20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-001

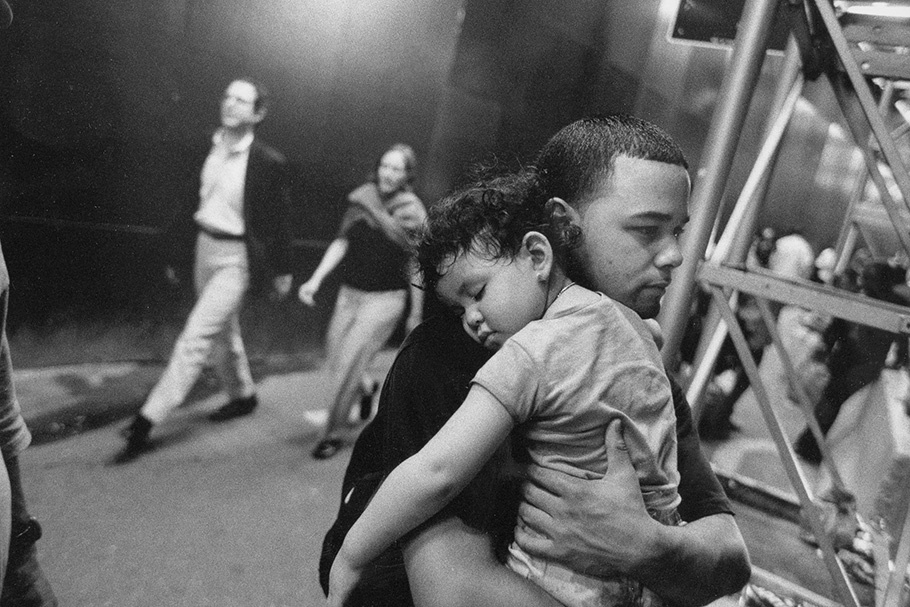

Outside the Texas State Prison. A recently release inmate greets a relative.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-002

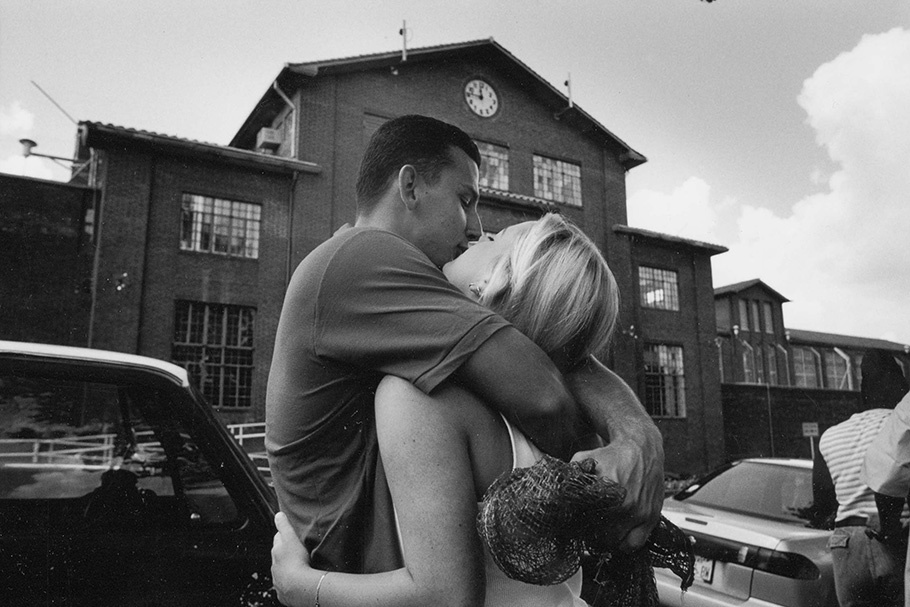

Outside the Texas State Prison. A recently released inmate kisses his girlfriend.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-003

Outside the Texas State Prison: Every afternoon, hundreds of state prisoners are released in downtown Huntsville. After signing parole papers, the ex-convicts exit through the front gate. A few are greeted by waiting relatives, but most walk three blocks to the Greyhound bus station. They have all received a $50 check and a one-way bus ticket home.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-004

From the series The True Cost of Prison.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-005

From the series The True Cost of Prison.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-006

