20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-001

Northern China, October 2003.

Kim Jeong-Ya (a pseudonym), 67, who lives near the North Korean border in Yanji, China, belongs to a handful of Chinese activists who have dedicated their lives to helping North Koreans make a safe passage from North Korea to South Korea via mainland China. Most foreign activists are simply expelled from China if caught participating in assistance missions, whereas, local Chinese and some South Koreans have faced severe punishment. Kim has been imprisoned twice and beaten up by North Korean agents operating in China. Kim’s relatives, who did the same kind of support work “disappeared” in North Korea. Since her release from jail, Kim has been under intense police surveillance. Her meager life savings was confiscated by local authorities, and she is not allowed to leave her home in the suburbs of Yanji.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-002

Northern China, January 2004.

Footprints in the snow lead to the border between China and North Korea.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-003

Seoul, Korea, November 2008.

Park Lee Hwan (a pseudonym), 67, stands in the hallway of a building that houses North Korean refugees living in Seoul. It took her five years to travel clandestinely from China to South Korea. Initially, Park was planning to visit her relatives in China and do temporary work, but her relatives convinced her not to return to North Korea. Park made her way to Beijing, where she presented herself at the South Korean Embassy. Embassy staff sent her to a third country, the Philippines, and then she went to Seoul. Park’s four daughters, who remain in North Korea, do not know that their mother has left China and now lives in Seoul. Park says South Korea is “paradise” compared to North Korea.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-004

Northern China, October 2007.

The Tumen River defines a section of the border between North Korea and China.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-005

Northern China, November 2007.

A 20-year-old refugee from North Korea in a farmhouse in northern China hides his identity. He left his mother and sister behind in North Korea. He used to be a road worker, but was constantly hungry. “The safest thing would be not to move at all because if you do physical activities, you get hungry,” he said. In China, he works as a farm laborer and a construction worker. If he’s lucky, he makes about 40 euros a month, but he says his boss often does not pay him and locals—who know about his illegal status and that he cannot seek help—beat him.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-006

Northern China, October 2008.

The official demarcation line between China and North Korea in Yanji that facilitates border trade, but is also used as one of the repatriation channels to return refugees caught in China.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-007

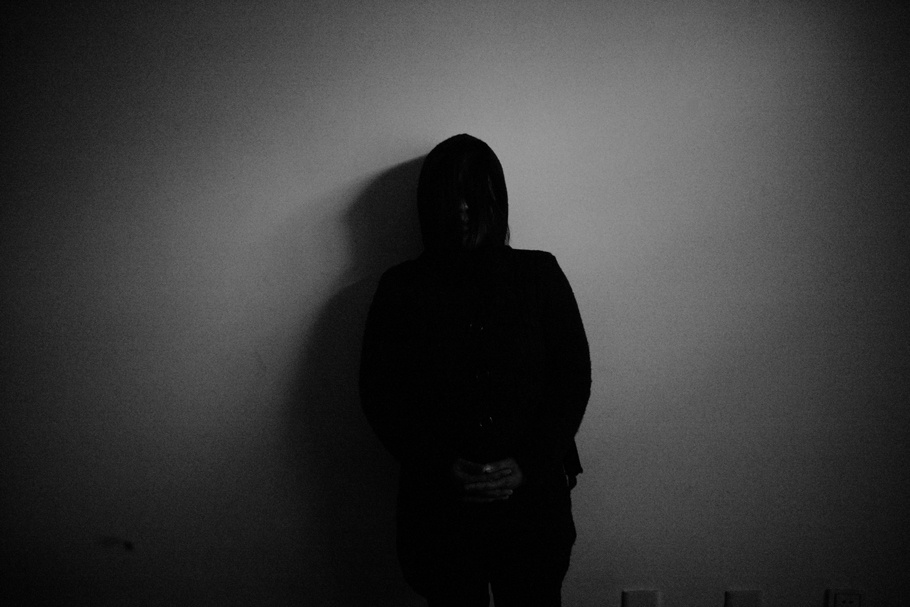

Northern China, November 2007.

