20100602-waselchuk-mw17-collection-001

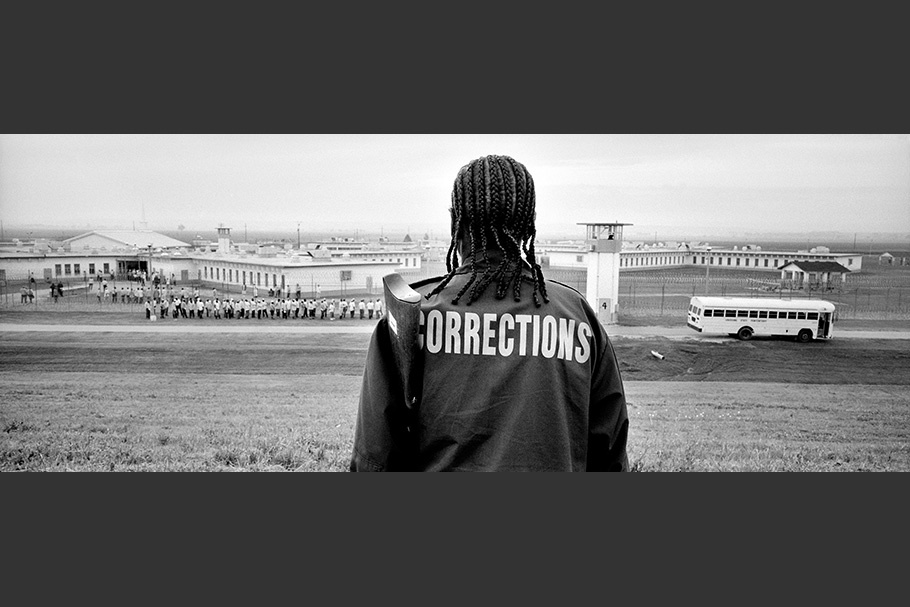

Mary Bloomer, a prison security guard at the Angola prison in Louisiana, watches from the levee as men form Field Line 15 at Camp C of the Louisiana State Penitentiary. Angola is a massive high-security prison, occupying delta land equal to the size of Manhattan. Those incarcerated there walk or ride in buses to and from the prison and their jobs every day. May 2007.

Lori Waselchuk is a documentary photographer and arts activist who seeks to inspire empathy and conversation through her photographs. Waselchuk’s work has appeared in magazines and newspapers world wide and has been used by several international aid organizations including CARE, Médecins Sans Frontières, the United Nations World Food Programme, and The Vaccine Fund.

Waselchuk is a recipient of the Aaron Siskind Foundation’s 2009 Individual Photographer’s Fellowship; a 2008 Distribution Grant from the Open Society Institute’s Documentary Photography Project; and the 2007 PhotoNOLA Review Prize. Her photo reportage on gender-based violence in Liberia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo was awarded the 2004 Southern African Gender and Media Award for photojournalism. Waselchuk was also a nominee for the 2009 Santa Fe Prize for Photography; a finalist in the 2008 Aperture West Book Prize; and a finalist in the 2006 and 2008 Critical Mass review.

In 2010, Waselchuk received support from the Baton Rouge Area Foundation to continue working on a project about bridges in New Orleans.

Waselchuk exhibits her work internationally in solo and group shows. Her photography has been featured in several books, including A Day in the Life of Africa (2002) and Women by Women: 50 Years of Women’s Photography in South Africa (2006).

Lori Waselchuk

"We believe that a person is a person through another person, that my humanity is caught up, bound up, inextricably, with yours." —Desmond Tutu

