20090929-woods-mw16-collection-001

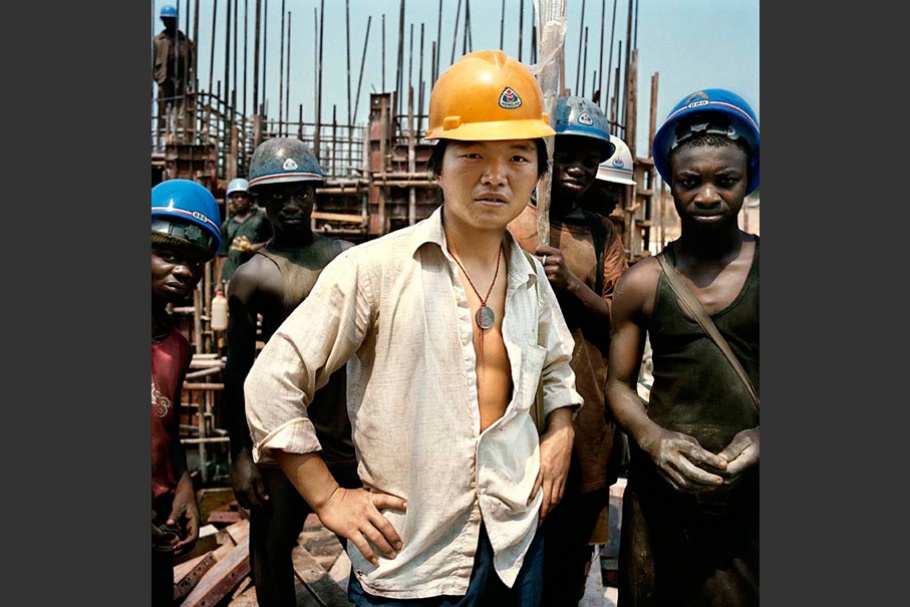

A Chinese worker of the China National Mechanical & Equipment Import & Export Corporation (CMEC), which in 2001 obtained a contract with the Congolese government. With its potential to produce 120 megawatts, this power plant will double the national production of electricity, giving light to a large part of the Congo. Four hundred Chinese technicians and qualified workers supervise a Congolese workforce of a thousand men who are each paid US$3 a day. Workers often leave as soon as they can find better paying jobs. This, in part, explains the delay in the dam’s construction, which Congolese authorities want completed in time for the country’s next elections. CMEC requires the Chinese workers to wear yellow hardhats and the Congolese to wear blue hardhats.

Imboulou dam, 200 km north of Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo. June 2007.

Paolo Woods, now based in Paris, ran a photo laboratory and gallery in Florence, Italy, before dedicating himself to documentary photography in 1998. His books include Un monde de Brut (with writer Serge Michel, 2003) covering the story of oil in 12 countries including Angola, Russia, Kazakhstan, United States, and Iraq; American Chaos (with Serge Michel, 2004) on the debacle in Afghanistan and Iraq; and Chinafrica (also with Serge Michel, 2007) documenting the spectacular rise of the Chinese in Africa. Chinafrica is translated and published in 10 languages.

Woods’s work regularly appears in GEO, Le Monde, Newsweek, Time, and many other international publications. He has had solo exhibitions in Austria, France, Holland, Italy, and Spain, and numerous group shows around the world. His photographs are in the French National Library, the FNAC Collection, and the collection of the Sheikh Saud Al-Thani in Qatar. Honors include the Alstom Journalism Award, the Amilcare Ponchielli Prize (awarded by the Italian Association of Photo Editors), and a World Press Photo award for his work in Iraq.

