20130401-teh-mw20-collection-001

Quarry and temple. Bayin, Gansu, China, 2011.

A private temple set above a quarry. Quarries producing limestone, used for construction and as flux for the process of steel making, are among a number of common features found in industrial towns. Mining industries set up near mountains that provide coal and other valuable mineral deposits. Coal-fired power stations are located in the same area and steel plants that need energy also locate near the power stations. Coking plants are located nearby to convert coal into coke, which is also necessary for steel production.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-002

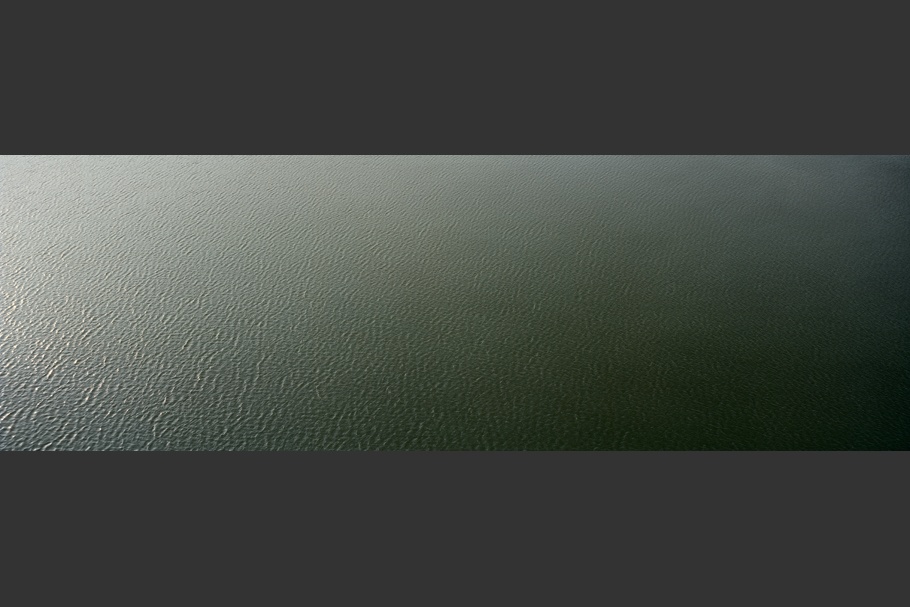

Yellow River. Sanmenxia, Henan, China, 2011.

The Yellow River viewed from the top of the controversial Sanmenxia Dam. Heralded as a great engineering feat, the dam was built in 1960 to tame the river. Its image was subsequently printed on the country’s bank notes. Yet within four years of opening, the dam had lost 40 percent of its water storage capacity because of silt, and its turbines were clogged. Despite renovations, the dam currently has less than 10 percent of its original storage capacity and generates only about 25 megawatts, compared to the expected 1,160. The dam has failed to prevent severe flooding upstream and still prompts much controversy, including government arrests of the project’s most outspoken critics.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-003

Banks of the Yellow River. Hejin, Shanxi, China, 2011.

A couple sits by the banks of the only remaining undeveloped section of the Yellow River on the outskirts of the small city of Hejin. Although China has roughly the same amount of water as the United States, its population is nearly five times greater, making water a precious and increasingly sought-after resource. The heavily industrialized area around Hejin contains some of the most polluted waters in the river. In 2007, after surveying the river, the Yellow River Conservancy Commission stated that one third of the river system had pollution levels that made the water unfit for drinking, aquaculture, industrial use, or even agriculture.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-004

Residential estate under construction. Linfen, Shanxi, China, 2011.

A new residential estate built on the edges of farmland, close to nearby factories. In the 1970s, Linfen was famous for its spring water, greenery, and rich agriculture, and was nicknamed “The Modern Fruit and Flower Town.” More recently, Linfen’s rich coal seams have transformed it into a center for the mining industry. The development has had a devastating impact on the city’s environment, air quality, farming, and health. According to a 2006 study by the Blacksmith Institute, Linfen was one of the top 10 most-polluted cities in the world.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-005

Industrial site. Lanzhou, Gansu, China, 2011.

A polluted pond hidden from public view in an industrial district near the newly landscaped banks of the Yellow River. Factories disposing waste illegally often pipe effluent deep underground or late at night to avoid being caught. Illegal dumping of chemical waste has become a widespread problem. About one third of the industrial wastewater and more than 90 percent of household sewage in China is released untreated into rivers and lakes.

As China continues to prosper, the public—fueled by a sense of individual rights related to increasing openness and prosperity—have shown an increased concern for the environment, which has led to more public disputes. In 2006, the government received 600,000 environment-related complaints, a figure that has risen roughly 30 percent each year since 2002.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-006

Desert. Bayin, Gansu, China, 2011.

A man from an illegal mine walks on a dirt track leading out of the mountains. Desertification is a serious problem, consuming an area greater than that taken by farmland. Nearly all of China’s desertification occurs in the west of the country and approximately 30 percent of the country’s surface area is desert. China’s rapid industrialization, overgrazing, and the expansion of agricultural land accelerate the advance of deserts that are now swallowing up a million acres of grassland each year.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-007

Highway construction. Lanzhou, Gansu, China, 2011.

The goal of the “Go West” policy, launched just before China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, was to develop the economies of China’s western regions. While massive investment has boosted output and effectively raised GDP in the western regions, the project failed to achieve its goal of eliminating the economic gap between eastern and western China. Over $325 billion has been invested in major infrastructure projects in the west, making it one of the biggest economic regeneration programs of all time.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-008

Cityscape. Lanzhou, Gansu, China, 2011.

