20100602-oshagan-mw17-collection-001

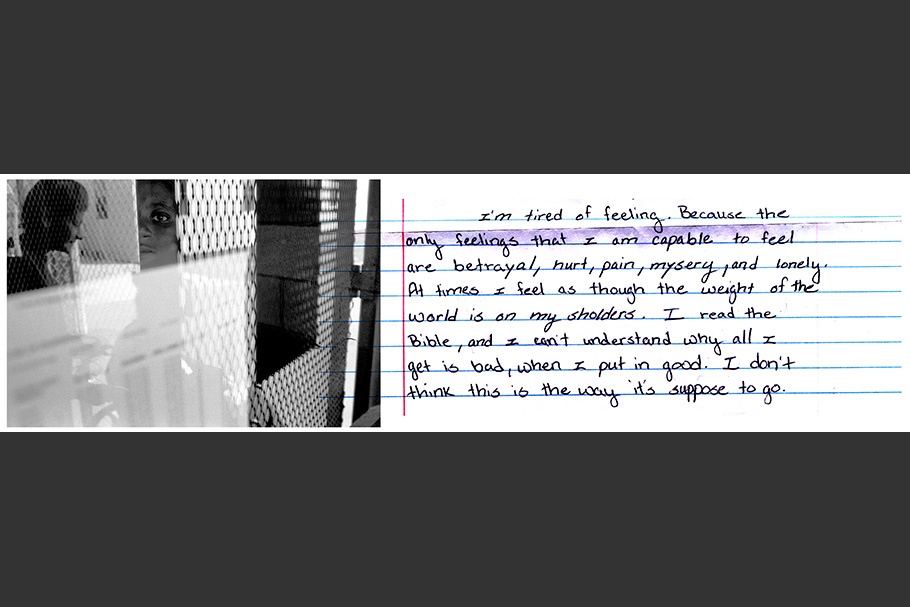

“My mom, she was schizophrenic. She disappeared out of everybody’s life [when I was] seven. No one has been able to track her down. [My dad was in the] state pen.”

—Sandra, 21 years old, Chowchilla State Prison, Chowchilla, California.

Sandra was a runaway. She had her first child when she was 12 years old, a result of rape. She spent most of her teenage years evading child protective services. At seventeen, she was arrested for accessory to murder after a phone card with her name was found at a murder scene. She was sentenced to twenty-seven years to life in adult prison. This was her first offense.

20100602-oshagan-mw17-collection-002

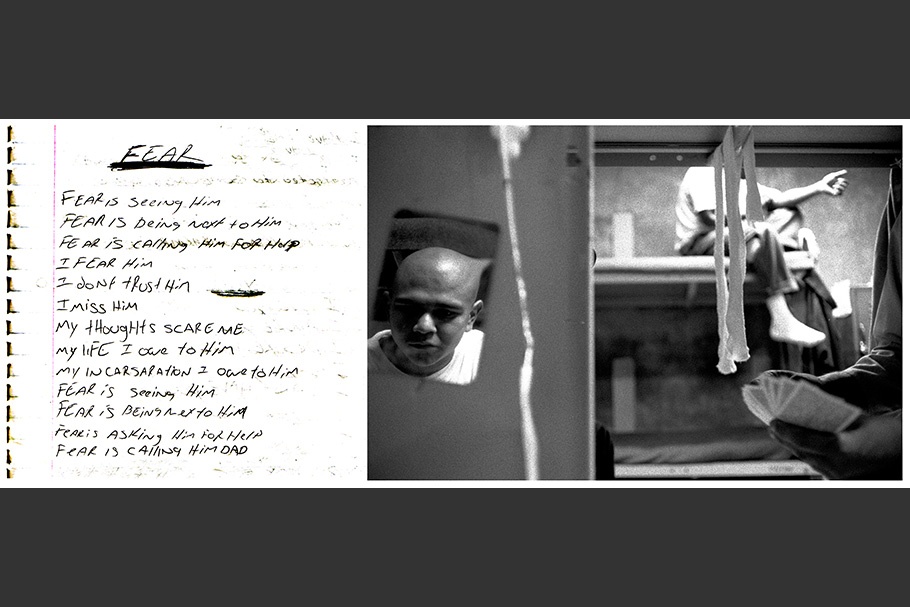

“I get to Avenal and the first person I see is my dad. We won’t be getting high together, you know, we won’t be doing certain things, won’t have any distractions. Maybe we can just sit down and have a conversation.The only lesson my father has taught me is the value of freedom. Now my freedom is gone and I owe that to my father too.”

—Efrain, 19 years old, Avenal State Prison, Avenal, California.

Arrested at 16 for aggravated assault and robbery, Efrain was sentenced to three years in juvenile hall then the adult prison at Avenal. Efrain has been released twice but then rearrested, first for a parole violation and then for driving without a license.

