20031016-liss-mw08-collection-001

Young inmates march through the prison yard at dawn. After waking up at 4:45 a.m., they begin each day with an hour of physical activity.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-002

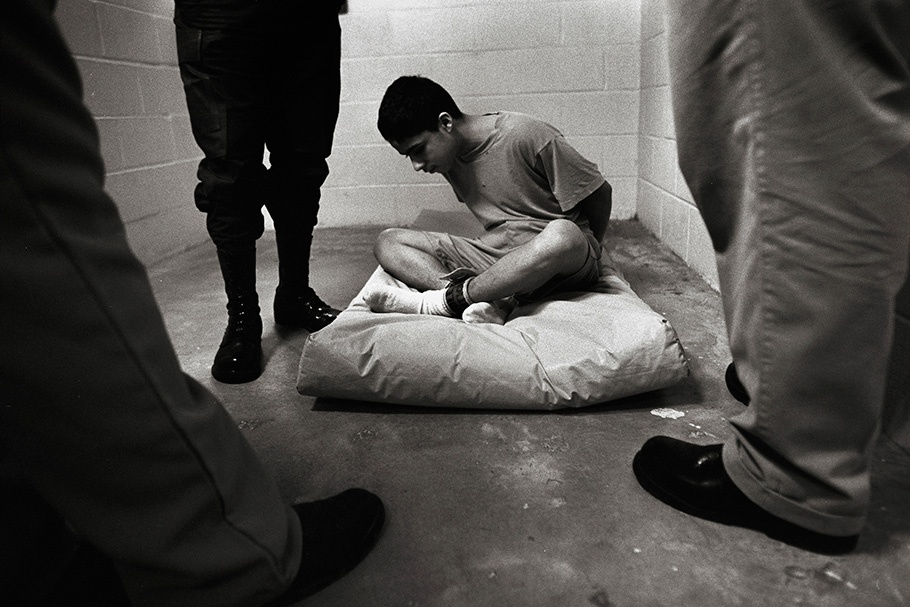

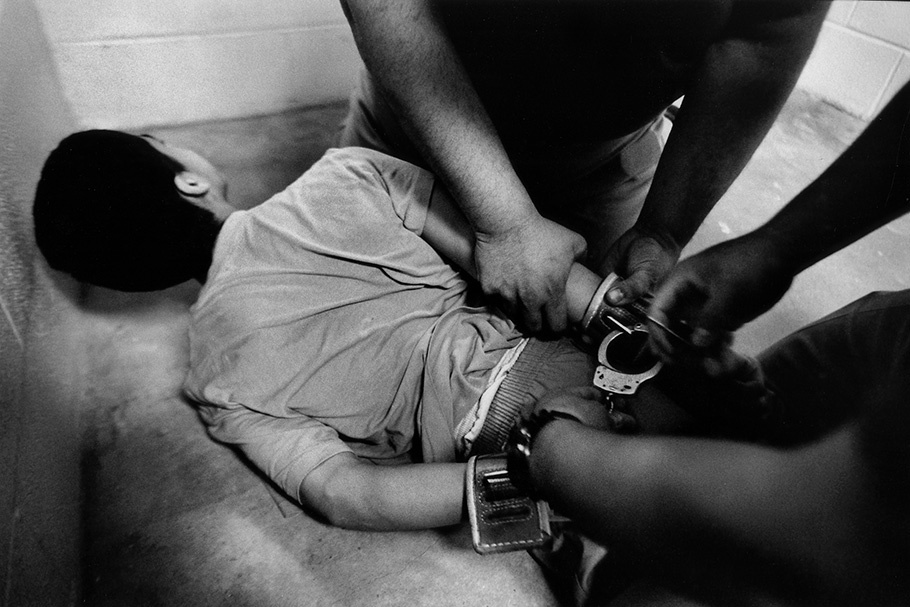

While a child is restrained, he is under the constant supervision of at least one detention officer. Though most children in detention do not need to be restrained, others, particularly those under the influence of drugs, may be restrained several times during a single day.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-003

