20130401-weber-mw20-collection-001

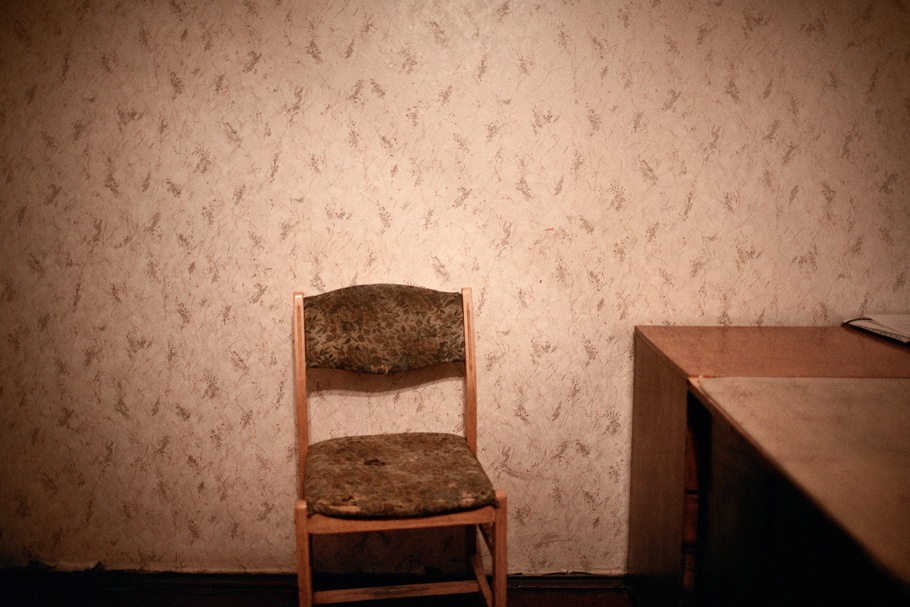

Interrogation room. Ukraine, March 2011.

A chair is the ultimate weapon in the interrogator’s arsenal. It can be used to manipulate and control the suspect, defining the balance of power within the room.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-002

Interrogation room. Ukraine, March 2011.

Fearing a reprisal from the detectives, a suspect contemplates sharing information with police, making him what all “good police” look for: an informant.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-003

Interrogation room. Ukraine, February 2011.

A woman arrested for public drunkenness and suspected of battery of her children is questioned. The police keep her under strict surveillance, which prompts her to check in with them on a monthly basis.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-004

Interrogation room. Ukraine, March 2010.

A teenage boy, just two weeks shy of his 16th birthday, is hauled in for questioning by a local police detective who was prompted by a sense of “paternal devotion” to try to change his increasing criminal behavior. To humiliate him into submission, the detective wrote “dibil” on his forehead, which means “cretin,” “imbecile,” “moron.” The detective described a downward spiral into larger and larger criminal activities and threatened to send the boy into adult prison if he didn’t straighten out. He has not committed a crime since.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-005

Interrogation room. Ukraine, February 2011.

An uncooperative sex worker is threatened by the authorities that they will take away her children unless she confesses to her crime.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-006

Interrogation room. Ukraine, March 2011.

A man frequently arrested for metal thieving, drunkenness, and beating his wife is brought into the police station again for questioning. When the police are behind on filling their quota, they like to bring in the usual suspects.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-008

Interrogation room. Ukraine, February 2011.

A man accused of dealing drugs pauses before signing his confession and accepting his fate.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-009

Interrogation room. Ukraine, February 2011.

Often, the police are more interested in turning suspects into informants than sending them to jail. Jail time is often a threat, which usually works. Ukrainian prisons are notorious for their abusive conditions.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-010

Interrogation room. Ukraine, April, 2010.

A sex worker who went missing while she was on parole was finally found by police after weeks of searching. They were not amused with her behavior.

20130401-weber-mw20-collection-011

Interrogation room. Ukraine, February 2011.

Arrested on suspicion of stealing a truck full of new, factory-made windows, a suspect stays quiet, upsetting the detectives in the room and getting the upper hand in the interrogation. This bothers the police, and they change tactics.

Donald Weber was born in Toronto, Canada. Prior to pursuing photography, Weber trained as an architect and worked with Rem Koolhaas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture. Weber is the recipient of many fellowships and awards, most notably a 2007 Guggenheim Fellowship. He also received the Dorothea Lange-Paul Taylor Prize in 2006 for The Human Is an Atom That Won’t Be Split: Resisting History in Ukraine, by Larry Frolick and Donald Weber, which explores how Ukraine’s underclass reveals the secret life of Western globalization. In 2009, Weber was the recipient of the Duke and Duchess of York Prize in Photography. He won first prize, portrait stories, at the World Press Photo contest in 2012.

Weber is the author of two books. Bastard Eden, Our Chernobyl, depicts daily life in a post-atomic world. His latest book, Interrogations, examines authority and power in Russia and Ukraine. His work has appeared in numerous international publications including, the Guardian, Newsweek, the New York Times Magazine, Stern, and Time. Weber’s photography projects have been exhibited in galleries worldwide including at the United Nations, the Portland Museum of Art, the Alice Austen House in New York, and as part of a group show on Afghanistan at the Musée de l’Armée at Les Invalides in Paris. He is a member of the VII Photo Agency.

Donald Weber

Interrogations is about a place where justice and mercy and hope and despair are manufactured, bought, bartered, and sold; a sound-proofed factory where truth is both the final product and the one thing that never leaves the room.

From 2005 to 2012, I traveled through Russia and Ukraine photographing the physical and emotional ruins of the unstoppable storm we call history. Meeting and living with ordinary people who had survived much—from wars and conflict, to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, to the fall of the Soviet Union—I began to see the modern state as a primitive, bloody, and sacrificial rite of unnamed and unchecked power.

This project is the result of a personal quest to uncover the hidden meaning of the bloody 20th century, as displayed through private encounters with state power. With each image, I was looking to make a very simple photograph of an actual police interrogation, but also a complex portrait of the relationship between truth and power. For truth in this context is a complicit act, a mutual recognition—however fleeting—between those who hold, and those who must surrender to power. This work interrogates the interrogators.

Over 90 percent of all charges in the Russian judicial system end in guilty pleas, and only experienced criminals or highly-educated defendants stand a chance in such a justice system. It is not designed to give everyone a fair trial. Behind closed doors and outside the view of the public, the feudal system’s trial by ordeal is still very much with us. Without confessions and guilty pleas, courts everywhere would grind to a halt in an instant.

In this way, Interrogations is more than a documentation of the policing practices of a particular time and place. It is a meditation on what these interrogation rooms, and the people who enter and leave them, represent. They are young and old, male and female, weak unfortunates and hardened criminals, all orphans of secret histories and hidden dramas that are scripted and played out by the modern state.

—Donald Weber, April 2013