay people in Uganda. If the bill comes, we as activists will be the first ones to be arrested. They know us.

I used to be religious, but I’m not anymore. I lost my religion because of all the hatred preached by the Christians here. I’d rather go to my room and pray by myself to God. I know that God is there.

This guy asked me whether I was married. I said no, I love men, I don't love women. He was interested, we exchanged numbers. We met the next day and he took me on his boda (motorcycle). Then he said he had run out of fuel, so I got off. There were policemen waiting. One slapped me. The one from my tribe said I was shaming them. He said he would call the media and put my picture in the newspaper. I got very scared. They took me to the police station. I had to write that I wanted to sodomize the guy. I refused. They were humiliating me, pushing me with their guns. They told me the guy wanted 1.5 million shillings. I had 15,000 in my wallet. They took it. I said I could raise only 300,000. It was money to pay my brother's school fees. I hired a taxi and went to my place with two policemen. The driver and one policeman stood outside. I went inside with the other policeman and gave him the money. I was released at 3:00 am.

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-002

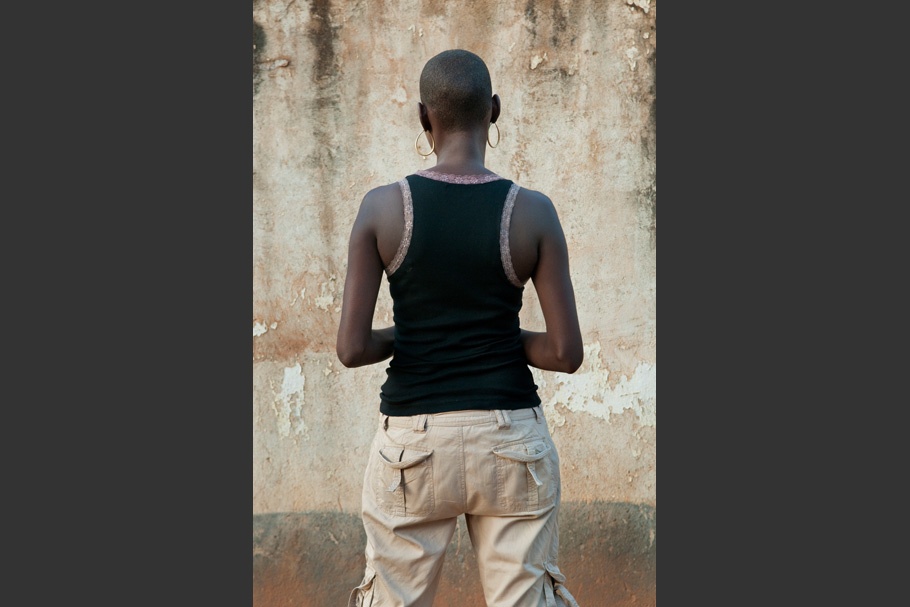

The problem is the way I dress. Everyone asks, "Is that a boy or a girl?" In clubs, when ladies can get in for free, they push us, tell us we are not ladies and that we have to pay. They scream, "Is she a boy or a girl? Is that a man or a woman?" As a tomboy, everyone looks at you.

If I am gay and not disturbing other people, minding my own business, why would they take me to prison? I am a peaceful person, why would they kill me? We won't be free, especially us, tomboys. They can suspect we are gay and, if the bill passes, anyone can tell the police. I will not change the way I dress, the way I look. That's me.

My family suspects. If I tell them, they will hate me. My brother once read texts on my phone that I sent to my girlfriend. He asked me if the messages were going to a guy or a girl. I didn't answer.

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-003

My family, they all know, but they never speak about it, except my sister and my cousin. Especially since the article came out in the Red Pepper newspaper and my nephews were running around with the paper. My younger sister asked me. I first said no, but then with the article, I said yes. She said a lover of hers asked her and that the relationship ended because of it. The family distanced itself from me for about five years. Only in the last two years did things get better.

This guy I know stole my phone. People were calling and he told them: "he is homosexual and he's gonna be arrested." My boss came and asked me about it. I told him. I'm here, let the police come and arrest me.

I accepted myself when I was 25. I had this partner, a friend. He told me, "If what you do makes you happy, then go ahead and do it." I didn't get it at first. Later I rephrased it. "If being gay makes you happy, then do it."