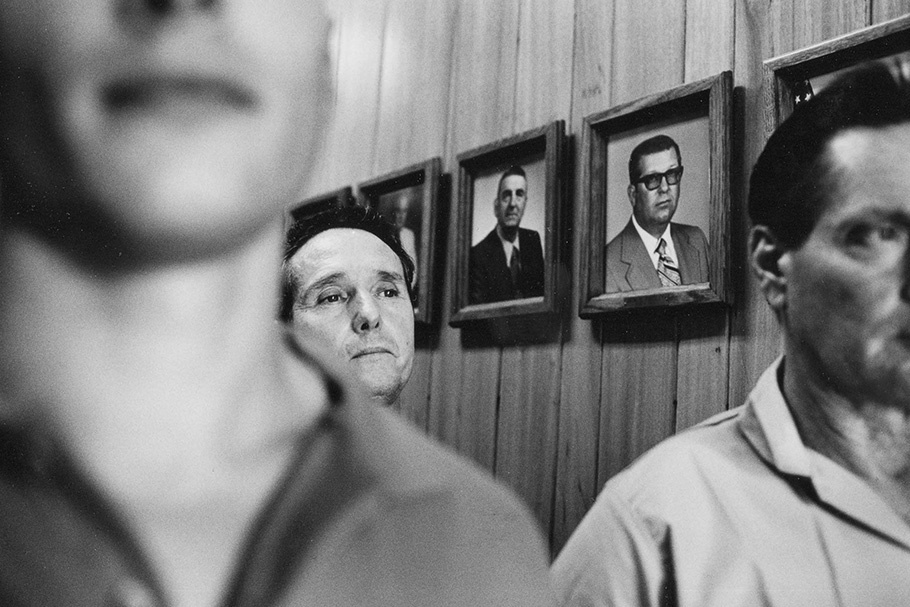

Twelve wrongly convicted men arrive at the Swisher County courthouse for a special judiciary hearing that will set them free. Although they have spent the last four years in prison because of the perjured testimony of a single narcotics officer, they are still the property of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, and so arrive in chains.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-007

From the series The True Cost of Prison.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-008

From the series The True Cost of Prison.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-009

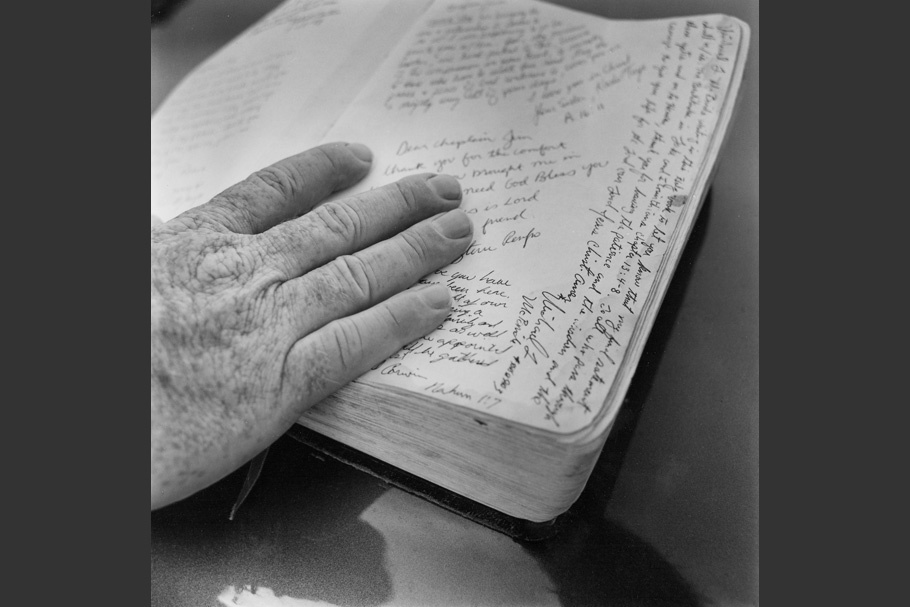

At the Texas State Prison: Jim Brazzil, chaplain, 114 executions. Since Karla-Faye Tucker first asked to say goodbye before her execution in 1998, Brazzil's bible has been signed by every inmate put to death.

Ever since the United States Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976, Texas has led the nation in executions. With over forty lethal injections scheduled a year, the small town of Huntsville has an execution take place more than once every two weeks.