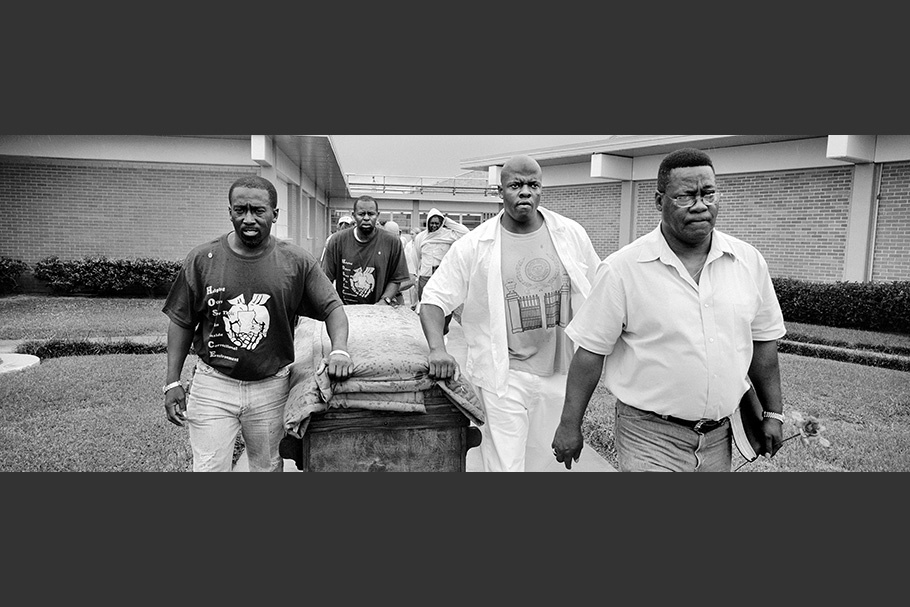

A life sentence at Angola, Louisiana’s state penitentiary, means life. Because Louisiana has some of the toughest sentencing laws in the United States, about 80 percent of the 5,100 prisoners at Angola are expected to die there. In the past, prisoners died alone and unattended in the prison hospital. But, a hospice program changed that. Incarcerated volunteers, now certified as hospice caregivers, have helped create an environment inside the prison where compassion is unconditional.

There are many reasons to tell the story of the Angola hospice program. As our sense of public safety decreases, the American prison population continues to expand. In 2008, 1 in every 99 adults in America was incarcerated. As the number of incarcerated people increases, so do the costs of housing them. States spent more than $49 billion on correctional services in 2007. Spurred on by demands to be tough on convicted criminals, courts continue to deliver longer sentences and parole boards continue to reduce parole and probation programs. A further consequence of Americans’ call to be “tough on crime” is that the incarcerated population is growing older.

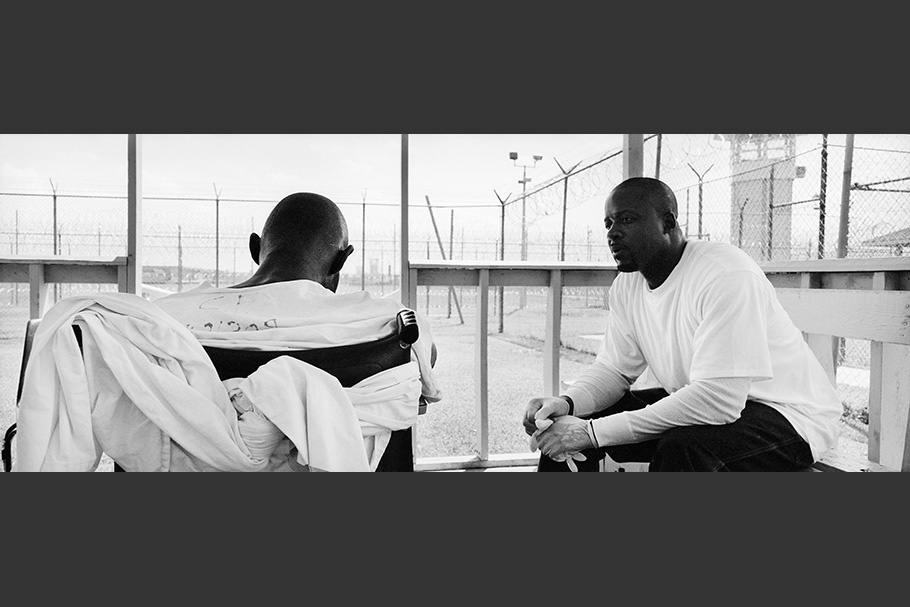

With my photographs, I intend on telling a story about the Angola hospice program that is likely to challenge stereotypes about incarcerated people, and, I hope, inspire solutions to change our criminal justice system. I want to tell a story about the hospice’s incarcerated volunteers because I see many lessons in their efforts to bring humanity and compassion to an environment designed to isolate and punish. Over the three years I’ve documented the program, I’ve witnessed how the Angola prison hospice team sparked a movement of empathy that not only spread throughout the prison population, but also influenced the prison’s security and medical staffs. Prison officials say that the program has helped to transform one of the most violent maximum-security prisons in the South into one of the least violent in the United States.

In doing this work, I have focused on moments of connection between caregiver and patient, which can reveal both love and vulnerability. I am inspired by the hospice volunteers’ courage to confront their own regrets and fears in order to accept their capacity to love. The people I have met have allowed me to visualize what I believe is at the core of addressing social problems: the recognition of our shared humanity.

—Lori Waselchuk, June 2010