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-004

In the bill, they mixed homosexuality with rape and assault. They can't compare us to animals, witch doctors, rapists. We are normal people who love each other. We're not here by choice. If you're gay, you're gay. Accept it.

I don't go to church. The church criticizes homosexuality too much. They say it's madness. We are believers, but can't go to church. Wherever we go, they talk about homosexuality. They think we do it for money.

In bars, people insult me. We play pool and they say, "are you a man or a girl?" They want to fight me, threaten to rape me. A few years ago, my stepmother saw me on TV when my lesbian organization ran a workshop. When I came back home, she insulted me, made fun of me. She even went to my landlord, told her to send away "this evil." I wasn't ready for that. I had to hide until my organization found me another place.

I don't want to go back in the closet. I really want to stay here. I love home. I can't run forever.

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-005

People try to call you and blackmail you. It happens a lot. You can't tell who the phone calls are from.

I think if the bill is passed in the parliament, the hunt will begin, the witch hunt. Raids and blackmail will intensify. They will feel encouraged by the law.

Right now there is no future for the gay community. Right now we are just hoping and praying.

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-006

I want to live my life freely. Kiss, hold my girlfriend freely. Get married like straight people. Have the same opportunities as straight people. Own property. Most gay people who can afford to buy property put it in their brother's name. They invest, but not openly. If people find out that “the house belongs to a gay person,” they can set it on fire.

I was sexually harassed by colleagues at work. Every day I left the office late. One evening, a colleague also stayed late, pretending he had work. He started touching me. I told him I don't like guys.

At that time, some butch friends were coming for lunch regularly. Then there was a story in Red Pepper that I am dating one of them. I found photocopies of the article on the notice board at work. I became extremely paranoid because of the attitude of people I worked with. One month after the article came out, I took sick leave. When I came back, they let me work one day, then terminated me. Later, my boss called me to see if I was ok. He asked me if I was a lesbian. He told me he had no problem, but that people at work had complained about me. “Guys wanted a fuck,” he said. Then they used the article as a scapegoat and fired me, because I wouldn't give them a fuck.

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-007

When the bill proposal came out, my family was at first worried because, according to the bill, they had to report me. I told them to relax. The bill stresses me out. I just want to continue with my life. I will stay here. It is my home. I will fight it. A piece of paper will not take me abroad. I don't want to stay here to be a hero, but it's the only place I know. I love it so much.

I've been threatened with rape to show me I am a real woman. I get harassed everywhere, in public transport, the market, streets, bars, restaurants.

I don't want to give the impression that it is so impossibly hard here. It is tough, but not that hard. People even fear to come here. I would like them not to have the picture that it is so terrible.

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-008

In secondary school I realized I was a lesbian. I wanted to change, love men. I burned all the letters from women that I got. I fasted, prayed, wanted to get a boy. The person I was dating then, I told her we are sinners, we should take a break and find male partners. But it didn't work. It got worse.

After the bill was introduced, when I went home some people attacked me verbally. They said that I was a sinner, that I shouldn't be trusted with their daughters. Some bikers shouted at us, “We will screw your ass.” I don't have words to call that a bill. I call it horror, death. I ask myself if a human being drafted that shit. They pretend they fight for family tradition. But no human being can wish death or life imprisonment for another. How can you compare me to people who kill children? I just love women. If the bill passes, we will have to close our office. The landlord could be arrested, family, friends could be arrested. You can't go to anyone for help. People will start to kill themselves.

After 10, 20, 50 years, we will have a future. Like in America, there was a dream of a black president. And the dream came true. It took years. The world is moving forward. Uganda doesn't want to be left behind. Homosexuality is so African that colonialists set up laws against it. Why would they set up laws if there were no homosexuals? Homosexuals were already here. Homosexuality is everywhere.

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-009

I have a girlfriend who doesn't know, and a son. If she suspects, she doesn’t show it to me. She doesn't say anything even when I sleep out. I plan to tell her eventually. I am waiting for her to be financially independent. Then I will tell her, and even if she goes away, she can survive. I started with her when I was not sure of myself. I knew I was gay, but thought it was because I was not exposing myself to women. But the more I became bound to her, the more I realized I was gay. It is uncomfortable at home. She asks me why am I not sexually active with her, what's wrong with me. I lie that I have a low libido.