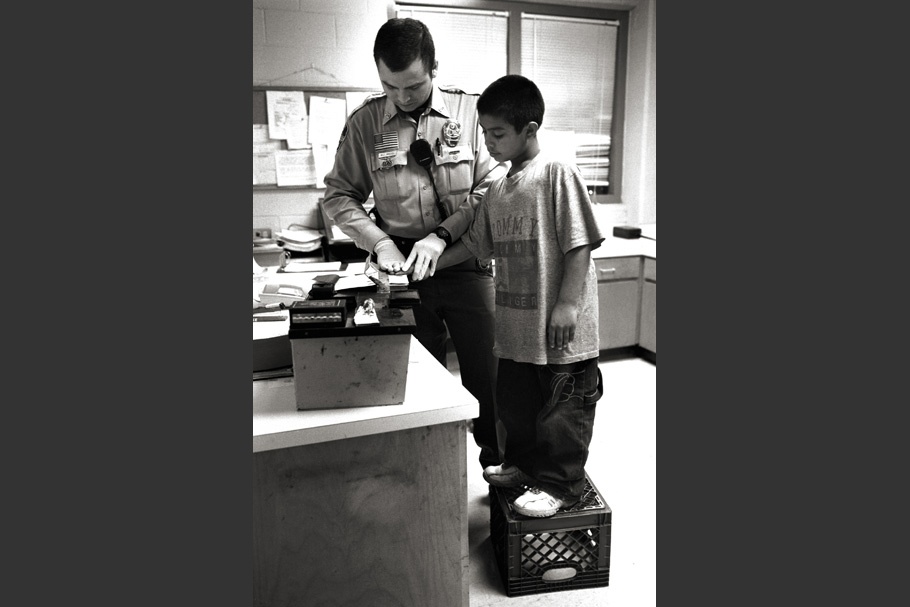

Alejandro, a 10-year-old boy charged with possession of marijuana, stands on a milk crate to be fingerprinted. "Every day the offenders get younger, smaller, less conscious of their actions," says Adam Rodriguez, a Webb County juvenile probation officer. "It's like an infection that's starting to drop into the elementary schools."

