20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-001

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Marlena and Jimiya, 12 years old.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-002

Camp Heartland, July 2002.

Fola's memorial service.

Fola

July 19, 1981–July 21, 2002

As told by Tanya, 18 years old.

I'm going to miss her so much. I miss her laugh, I miss her voice, I miss her crazy self. Her Backstreet-Boys-singing, N-Sync-dancing self. She was my best friend in the whole world. You always become friends with people you connect with. Obviously if you have it, and they have it, you have a connection. I've lost too many friends, and it's just really hard.

She was lucky for awhile. She didn't have T-cells for a very long time. Her viral load was very high. She was lucky she made it as long as she did. Two days after she turned 21, that's when she passed away. I was just so happy she made it to 21. I never had a friend like her, and I probably never will again.

I haven't talked to her in so long because she couldn't talk, she couldn't walk, she couldn't move. She had a feeding tube, and she couldn't talk for months. There was always that hope that she would call me and curse me out for not calling her. That would be so cool, but it just didn't work out. I felt very sorry for her because she was in so much pain all the time, and she couldn't tell you.

It's painful when they die if you have it too because you think that you might end up that way. And that's hard. I saw her a month before she died, and I know what she looked like.

I don't want to suffer. I really don't want to suffer. I've seen it too many times, and I don't want to put my family through it. I don't want to put myself through it either.

I miss her already, and it hasn't been a week yet, you know what I mean?

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-003

Camp Heartland, July 2002.

Stacey, 14 years old.

My mom and my dad, they did cocaine and heroin, and that's how they got it. It passed through the blood stream and into my body, and I got it when I was born. A little while later, my mom and my dad died from it. Well, my mom did, but not my dad. My dad died from drugs.

When I was born, the doctors said I was going to live until I was two. Well, they were wrong. I am now 14. I'm really happy that I lived, and I didn't die.

If people want to disrespect me, that is their fault. Because they didn't really get to know me, they just know my disease.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-004

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Donte, 9 years old.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-005

Camp Heartland, July 2002.

A 10-year-old girl lingers over her HIV medications. The large pills are hard to swallow, especially for younger children. The side effects include headaches, vomiting, and even nightmares, so many children hide the pills or flush them down the toilet, ignoring the danger of having their virus mutate and become resistant to the treatments.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-006

Camp Heartland, October 2004.

Tia, 14 years old.

I think about dying a lot, I guess.

Sometimes, if I'm not doing anything, all of a sudden it just comes into my mind. I don't know why. When you're little, you don't think about it, you don't know what it means. As you get older, you learn more facts, and you think about certain stuff more often. It gets harder, I think, to try to cope and understand what your body is going through, what you're going through.

I distract myself. I try to sleep, or I talk on the phone or something. I just wanna get it out of my mind.

If you can have sex, have it—as long as it's safe, and as long as you tell the other person. Go ahead, that's what I say.

I tell most of my friends. It's like you don't wanna lie no more. It was easier to lie when I was little.

I enjoy my life. I barely get sick. My viral load is low, so I'm doing good. If you met me, you wouldn't think I have it. Everybody knows me as goofy, wild, friendly, loveable Tia.

I want to make sure that everybody understands what kids that are infected or affected by it are going through. They look at life in a different way than most people do because they don't have a lot of time to live, and they're gonna make the most of it.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-007

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Lesley, 12 years old.

I'll tell you a story. When I was in the second grade, there was a girl named Kailey in my class. Kailey was told by her mother that she wasn't allowed to hold my hand because I had the disease. We were going outside to play Duck-Duck-Goose one day, and I wanted to be her friend 'cause she was new. I told her that I had HIV, and she told her mom that night.

"I don't want you hanging around that girl," her mom told her. "I don't want you holding hands or touching that girl." And then the next day, when we played Duck-Duck-Goose, whenever I went to hold Kailey's hand to make the circle, she said, "Oh, I don't want to touch your hand. My mom told me I can't."

That's where one story ends, and then there's another story.

I was really little, I was probably seven or eight, and I just came out of the hospital. I had an IV in my arm because they had to give me more medicine. I had been in the hospital two months, but I was doing all right, so they sent me home because I was getting tired of the hospital.

