20110316-box-mw18-collection-001

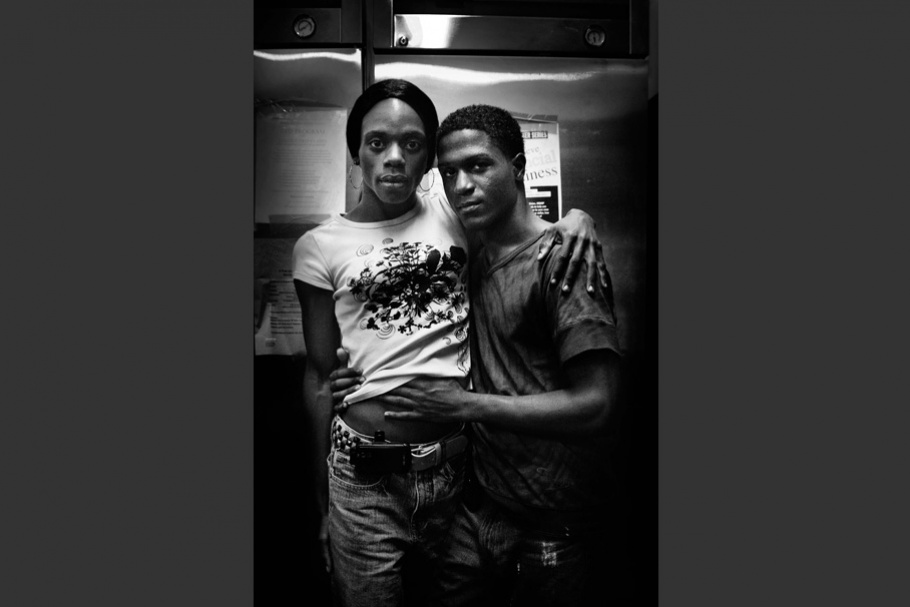

Matthew and his girlfriend, during drop-in hours at Sylvia's Place.

September 2008

20110316-box-mw18-collection-002

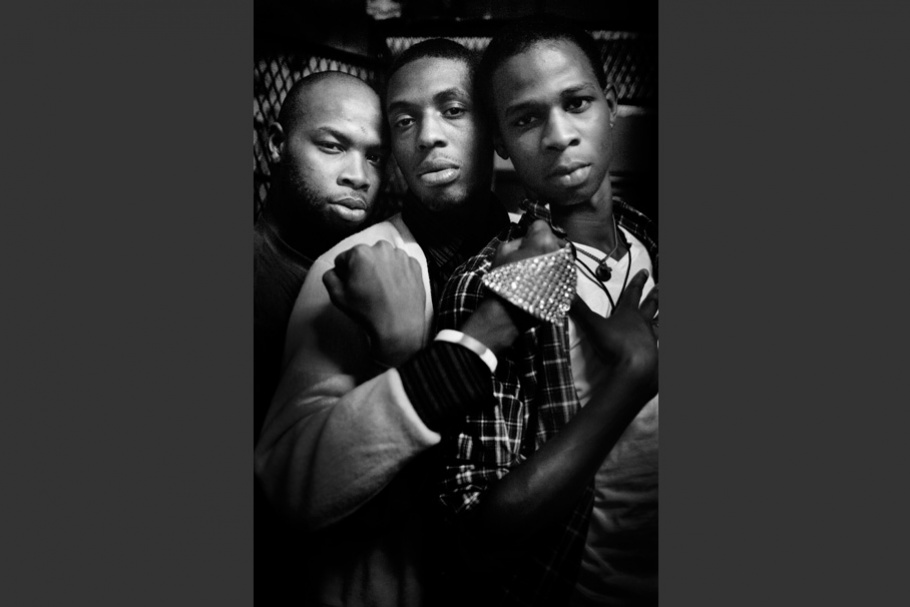

Bama, Omar, and Devin, friends, during drop-in hours at Sylvia's Place.