I have a boyfriend now. I can be absolutely sure I didn't learn this from anyone. I know I am this way naturally, since I was 7 or 8 years old. God understands. I know he created me this way, so why would he condemn me? A year ago I reconciled my sexuality and religion.

Our future is to continue living quietly underground. It will not be like, “Oh, look, there they are. Hello. Let them enjoy their lives.” Ugandan society is very traditional, religious, modest. There is no chance for gay pride in Kampala. We would be beaten. We're still a long way away.

20110316-znidarcic-mw18-collection-010

When I was in high school, girls used to write me letters, but I didn't understand what they wanted. I was dating men. Things happened when I was with men, but it wasn’t good. This was in me and it came out with my first girlfriend.

When I got engaged to her, it was in the papers. The engagement ceremony was by invitation, and one of the guests must have told the New Vision newspaper. The article made me a celebrity, but I lost friends, my employer. They ignored me. Nobody wanted to associate with me. Most of my friends know. At first, it was very hard for them to accept. Some of my friends don't want to hang out with me since they could be called lesbians.

I was in the papers so many times. They listed all the lesbians in Kampala and where they live. I get thrown out of many bars, so sometimes I don't go out. Sometimes men in bars say, “We will rape you, beat you, gang rape you until you become sensible.” It happens in bars when they want me, and I don't respond to them.

I want to live with my girlfriend, marry, and have a kid or two. With artificial insemination, I would carry her egg, so the child would look like her. She is butch, so she doesn't want to carry the egg.

Tadej Žnidarčič was born in Ljubljana, Slovenia, where he received a university degree in physics. He is a graduate of the International Center of Photography in New York City, where he was the recipient of the George and Joyce Moss Scholarship for Photojournalism in 2007. In addition to being a photographer, Žnidarčič is also a writer and videographer.

Žnidarčič received a 2007–2008 Global Fund for Children/International Center of Photography Fellowship, which took him to Bangladesh, India, and Romania to document the impact of local nonprofits on their communities. He has photographed polio victims in Nigeria, street children in Kenya, lead poisoning in camps for internally displaced people in Kosovo, and schools on boats in Bangladesh. He has documented the Nollywood film industry in Nigeria and worked with nonprofit organizations in health and education.

A contributing photographer for Redux Pictures, he has published in magazines, newspapers, and various publications in Africa, Europe, and the United States. In 2009, PDNedu ran a feature story on Žnidarčič, calling him “one to watch.” His work has appeared in solo and group exhibitions in Europe and the United States.

Tadej Žnidarčič

Homosexuality is not only stigmatized, but also illegal in Uganda. Publicly identifying as gay or being perceived as such can result in the loss of a job, arrest, harassment, blackmail, threats, and beatings. Antigay sentiment is widespread and many lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people hide their identity.

In October 2009, the Antihomosexuality Bill was introduced in the Ugandan parliament. Under the guise of protecting family values, it proposes life imprisonment for anyone engaged in homosexual activities and the death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality.” “Aggravated homosexuality” includes people who have gay sex more than once, homosexual activity by an adult with a person under 18 years old, or homosexual activity initiated by someone who is HIV positive. The bill also prohibits any production and dissemination of information related to homosexuality and prescribes jail time for anyone (including friends, parents, doctors, and priests) who fails to report homosexual activity to the authorities.

The bill was met with opposition from human rights groups, Western governments, and some religious leaders. Even Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has distanced himself from the bill, which remains sidelined in parliament and will probably not pass in its original form. Still, the bill has already encouraged increasing antigay behavior in an openly homophobic society that sees itself as setting an example for how the rest of the world should deal with homosexuality.

Reporting on the Antihomosexuality Bill in Ugandan and international media has largely focused on the creation, context, and consequences of the bill. Some LGBT activists working in Kampala were interviewed about their stories of struggle. Some agreed to be identified since they had already been outed in the Ugandan media, but the vast majority of people in the gay community do not want to be identified, and their stories remain untold.

