20031016-peru-mw08-collection-001

On September 24, 1992, Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmán was allowed to make a public appearance while in the custody of DINCOTE, the government’s antiterrorism task force. In front of more than 100 domestic and foreign journalists, Guzmán gave a speech and sang the Internationale, the Communist anthem.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-002

As part of the government’s Civic Action campaign, soldiers gave lessons on Peru’s patriotic symbols to a group of children in the Huaycán encampment in Lima.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-003

Alleged rebels were transferred to El Fronton, a penal island off Lima, in March 1982.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-004

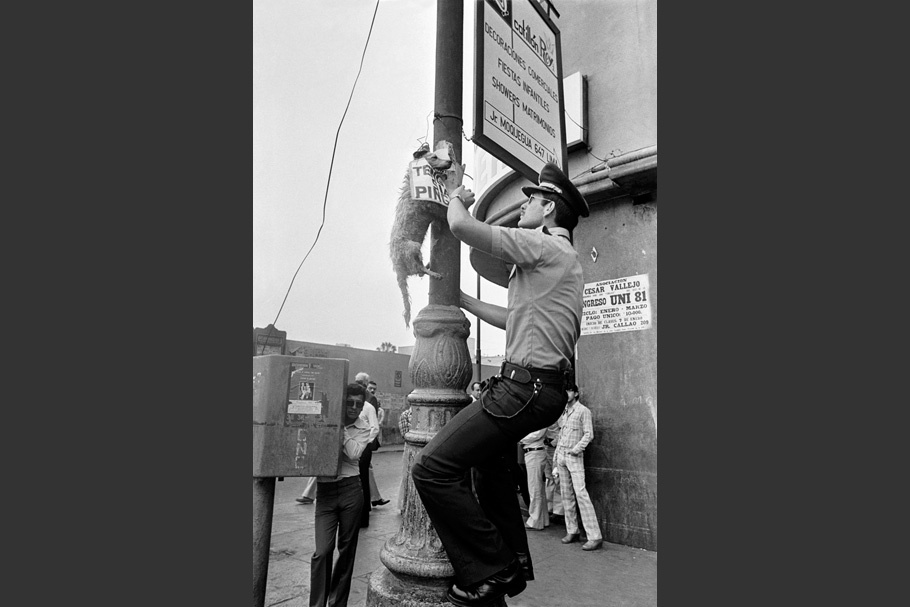

On December 26, 1980, members of the Shining Path rebel group announced its formation by hanging dead dogs from lampposts in downtown Lima. The signs around the dogs' necks can be translated as "son of a bitch."

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-005

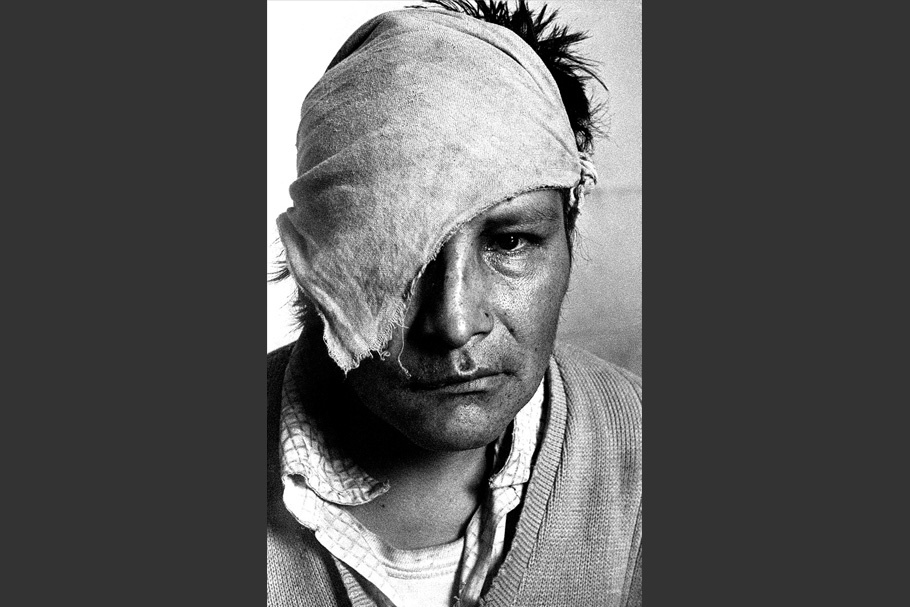

At the Ayacucho Regional Hospital in 1983, Celestino Ccente, a peasant from Iquicha, Huanta, recovered from wounds inflicted by Shining Path guerillas.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-006

