20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-005

Manama, Bahrain, February 21, 2011.

Tens of thousands of pro-government demonstrators gather to pray and show support for the Bahraini monarchy at the Ahmed al-Fateh Mosque in the capital Manama. The event was designed to counter the anti-government protests at the Pearl Roundabout.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-006

Ma’ameer, Bahrain, February 21, 2011.

Men listen to an audio recording of a speech made by top Shiite cleric, Sheikh Isa Qassim, at a mosque in the village of Ma’ameer.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-007

Malkiya, Bahrain, February 22, 2011.

The funeral procession of anti-government protester Abdulredha Mohamed Hasan Buhmaid, age 28. Buhmaid was shot in the head few days earlier and died from his injury, becoming the seventh victim of the uprising in Bahrain. Buhmaid’s funeral was held in his village, Malkiya, where some nine thousand people attended the funeral procession while some 100,000 participated in a protest in Bahrain’s capital, Manama, dubbed the “March of Loyalty to Martyrs” in honor of the seven victims killed.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-002

Malkiya, Bahrain, March 18, 2011.

Painted portraits of men killed during the uprising are seen at the Shiite Muslim village of Malkiya.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-001

Sitra, Bahrain, March 18, 2011.

Five thousand Bahrainis gathered at the funeral of Ahmed Farhan, a 29-year-old anti-government demonstrator who was killed by state security forces in the Bahraini island of Sitra. Earlier that day, the King of Bahrain, Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa, declared martial law, outlawing rallies and protests. However, thousands of mourners attended the funeral to support the Farhan family as they bury their son.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-004

Sitra, Bahrain, March 18, 2011.

Several thousand Bahrainis gathered for the funeral of Ahmed Farhan, a 29-year-old anti-government demonstrator who was killed by state security forces in the Bahraini island of Sitra. Earlier that day, the King of Bahrain, Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa, declared martial law outlawing rallies and protests. However, thousands of mourners attended the funeral to support the Farhan family as they bury their son.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-003

Manama, Bahrain, March 19, 2011.

The Pearl Monument, which has been the centerpiece of demonstrations by Shiite protestors in Bahrain, was reduced to rubble by the state armed forces. Bahrain’s security forces destroyed the 300-foot (90-meter) monument in order to erase a symbol of an uprising. Within a few days of the monument’s destruction, the country’s pro-democratic protests turned from a symbol of hope to one of repression.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-014

Cairo, Egypt, February 1, 2011.

A demonstrator is lifted as a rally marches in Tahrir Square calling for the end of the Mubarak regime.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-009

Cairo, Egypt, February 4, 2011.

Evening prayer at Tahrir Square after tens of thousands of opposition supporters flooded the streets of central Cairo.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-010

Cairo, Egypt, February 4, 2011.

Two days after repelling pro-regime attackers in bloody street fights, tens of thousands of people pack central Cairo waving flags and singing the national anthem as part of their emboldened campaign to oust President Hosni Mubarak.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-015

Cairo, Egypt, June 2011.

A cafe is dedicated to the singer Umm Kalthoum, who remains a cultural icon and symbol of Egyptian nationalism more than three decades after her death.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-008

Cairo, Egypt, November 23, 2011.

The battle zone along Mohamed Mahmoud Street in Cairo. At least 45 protesters died in the five days of street battles that began on November 19, 2011, to put pressure on the military, which took power after a popular uprising overthrew Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in February 2011.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-013

Cairo, Egypt, November 28, 2011.

Soldiers on the day of parliamentary elections hold off voters waiting for a polling place to open.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-012

Cairo, Egypt, June 18, 2012.

Supporters of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi celebrate in Tahrir Square after the Brotherhood claimed victory in the presidential vote.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-017

Cairo, Egypt, June 2012.

Supporters of Mohamed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood candidate, camp overnight in Cairo’s Tahrir Square during a protest against Egypt’s military rulers.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-011

Cairo, Egypt, December 14, 2012.

Protestors opposed to Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi wave Egyptian flags as they stand on a wall surrounding the presidential palace.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-016

Cairo Egypt, December 15, 2012.

