20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-001

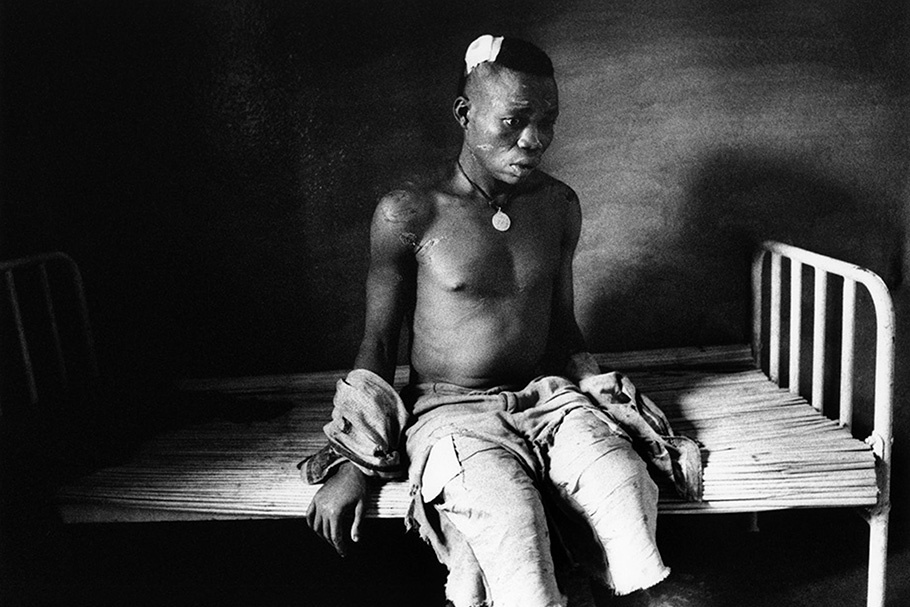

A soldier from the Lendu militia (the Lendu are one of the warring ethnic groups in eastern Congo) in a makeshift hospital in Mongbwalu. Captured and beaten by the local population, he now waits for news of his future.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-002

Soldiers demonstrate in Bunia.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-003

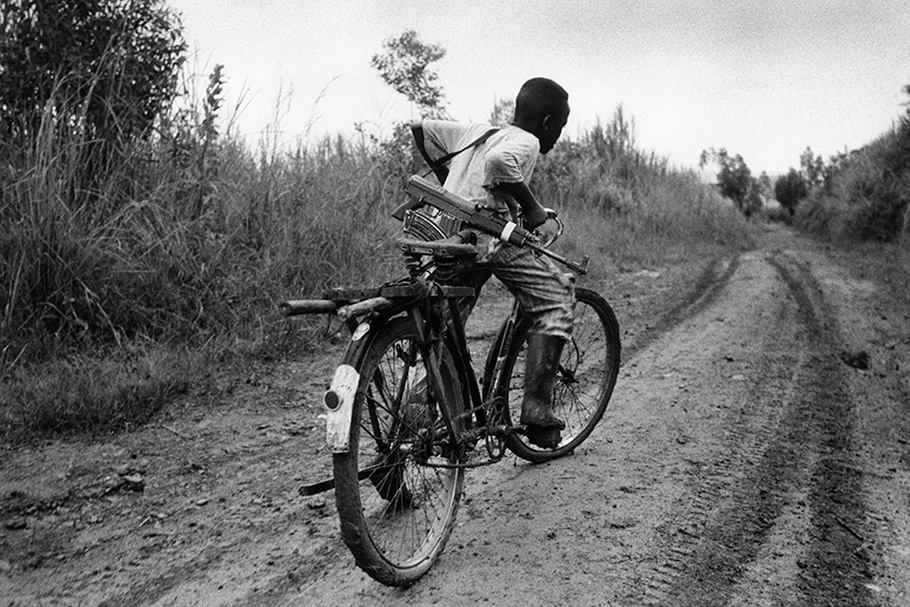

A child soldier rides back to his base in Ituri.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-004