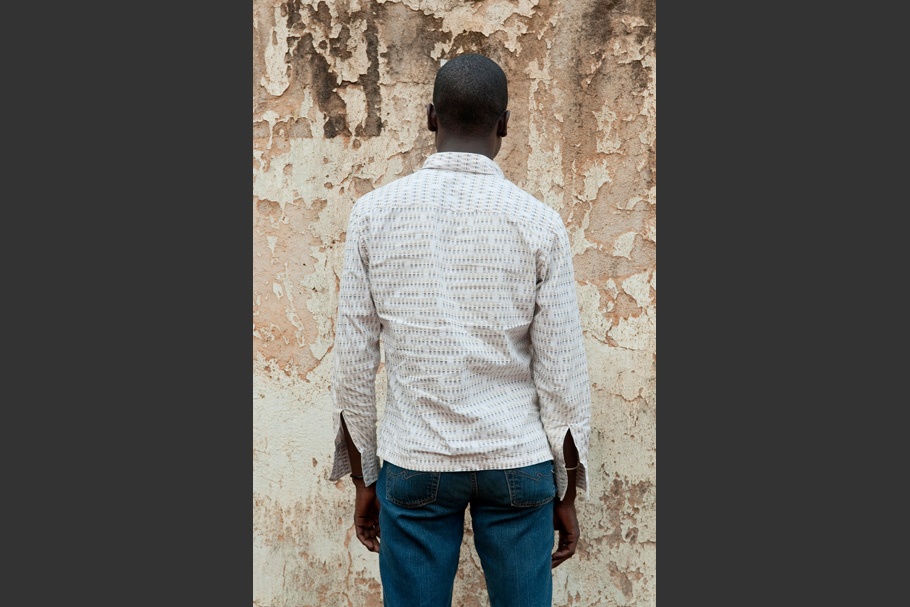

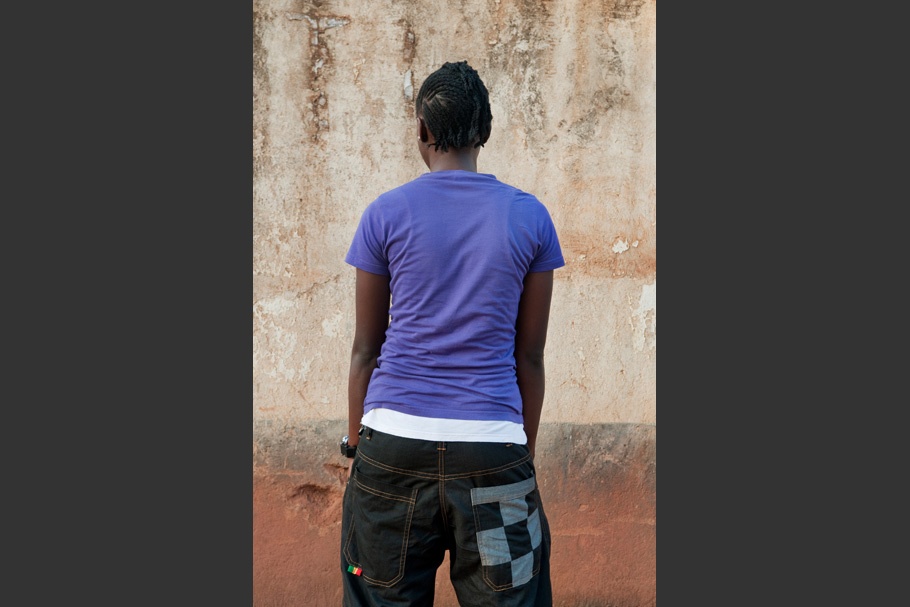

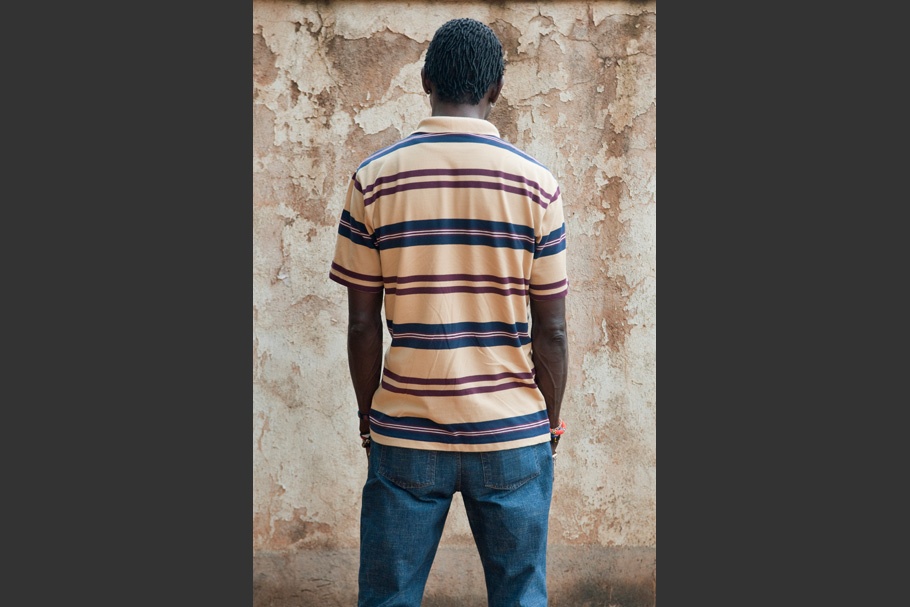

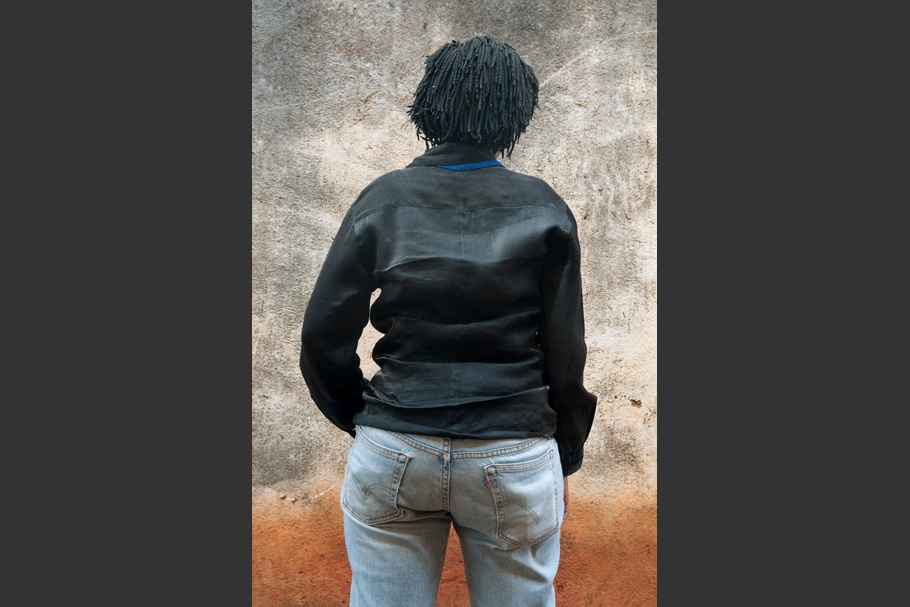

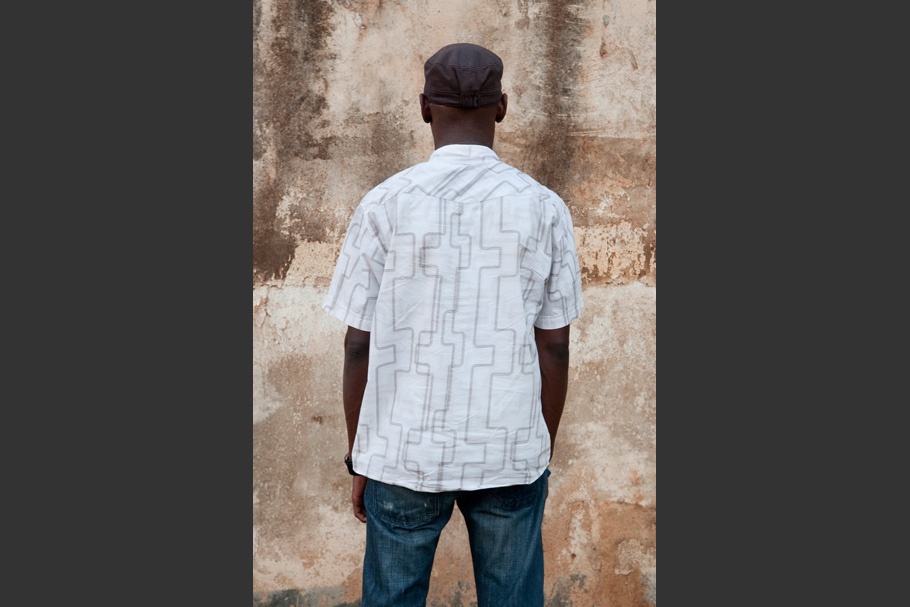

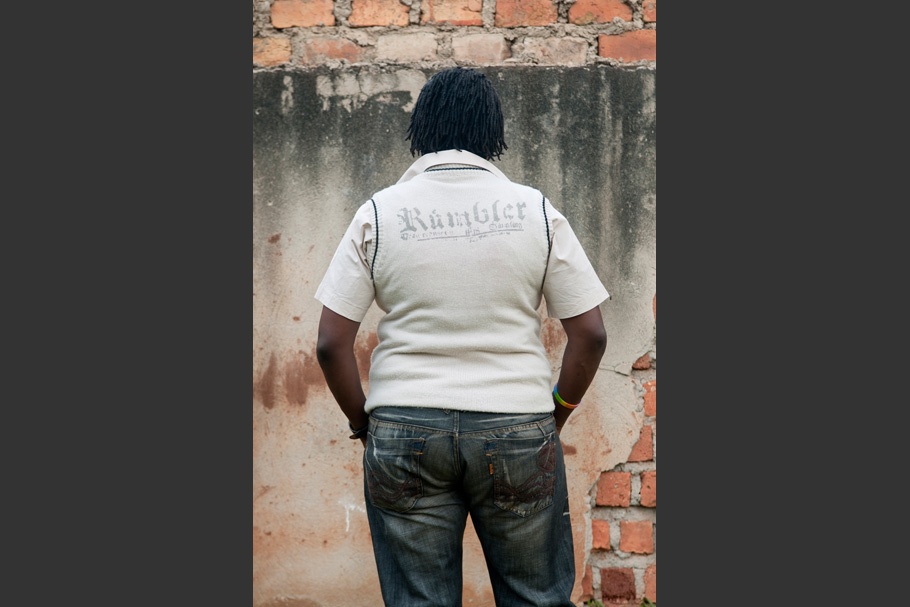

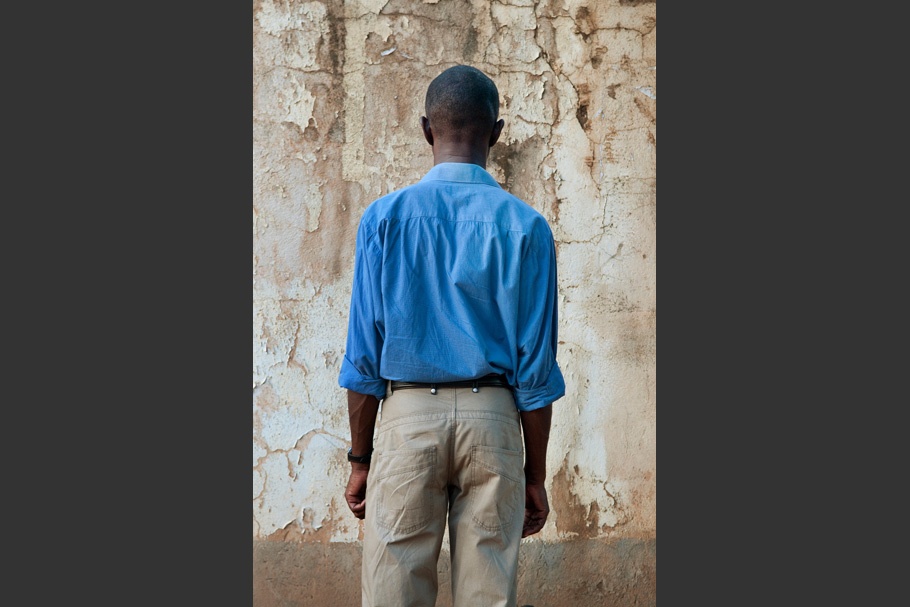

This project features LGBT people in Uganda, both activists and nonactivists, and presents their views on the proposed bill and homosexuality in African society, their personal stories of struggle against stigmatization and threats, and their hopes for the future. All of the people I spoke with wanted to remain anonymous. My challenge was to find a way to portray these men and women without compromising their safety, particularly since the Internet allows images and information to circulate freely and without control. After discussing the project with several activists and trying a number of options, I chose to photograph portraits of their backs. I wanted their posture and clothing to reveal their individuality, while the walls against which they were photographed symbolize the obstacles they face and their exclusion from society.

—Tadej Žnidarčič, November 2011