20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-001

Tubmanberg, June 2003.

A fighter from the rebel faction Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) cleans his weapon before the final assault on the Liberian capital Monrovia.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-002

Monrovia, June 2003.

LURD fighters indiscriminately shell the capital Monrovia. Over a thousand people died in the ensuing bombardment. These mortar rounds were manufactured in the USA and supplied via the Guinean military.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-003

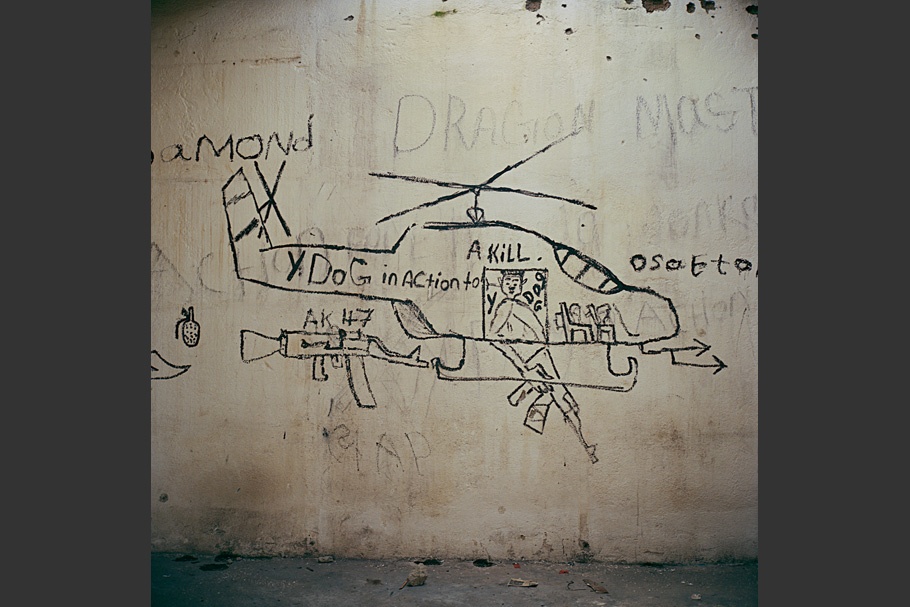

General Samuel Kollie Town, April 2004.

Graffiti left by fighters who had occupied the town some months earlier.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-004

Monrovia, June 2003.

Civilians flee as LURD fighters begin to shoot at looters.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-005

Monrovia, June 2003.

Two lovers exchange brief words before heading off to the frontline during the fighting in Monrovia.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-006

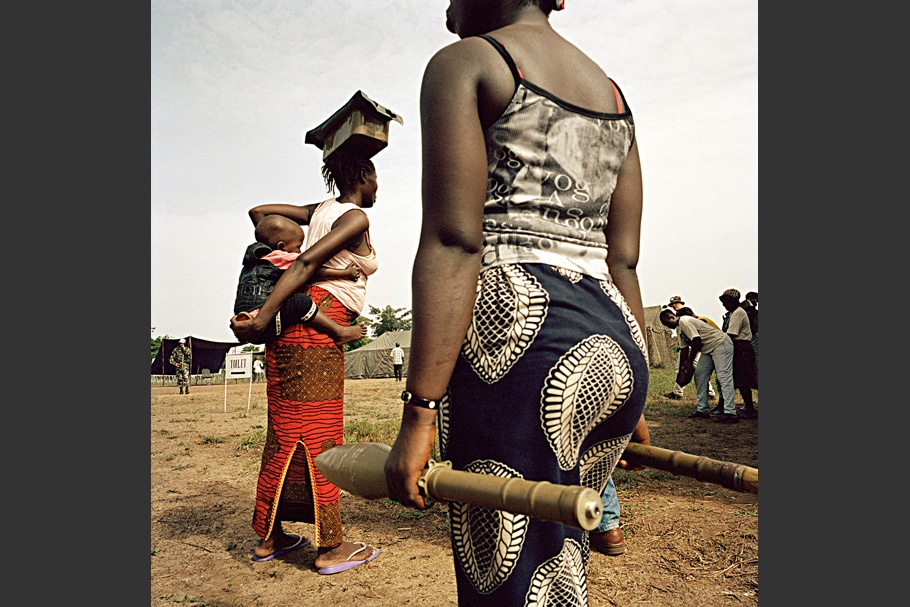

Tubmanberg, April 2004.