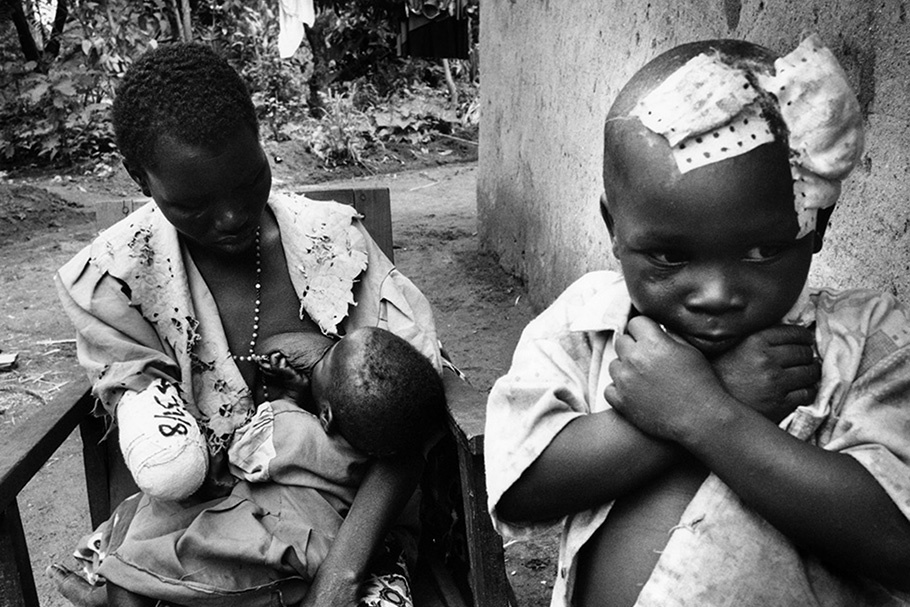

A child soldier waits in a camp for news of his next deployment. Children are used on all sides of the conflict in Ituri.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-005

Catherine, too afraid to stay in the hospital for fear of being attacked, is taken back to the bush after being given basic treatment in Dro Dro. Two weeks previously, fourteen people were killed in their beds in the hospital. She was attacked by Lendu soldiers who tried to cut off her leg with a machete. She survived, but three members of her family were killed.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-006

Maria, a mother of three, lost her arm defending her children in Nizi. After the soldiers amputated her limb, they ate flesh from it.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-007

The body of Sakuru Lisi, the child of a goldminer in Mungwalu who died of anemia brought on by malaria, is bathed before being buried. Because the region is at the center of the battle for gold resources, medication and treatment for the sick are not available.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-008

The coffin arrives for the funeral of eight-month-old Sakuru Lisi.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-009

The family says their final prayers at the funeral for Sakuru Lisi.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-010

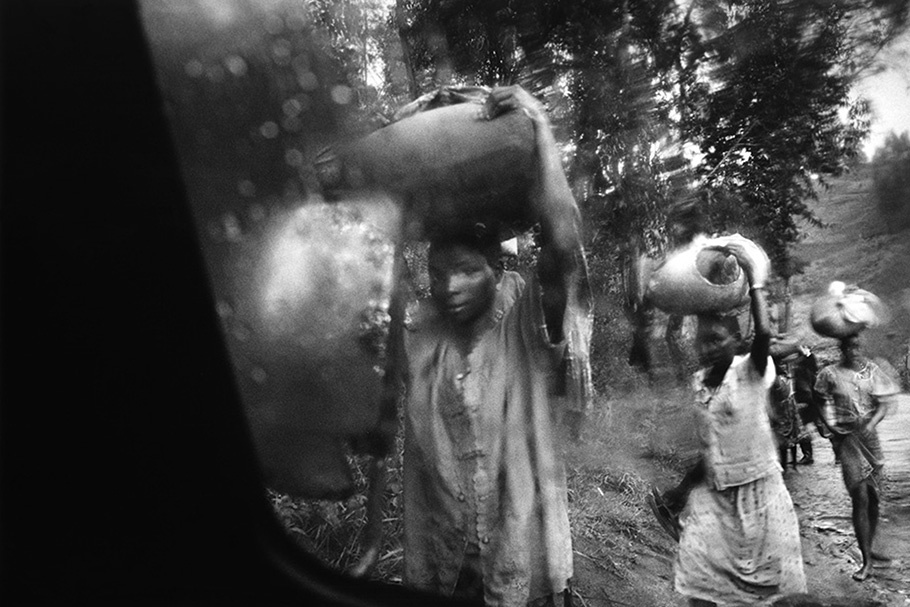

Refugees flee south after a rebel attack on Bule and Fataki. The attacks were to gain control of the mineral rich areas.