November 2008

20110316-box-mw18-collection-003

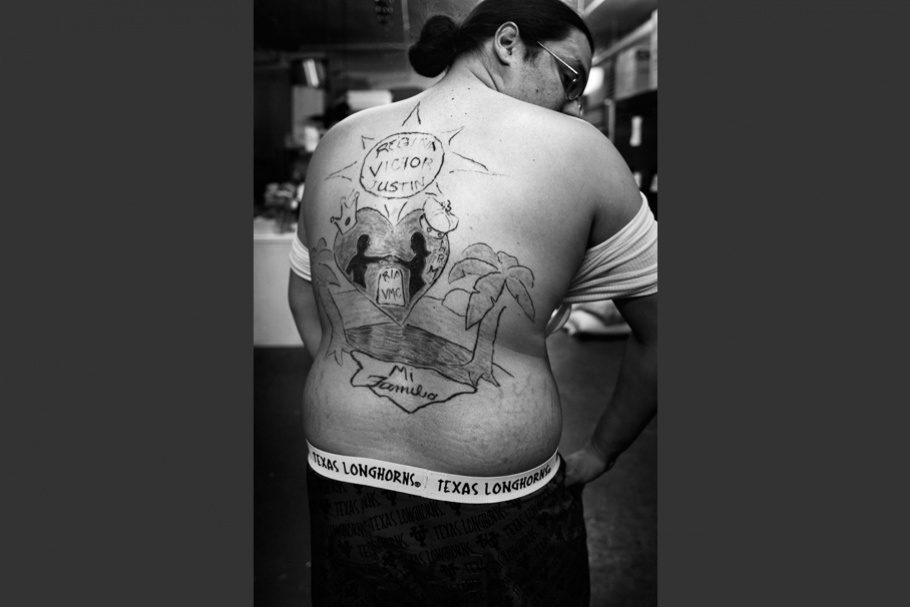

Dilo's tattoo, created while he was in juvenile prison, commemorates his estranged family.

Many homeless LGBT youth have had brushes with the law. Without a family to support them, homeless LGBT youth have difficulty being considered for alternatives to incarceration that can give a domiciled youth with a minor charge a second chance.

December 2005

20110316-box-mw18-collection-004

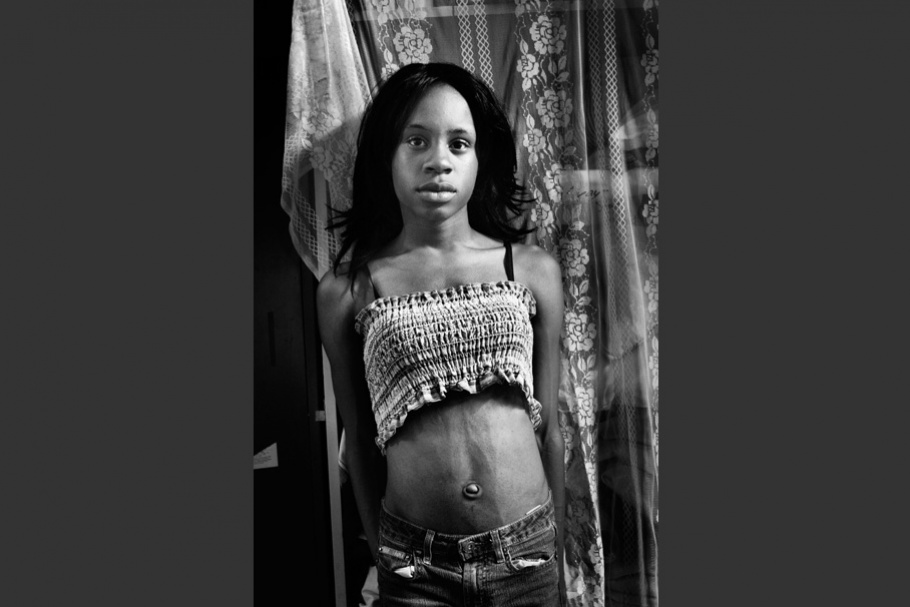

Isyss, a young transwoman, poses for a picture during drop-in hours at Sylvia's Place. This picture was taken during her first week in New York City. Isyss left her mother's home in Georgia after encountering extreme transphobia in the community where she was raised.

July 2006

20110316-box-mw18-collection-005

Isyss and her girlfriend Q hang out with Jasmina and Kailah in front of the shelter's entrance after drop-in hours.

October 2006

20110316-box-mw18-collection-006

Misty and Keith kiss under the shelter's holiday decorations.

Many of the staff of Sylvia's Place were themselves homeless young people, and can relate to the struggles of their clients. Special efforts are made at holidays and on birthdays, events that can trigger feelings of loss, anger, and sadness over not being with their biological families.

January 2006

20110316-box-mw18-collection-007

Cocco watches over her sick girlfriend, Melissa, while trying to battle her own exhaustion, during drop-in hours at Sylvia's Place.

December 2006

20110316-box-mw18-collection-008

Sylvia's Place is housed in the basement of the Metropolitan Community Church of New York and shares the space with the church's food pantry. The young residents sleep wherever they can after drop-in services are finished for the evening.

February 2010

20110316-box-mw18-collection-009

Sylvia's Place.

June 2006

20110316-box-mw18-collection-010

Sylvia's Place.

May 2006

20110316-box-mw18-collection-011

Meisha vogues during drop-in hours at Sylvia's Place.

March 2010

20110316-box-mw18-collection-012

Even though many of the youth are estranged from their families, they hold on to memories. Here, a client of Sylvia's Place shows a staff member a prized family photo.