The expansive cityscape of Lanzhou cloaked in a polluted haze. Since 1949, the city, once a former Silk Road trading post, has morphed from the capital of a poverty-stricken province into the heart of a major industrial area. It is the center of the country’s petrochemical industry and is a key regional transport hub between eastern and western China. Among the country’s 660 cities, more than 400 lack sufficient water, while over 100 suffer from severe shortages. Lanzhou is the largest and first city on the Yellow River but is often better known for its massive discharge of industrial and human waste. According to recent reports by the Chinese government and international NGOs like the Blacksmith Institute, Lanzhou is China’s most polluted city and one of the 30 most polluted cities in the world.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-009

Desert II. Bayin, Gansu, China, 2011.

An illegal, makeshift plant operates in the desert. Power lines lead to new industrial factories over the horizon. The new factories beyond the mountains are set far away from cities and have given birth to new small towns that have sprung up to support the new expansion in heavy industry such as cement factories and steel plants. Many of the heaviest polluting factories near the Bayin have been shut down in recent years as the state attempts to deal with environmental pollution in highly populated areas.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-010

Landfill construction. Hejin, Shanxi, China, 2011.

Workers unroll sheets of plastic to line the inside of a new landfill. This cavity was once farmland and continues to be surrounded by agricultural land.

Just over a generation ago, refuse was rarely a problem because families, then largely poor and rural, used and reused everything. A supermarket was uncommon and as a result so was plastic packaging. As cities have grown, urban support systems that provide public services such as landfills and waste treatment plants have been unable to keep up with the growing demand for the processing and disposing of waste.

China has recently surpassed the United States as the world’s largest producer of municipal solid waste. Most landfills are poorly managed and have only thin linings of plastic or fiberglass. These sites leach heavy metals, ammonia, and bacteria into the groundwater and soil, and the decomposing waste sends out methane and carbon dioxide. A farming society for thousands of years, most of China will be urban by 2017. No country has ever experienced such a large and rapid increase in its generation of waste; the implications both domestically and internationally are enormous.

20130401-teh-mw20-collection-011

New highway. Xian, Shaanxi, China 2011.

In 2011, China’s highway system became the longest in the world—longer than the United States, which had been the undisputed leader for at least 50 years.

In 1990, China produced 42,000 passenger cars. By 2004, the number hit one million, with 16 million cars on the nation’s roads. By 2000, motor vehicles were the leading cause of China’s urban air pollution and in 2010 it overtook the United States as the world’s largest market with the sale of 13.8 million new cars.

British photographer Ian Teh was born in Malaysia and came to London in his early teens. Upon graduating from the University of Bath with a degree in graphic design and winning the 1993 Time Out Photographer of the Year Award, Teh decided to travel to China to explore the country, photography, and his heritage.

Much of Teh’s photography is guided by and conveys his concern for social and environmental issues. His series, The Vanishing: Altered Landscapes and Displaced Lives (1999–2003), records the devastating impact of the Three Gorges Dam on China’s Yangtze River. In later works, such as Dark Clouds (2006–2008), Tainted Landscapes (2007–2008), and the book Traces (2009), Teh explores the consequences of China’s booming economy.

Teh has received numerous honors. He was awarded a place in the Joop Swart Masterclass in 2001, and in 2009, his work received honorable mention at the Prix Pictet prize. He won the Emergency Fund grant from the Magnum Foundation in 2012. Teh’s photography has been published in C International Photo Magazine, Newsweek International, and Time. In 2010, Granta published a 10-year retrospective of his photographs from China. He had his debut solo show in 2003 at Jack Shainman Gallery. Teh has exhibited both nationally and internationally, most recently with a solo show, Dark Clouds, at the Kunsthal Rotterdam. His photography is part of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s permanent collection. Since 2012, he has been a visiting photography lecturer at the University of Bath. Teh is represented by Panos Pictures and Agence VU’.

Ian Teh

Few rivers have captured the soul of a nation more deeply than the Yellow River in China.

Historically a symbol of enduring glory, a force of nature both feared and revered, the river in the 1990s ceased to reach the sea at all. This environmental decline is a tragedy with consequences extending far beyond the 150 million people the river directly sustains. The river’s plight also underlines the dark side of China’s economic miracle, an environmental crisis leading to scarcity of the one resource no nation can live without: water.

During the years I spent photographing the coal industry in China, I became interested in how economic development was affecting the country’s landscape. I was less focused on the individual human stories and more interested in the marks left by man and how they affected communities undergoing radical transformation.

My photographs play with the tension between the Yellow River’s place in Chinese culture and history and China’s emergence as a major economic power. I have always been struck by how the nation’s focus on getting ahead has marginalized other concerns. By using the landscape, I attempt to show what happens when an area that was largely rural becomes increasingly urban and industrial.

By depicting these landscapes as predominantly beautiful, almost dream-like, I seek resonance with some of the romantic notions about this once great river. At the same time, the images are meant to show the very negative physical impact of economic development. My images aim to reveal this disconnect and provide insight into the costs imposed on the environment and communities beyond the river’s immediate surroundings.

Unshackled development has improved the lives of many Chinese, but has also fueled environmental collapse. These topographical changes hint at the underlying political and economic forces at play in today’s China. There are appropriate laws to protect the environment and its people, but they are systematically overlooked as the ambitions of the state are prioritized over the rule of law.

These connections and the larger issues of development’s impact are what make photographing this fabled river interesting to me. China’s complex environmental problems go beyond linking pollution to its perpetrators. They are more deeply rooted in the way the country governs itself. By highlighting the challenges and contradictions of the Yellow River, I hope this work reveals the intricate forces driving China’s development.

—Ian Teh, April 2013