Women waiting to vote in a referendum on a new constitution in Cairo’s Shoubra neighborhood. The document that Egyptians voted on was a rushed revision of the old Mubarak charter, pushed through by an Islamist-dominated assembly in an all-night session, after Christian and secular representatives quit in protest.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-018

Cairo, Egypt, December 15, 2012.

A polling station in Cairo’s Shoubra neighborhood. The referendum appeared to be another turning point for Egypt’s nearly two-year-old revolution. After weeks of violence and threats of a boycott, Egyptians voted peacefully in a referendum on an Islamist-backed draft constitution. People hoped that this would end the three weeks of violence, division, and distrust between the Islamists and their opponents over the ground rules of Egypt’s promised democracy.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-019

Ras Lanuf, Libya, March 11, 2011.

Anti-Qaddafi rebels flee under fire from the Libyan army.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-025

Tobruk, Libya, March 24, 2012.

The February 17 Restaurant in Tobruk looks out onto Liberation Square, the scene of the town’s first revolutionary celebrations in February 2011 after rebels expelled Qaddafi’s forces from the eastern part of the country. Before the revolution, the restaurant was called “Fatih”—which in Arabic means “conqueror” or “victor” and was a common name for things under Qaddafi’s rule. On February 17, when the revolution started, the owners promptly renamed their restaurant to commemorate the beginning of the uprising. Once Qaddafi was defeated, the people of Tobruk renamed the square to Liberation Square.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-026

Shahat, Libya, March 25, 2012.

Rabheen (left) and Miley Esbak visit their brother Ali’s grave in the town of Shahat in the Green Mountains of eastern Libya. Ali, 17, was killed while fighting on the frontline against Qaddafi’s forces in April 2011. Now the family hopes that Libya’s people can secure their rights, and restore the dignity and greatness for Libya that they say Ali was fighting for.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-023

Benghazi, Libya, March 28, 2012.

Former rebels play sports and lift weights at a former rebel brigade that is now being transformed into a “rehabilitation center” for youth who participated in the war. “Our motto now is ‘From a revolution to a state, and from liberation to reconstruction,’” says the camp’s spokesman Adel Shoahdi. The camp’s new roster of activities—ranging from language classes to computer training, sports, and counseling—offers former rebels, especially those not interested in joining the military or police, a way to reintegrate into Libyan society after the year-long war that toppled the regime of Muammar Qaddafi.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-029

Ajdabiyah, Libya, March 29, 2012.

A man stands inside his apartment that was ruined by heavy shelling.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-027

Sirte, Libya, March 31, 2012.

The city of Sirte sustained severe damage during the Libyan war, but almost all of the destruction came as the result of heavy shelling in September and October 2011. Sirte is the hometown of the late Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi, and it was one of the last loyalist holdouts in the nearly year-long revolution, which ultimately resulted in Qaddafi’s capture and killing at the hands of the Libyan rebels.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-024

Sirte, Libya, March 31, 2012.

Children ride bicycles in “Zone Two,” the hardest hit neighborhood in Sirte, the late Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi’s hometown. Sirte was one of the last regime strongholds in the nearly year-long war that toppled Qaddafi’s 42-year-old regime. Many residents say they were Qaddafi supporters, and they worry about what will become of them and their tribe in the new Libya.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-022

Misrata, Libya, April 1, 2012.

Tripoli Street in Misrata.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-028

Misrata, Libya, April 1, 2012.

A young girl stands inside a newly opened museum in Misrata. The Ali Hassan al-Jaber Martyr exhibit is named for a Qatari Al-Jazeera cameraman who was killed covering Libya’s revolution. It also displays, in meticulous detail, the horrors and tragedies of Misrata’s own experience with the war. On weekends, hundreds of people from across the country visit the museum. Here they find exhibits featuring portraits of the war-ravaged city’s 1,215 “martyrs”; rows of tanks, rockets, missiles, and mines; official documents detailing the regime’s corruption, and the ID cards of its soldiers and mercenaries; pictures of the wounded, the fighters, and the journalists who covered them; the dictator’s clothes and furniture; and even the famed gold-painted fist statue that Misratan fighters uprooted from Qaddafi’s compound in Tripoli and brought home as their prize.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-021

Misrata, Libya, April 1, 2012.