A young Ayacucho rondero—a local farmer fighting against the rebels—held up a Shining Path flag as a trophy in 1991.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-007

A March for Peace was held on November 3, 1989, in opposition to an armed strike decreed by Shining Path.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-008

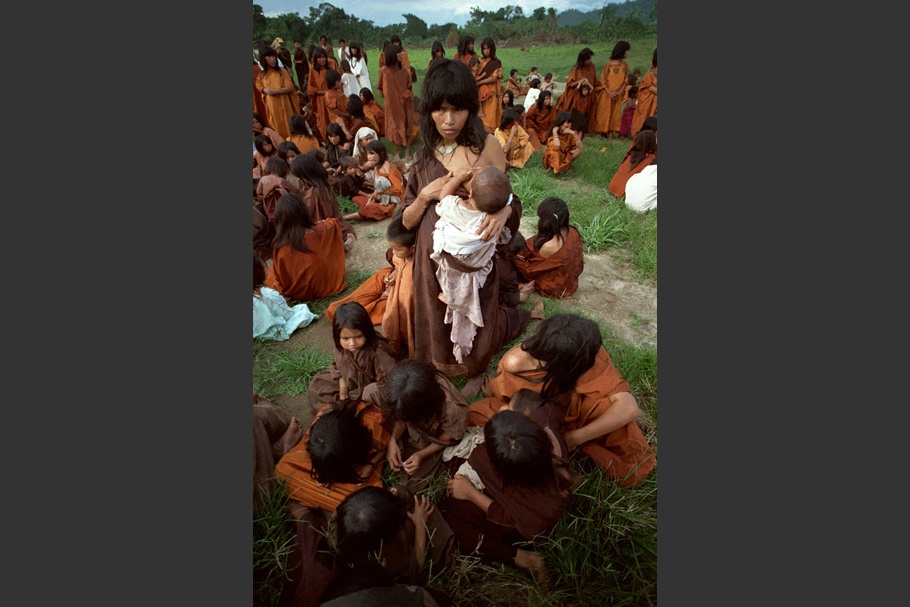

Ashaninka women freed from a rebel camp wait for food from the government in Cutivireni, Junon, 1991.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-009

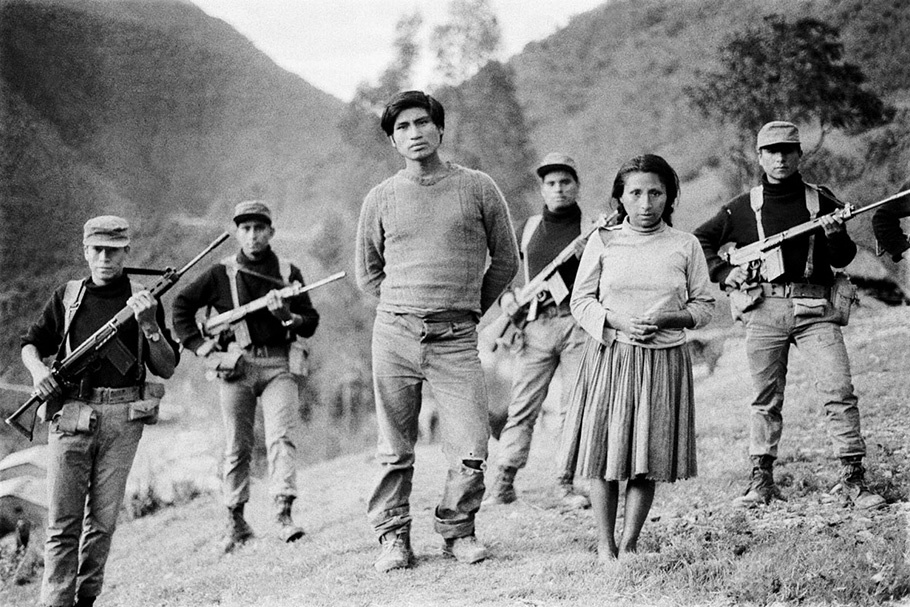

In Lar Mar, Ayacucho, in June 1985, soldiers stood with Ramon Laura Yauly and his wife, Concepcion Lahuana, who said they had been forced to join Shining Path against their will.