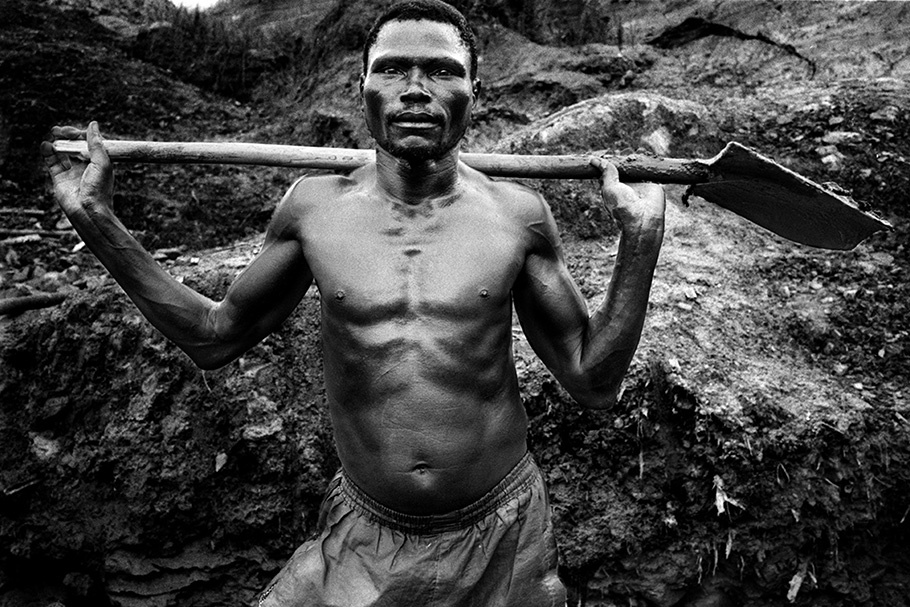

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-011

An ex-combatant in Mongbwalu. Many miners are soldiers or ex-soldiers who profit from exploitation. Warlords use the profits from gold to fund weapon purchases.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-012

Shifting the gravel.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-013

The silhouettes of soldiers packing up their tools at the end of their shift. They will be replaced by another shift that works through the night.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-014

Measuring the amount of gold dust at the end of the day. Most miners work for warlords who pay them one dollar a day.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-015

Shifting the earth.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-016

A family at work.