Misrata’s largest prison houses some 860 prisoners of war, most of them captured from stronghold towns of the late Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi. Former rebel fighters-turned-militia members control this makeshift prison and its inhabitants, along with at least six other known prisons in the war-ravaged coastal city. The militias say prisoners are treated well; they provide ample food and medical care to the men held captive here. But some of the men say they have been in captivity for more than a year without seeing a lawyer or any sign of an impending trial; many insist that they are also innocent. With the Libyan justice system still in disarray, the fates of pro-Qaddafi supporters—those who fought for or sympathized with Qaddafi—hang in limbo.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-020

Tripoli, Libya, April 2, 2012.

Haroun Milad, 12, and his brother Moussa, 14, survey the wreckage of Qaddafi’s once-impenetrable residential compound, Bab al-Aziziya, in Tripoli. After living through months of war and bombardment in Tripoli, this is their first time visiting the remains of their former dictator. The boys’ father says they are optimistic about Libya’s future—that the country has what it takes to become a prosperous, democratic society.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-039

Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, December 1, 2011.

A portrait of Mohamed Bouazizi hangs outside the governor’s office almost a year after he set himself on fire. Bouazizi, a young street vendor, killed himself near the office in protest against the government.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-030

Sanaa, Yemen, May 2011.

A demonstration at Change Square outside of Sanaa University. The protesters come from all regions of Yemen. For four months, they prayed together, shared meals, and debated the future of their country.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-035

Sanaa, Yemen, May 2011.

Yemeni women at the tent city outside Sanaa University visit a shrine to demonstrators killed during protests.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-034

Sanaa, Yemen, October 1, 2011.

Young girls scramble onto a fence during a protest in Change Square.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-033

Sanaa, Yemen, July 13, 2012.

In the capital, residents and protestors dismantle a sprawling tent city that was home to thousands of protesters for more than a year. Some refuse to leave the tent city at Change Square. Others say it’s time to get on with building a country.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-032

Hajar, Yemen, July 2012.

A member of the Popular Committee, a group of locals who have banded together to fight the jihadists in Hajar, takes a mid-afternoon break to chew qat, a mildly narcotic leaf popular with Yemenis.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-036

Sanaa, Yemen, September 29, 2011.

Saddam Nazhwan, 25, from Al-Mahweet, was wounded by gunfire during the protests.

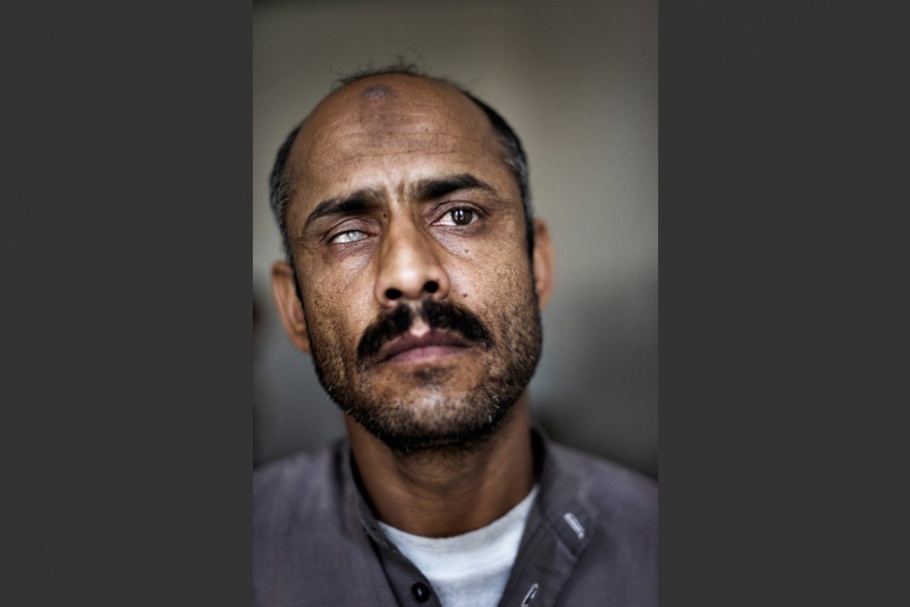

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-037

Sanaa, Yemen, September 29, 2011.