Photograph appeared in Caretas magazine.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-010

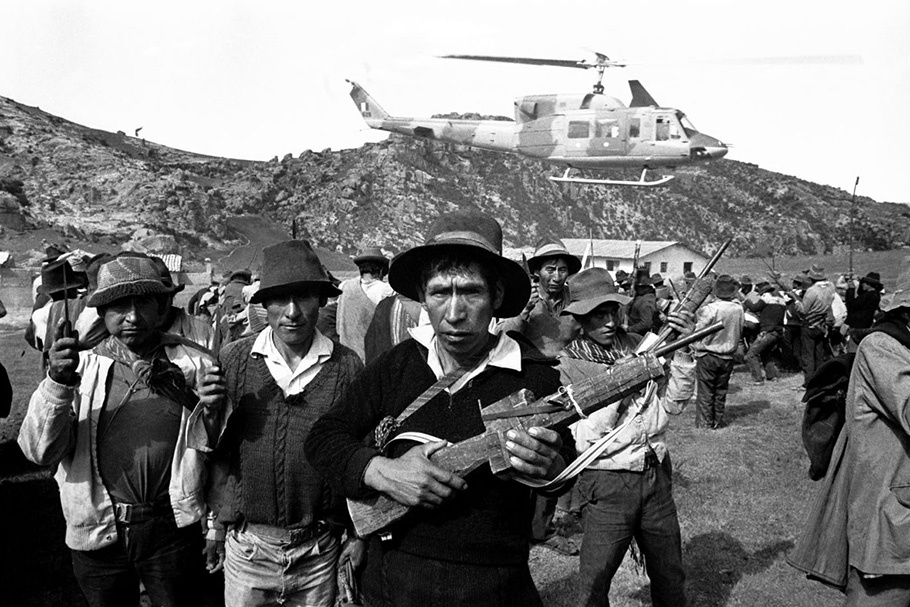

After a rebel massacre in April 1990, villagers in Chuppac, Huancavelica, formed a rondas campesinas—a peasant defense unit supported by the army.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-011

A woman carried her belongings to a secure place after Shining Path’s attack on Calle Tarata, Lima, in July 1992.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-012

In August 1984, 50 corpses, with evident signs of torture, were found in mass graves in Pucayacu, Huancavelica. Further investigation found that the government forces in control of Huanta, Ayacucho were responsible for the deaths.

Photograph from Caretas magazine.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-013

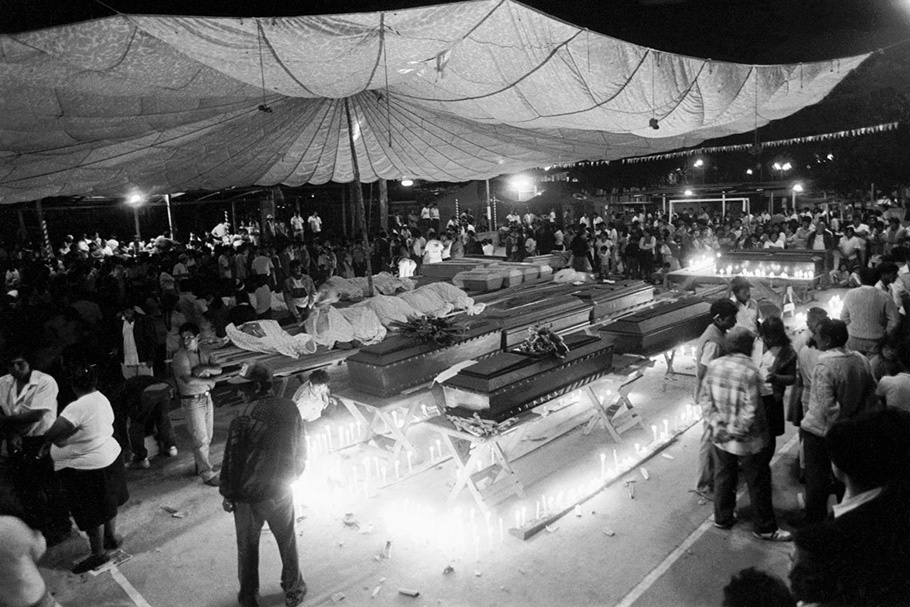

A funeral was held on August 20, 1993 for the 65 victims of a rebel massacre in Valle de Tsiriari, Junín two days earlier.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-014