On the surface, all is well in Huntsville. The majority of people in Texas continue to support the death penalty. But for the men and women who must carry out the sentence of the court, the emotional strain of witnessing so many executions is tremendous.

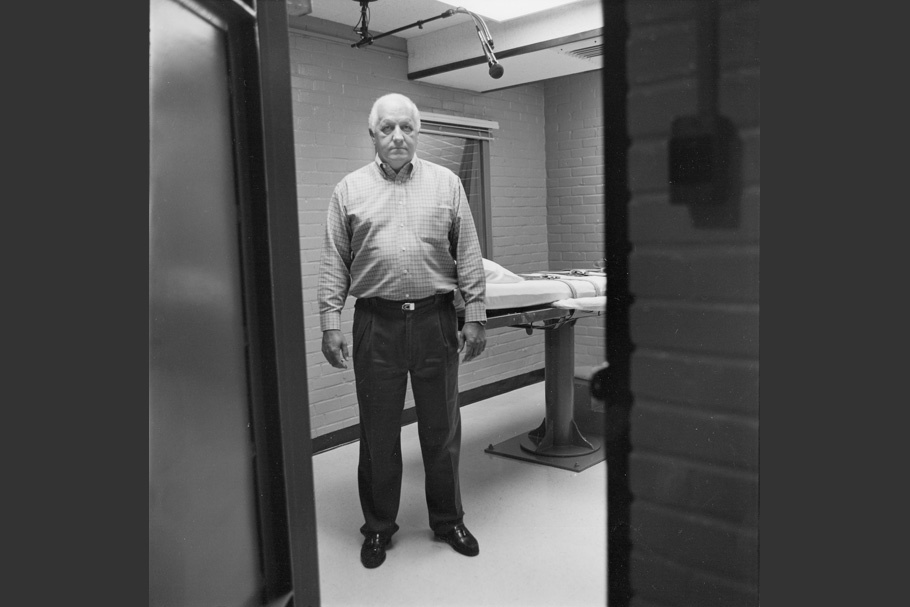

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-010

Jim Willett, warden, 75 executions.

"There are times when I'm standing there, watching those fluids start to flow, and I wonder whether what we're doing here is right. It's something I'll be thinking about for the rest of my life."

Ever since the United States Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976, Texas has led the nation in executions. With over forty lethal injections scheduled a year, the small town of Huntsville has an execution take place more than once every two weeks.

On the surface, all is well in Huntsville. The majority of people in Texas continue to support the death penalty. But for the men and women who must carry out the sentence of the court, the emotional strain of witnessing so many executions is tremendous.

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-011

At the Texas State Prison: Leighanne Gideon, reporter, 52 executions.

"You'll never hear another sound like a mother wailing when she is watching her son being executed. There's no sound like it."

Ever since the United States Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976, Texas has led the nation in executions. With over forty lethal injections scheduled a year, the small town of Huntsville has an execution take place more than once every two weeks.

On the surface, all is well in Huntsville. The majority of people in Texas continue to support the death penalty. But for the men and women who must carry out the sentence of the court, the emotional strain of witnessing so many executions is tremendous.

