20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-001

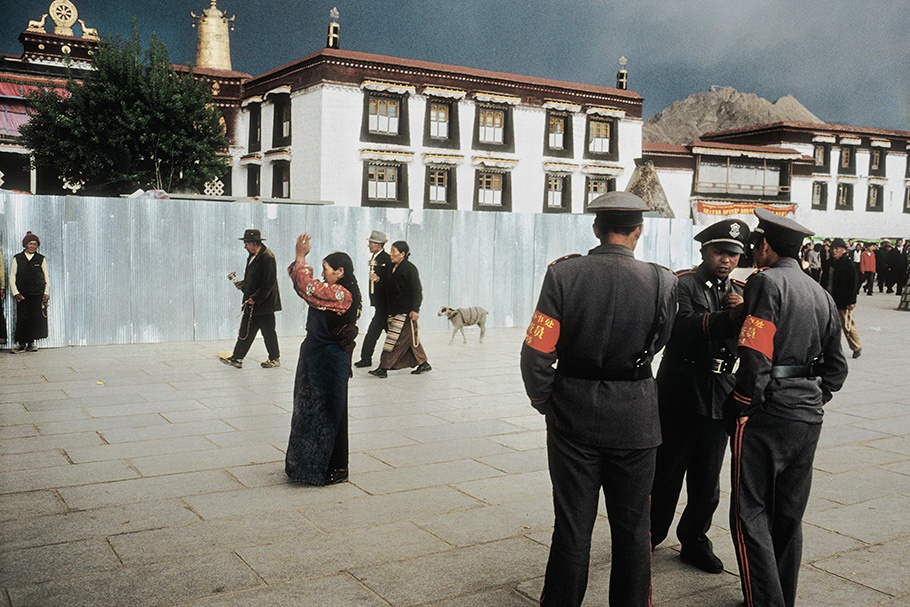

Jokhand Square, Lhasa, May 2002.

Pilgrims in the holy center of Lhasa are under strict police surveillance. This square has been the site of numerous demonstrations against the Chinese occupation.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-002

Lhasa, May 2002.

Many Chinese fashion stores have opened in east Lhasa, the traditional Tibetan section of town.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-003

Lhasa, May 2002.

A Tibetan pilgrim, carrying a prayer wheel, walks along Barkhor Street, a devotional route in the center of Lhasa.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-004

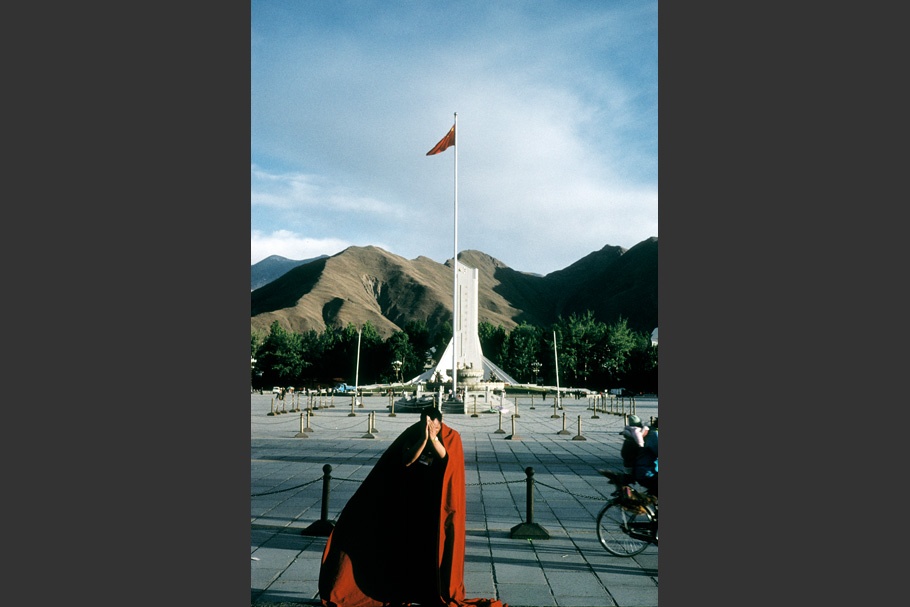

Lhasa, May 2002.