Women affiliated to the LURD rebel group bring ammunition and rockets to a United Nations sponsored demobilization camp.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-007

Monrovia, October 2003.

A thief caught by a mob shouts for help from a passing UN patrol. The presence of the UN meant that the individual was not beaten or burnt to death.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-008

Monrovia, September 2004.

Sunrise over downtown Monrovia.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-009

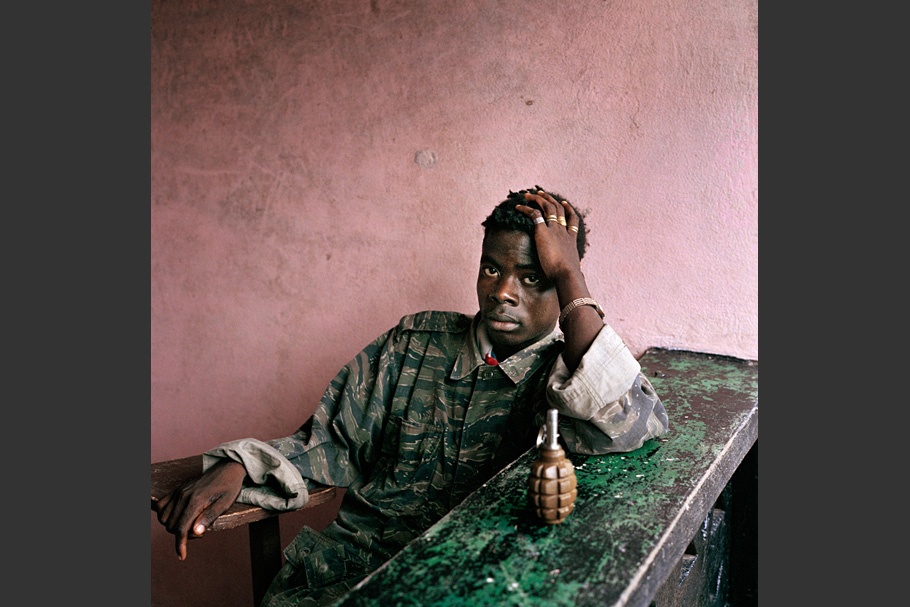

Tubmanberg, May 2003.

Young LURD rebel with grenade. He was later shot in the head during the assault on Monrovia.

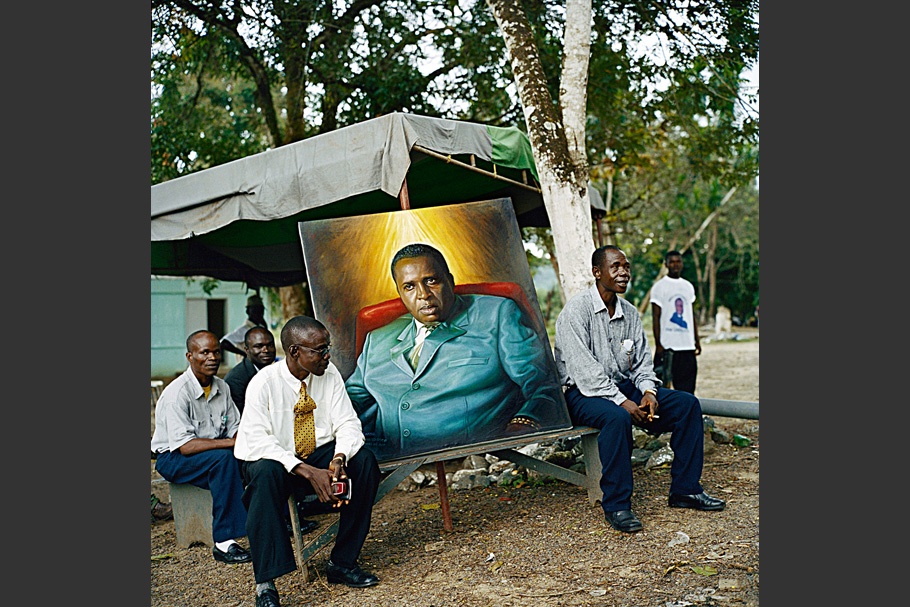

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-010

Tubmanberg, October 2003.