Paolo Woods

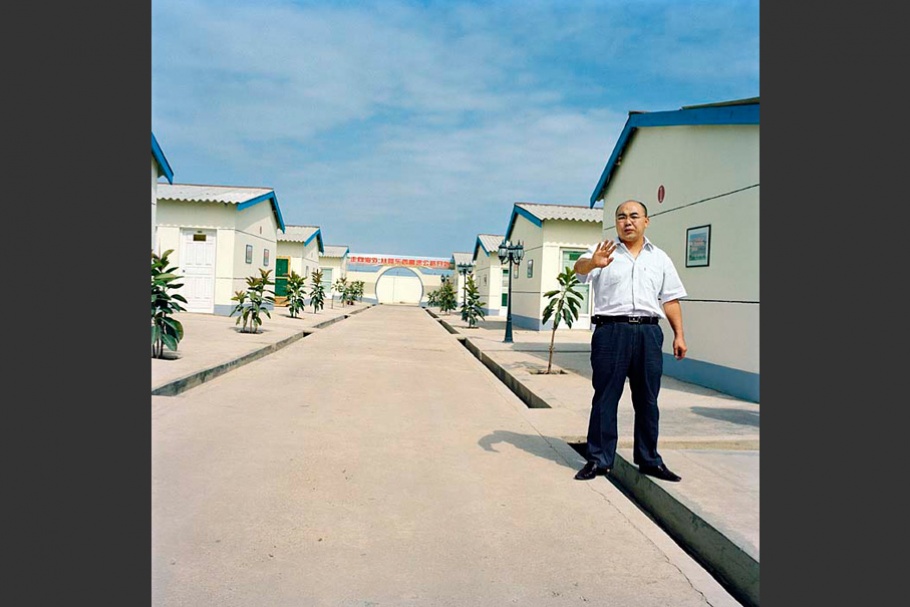

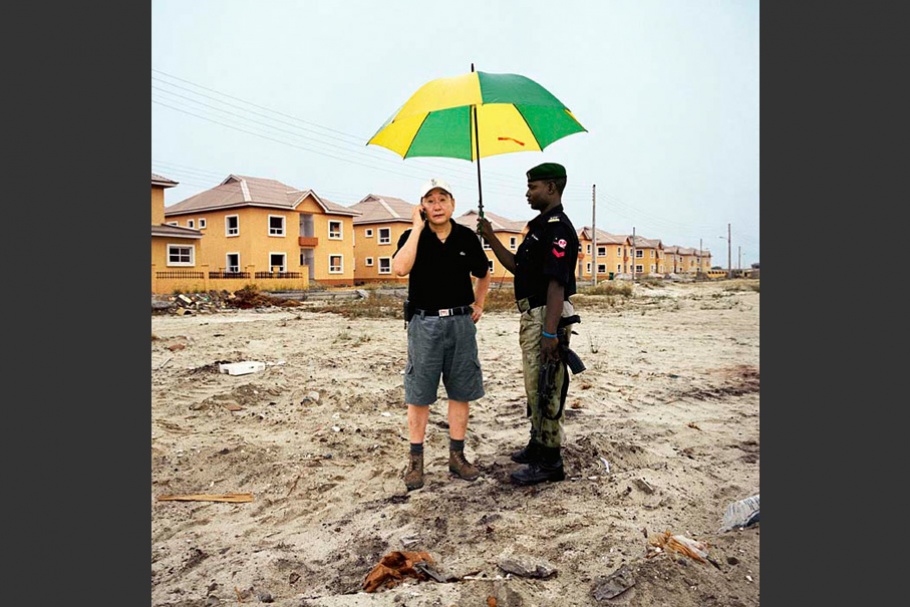

To quench its thirst for oil, its hunger for copper, uranium, and wood, the government in Beijing is sending Chinese state companies and adventurous entrepreneurs to Africa.

