20090929-richards-mw16-collection-001

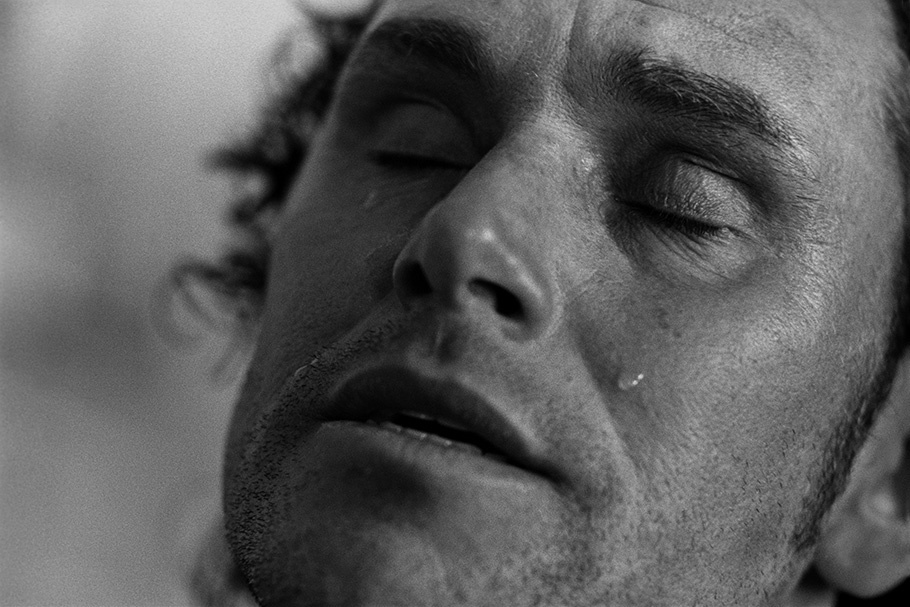

“I climb up to kiss him, to touch his hands, his fingers, his legs. I lay on top of the casket, on top of my son, apologizing to him because I did nothing for him to avoid this moment. Nothing.”

Carlos Arredondo. Roslindale, Massachusetts.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-002

“When they found Jose, the lower part of his body was still inside the Humvee, but the explosion had gone under his helmet and the left part of his brain was out in the sand.”

Nelida Bagley and her son, Jose. Roxbury, Massachusetts.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-003

"When we went after people, they were dead. No heads. Civilians were the casualties—people who just happened to be driving by, or sitting outside their homes.”

Mike Harmon and his grandmother. Brooklyn, New York.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-004

Returning National Guardsman. Butler, Pennsylvania.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-005

Tomas Young. Kansas City, Missouri.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-006

Dustin Hill and his daughter. Mineral, Illinois.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-007

Clint Keels and his mother. Laurens, South Carolina.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-008

Gail Ulerie and her son Shurvon. Richmond Heights, Ohio.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-009

Returning National Guardsman. Fort Dix, New Jersey.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-010

Boy visiting his father. Arlington National Cemetery.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-011

Tomas Young. Kansas City, Missouri.

20090929-richards-mw16-collection-012

Army Sgt. Princess Samuels. Mitchellville, Maryland.

Eugene Richards has worked as a photojournalist since the early 1970s. Among his numerous honors are a Guggenheim Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts grants, the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Award, and the Robert F. Kennedy Lifetime Achievement Journalism Award for coverage of the disadvantaged. Richards’s first publication was Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta (1973).

Richards’s subsequent books include Dorchester Days (1978), a portrait of the Boston neighborhood where he was raised; Exploding Into Life (1986), which chronicles his first wife’s struggle with breast cancer; Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue (1994), a study of the impact of hardcore drugs on three inner-city neighborhoods; The Fat Baby (2004), a collection of 15 textual and photographic essays; The Blue Room (2008), his study of abandoned houses in rural America; and A Procession of Them (2008), which confronts the plight of the institutionalized mentally disabled. His film, But, the day came, which chronicles the passage of an elderly Nebraska farmer to a nursing home, received the Best Short Film award at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival.

Eugene Richards

It was early 2006 and the war in Iraq was entering its fourth year. No weapons of mass destruction had been found. There were reports of sanctioned torture, of tens of thousands of injured and dead Iraqis, of more than 2,000 dead American soldiers, of a rising suicide rate among American military personnel, of deteriorating conditions inside U.S. military hospitals. All the while Congress and the media debated what the conflict was costing America in image and “treasure,” what the war was costing the president in his popularity ratings. And what had I, a veteran photojournalist, done? Not enough. Yet, quite hypocritically, I grew disapproving of other people’s silence.

One evening, returning home after photographing an antiwar demonstration with my son, I wrote what could loosely be called a poem. And in doing so, I found a focus for the work I needed to do.

War is personal

It’s my 17-year-old son Sam

that I’m thinking of when I say this

War is a reminder of all that we have

and all that we can lose

War is what happens when we fail

Tomas Young, 24, had been shot in the spine and paralyzed four days into his tour in Iraq. The morning I arrived at his Kansas City home, he had accidentally overdosed on his pain medications. As he struggled to speak with me, he slammed his body forward and back in his wheelchair, dropping his lit cigarettes into his lap. A week after my visit to Tomas’s home, I phoned him, concerned that I’d photographed him when he was perhaps most vulnerable. I was beginning to apologize when he interrupted me. “I don’t understand your concern,” he said. “The real problem is that we want to believe that people can go to war, then put it behind them. That happens, but not often.”

I continued working on what would become a series of photographic and textual essays focused on the lives of people profoundly affected by the war. I spent time with Carlos Arredondo of Roslindale, Massachusetts, who, upon learning that his Marine son had been killed in action, had a very public mental breakdown. Then I traveled to Mount Vernon, Ohio, to see Mona Parsons, who spent days trying to convince her son, who was home on leave, to not return to his Army unit in Iraq.

I attended the funeral service in Maryland for 22-year-old Army Sergeant Princess Samuels; spent close to a week in a VA Hospital in Roxbury, Massachusetts, documenting Nelida Bagley’s efforts to better care for her brain-injured son; met with Michael Harmon, a former combat medic, who was struggling to cope with his escalating posttraumatic stress disorder; traveled to Ramsey, Minnesota, to do a story on Clarissa Russell, a single mom whose Marine boyfriend had taken his life; visited Kimberly Rivera, who, after serving in Iraq, fled to Canada with her husband and children and now lives in fear of deportation.

In the end, I completed 15 stories of the many thousands that ought to be told.

—Eugene Richards, September 2009