20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-001

At the start of the revolution, Nepal was the only Hindu kingdom in the world. The Shah dynasty established itself by conquering and uniting the Himalayan nation more than two centuries ago, enshrining their power through the belief that the kings were the reincarnation of the god Vishnu. Their reign and organization of the country rested on the strict observance of the Hindu caste system.

Nepalgunj, February 2004

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-002

In 2005, on the eve of the anniversary of the start of their “People’s War,” a Maoist guerrilla raises the communist flag over the rebel-controlled village of Rukumkot.

Rukum district, February 2005

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-003

The Maoist army swelled its ranks with women and low-caste recruits, the bottom rungs of Nepal’s oppressive social hierarchy. In impoverished feudal villages, many saw joining the rebels as the only path to modernity and respect.

Gairigaon village, Rukum District, February 2005

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-004

Thousands of families fled their homes as the Maoists expanded their control over rural Nepal. Most villagers that I spoke with complained of being caught between both sides. Maoists coerced peasants to attend propaganda programs and contribute part of their rice harvests to feeding the rebel army. Royal Army troops later swept through villages, killing or “disappearing” suspected collaborators.

Kirin Khola I.D.P. camp, June 2005

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-005

Over 12,000 people were killed in a decade of civil war. This police officer, whose body is being prepared for cremation, was killed during an ambush by Maoist rebels.

Kathmandu, January 2006

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-006

At the height of the unrest, protesters gathered on the outskirts of Kathmandu and tried to overwhelm security forces guarding the city’s perimeter. Three protesters were shot dead by police at this particular confrontation.

Kathmandu, April 2006

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-007

In 2006, mainstream political parties joined forces with the Maoists against the monarchy in mass street protests. The government responded to the unrest by banning all political gatherings inside Kathmandu. Many demonstrations turned violent. This protester, carrying a police baton, helped set fire to government offices.

Kathmandu, April 2006

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-008

A photograph of King Gyanendra falls into a ditch at the height of protests against his rule.

Kathmandu, April 2006

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-009

Protesters who penetrated the city center were beaten mercilessly by security forces. As his final effort to stop the protests in April 2006, King Gyanendra declared round-the-clock curfews for several days in a row, threatening that anyone caught outdoors would be shot on sight.

Kathmandu, April 2006

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-010

The people of Kathmandu eventually took to the streets in defiance of the curfew orders. Faced with the overwhelming crowds, King Gyanendra backed down and relinquished his grip on executive power on April 24, 2006.

Kathmandu, April 2006

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-011

Inspired by the revolutionary strategies of Mao Tse-tung, hardline leftists in Nepal formed the People’s Liberation Army and vowed to topple the monarchy.