A policeman was buried after being killed in Lima during a Shining Path raid in 1984.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-015

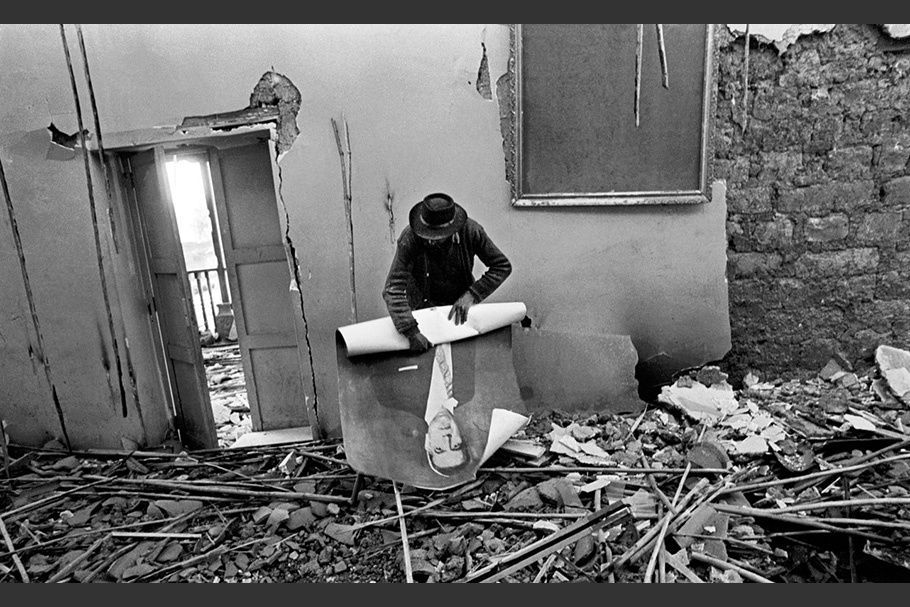

A portrait of President Belaunde was recovered from the rubble after Shining Path’s August 1982 attack on City Hall in Vilcashuaman, Ayacucho.

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-016

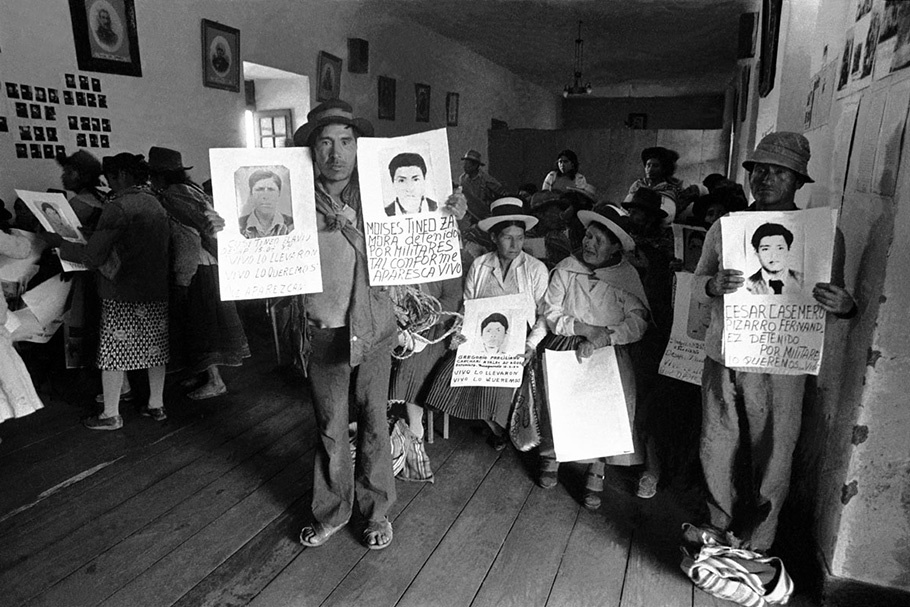

In July 1985, relatives of missing people gave testimony before the European Human Rights Commission at City Hall in Huamanga, Ayacucho.