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-004

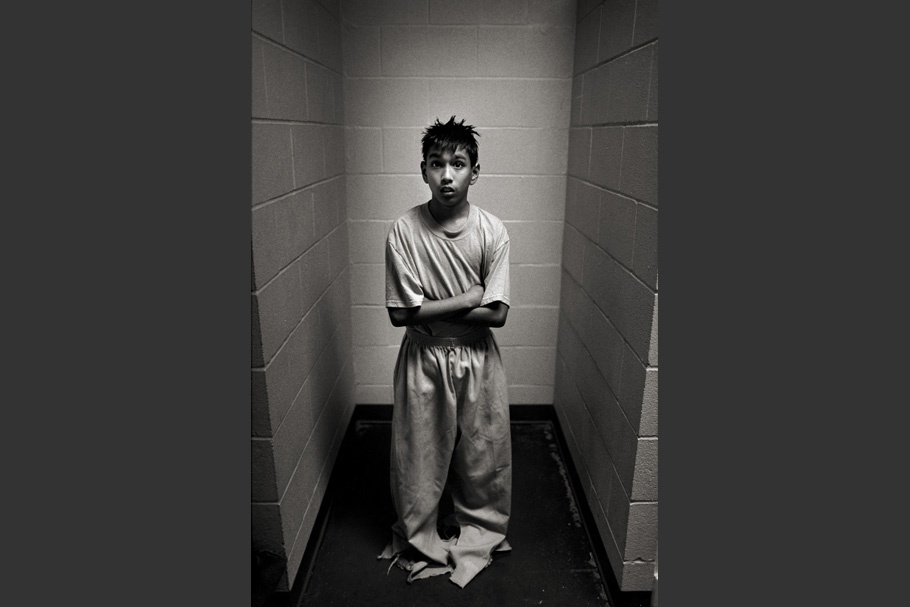

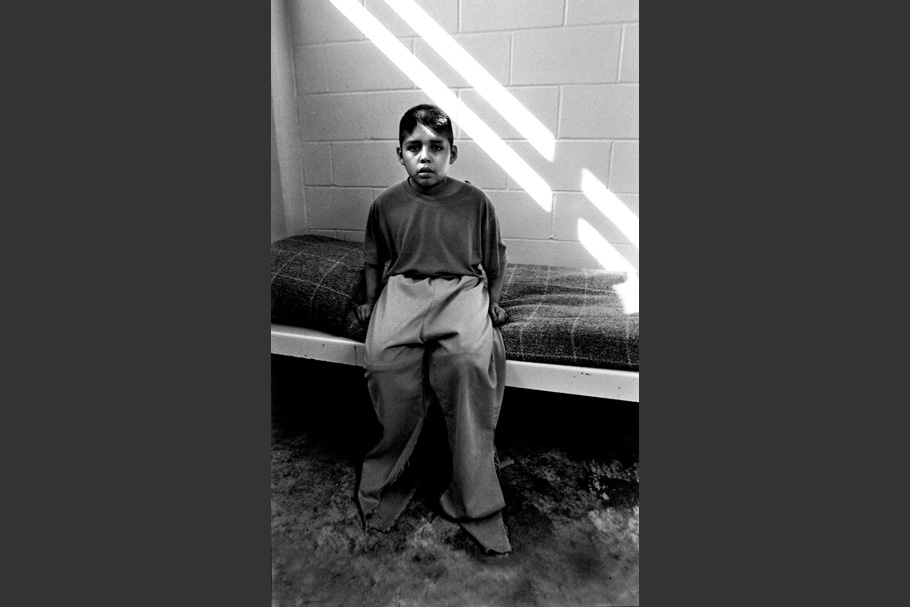

An 11-year-old boy is placed in detention for the first time after being arrested for shoplifting. With few alternatives available, children as young as 10 are detained at the Webb County facility.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-005

