20100602-omi-mw17-collection-001

The photographer’s guide, Abul Kalam, points toward his home on the other side of the river Naaf, which divides Burma and Bangladesh. Kalam was born in Burma but has lived in a refugee camp in Bangladesh for years. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-002

A large number of refugees work in factories and fisheries and as day laborers in the town of Cox’s Bazar. Rohingya workers make half the earnings of the Bangladeshi workers they displace. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2010.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-003

A man digs deeps into a well for fresh water. Diminishing ground water levels are a big problem in and around the Nayapara refugee camp and the water supply is quite irregular. To make up for the lack of natural water sources in the camp, water is distributed through open taps once in the early morning and once in the late afternoon. In an attempt at a long-term solution, the government has agreed to allow excavation for a reservoir. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-004

After collecting wood from a nearby hill, a Rohingya refugee returns to the Nayapara camp. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-005

Rohingya children who are born in refugee camps are denied citizenship by both Bangladesh and Burma. Despite the harsh living conditions, many children are strongly attached to the camps which they consider home. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-006

A man carries rationed food to his hut. Every two weeks, refugees in the camp receive food rations from the United Nations World Food Programme. The amount of food depends on the number of family members. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-007

Fatima (pseudonym) wanted to save her daughter Anwara (pseudonym) from the girl’s stepfather, who tried to rape the 12-year-old girl several times. After Fatima prevented three attacks, her husband took revenge and stabbed Fatima seven times. A few days after this photograph was taken, Fatima died in a hospital in Dhaka. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-008

Anwara (pseudonym), now an orphan, with a photograph of her stepfather. Despite the presence of police in the camp, he tried to rape Anwara several times and eventually killed her mother, Fatima, who had protected her. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-009

Women wait for care at a medical center in a Rohingya refugee camp. Medical centers are a recent addition to the camps and though many do not meet basic medical standards, they are the only option refugees have for treatment. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-010

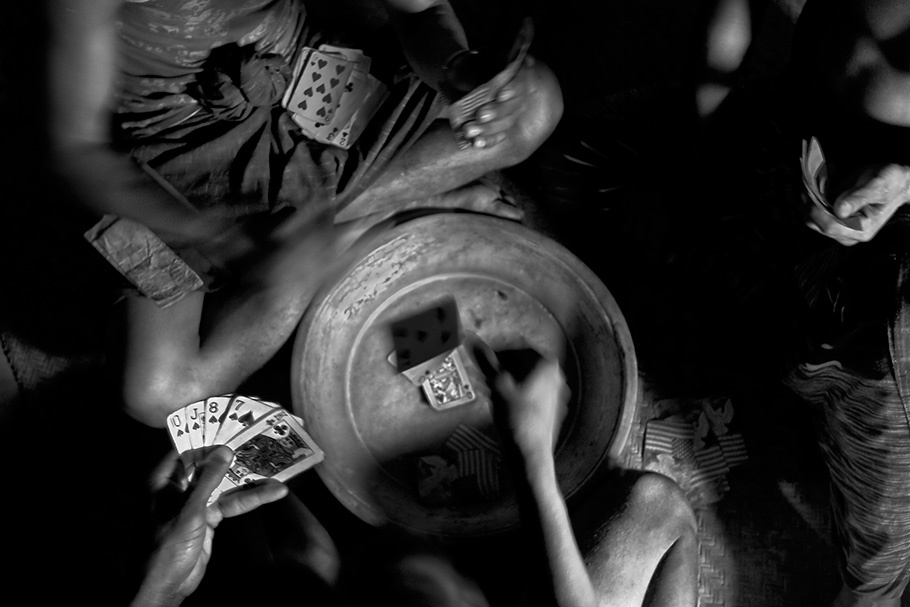

With few opportunities to receive education and unable to legally work, Rohingya youth play cards in the shade to pass the time and seek relief from summer temperatures that often surpass 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-011

Life in the refugee camps is particularly hard for Rohingya with physical or mental disabilities as they are completely dependent upon family members for their survival. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

20100602-omi-mw17-collection-012

Despite the harsh conditions in the camps, Rohingya try to maintain many of the rituals of daily life as a mother smiles upon her four-day-old son. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2009.

Saiful Huq Omi took up professional photography in 2005 after receiving a diploma from the Pathshala South Asian Institute of Photography. Omi currently works as a contract photographer for the New York Times and is represented by Polaris Images. His work has been published in Arab News, Asian Photography, Foto File USA, the Guardian, New Internationalist, the New York Times, Newsweek, and Time. Omi’s first book, Heroes Never Die: Tales of Political Violence in Bangladesh, 1989–2005, was published in 2006.

Omi has presented lectures on his photography at numerous institutions and has exhibited his work in galleries in Bangladesh, Germany, India, Nepal, the Netherlands, Pakistan, Russia, and the United States. He has received awards from the National Geographic All Roads Photography Program in 2006, the China International Press Photography Contest in 2009 (silver medal), and the DAYS JAPAN International Photojournalism Awards in 2010 (special jury prize). Omi was selected for the World Press Photo’s Joop Swart Masterclass in 2010 and was a finalist for the Aftermath Project in 2009 and for the Alexia Grant in 2009 and 2010. Omi’s ongoing work on Rohingya refugees is supported by the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund.

Saiful Huq Omi

For decades, the xenophobic, Burman-led military junta has refused to recognize the Rohingya, a distinct Muslim ethnic minority living in western Burma, as one of the country’s many ethnic nationalities. As a result, Rohingya have suffered human rights violations and a vast majority of them have been denied official recognition of citizenship.

Rohingya are subjected to countless forms of discrimination, including extortion and arbitrary taxation; land confiscation; forced eviction and destruction of their homes; and restrictions on marriage and movement. Rohingya continue to be used as forced laborers on roads and at military camps.

In 1978, a Burmese army campaign of killing, rape, destruction of mosques, and religious persecution drove 167,000 Rohingya across Burma’s porous border with Bangladesh. Under intense international pressure, the Burmese government eventually allowed many of the Rohingya who had fled to return. But from 1991 to 1992 a new wave of Burmese repression forced over 250,000 Rohingya to flee back into Bangladesh.

In Bangladesh, the UNHCR officially recognizes approximately 28,000 Rohingya as refugees. They live in squalid camps where medical care is practically nonexistent, where the majority of children and adults suffer from malnutrition, and where employment within or beyond the camp is forbidden. Access to formal education is rare and women are vulnerable to sexual violence and forced marriage. The great majority of Rohingya in Bangladesh are outside the camps where they barely survive and constantly endure ill-health, abuse, and exploitation, including from recruiters for Muslim fundamentalist groups. Rejected by the Bangladeshi government and fearing persecution in Burma, it is estimated that close to a quarter of a million Rohingya are living illegally in Bangladesh.

Despite these vast numbers, international media and most governments have ignored or forgotten the Rohingya for so long that they seem to no longer exist. Disowned by their home country and resented where they seek refuge, the Rohingya are not likely to experience change, until either the Burmese regime takes them back or Bangladesh improves the camps and gives official refugee status to all Rohingya in the country.

—Saiful Huq Omi, June 2010