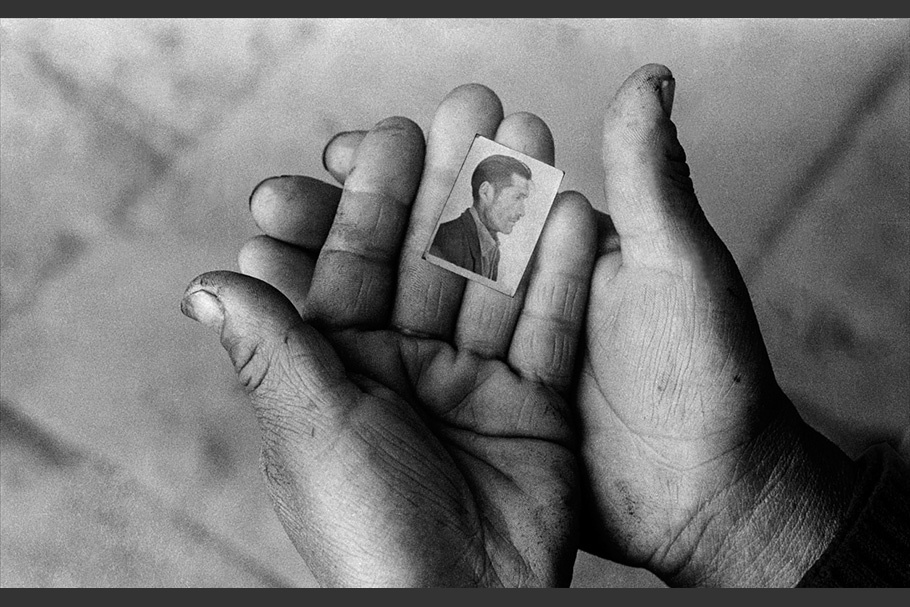

20031016-peru-mw08-collection-017

A woman held a photograph of a family member who vanished from the province of Ayacucho.

Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was created to investigate what happened during the years 1980 to 2000, when Peru endured an internal conflict between government and opposing forces that left as many as 60,000 people dead or disappeared. In the Supreme Decree number 065-2001-PCM, the state declared these objectives for the TRC: determine the causes of the violence in Peru between May 1980 and November 2000, contribute to the investigation of the crimes and human rights violations perpetrated during that period, identify, when possible, the perpetrators responsible for these violent acts, elaborate proposals to make reparations to the victims and their families, recommend the implementation of reforms as preventive measures, and establish follow-up mechanisms for these recommendations.

Peru's Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Among the many painful choices that every postconflict community must make, one in particular is both unavoidable and necessary: to remember or to forget. In forming a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Peru has chosen to remember. It has thereby opted for truth. It is a moral decision that requires courage and maturity.

In coming to terms with two decades of violence, Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s underlying task has been the search for facts, information, and evidence, and the connections between them. The images shown here represent a part of the truth we were charged to recover.

Our responsibility was to offer the country a portrait of itself, to reconstruct the experiences of the victims of the violence. The images selected for this exhibition come from a bank of 1,725 photographs belonging to more than 90 photographic archives. They capture the events that occurred between 1980 and 2000, and attempt to create a visual narrative of a period that caused the deaths or forced disappearance of as many as 60,000 people.

These photographs document the resistance of thousands of men and women in terrible circumstances. The desolation and perplexity written on their faces is the most powerful testimony about Peru’s tragedy. At the same time the photographs give us an urgent mandate: to ensure that the past is never forgotten, either on purpose or through indifference. And it compels us to write our recent history with an understanding of the causes, integrating into this knowledge the memory of those who suffered in silence.

By showing these images, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission wishes to acknowledge those professionals, who in spite of the heat of the violence looked at the victims with eyes of compassion and solidarity. The Commission is also offering all Peruvians the visual evidence of a history that we must not only understand, but also identify as our own. Only then can we build a more peaceful and humane country.

—Salomón Lerner Febres, President, Truth and Reconciliation Commission, October 2003