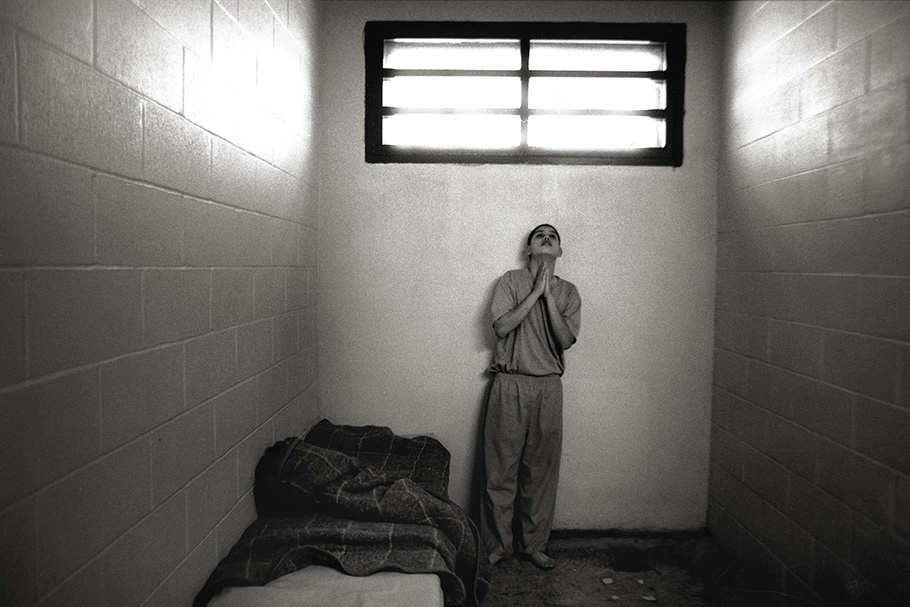

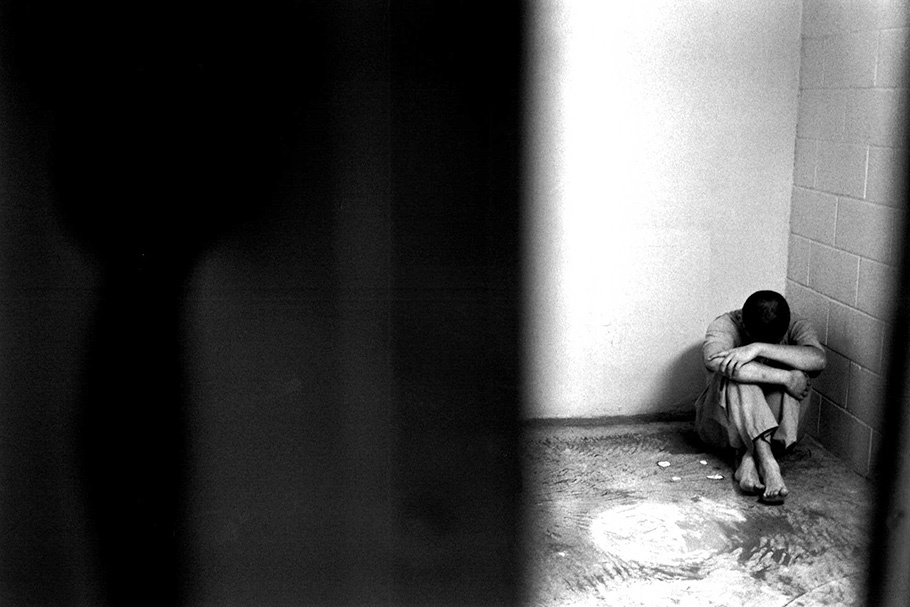

Rolando prays alone in his cell. The 15-year-old was given 24 hours of cell confinement as punishment for "failure to comply"—in this case for disobeying staff orders to make his bed in the morning.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-006

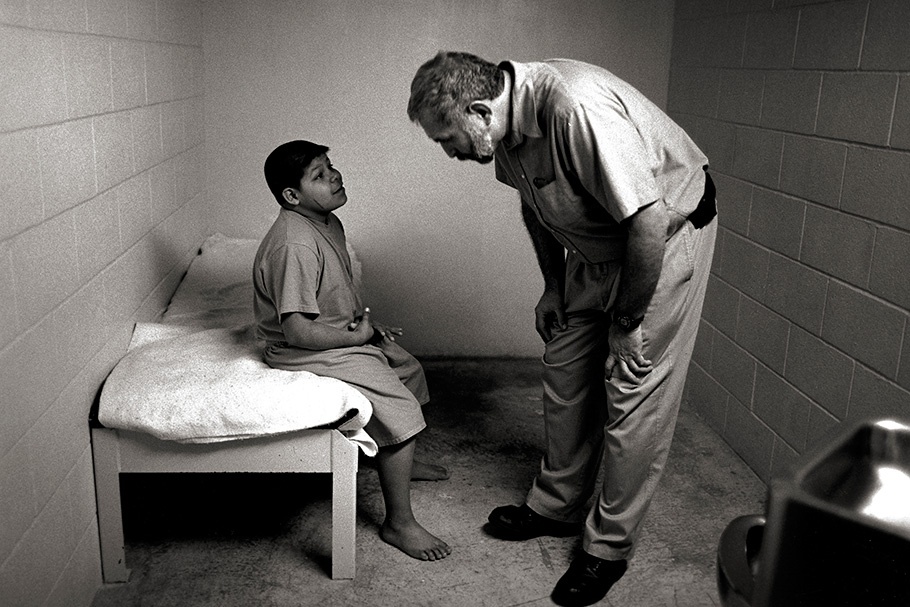

A lot of these kids are just angry. “I try to hug them”, says probation officer Adam Rodriguez. “They don’t know how to hug.”

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-007

A lot of these kids are just angry. “I try to hug them,” says probation officer Adam Rodriguez. “They don’t know how to hug.”