A Tibetan monk prays in front of the Potala Palace, the former residence of the Dalai Lama. Behind him the Chinese have built a monument to the glory of the liberation of Tibet.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-005

Barkhor district, Lhasa, May 2002.

Open-air pool halls, whose young clientele have forgone traditional clothes in favor of Western fashion, are common in the Barkhor district.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-006

Lhasa, May 2002.

Pilgrims.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-007

Lhasa, May 2002.

A billboard on the western outskirts of Lhasa shows Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, and Jiang Zemin smiling in front of the Potala Palace.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-008

Lhasa, May 2002.

A group of policemen take a break for lunch in the center of Lhasa. Most of the uniformed police in the city center are Tibetans.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-009

Lhasa, May 2002.

Young Tibetan boys dressed up as gangsters walk along one of Lhasa's main avenues.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-010

Lhasa, May 2002.

A young Tibetan in front of the Potala Palace. Behind him are the banks and shopping malls of the new Lhasa.

20051201-chatelin-mw11-collection-011

Lhasa, May 2002.

A Tibetan monk walks around the Lingkhor, the devotional route that encompasses the holy sites of Lhasa. This area, in western Lhasa, is now predominantly Chinese.

After graduating with a BFA in photography from the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, Julien Chatelin returned to his native France in 1992 and began covering issues surrounding the post-communist transition in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. His work was particularly focused on turmoil that broke out in the newly independent states in the Caucasus, documenting the conflicts in Abkhazia, Chechnya, and producing several features on Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

In 1994 Chatelin joined REA press agency in Paris, where he was assigned to cover social issues in France, such as the emergence of crack cocaine in Paris, unemployment, homelessness, emigration, and the problems of suburban ghetto towns.

Chatelin later joined Icône, a newly created agency, and began working on a series of stories on nations struggling for statehood. This took him to the Caucasus, Kosovo, Western Sahara, Kurdistan, and Tibet.

In 2000 he co-founded the documentary photography magazine de l’air, which has received accolades in the photography and design world. Chatelin’s work has been featured in numerous publications, including Paris Match, Figaro Magazine, Marie Claire, VSD, Le Monde 2. He is currently working on a project on the polarization of Israeli youth.

Julien Chatelin

A three-day drive separates Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet, from the Nepali border. Three days during which one is confronted by staggering landscapes: 17,000-foot high passes, mountain lakes, Mount Everest. In the villages and Buddhist temples, it seems nothing has changed since China invaded Tibet in 1950. The nomads, shepherds, and peasants appear untouched by both globalization and the Chinese occupation.

Then comes the asphalt, Land Cruisers, checkpoints, men in business suits, women in platform shoes, the endless avenues of steel and glass and neon—Lhasa. The exotic images in the guidebook look nothing like this Tibet. Sitting high up on a hill overlooking the city is the Potala Palace, the official residence of the exiled Dalaï Lama. But in the deserted square below a Chinese flag flies over a monument dedicated to liberation of Tibet by Chinese forces. Surrounding the square are gleaming new department stores, military barracks, and cell phone shops.

This city of 300,000 is 10 times larger than it was 50 years ago. Today, over half its residents are Chinese. Signs of Tibetan culture in Lhasa are inconspicuous—a traditional prayer flag strung across a rooftop—or else exploited for tourism value. In the ancient Barkhor quarter, along the way to the holy Jokhang Temple, pilgrims walk past souvenir shops, sharing the streets with tourists and a handful of Chinese policemen.

There is hardly any talk of politics here. Breaking the silence is treated with fear and suspicion by most Tibetans, who have adjusted to living under Chinese rule. A billboard on the outskirts of Lhasa shows Deng Xiaoping, Mao Zedong, and Jiang Zemin in front of Potala palace, wearing beatific smiles—a cynical reminder that, with China’s dominance, the people of Tibet have new leaders that they must worship and obey.

—Julien Chatelin, December 2005