September 2006

20110316-box-mw18-collection-013

Cocco visits her mother's grave. Her mother's death forced Cocco into the foster care system, which was traumatizing, and from which she fled, seeking safety in the streets.

Thirty percent of all LGBT homeless youth have had experience in the foster care system, which, by many accounts, is a very anti-LGBT environment or, in some cases, violence at the hands of staff members or foster parents.

May 2007

20110316-box-mw18-collection-014

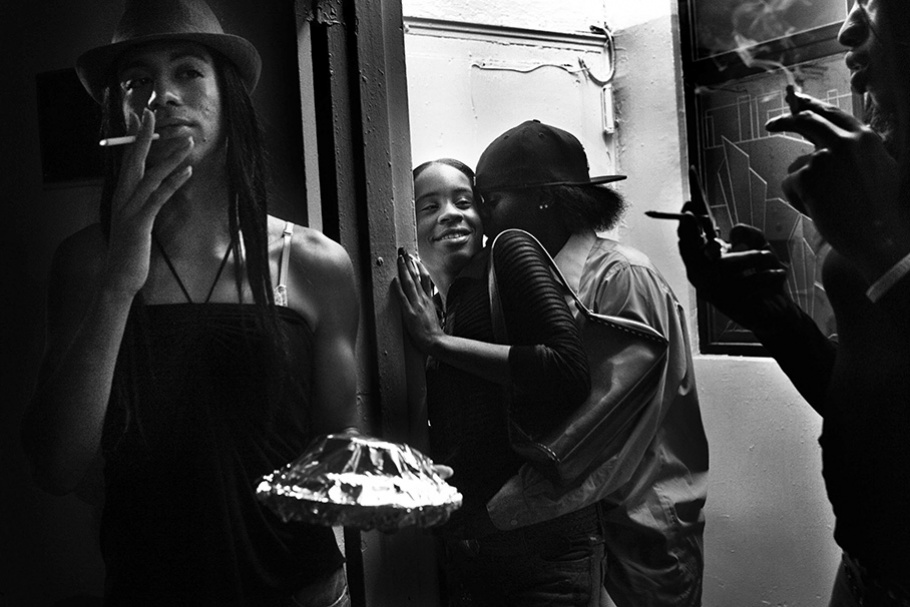

Jaida and Alex, "sister" and "brother," smoke their last cigarettes before lights-out at Sylvia's Place.

Estranged from their biological families, these young people create new families for support and protection, acting as fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers, and aunts to each other.

October 2007

20110316-box-mw18-collection-015

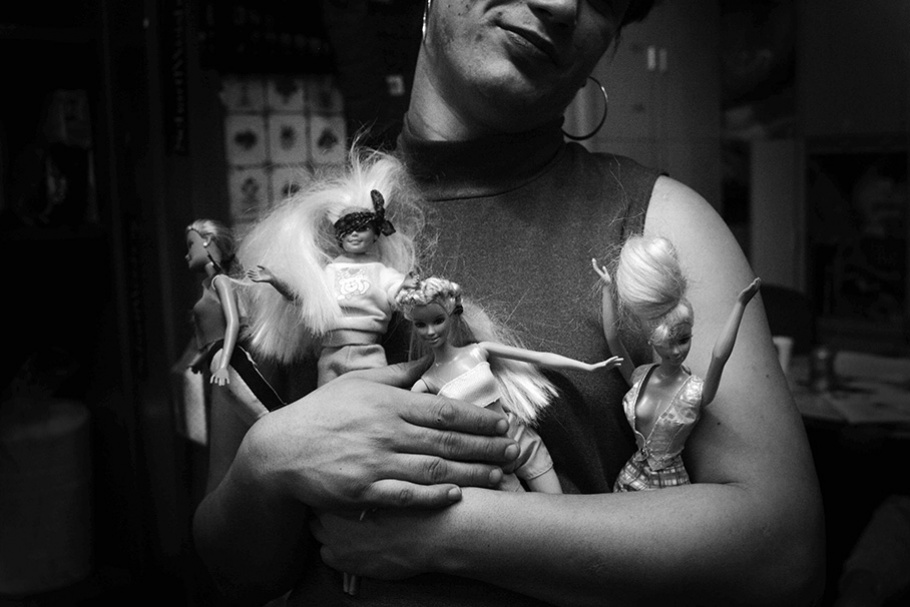

Josephine holds Dilo's Barbie doll family during drop-in hours at Sylvia's Place.

January 2006

20110316-box-mw18-collection-016

Jasmina, on "the stroll" in the West Village neighborhood of New York.