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-008

If a child is considered an imminent threat to himself or others, he is physically restrained—with handcuffs and manacles—until the staff thinks the crisis has passed.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-009

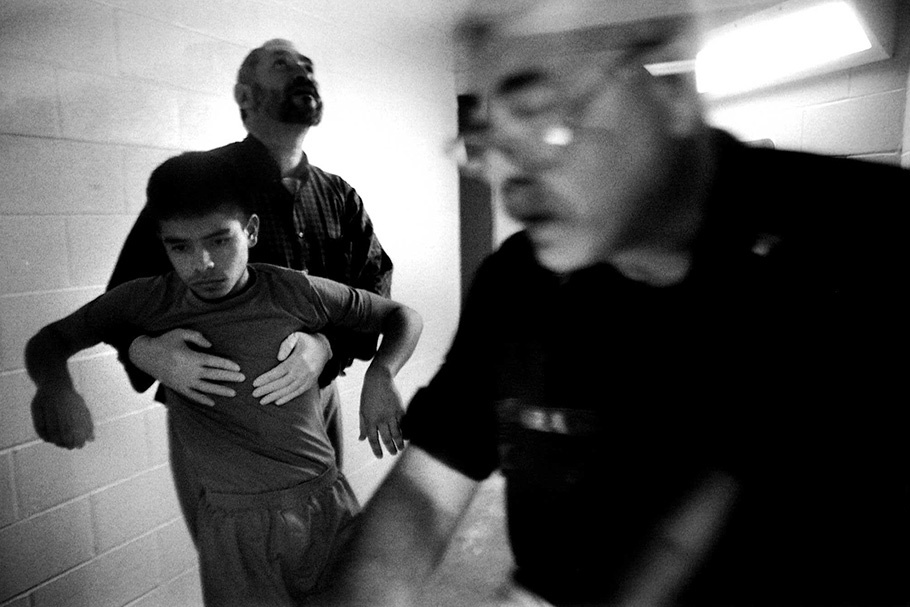

Leo Delagarza supports Rene, who is still detoxing and incoherent, while Sergeant Lara searches his cell, looking for homemade weapons. Nothing was found.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-010

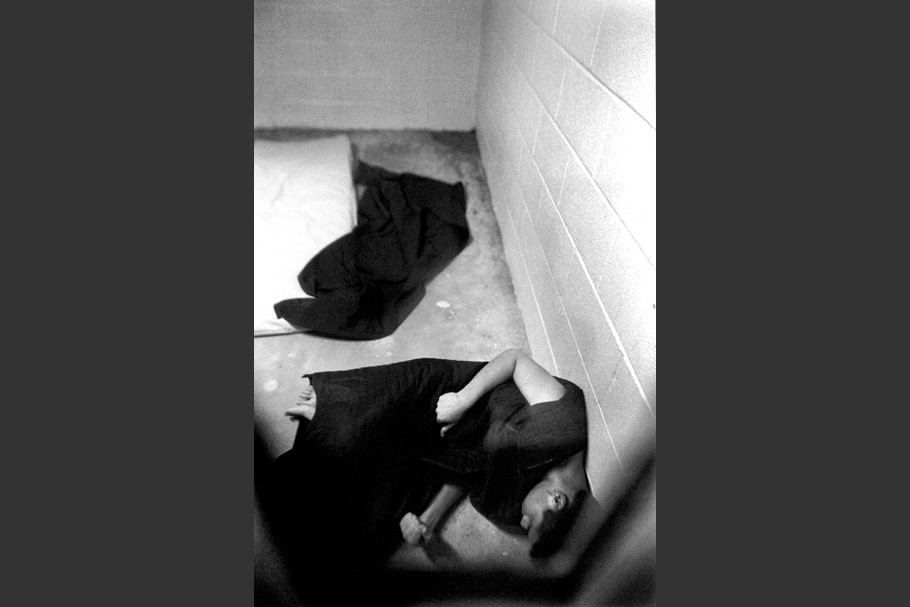

Rene lies on the floor of his cell passed out after several days of sniffing carburetor fluid. The garment that he wears was designed to protect detainees from harming themselves.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-011

