20090929-deluigi-mw16-collection-001

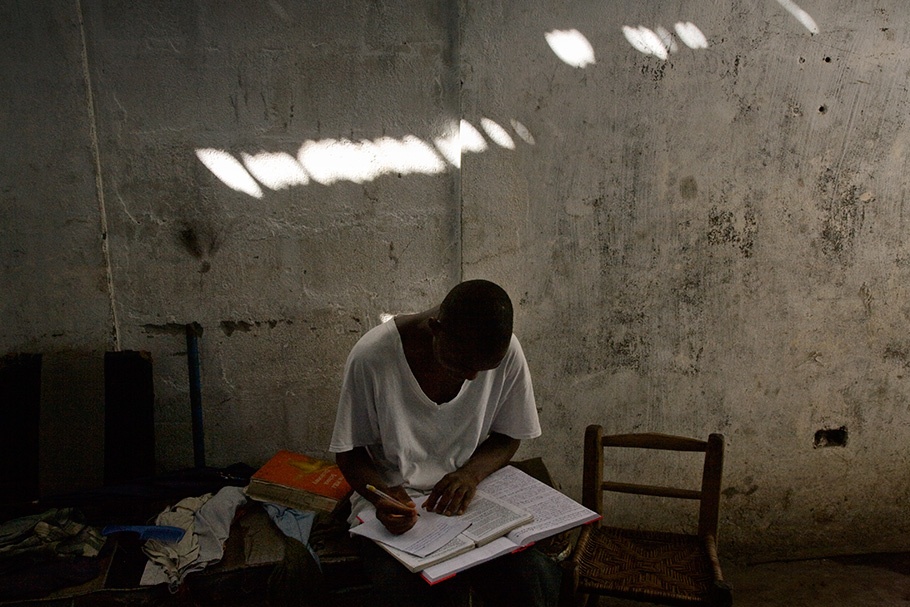

A child works on his studies.

Tortoise community, Monrovia, Liberia. October 2008.

20090929-deluigi-mw16-collection-002

Laundry dries in a villa.

Tortoise community, Monrovia, Liberia. October 2008.

20090929-deluigi-mw16-collection-003

A former child soldier rests on the wall of a damaged building.

Tortoise community, Monrovia, Liberia. October 2008.

20090929-deluigi-mw16-collection-004

A view of the Atlantic Ocean from the coastline.

Tortoise community, Monrovia, Liberia. October 2008.

20090929-deluigi-mw16-collection-005

A wedding dress is laid out to dry near a destroyed home.

Tortoise community, Monrovia, Liberia. October 2008.

20090929-deluigi-mw16-collection-006

A view of the Atlantic Ocean is seen from a demolished villa.

Tortoise community, Monrovia, Liberia. October 2008.

20090929-deluigi-mw16-collection-007

Children from the Tortoise community play along the Atlantic Ocean coastline.

Monrovia, Liberia. October 2008.

20090929-deluigi-mw16-collection-008

A soldier's helmet lies in the street.

Tortoise community, Monrovia, Liberia. October 2008.

Stefano De Luigi has worked as a professional photographer since 1988. In 1999, in collaboration with Médecins Sans Frontières, De Luigi portrayed the health conditions of tuberculosis prisoners in Siberian prisons. His project about the world of pornography was published as a book, Pornoland, and exhibited in France and Italy. From 2003 to 2007, in collaboration with CBM Italy, De Luigi worked on Blindness, which will be published as a book. Cinema Mundi, about alternative cinematography scenes, became a short film, shown at the Locarno Film Festival in 2007. De Luigi has received the Marco Bastianelli Prize, a W. Eugene Smith Fellowship Grant, two World Press Photo awards, and an honorable mention from the Leica Oskar Barnack Award.

Stefano De Luigi

There were all kinds of stories told about the war that made it sound as if it was happening in a faraway and different land. It wasn’t until refugees started passing through our town that we began to see that it was actually taking place in our country. Families who had walked hundreds of miles told how relatives had been killed and their houses burned. Some people felt sorry for them and offered them places to stay, but most of the refugees refused, because they said the war would eventually reach our town. The children of these families wouldn’t look at us, and they jumped at the sound of chopping wood or as stones landed on the tin roofs flung by children hunting birds with slingshots…. Apart from their fatigue and malnourishment, it was evident they had seen something that plagued their minds, something that we would refuse to accept if they told us all of it.

—A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, Ishmael Beah

Sometimes there is a chance to recover innocence. Sometimes it is not too late, and a little story about special people in a special place can become a flame to see in the dark.

During Charles Taylor’s dictatorship in Liberia, the place in the photographs, this beautiful spot overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, was used to torture opponents, traitors, and spies. The sound of the sea covered the screams during interrogations.

In 2004, after Taylor was gone and 15 years of civil war had ended, a group of former child soldiers came to live among these ruined villas, where the richest families in Monrovia had once vacationed. Used by both rebel and government forces, they were involuntary actors in this bloody conflict, war survivors trying to find a future in a country still poor and desperate. These are children who turned adult too soon, and now are joined together to survive, to forget violence and death.

The young people have formed their own community, the Tortoise community, and returned to a simpler life, making their own rules, their own churches. The community has learned how to use the beach sand to build bricks and how to catch the lagoon’s catfish to sell at the market. Traces of normal life are returning.

Isolated from the world in a small lagoon, their lives flow a few hundred meters from one of the main arteries of the Liberian capital. Yet, the Tortoise community seems suspended in time.

Protected by the reassuring roar of the waves, the Tortoise community’s members are trying to rebuild their own imagined horizons. In a community that lives day to day, hope is eternal. A small improvement, a bitter sweetness or a broken smile, is a good omen, a happy beginning.

—Stefano De Luigi, September 2009