20100602-holst-mw17-collection-001

A Buddha statue, its face torn off by Cyclone Nargis in 2008, sits amid the ruins of a small shrine in Dalah on the very top of the delta close to Rangoon. Cyclone Nargis ripped through the Irrawaddy Delta in Burma, destroying villages, killing an estimated 140,000 people, and leaving another 2 million homeless and traumatized. When the cyclone’s high winds churned up enormous waves, people fled the flat delta to the sturdiest buildings they could find, usually schools and monasteries. Rangoon, May 2008.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-002

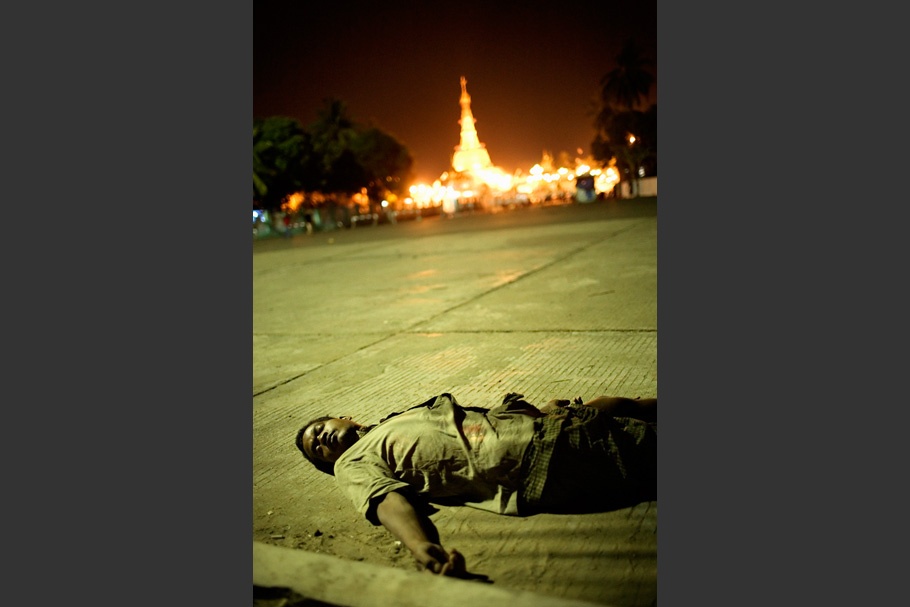

A day laborer passed out in front of Botataung Pagoda, considered one of the three holiest sights in Rangoon and said to contain hair relics of the Buddha. Day laborers are hired as porters at the jetties in front of the pagoda. They earn around one to two dollars a day, a meager salary rendered almost meaningless by the country’s 20-30 percent annual inflation. Rangoon, March 2007.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-003

Buddhism, Christianity, and spiritualism help sustain many ordinary Burmese. Some people think religion has given the Burmese people the strength to endure their terrible leaders. Others have suggested that Buddhism has fostered tolerance to such a degree that Burmese are less likely to rise up. The generals, who see themselves as devout Buddhists, have made serious efforts to co-opt and control Buddhism to their advantage. The Sangha Council, the official leadership of Burma’s Buddhist monasteries, is packed with junta supporters to such an extent that the Burmese speak of two kinds of monks—the generals’ "corrupt" monks and the people’s "pure" monks. Rangoon, October 2007.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-004

Soldiers pass through Sule Pagoda to close it down before protesting monks reach it in September 2007. Sule Pagoda is the second most important temple in Rangoon, and of major symbolic importance due to its location next to city hall, where most of the killings in the 1988 uprising took place. The day after this photo was taken, military and riot police prevented monks from entering Sule Pagoda and fatally shot Japanese photojournalist Kenji Nagai. Police and soldiers also sealed off Shwedagon Pagoda, the most holy pagoda in the country, and the starting point of most of the demonstrations. Rangoon, September 2007.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-005

A novice monk puts on a clean robe in a monastery in Rangoon. Novices like this young man will study for 10-13 years before they are able to pass required tests and be ordained as monks. It is not known how many monks were killed during the September 2007 protests, but the monks’ political activism has come with a high price: over 250 monks have been imprisoned and have received sentences ranging from 12 to 65 years for their alleged involvement in the protests. Many other monks have gone underground or have fled the country, unlikely to return until there is a change in government. Rangoon, October 2007.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-006

Despite its isolation, Burma is changing, and young urban Burmese are increasingly switched on to Asian and global youth culture through satellite TV and the Internet. The large numbers of youth involved in the September 2007 demonstrations indicate that the desire for reform that drove the 1988 student protests has not disappeared among Burma’s young people. Rangoon, April 2007.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-007

All communication is potentially monitored in Burma. Citizens need to obtain a special permit from the Ministry of Communication to own a cell phone or a satellite dish. The cost of a SIM card (up to US$2000 on the black market) helps ensure that most Burmese use traditional phone booths on the street or run by local shops. Burma is often thought of as an isolated country where no one can access information from the outside world. This is not so. Rangoon has Internet cafes on almost every block and satellite dishes mushroom from the city’s rooftops. While the regime understands that it can be undermined by technology, it also uses it to generate revenue and to monitor the population. Rangoon, July 2006.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-008