Christian, 10 years old, stabbed his 12-year-old brother with a kitchen knife. In Laredo, as in other communities, family violence accounts for a significant number of detained juveniles. Christian spent nine days in detention before being released to his parents.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-012

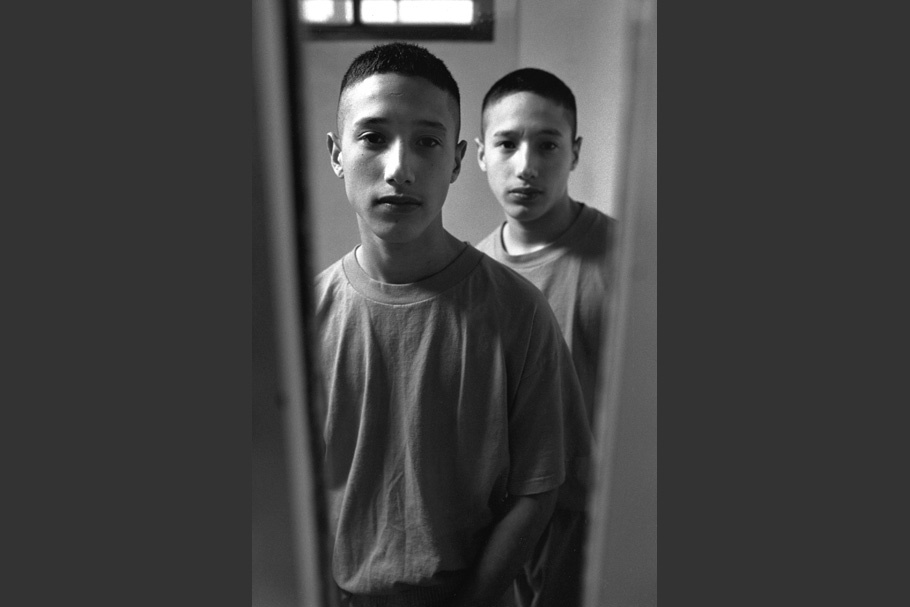

Fourteen-year-old twins Jose Eduardo and Jose Hernandez were both incarcerated at the same time for different crimes. Jose (right) is charged with the more serious crime of aggravated assault. He pled innocent at his hearing and, partially due to delays in the trial process, is beginning his fourth month in detention.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-013

After years of working at the detention facility, guard Leo Delagarcia approaches each child and situation differently; although he can be a strict disciplinarian, more often he is patient and fatherly.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-014

After several days of sniffing carburetor fluid, 16-year-old Rene detoxes in an isolation cell. Laredo used to have a detox facility specifically for children and the local hospital had an adolescent psychiatric unit; both were closed due to lack of funding.