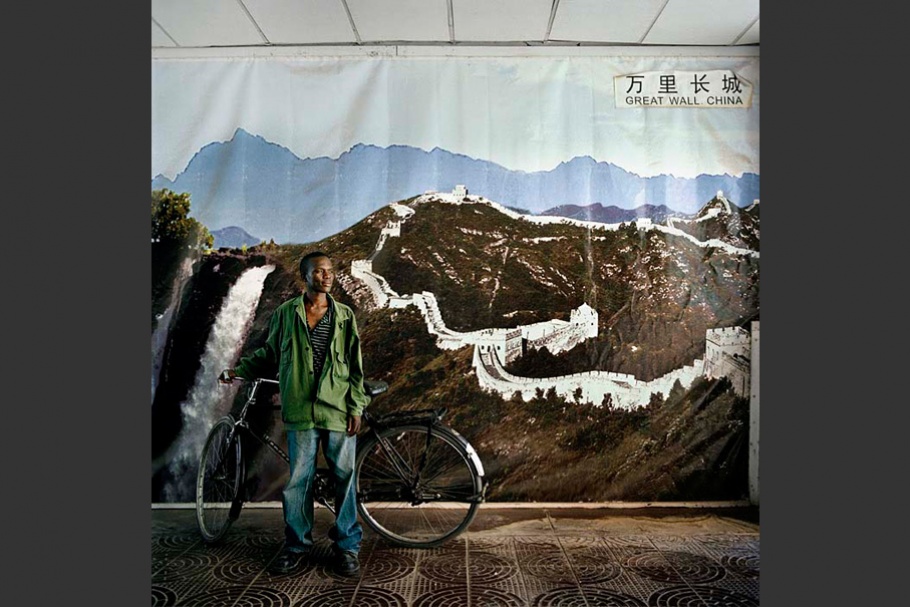

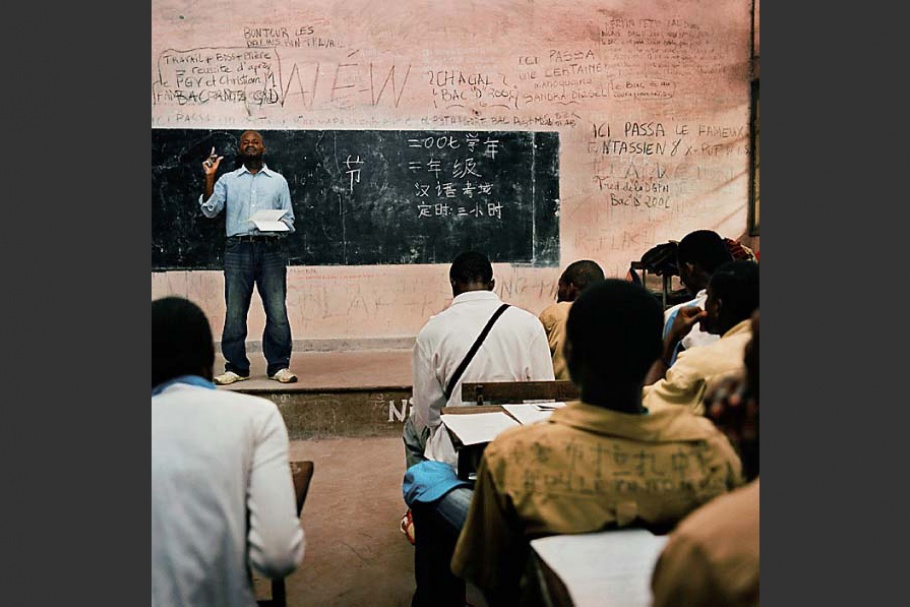

For the 500,000 Chinese who have emigrated in the last decade, Africa holds the promise of a 21st century frontier. Some have struck gold and run conglomerates spanning large regions of Africa, others are still selling cheap goods along the burning hot roadsides of some of the poorest countries in the world.

For many Africans, the arrival of the Chinese is perhaps the most important event since the old colonial rulers left decades ago. The Chinese do not act like the former colonialists. They build roads, dams, and hospitals in exchange of raw materials—and they win over the people. They speak of neither democracy nor transparency—and they win over the rulers.

I have documented the Chinese stirring up Africa, accompanying them along the railroads of Angola, through the forests of the Congo and the karaoke bars of Nigeria.

From the barren countryside of Central China to the leather armchairs of African ministries, I have tried to capture the quest of the Chinese who came to Africa to make their fortunes and who invested their lives and their money in a continent that many in the West have long considered fit only for handouts.

As I worked I tried to develop a visual language that mixed the content of classic photojournalism with portraiture photography but that also played with elements of colonial imagery and the propaganda photography so dear to the Chinese establishment.

These are rare images. Getting access to the Chinese in Africa was the most difficult assignment I have ever undertaken. The Chinese want to keep a low profile on their business activities in Africa. I hope these photographs portray a phenomenon and a new dimension that is not just a product of globalization but also its ultimate realization.

—Paolo Woods, September 2009