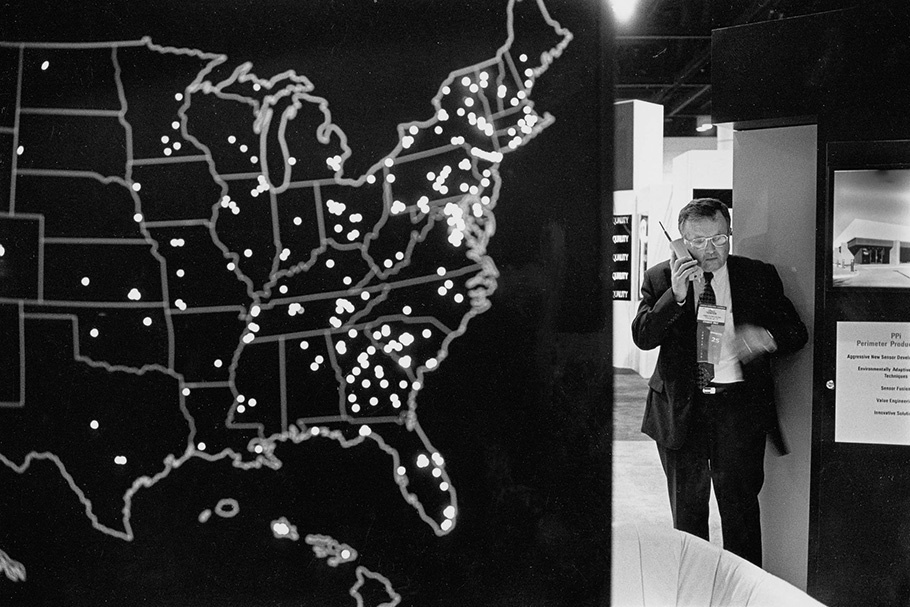

20031016-lichtenstein-mw08-collection-012

A vendor at the annual American Correctional Association convention works the phones, selling security products to the nation's prison system.

Andrew Lichtenstein, a native of New York City who currently resides in Brooklyn, is a documentary photographer who works on long-term stories of social concern.

Lichtenstein’s work on prisons and incarceration has appeared in books, newspapers, and magazines, including U.S. News and World Report, Time, and The New York Times. His series of photographs titled “Witness to an Execution” inspired and accompanied a Sound Portraits radio documentary of the same name, which aired on NPR’s All Things Considered and won a Peabody Award in 2000. In the spring of 1999 his photographs appeared in Moving Walls, and in 2000, he received a Soros Justice Fellowship from the Open Society Foundations. Lichtenstein and journalist Eric Schlosser, another Soros Justice Fellow, are finishing a book about the prison system in America.

Andrew Lichtenstein

The photographs taken by Soros Justice Fellow Andrew Lichtenstein are part of an ongoing collaboration with investigative reporter and Soros Justice Fellow Eric Schlosser. Their work first appeared together in “The Prison Industrial Complex,” a 1998 Atlantic Monthly article, which is being expanded into a book. Schlosser describes the prison world that Lichtenstein explores in his photography.

It costs about $20,000 to keep someone behind bars for a year. Multiply that amount by two million (the number of men and women now incarcerated in the United States) and you get a rough estimate of the financial burden that prisons and jails now impose on American society. The money we spend on our correctional system, however, is a poor measure of its real cost. Over the past 30 years, the United States has embarked on an unprecedented cultural experiment, imprisoning more people for the sake of crime control than any other society in history. In a relatively brief period of time, the land of the free has become a nation of inmates, and the effects of this vast penal system are now inescapable.

The price paid by inmates is the most obvious. Separated from their families, subjected to rape and violence, exposed to a variety of communicable diseases, forced to survive in a realm where the powerful rule the weak without mercy, inmates in the United States gain a first-rate education in deviant behavior—at the government’s expense—that has little value outside the prison walls. It should come as no surprise that about half of the people released from prison are back in prison within three years. During that same period, two-thirds are arrested for some sort of crime. A system that succeeds all too well at delivering punishment fails miserably at preventing future criminal behavior.

The families of inmates also pay dearly for their crimes. The population of America's prisons is largely poor and urban. But the prisons are usually located in remote rural areas. Great hardships are endured in the effort to keep families together. It is an effort that rarely succeeds, creating a seemingly endless cycle of dysfunction. Children who grow up with a parent behind bars are far more likely than other kids to wind up in prison one day. Perhaps two million American children now have at least one parent behind bars. The failure of most inmates to rejoin society permanently, combined with the prospective failure of so many of their children, raises the specter of a growing, thriving criminal underclass in America. A prison sentence for one person may punish a family for generations.

The rural counties that have lobbied hard for new prison construction, as a form of economic development, seem to have benefited. The new prisons have brought new jobs, preserving many small towns that might otherwise have continued to decline. Beneath the surface, however, the prison industry comes at high price. Correctional officers spend their days behind bars, too, enduring dangerous and highly stressful working conditions. Their families must worry not only about their safety but also deal with the emotional problems they bring home. Those who witness or administer the ultimate punishment—the death penalty—live with troubling, first-hand knowledge that can scarcely be put into words. They confront the dehumanizing realities of a criminal justice policy that others celebrate from a safe distance. The prison boom of the past few decades has transformed the character of many rural communities, places that the founding fathers once praised as the bedrock of American freedom and democracy.

Andrew Lichtenstein’s photographs focus on the true cost of our prison system. They reveal more about the human toll than any dry academic text or set of government statistics.

—Eric Schlosser, October 2003