Nawalparasi, October 2007

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-012

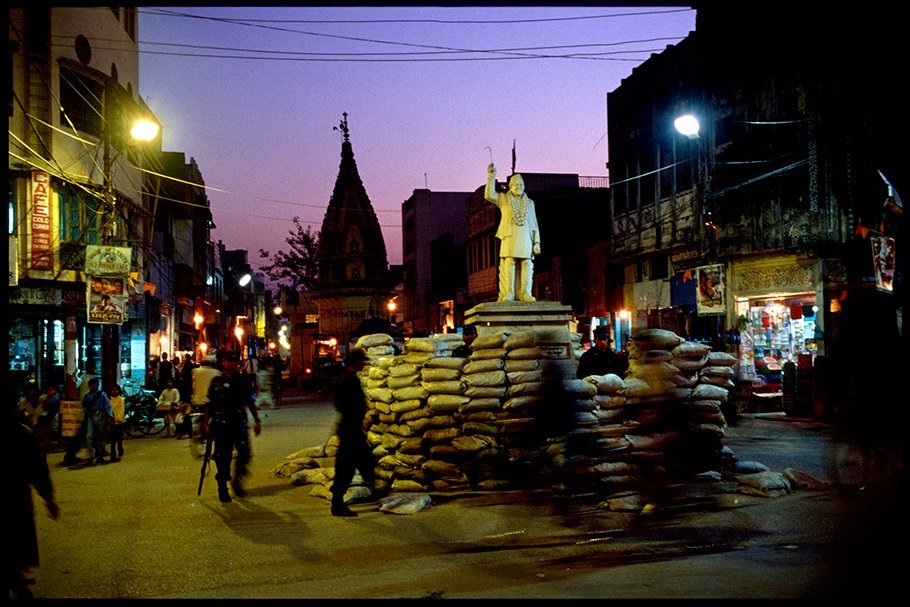

Security forces became a constant presence around the royal palace and near symbols of the monarchy up until the King’s final days as ruler of Nepal.

Kathmandu, May 2008

20090929-vanhoutryve-mw16-collection-013

After the successful protest movement, the Maoists agreed to a ceasefire and to participate in elections. They won the biggest share of the votes, and chose their guerrilla chief, Comrade Prachanda, to be the prime minister. Maoist supporters celebrated by lighting candles in the shape of a hammer and sickle on May 29, 2008, the day that the new parliament voted to abolish the monarchy and declare Nepal a federal republic.

Kathmandu, May 2008

The son of a Belgian diplomat, Tomas van Houtryve spent much of his childhood in California. Initially a student in philosophy, he discovered his passion lay in photography while enrolled in an overseas study program in Nepal. After graduation, he started his photographic career in Latin America. He returned to Nepal in 2004 to document the growing Maoist rebellion.

Van Houtryve has photographed conflict and human rights issues in some of the most inaccessible places on earth, from North Korea to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. He has received numerous international awards for his coverage of global contemporary issues including the Visa pour l’Image City of Perpignan Young Reporter Award, Second Place Pictures of the Year International Magazine Photographer of the Year, and most recently, an Alicia Patterson Fellowship.

Solo exhibitions of his work have been shown in France and Italy, and his pictures appear regularly in leading international publications, including Newsweek, the New York Times Magazine, TIME, GEO, Stern, Le Figaro Magazine, Le Monde, and National Geographic.

Tomas van Houtryve

A desire for equality, freedom, and dignity surfaces in all societies. This is especially true in Nepal, where poverty is deeply entrenched, and where until recently the political system resembled the reigns of medieval Europe. For more than 50 years, various attempts at democratic and socialist reforms in Nepal ended in disappointment. Then in 1996, a band of rebels inspired by the teachings of Mao Tse-tung declared the beginning of the “People’s War.” Villagers, who had lived for generations under a feudal caste system controlled by kings considered the reincarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu, were now rounded up and marched to propaganda programs to learn Marxist-style equality.

When I first visited Nepal as a student in 1997, I was captivated by the Himalayan panoramas and Eastern spirituality. But I quickly saw the darker side of this society, in which women and “untouchables” were denied education, political rights, and social status. By the time I returned to Nepal in 2004, the Maoist guerrilla movement had spread across the country and unnerved the ruling elite. Their camps were hidden in the rural hinterlands. They usually attacked at night, capturing police outposts with swarms of peasant soldiers brandishing ancient rifles. My curiosity about the rebels was driven by empathy for their proclaimed desire to uplift the subjugated masses, and tempered by trepidation and skepticism of their communist tactics.

Initially, I set out into the rebel-controlled territory on my own. With knowledge I had gained as a student, I eventually penetrated the underground movement. Up through 2008 I dedicated most of my energy to documenting the conflict in Nepal.

In 2006, the revolution switched from guerrilla warfare in rural areas to violent street protests in the cities. Mainstream democratic political parties, which the king targeted in his crackdown on dissent, ultimately formed a tenuous alliance with the Maoists. Their strategy was to dislodge the monarchy through mass street protests. The joint movement worked, and in 2008 the country finally held democratic elections. The results ended over two centuries of autocratic rule by abolishing the monarchy, and dissolved the communist insurgency that had killed more than 12,000 people.

—Tomas van Houtryve, September 2009