Transgender people are a high proportion of homeless LGBT youth--and generally the most marginalized. Because of their gender-nonconforming identity, they are often turned away from the few social services available to homeless, lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. For example, they are denied access to shelters that segregate clients based on birth sex. Transphobia and the lack of appropriate identification reflecting their chosen name and gender (which requires access to legal medical services and money to pay for state agency fees) makes it hard for many young transpeople to find a legal job, leaving sex work as one of the few options.

March 2007

20110316-box-mw18-collection-017

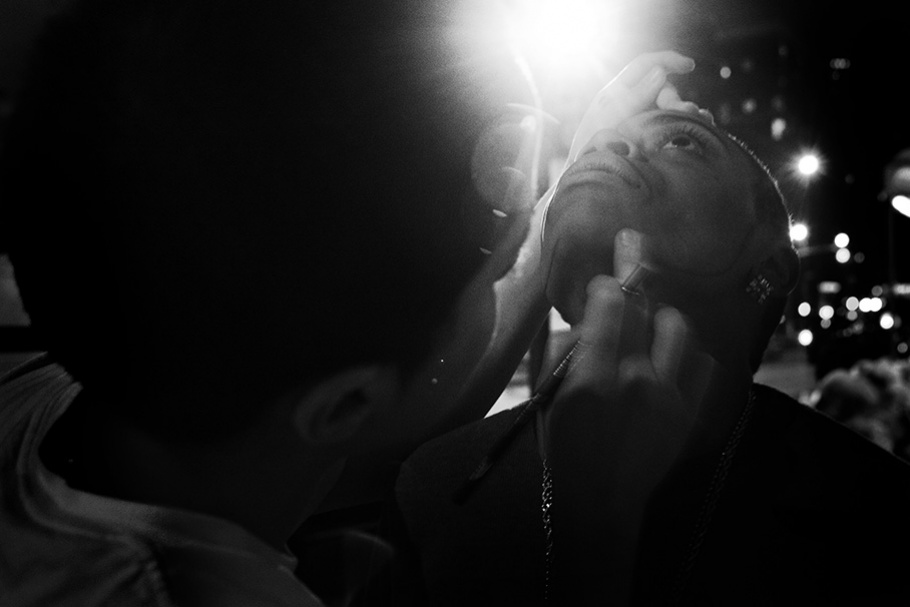

Cocco draws a beard on Sharon's jawline at Sylvia's Place.

April 2007

Based in New York City, Samantha Box was born in Kingston, Jamaica. After working for many years in the media—first at the New York Post, and later at Contact Press Images, an international photojournalism agency—she attended the International Center of Photography in 2005, where she pursued a certificate in photojournalism and documentary studies.

For the past four years, she has dedicated herself to photographing homeless lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth in New York City. Her project, Invisible: The Crisis of LGBT Youth Homelessness, has been recognized by the Anthropographia Award for Photography and Human Rights, En Foco, and the New York Foundation for the Arts. The work has been published in Kicked Out (an anthology of essays by current and former LGBT youth) and the online publications 100 Eyes and The Raw File. The work was exhibited in 2010 at The Sanctuary for Independent Media in Troy, New York.

Samantha Box

According to the U.S. government, the number of homeless and runaway youth ranges from 575,000 to 1.6 million. Out of that number, it is conservatively estimated that between 20 and 40 percent identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), widely considered to be the fastest-growing demographic in the homeless youth population.

Many homeless LGBT youth are people of color and come from low-income families. Many come from homes marred by instability, conflict, abuse, neglect, or parental drug use. Many are forced to leave their homes: often family members assault them and kick them out when they reveal their sexual orientation or gender identity. Having experienced this violent rejection at home, in church, at school, or, in some cases, in foster care, these abandoned youth turn to the streets. Too often, sex work, survival crime, drug abuse, and untreated mental illness become a part of everyday life. Animosity toward LGBT youth’s sexual orientation or gender expression at mainstream shelters and programs effectively bars them from receiving the meager services available to homeless youth, services that might move them toward more stable lives. By being homeless in a society that discriminates against LGBT people, these young people are rejected twice: first by their families and communities, and again by the service providers and shelters that are supposed to help and protect them.

In 2005, disturbed by the silence surrounding this issue and seeking to put a face to this crisis, I began photographing the residents of Sylvia’s Place, New York City’s only emergency shelter for homeless LGBT youth. Its 30 beds comprise over half of the beds (the others are in mixed shelters) specifically designated for the upwards of 8,000 homeless young LGBT people in the city. Using the shelter as a home base, I spent countless hours—both inside and outside the shelter walls—as a witness to intimate moments often hidden from public view: crying at the grave of a mother who left too soon; kissing a new boyfriend; sharing moments of tenderness with members of one’s chosen family.

As this project continues, it is my hope that this work will not only bring awareness to the crisis of LGBT youth homelessness, but also draw attention to the support networks and sense of community that shelters such as Sylvia’s Place can create.

—Samantha Box, November 2011