We were going to church that morning because there was an Easter egg hunt. The pastor found out I had an IV, and said he didn't want me to go to that church. My mom is HIV-positive, and my step dad has full-blown AIDS, and so the pastor kicked us out of the church. It was Easter Sunday, and I felt like I was left out. I had a really, really, really best friend at the church, and I haven't seen her since. I remember her name was Anna. Yeah, I remember that.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-008

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Boy with his HIV medication.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-009

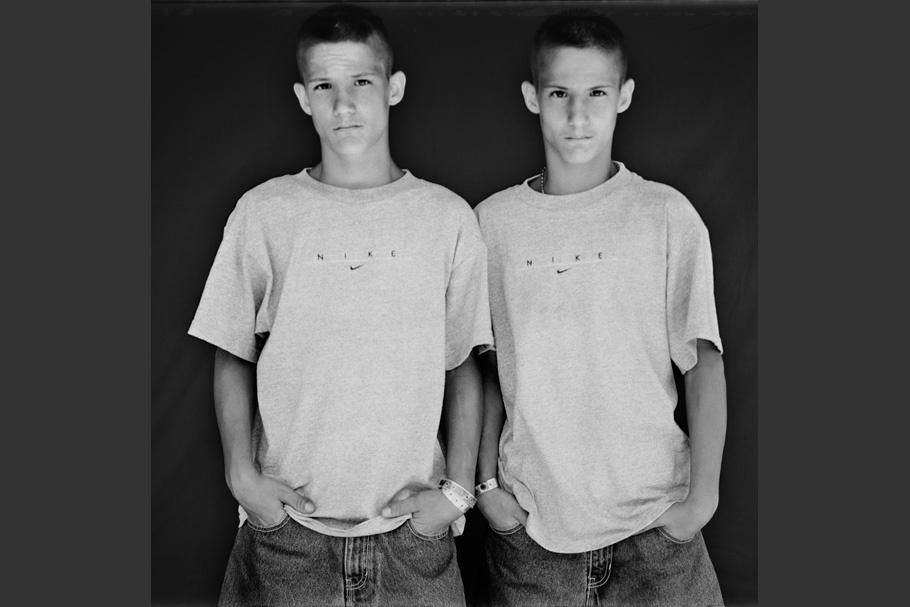

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Sheridan and Shane

Photographed on their fourteenth birthday

Sheridan: At school, when people go around talking about my mom, I just start fighting them. That's why I'm always out of school, 'cause I always fight so much, and that's one thing I gotta stop doing. I tell them, please don't because I don't want to hit you. So I walk away now, I guess. They'll say: "Your mom is so ugly. She's laying around the house so much." She has depression, too, on top of HIV. They'll say: "She's too lazy. She's not even doing anything for you." I help her a lot, cleaning the house and other things. When people say that, I'm like: "You don't know how it is 'cause you don't live with people like that."

Shane: Everybody else got their mothers making their beds, doing their laundry, the dishes, cooking for them, and taking care of them, but we have to do that by ourselves sometimes. But once in a good while my mom will get up and cook dinner and do stuff for us.

Sheridan: And they have fathers, too. We don't. I think he left before we were even born.

Shane: If you tell people, they say don't touch me, get away from me, leave me alone.

Sheridan: Or if you have a girlfriend, they'd be like: "Oh my God, you never told me your mom had it." And then they overreact, and say: "Oh my God, you have it, too." But I don't have it because my mom got it after we were born. And then they're like: "You still could've got it from kissing and hugging them." But they're all wrong. You can't get it from hugging, you can't get it from kissing, and you can't get it from saliva—unless you drink two gallons of the person's saliva and that's gross.

Shane: In school, there's some health teachers that say: "You can get HIV from kissing someone." I told them that it's not true. My nurse said you can only get it from unprotected sex, blood, breast feeding, being born with it, and open wounds. That's the same thing as blood though.

Sheridan: Needles.

Shane: And sharing needles. That's it.

Sheridan: When my mom had HIV, they were gonna try to take me and Shane away. They didn't know a lot about HIV when she got it. Then they thought we can get it from her when she sits on the toilet and then we sit on the toilet, or we can get it from sharing spoons. So my mom had to go through a lot.

Shane: If they take us away when we are little, it would be like taking another piece of her away, and she'd feel more tired and sick, and then she'd probably end up killing herself. Or dying.