“I am ready to sacrifice to bring change,” says Saleh Ali Ahmed, 40, who was shot by security forces.

20130401-kozyrev-mw20-collection-038

Sanaa, Yemen, September 29, 2011.

“Victory or death. Even if my legs and hands are cut and even if my children are dead, we have to change,” says Ameer Ahmed, 33, who was recently wounded in clashes with security forces.

As a photojournalist for the past 25 years, Yuri Kozyrev has witnessed many world-changing events. Born in Russia in 1963, Kozyrev started his career documenting the collapse of the Soviet Union and then capturing the changes in his home region for the Los Angeles Times in the 1990s. Kozyrev started covering international news in 2001 and was in Afghanistan immediately after September 11. Between 2003 and 2009, he lived in Iraq and photographed the different sides of the conflict as a contract photographer for Time magazine. Since 2011, Kozyrev has documented the uprisings in the Middle East and their aftermaths in Bahrain, Tunisia, Yemen, and especially Egypt and Libya.

Kozyrev has received several World Press Photo Awards, the Overseas Press Club of America’s Olivier Rebbot Award, and the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award for Photojournalism. In 2008, he received the Frontline Club Award for his coverage of the war in Iraq. “My Year On Revolution Road,” his work for Time magazine documenting the revolts in Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen, won the 2011 Visa d’or News at the Visa pour l’Image International Festival of Photojournalism. Kozyrev’s other work has won the Photo Trophy and the Public Prize at the 2011 Bayeux-Calvados Award for War Correspondents, Photographer of the Year at the 2011 Pictures of the Year International competition, and first prize for spot news at the 2012 World Press Photo contest.

Between 2011 and 2012, On Revolution Road was shown in 10 different countries. Other exhibitions include the group exhibition Révolutions Arabes, and Russie(s), a showcase of work from Russia by Kozyrev and photographer Stanley Greene, at Maison de la photographie Robert Doisneau. Kozyrev is represented by NOOR.

Yuri Kozyrev

When a series of Arab uprisings first erupted in Tunisia in December 2010 and sparked protests in multiple Arab countries, I was assigned by Time magazine to photograph Cairo’s Tahrir Square where thousands of Egyptians were demanding political change.

As demonstrations swept the region, I documented uprisings in several countries but kept a particular focus on Egypt and Libya.

Much of the reportage on these events has focused on what they had in common. Yet as I crisscrossed the region, I became conscious of many differences. Rebels in Libya and protesters in Bahrain may have both been fighting tyranny, but their approach and aspirations were not the same.

I concluded that each revolution must be assessed in its own context. Each has a distinctive character and impact. Each therefore demands its own narrative.

In the end, the differences between the aftermaths of the region’s revolutions may be more important than their similarities.

Upon returning to Libya in 2012, I found the country in the midst of a great, collective exhale. Libyan journalists and politicians were navigating new and unfamiliar terrain. Families emerged from the rubble. The violence and shootings decreased. The most marvelous thing I found was optimism; despite the challenges they faced, many Libyans seemed hopeful.

In Yemen, after former president Ali Abdullah Saleh transferred power to Vice President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi in February 2012, Western media often focused on threats from Al-Qaeda and U.S. drone strikes on suspected militants. Most accounts overlooked the real challenges facing Yemenis. Many feel the revolution’s aftermath has not brought substantial change, but rather political instability, violence, and shortages of basic necessities such as water.

Tahrir Square, the hub of the popular uprising that toppled former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak last year, remains the center of protests and violent clashes between citizens and government forces. The last time I was in Tahrir Square there were thousands of bearded men celebrating the victory of the Muslim Brotherhood and its candidate, Mohamed Morsi, in Egypt’s first competitive presidential election. The past year has shown that the groups driving a revolution will not necessarily be the ones that gain power to build democracy.

—Yuri Kozyrev, April 2013