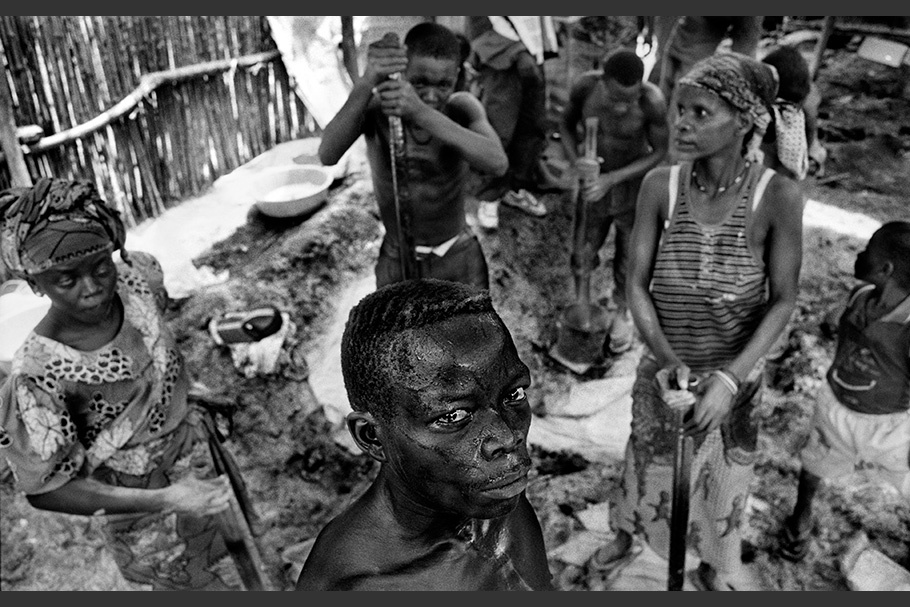

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-017

Miners pound the gold rock to produce gold dust. It can take up to eight months before any significant gold deposits are extracted.

20051201-bleasdale-mw11-collection-018

Digging the pit by hand.

Marcus Bleasdale graduated from the University of Huddersfield in England in 1990 with a BA in Economics and Finance. In 1999, he received a postgraduate diploma in Photojournalism from the London College of Printing.

He has spent six years covering the brutal conflict within the borders of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The resulting photographs were published as the book One Hundred Years of Darkness, which was recognized as one of the best photojournalism books of 2002 by Photo District News.

Over the years, Bleasdale has received several first prizes in the Picture of the Year and National Press Photographers Association awards. In 2004 he was awarded UNICEF Photographer of the Year Award, the 3P Photographer Award, and a grant from the Alexia Foundation Grant. In 2005, he was awarded a distribution grant from the Open Society Institute for his work with Human Rights Watch. His work is published widely in the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States in publications such as the Sunday Times Magazine, Telegraph Magazine, GEO, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, and National Geographic.

Marcus Bleasdale

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has the potential to be one of the richest countries in Africa. It has immense mineral reserves, many of which are unique to the region; the land itself is highly fertile, giving the DRC the opportunity to be a significant exporter of food; and the Congo River is capable of providing sufficient hydroelectric power for all of southern Africa.

Yet, with a per capita gross domestic product of only $110 the country is the poorest in the region. Since the war began in 1998, the country has fallen 28 places in the UN Human Development Index to 168 out of 177. Over half of the 5 million people living in the DRC survive on less than $1 a day.

Until 2004, as many as seven nations were fighting within the DRC’s borders. The conflict, arguably the murkiest and deadliest on earth, has been in large part about natural resources. The war began in 1998, when military forces from Rwanda and government forces from Uganda crossed the border and began to vie for control of eastern DRC’s minerals. From these first months, resources helped define military strategy. Congolese rebels and Rwandan troops laid siege to mining towns for gold, diamonds, coltan (for laptops and mobile phones), and more recently cassiterite (used in making tin), among others. Soon,Ugandan government forces and other Congolese rebel forces did the same.

The looting and killing in the DRC has changed very little over the past centuries. The goods may be different, but the methods and motives remain the same. According to the International Crisis Group, 1,000 people die in the Democratic Republic of Congo every day, and approximately 4 million have died as a result of the war. For every person who is killed violently, 62 more, mostly women and children, die of completely avoidable causes: diarrhea, malnutrition, malaria, and cholera, to name a few.

An October 2002 report released by the UN named 85 multinational companies guilty of illegally exploiting the country’s natural resources. But years later, the activities that the UN panel expressed concern over continue, and so does the conflict, as stated in a recently released report from Human Rights Watch.

Mining causes irreparable damage to society. The villages are stripped of their agricultural basis, as most villagers choose to work in the mines rather than labor for low agricultural returns. Cholera, malaria, and hemorrhagic fever are regular occurrences in mining areas.

After successive waves of fighting and seven years of war, the people living in the mineral-rich mining towns of eastern Congo are some of the worst off. There are no hospitals, no roads, and no NGO or UN presence—it is simply too dangerous to work there. The inaccessibility of the mining zones and the reluctance of international agencies to operate in these areas allow devastating disease to spread to epidemic proportions.

Thousands, mostly children and women, die from a lack of health care and sanitation.

This fundamental breakdown of the social structure of African societies, fueled by the west’s desire for minerals and gems, is as damaging to human life as the fighting itself.

—Marcus Bleasdale, December 2005