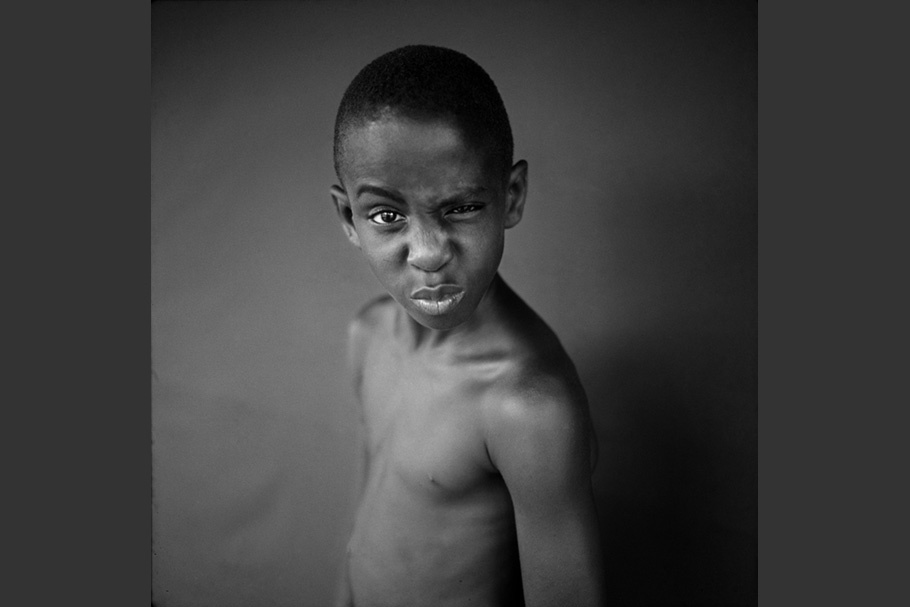

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-010

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Cardell, 12 years old.

When I was nine, my mom said: "Mommy is very, very sick. She has to take her medicine. So you take care of mommy and make sure she takes her medicine."

Me: "Okay, mommy."

When I was 10, she said: "When you were nine, I left out a little bit. Mommy has a bad, bad sore, and she needs a lot of help to get rid of it."

I said: "Okay, mommy.

When I was 11, she said: "Mommy has a really, really bad problem."

I said: "Okay, mommy."

When I was 12, she said: "Mommy has a disease."

And I said: "All right, mommy has HIV. Straight up. There ain't gonna be any 'Okay, mommy' no more. It's going to be: 'Yo, you gonna live, and that's that.'"

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-011

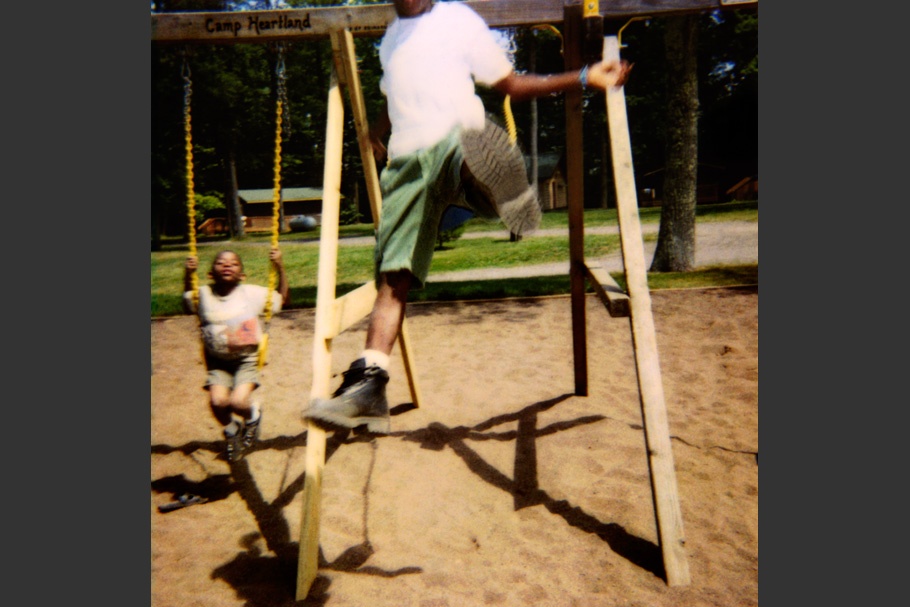

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Swing set.