A father sits outside the mosquito net covered bed of his son, a patient at a shelter for people with HIV and TB. The son is one of the few patients who has family helping with their care. Stigma, due to lack of awareness about HIV and TB, and poverty that deprives families of the resources and time to care for the ill, take a heavy toll on many Burmese living with HIV and TB. Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, operates the shelter as part of its response to Burma’s HIV epidemic which is one of Asia’s worst, with an estimated 240,000 infected people. The regime continues to resist large scale foreign help even though only 13,000 of the 76,000 patients needing urgent care are getting treatment, largely from nongovernment sources. Rangoon, February 2009.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-009

An old man, seemingly sick and in poor health, lies outside a train station in Rangoon. The junta allegedly spends up to half of the country’s budget on its army while the expenditure on health care is below half a percent—equaling less than $1 per citizen per year. According to WHO, Burma has the second-poorest health care system in the world. Half of all Asia's malaria deaths occur here; the country has some of the world’s deadliest strains of TB and is facing a potentially devastating HIV epidemic. Rangoon, March 2007.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-010

Burmese men watch TV in a Rangoon teahouse late at night. TV is perhaps the freest medium in Burma. Widespread use of satellite dishes, either in private homes or in public places such as teahouses, gives many Burmese the option of watching news from CNN, BBC, and the Democratic Voice of Burma, as well as Premier League soccer matches and other sports. However, a few months after the 2007 protests, the annual satellite license fee was increased 166-fold. More recently, the junta-controlled newspaper, the New Light of Myanmar, has called for a ban on satellite TV, blaming it for decadent programs that undermine people’s sense of national pride. Rangoon, March 2007.

20100602-holst-mw17-collection-011

Teahouses are where people meet to talk about politics. As a result, the government considers teahouses, like universities, as breeding grounds for opposition. It is a common belief that teahouses are monitored by the military intelligence service. Burma’s 1988 uprising was sparked by an incident in a Rangoon tea house. A group of students playing a tape recorder were attacked by some drunken youths who seriously injured one of the students. Police initially arrested the assailant but then released him once they found out his father was a high-ranking government official. The next day, a few hundred students protested at the local police station where riot police fired upon them and killed one student. Rangoon, April 2007.

Danish photographer Christian Holst came upon photography in 1997, when a photographer friend of his uncle’s suggested that Holst come work for him. Photography soon became one of Holst's favorite pursuits along with working as a bike messenger and teaching children how to sail. He began his formal training first by working as an assistant at a photographers collective in Denmark, and then taking courses at Fatamorgana, the Danish School of Art Photography in 2000. He followed this the next year with classes at the Danish School of Journalism.

Holst was based in Bangkok until recently, when he relocated to Shanghai to work on stories in the region. He devotes most of his time to social issues and human rights stories. He is currently working on a long-term project about daily life under Burma’s military regime.

Holst has received numerous international awards, and his work has appeared in a range of American, European, and Scandinavian magazines and newspapers.

Christian Holst

Working in Burma as a photojournalist is difficult on many levels. I often feel like my images may be coming up short. I find it incredibly hard to visually convey the emotions and magnitude of the issues I know the Burmese are facing under Burma’s military regime, which has been in power for almost 50 years. It is a rule of harsh physical and psychological oppression. During the 1988 student uprising, more than 3,000 demonstrators were shot dead and thousands more arrested in the streets of Rangoon. In 2007, Burma’s generals brutally crushed peaceful demonstrations initiated by monks and students and jailed thousands of demonstrators.

Burma’s suffering was compounded in 2008 when Cyclone Nargis killed almost 140,000 people. Initially, the country’s paranoid generals responded with complete disregard for the population and made an already horrible situation worse by rejecting foreign aid for weeks.

The Burmese people suffer every day under a regime that is as inept as it is repressive. The military government’s economic policies have resulted in double digit inflation that devastates wages and salaries. Burma, once dubbed the “Rice Bowl of Asia,” can now barely feed itself and has gone from one of the region’s richest countries to one of the world’s poorest. The country is also on the verge of a potentially devastating health crisis due to the government’s inattention to HIV and AIDS, malaria, and TB. Burma’s health and education sectors are crippled by neglect and corruption. While the regime has built a number of universities, it does not allocate enough funds to operate them.

The generals seem to think that an oppressed, sick, and uneducated citizenry poses less threat to their power. Some maintain that the generals’ behavior is due to their commitment to keep Burma united. But the junta seems incapable of going beyond harsh military rule when attempting to govern Burma’s diverse, multiethnic society. Parliamentary elections are scheduled for 2010, yet they are likely to perpetuate military rule under a facade of legislative formality. The regime’s 2008 constitution allows the military to hold 25 percent of the seats in the new parliament and to control an appointed body with veto power over parliamentary decisions.

Despite these sad facts, the Burmese people show a quiet resilience to continue with their lives. Opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, whose party won the 1990 elections and who has been under house arrest for 14 of the last 21 years, has tried to help her fellow Burmese acquire courage and prevent fear from dictating their lives. She calls it “grace under pressure”—an ability to conduct oneself with decency and composure in the face of harsh, unremitting pressure.

On a basic human level, I am occasionally overwhelmed, sometimes frustrated, but mostly encouraged by what I see when photographing people in Burma. I feel utterly privileged to witness people who are so graceful under such harsh pressures.

—Christian Holst, June 2010