20031016-liss-mw08-collection-015

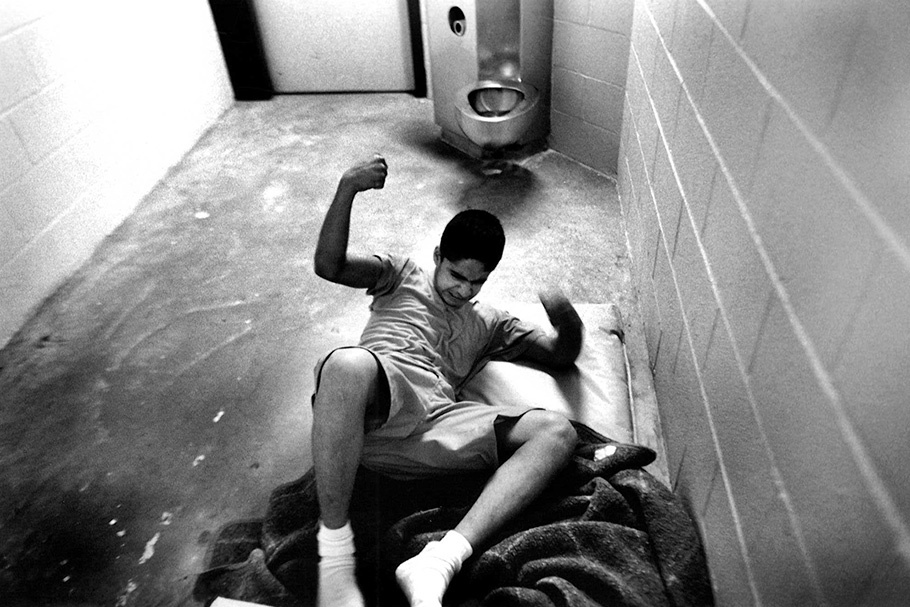

Hours after being arrested for cocaine possession, 15-year-old Rolando sits on the floor of his cell.

Steve Liss, a native of Quincy, Massachusetts, has been a news photographer since the age of 17 when he began taking pictures for his hometown weekly newspaper, The Quincy Sun. He has been photographing the United States for Time since 1976.

Though Liss has covered six presidential campaigns, his greatest satisfaction comes from exploring themes of social significance through photographs of everyday life. Thirty-seven of his photographs have appeared on the cover of Time, and he has won numerous awards from the National Press Photographer’s Association, Pictures of the Year, and the World Press Association, including First Place: Magazine Picture Story in 1996 and First Place: Magazine Feature in 2003.

Steve Liss

“I’m 16 years old and I have nothing to be proud of.” So begins Aurelio Dominguez’s candid disclosure, recorded in his cell at the juvenile detention facility in Laredo, Texas.

This is the stuff of juvenile delinquency, of kids gone astray, of child inmates who cry for their mothers from behind bars. Some have skipped class too much, some have murdered in cold blood. At least half of these kids have been incarcerated before and, if institutional rehabilitation is inadequate or ultimately fails, if parents do not do anything to turn around years of neglect and abuse, a few more visits to juvenile detention will harden many of them into full-fledged, adult criminals.

Nationally, nearly two million youth under the age of 18 are arrested each year and more than 130,000 spend time in juvenile or adult corrections facilities. Although most juvenile offenders are not violent, state legislatures have overwhelmingly responded to short-lived increases in juvenile crime during the late 1980s and early 1990s by moving away from rehabilitative approaches toward more punitive remedies for juvenile offenders. Since 1992, 47 states and the District of Columbia have made their juvenile justice systems more punitive.

These photographs represent six months of work documenting the lives of children incarcerated in the juvenile detention facility in Laredo. Here, as in similar facilities throughout the United States, young offenders aged 10-16, many suffering from mental illness and drug dependencies, are locked up, sometimes for weeks or months, waiting for trial or placement. Overcrowded and underresourced detention facilities were never designed to meet the needs of these children, but in Laredo, as in other jurisdictions nationwide, that is exactly what they are being asked to do.

“These are the least favorite kids in America,” said one children’s advocate. Yet these kids, for whom drugs, violence, and crime are part of daily life, want to be understood and need the chance to tell their stories. For many, nothing in their lives—not school, not home, not human relationships—has been positive or satisfying. Though they cope by doing the best they know how, most are ready to give up by the age of 12 or 14.

Yet beneath their despair and anger, these young offenders are just children, many of them intelligent and likable. While working on this project, I often had to fight the temptation to befriend them because I knew I would soon be leaving town—just one more adult walking out on them. This was particularly difficult because, even in the brief time I spent with them, I saw moments of promise. I believe that, like all children, they have the potential to change and grow.

Throughout my career I have been deeply concerned with youth, a commitment that shapes the way I approach my work and life. In giving a human face to the statistics on juvenile crime, I hope these photographs will challenge us to see these children not as a social ill, but rather a social responsibility. And by providing a glimpse into these children’s lives, perhaps their stories will encourage a more rehabilitative approach to juvenile detention.

—Steve Liss, October 2003