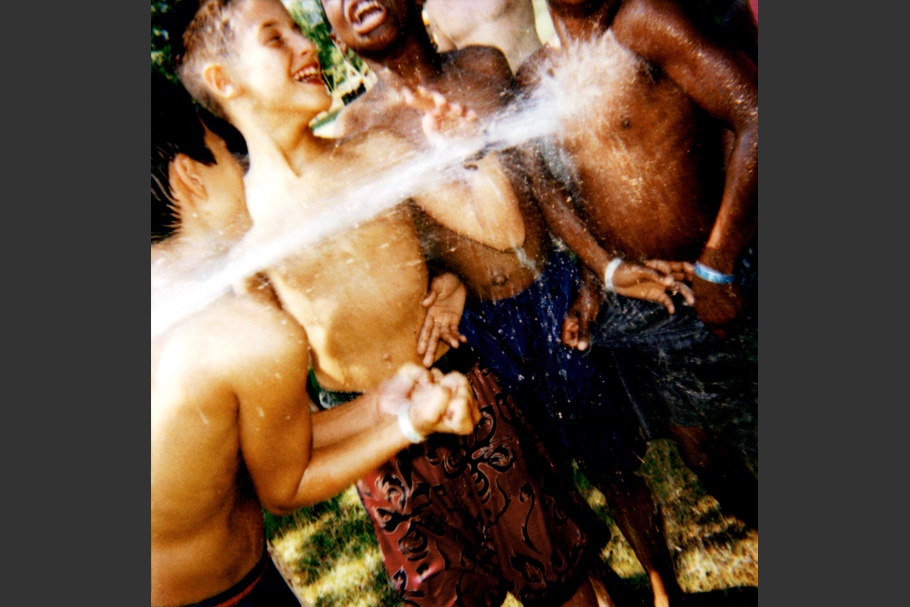

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-012

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Steven, 12 years old.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-013

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Cabin Six.

20051201-heinemann-mw11-collection-014

Camp Heartland, July 2001.

Steven, 12 years old.

After growing up in Germany, Katja Heinemann has spent the past 14 years in the United States and currently lives in Brooklyn, New York. As a documentary and editorial photographer, her work focuses on intimate portrayals of people and everyday life in America, exploring issues of women's health and body consciousness, immigration, and, more recently, American patriotism and militarism after September 11.

Since the summer of 2000, Katja has been working on the new media documentary On Borrowed Time, which chronicles the lives of children and teenagers who have grown up with HIV/AIDS in the United States. The resulting multimedia website by Time.com won several awards in the 2002 Pictures of the Year and National Press Photographers Association competitions. Her photographs and interviews with the children of Camp Heartland were published as a book, Journey of Hope, in the spring of 2005.

Katja was a contributor to Chicago's independent documentary project, Chicago in the Year 2000, and her photographs have been included in the anthologies Here is New York, which documents September 11, and Pandemic: Facing AIDS. Her editorial work has appeared in Time magazine, U.S. News & World Report, Stern, the Chicago Tribune Sunday Magazine, and French Marie Claire, among others. She is represented by Aurora Photos.

Katja Heinemann

With improved medical treatments, HIV-positive children in the United States are now reaching their teenage years. But the majority of young people suffering from HIV/AIDS cannot talk about the illness outside their homes—and sometimes not even within their families—because of the stigma attached to the disease. Many feel isolated from their peers as well as adults. They do not know others who are experiencing the emotions that accompany illness, secrecy, and loss. While new treatments bring hope, a cure remains elusive, and children living with HIV/AIDS have to learn to cope with toxic, often experimental, medical regimens. School poses a separate set of problems, from needing to be secretive and hiding medications to missing classes because of illness and visits to the doctor. And as the children grow older, the already difficult process of coming of age sexually is further complicated by the sexually transmittable nature of their illness.

On Borrowed Time explores the impact the disease has on young people. The photographs were taken at Camp Heartland for Children Affected by HIV/AIDS, where a safe atmosphere and feeling of acceptance enable the children to share their stories and find support. Both HIV negative children, who suffer from the impact that the illness has on their families, and HIV positive children attend the camp.

Of the approximately one million people living with HIV in the United States, an estimated 10,000 are children who contracted the virus from their mothers or through tainted blood transfusions. Eighty-five percent of HIV-positive children are Black or Latino; most live in urban areas. HIV/AIDS in the United States remains a disease of poverty.

Many Americans now view HIV-infection as another chronic but manageable illness, unaware of the overwhelming physical and psychological consequences that accompany the disease even in a nation that can afford to treat those who have contracted the virus. Contrary to the widespread assumption that the epidemic has been brought under control, HIV-infection rates in America have remained consistent over the past two decades at 40,000 new infections each year. And in certain segments of the population HIV/AIDS is actually on the rise, with the fastest growing rate of new infections among minorities and young people between the ages of 15 and 24.

Continued, in-depth documentation of the AIDS epidemic in western, industrialized nations such as the United States is crucial. No amount of medical technology can address the social causes that perpetuate the cycle of new infections—causes that include the stigma toward people with the illness and the lack of public education and prevention efforts. Only through an increased awareness of the psychological causes and effects of HIV transmission will we be able to combat this illness successfully.

—Katja Heinemann, December 2005