Lee Jong-sin (a pseudonym) hides her identity. She waded through the icy water of the Tumen River up to her neck to reach the Chinese border. After walking half naked in the dark for a few kilometers, she found a small house where the residents gave her clothes. Lee’s three daughters and one son remain in North Korea. They know Lee lives in China, and she’s been told that the police in North Korea have put her house under surveillance to prevent other family members from fleeing the country.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-008

Northern China, October 2008.

The Tumen River marks the border between North Korea and China and is crossed by many refugees when it’s frozen in winter.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-009

Northern China, October 2007.

A young woman from Hoeryong County in North Korea hides her identity.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-010

Northern China, November 2008.

A truck passes the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge that connects the city of Dandong in China and the city of Sinuiju in North Korea. The bridge, just like other “official” transport lines between China and North Korea, is also used as a repatriation tunnel for North Korean refugees caught in China.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-011

Northern China, November 2007.

Chol (a pseudonym), a nine-year-old North Korean boy, shows a picture of the place where he was raised by his grandparents in North Korea. Chol was smuggled to China and hopes to follow his parents to South Korea.

20130401-hesse-mw20-collection-012

Northern China, October 2008.

The Tumen River marks the border between North Korea and China and is crossed by many refugees when it’s frozen in winter.

Katharina Hesse was born in Germany. After studying Sinology and Japanese at the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations in Paris, she moved to China as a graduate student in 1993.

Hesse is a self-taught photographer who has worked throughout Asia for nearly two decades. Her work primarily focuses on social issues in China such as youth and urban culture, religion, and North Korean refugees. Her work has appeared in publications including Courrier International, Courrier Japon, Der Spiegel, D della Repubblica, Die Zeit, EYEmazing, Financial Times (UK & Germany), FT Magazine, Glamour (Germany), Marie-Claire, Le Monde, Le Monde Diplomatique, Le Monde 2, OjodePez, 100Eyes.org, Reporters Without Borders (yearbook 2010, Germany), Stern, Time (Asia), Vanity Fair (Italy & Germany), and Zeit Magazin. In 2011, Hesse and writer Laura Day published Human Negotiations, a book exploring the daily lives of sex workers in Bangkok, Thailand. She is represented by laif Agentur für Photos & Reportagen.

Katharina Hesse

I began photographing North Korean refugees on the Chinese border about nine years ago, when an editor at a U.S. magazine contacted me for a photo assignment but was reluctant to give any details over the phone. Upon arriving in Northern China, I felt like I had entered a different world. As I accompanied a reporter in the barren border region, I listened to horrific tales of survival and violence: hungry people eating roots and grass or being shot for stealing food; civilians fleeing soldiers and living in a constant state of fear.

As we traveled along the border, I heard similar stories repeatedly: people dying of hunger; authorities violently punishing people for stealing food; teenage North Korean defectors missing their families; men in tears, overwhelmed with guilt about those they had left behind. At one interview, a young boy asked what the white liquid was when he saw his first glass of milk.

North Korea’s repressive regime uses selective food allocation as a tool to maintain loyalty among those deemed politically and economically useful. Meanwhile, state-run media produces propaganda designed to convince North Koreans that they are better off than people elsewhere.

After experiencing a world like this, it just didn’t feel “right” to take pictures and move on to the next job. The fear among these people was overwhelming. It was only on the condition that their identities were protected that I could photograph them. Locations could not be recognizable and names could not be used in text. To my surprise, North Koreans in Seoul made similar demands even though they had fled the North years ago.

Recent increases in access to foreign media and trade with businesspeople from neighboring countries like China have given many North Koreans more information about the outside world and the poor conditions in their own country.

Although North Koreans could be eligible for official UN refugee status, China prefers to categorize North Koreans as economic migrants. Therefore, most North Korean refugees on the border live in limbo without any protection from either China or international organizations like the UNHCR.

Borderland provides a more intimate and personal narrative to existing media coverage of North Korea as the world’s “most reclusive” communist country. As media attention fluctuates, North Korea’s refugees remain an enduring presence whose stories need to be told.

—Katharina Hesse, April 2013