20100602-oshagan-mw17-collection-003

“I got in a fight in first grade and my dad had to come down and take me home. I would just have to wait for him. He’d get whatever he can to hit me. Like an extension cord. You can’t do nothing. And after it hurts too much, I can’t lay still anymore. I get up and I start to run. He’ll come after me.”

—Duc, 20 years, old, Tehachapi State Prison, Tehachapi, California.

Duc was 16 when he was arrested for attempted murder. Duc was with a couple of friends who were known gang members, and they were driving to a brawl with a rival gang. Duc was driving. They went down a back alley and saw their rivals’ car. A gun was fired out of the passenger’s side window of Duc’s car. Duc lost control of his car and crashed, pinning the other car against a telephone pole. He backed up and fled the scene. No one was hurt in the incident. Duc and his friends were apprehended, tried together, and all charged with first degree attempted murder, irrespective of their roles in the incident. When gun and gang enhancements were added to their sentences, Duc wound up with a prison sentence of 35 years to life for his first offense.

20100602-oshagan-mw17-collection-004

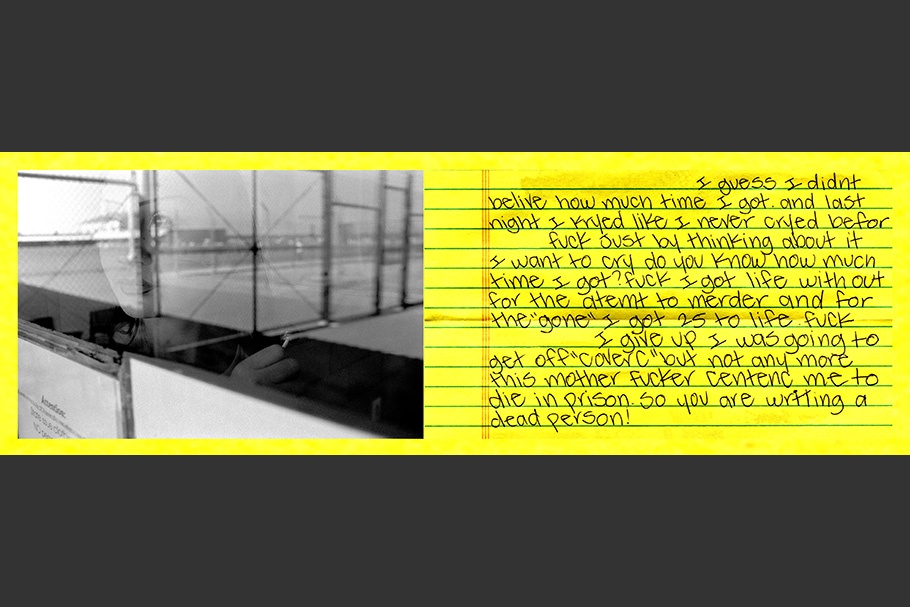

“When I was little I wanted to be just like my brother. He was in a gang. I admired everything he did. And I had my aunties, they gang banged. I used to ride around with them, watch them drink and do drugs. I’m in here for shooting my friend. She got paralyzed from the waist down and I got sentenced to life plus 25. My neighborhood told me to kill her. There was nothing else I could do.”

—Mayra, 19 years old, Valley State Prison, Chowchilla, California

Mayra was arrested at 16 for shooting her homegirl, Lizette, at point blank range and paralyzing her from the waist down. Lizette was sleeping with a member of another gang. Mayra was charged with first degree attempted murder and gave birth to her son, Jaime, in juvenile hall. She is now serving a life sentence at Valley State Prison.

20100602-oshagan-mw17-collection-005

“My stepfather, he was sexually and physically abusing me and my sister for, like, years. [It started when I was] like, nine.”

—Liz, 20 years old, Chowchilla State Prison, Chowchilla, California.

Liz was 15 when she was arrested for being an accessory to murder. Prior to her arrest, Liz was a runaway who had been living on the streets for five years. Liz was found guilty of standing by while a woman was strangled to death in an abandoned house in Santa Monica. This was Liz’s first offense and she was sentenced to 11 years in adult prison.

Born into a family of writers, Ara Oshagan studied literature and physics, but found his true passion in photography. A self-taught photographer, his work revolves around the intertwining themes of identity, community, and aftermath.

Aftermath is the main impetus for his first project, iwitness, which combines portraits of survivors of the Armenian genocide of 1915 with their oral histories. Issues of aftermath and identity also took Oshagan to the Nagorno-Karabakh region in the South Caucasus, where he documented and explored the post-war state of limbo experienced by Armenians in that mountainous and unrecognized region. This journey resulted in a project that won an award from the Santa Fe Project Competition in 2001, and will be published by powerHouse Books in 2010 as Father Land, a book featuring Oshagan’s photographs and an essay by his father.

Oshagan has also explored his identity as member of the Armenian diaspora community in Los Angeles. This project, Traces of Identity, was supported by the California Council for the Humanities and exhibited at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in 2004 and the Downey Museum of Art in 2005.

Oshagan’s work is in the permanent collections of the Southeast Museum of Photography, the Downey Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art in Armenia.

Ara Oshagan

A few years ago, Leslie Neale, a filmmaker-friend, invited me to photograph with her crew at the Central Juvenile Hall in Los Angeles. Her topic: young people being tried as adults for violent crimes ranging from first-degree murder to assault with a deadly weapon. They were all facing very harsh sentences, some even life in prison. In my mind, they were the worst of the worst. They were unimaginably far from my own life. I braced myself for the trip to the “inside.”

But that trip had little of the menace that I imagined. I did not meet any angry or tattoo-ridden kids decked out in the clothes and accessories that could mark them as members of the city’s gang culture. Rather, I found a group of ordinary young men and women who had signed up for a video production class being taught by Leslie. When I spoke to them, they were deferential. For them, candy was the “contraband” article they had brought to class. Some of the kids were interested in photography and told me about how they strove to learn white balance. Leslie had brought an electronic keyboard with her that day, and later, I listened to one of the kids play Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” on it. And somehow I had come full circle: I had played that exact same piece to my own son the night before. Suddenly, the distance between the inside and the outside seemed to vanish into thin air, a vast gulf turned into an imperceptible chimera.

It was from this process of realization and growing awareness that my project, Juvies, took shape.

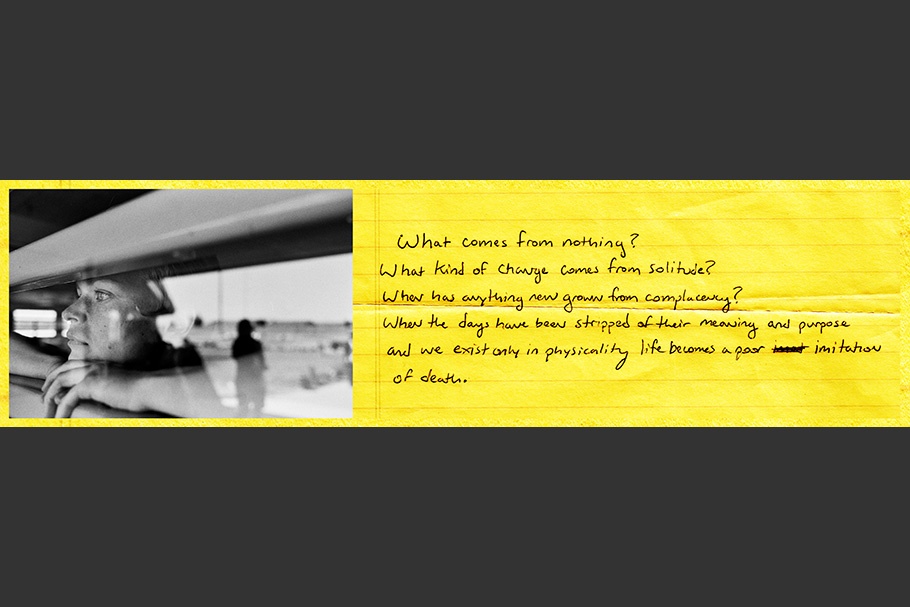

I found myself on a fence. I was partially inside and partially outside. And it was disorienting: I was in a privileged place that allowed the perceptions that existed in my head to be confronted by the realities I was witnessing in the closed and misunderstood world of incarceration. What I was seeing was also raising issues that would not give me peace. I can understand why Mayra might get life in prison for shooting her girlfriend from point blank range. But how could a combination of relatively minor charges result in the same life sentence for Duc, an 18-year-old who, despite having no prior convictions, was convicted in a shooting crime that resulted in no injuries and in which he did not pull the trigger? And why did Peter—a 17-year-old piano prodigy and poet—get 12 years in adult prison for a first time assault and breaking and entering offense? Why is the justice system so harsh on kids who clearly have potential?

I felt compelled to address these matters. I wanted to trace the physical and psychic contours of the world of these young people to see what they might reveal.

For the next couple of years, I tiptoed along this borderline: going in and out of juvenile hall and men’s and women’s prisons across the state of California photographing the young people and everything about their incarceration—the walls, the guards, the other incarcerated people, the yards, the bunk beds. I also photographed on the outside: the families and communities left behind as well as the courts and victims.

What emerged from these journeys is Juvies: a layered photographic narrative that merges my photographs of incarcerated young people with their own handwritten texts, giving each their unique voice to speak about their world. Juvies is not only a document, but also a query about perception. Do we know who these young people are and what we are doing to them?

—Ara Oshagan, June 2010