A group brings a portrait of LURD rebel warlord, Sekou Damate Conneh, to his headquarters in Bomi County after an end to the war had been negotiated. Incidentally, the painting was copied from a portrait I made of the warlord in May 2003, which the artists found printed in a magazine.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-011

Monrovia, July 2004.

Liberian National Police patrol an area of Bushrod Island during a murder hunt for a man accused of stabbing to death a U.S. army contractor in his hotel room.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-012

Monrovia, July 2004.

Weaponry that has been handed in as part of the disarmament program is broken down and destroyed.

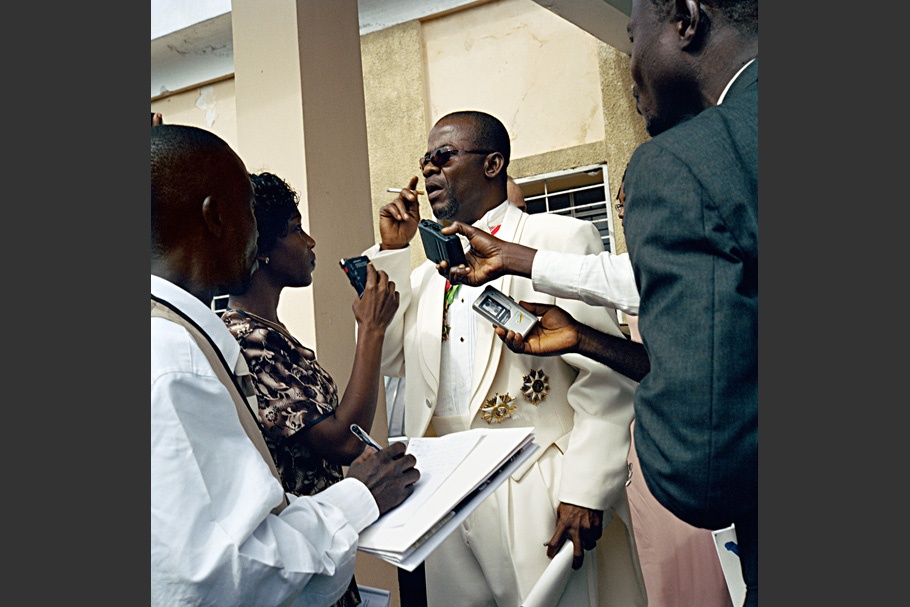

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-013

Monrovia, October 2003.

Cyril Allen, chairman of Charles Taylor's old political party the National Patriotic Party, speaks to journalists outside the National Pavilion following the inauguration of the new government.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-014

Monrovia, October 2003.

Members of the United Nations Mission in Liberia depart from the inauguration ceremony of Gyude Bryant as president of the National Transitional Government of Liberia.

20051201-hetherington-mw11-collection-015

Monrovia, April 2004.

A bridesmaid waits for a couple during a wedding photo shoot at the Centennial Hall.

Tim Hetherington was born in Liverpool, United Kingdom, in 1970. He studied English and Classics at Oxford University and worked as a writer and editor of children’s books, before taking up photography in 1996.

Hetherington works to create diverse forms of photographic communication from digital projections at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London to fly-poster exhibitions in Lagos, Nigeria. Recent projects include Healing Sport, Blind Link Project, and Liberia. He is a recipient of numerous awards including a research grant from the Hasselblad Foundation, two prizes from World Press Photo, and a fellowship from the National Endowment for Science, Technology, and the Arts.

Since 2003, he has worked as a cameraman and filmmaker, helping to create six films for television. He earned an award from the International Documentary Association for his work on Liberia: An Uncivil War, which was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam.

Tim Hetherington

“When two elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers.” —African proverb

In the summer of 2003, a secretive rebel group calling itself Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) launched its final attacks on Monrovia, the nation’s capital. The rebel army had fought four years in the interior of the country, and now it neared the seat of power with the aim of removing President Charles Taylor from office. Under his tenure as warlord and then president, Liberia had reached its nadir as an isolated, failed state. Fighters from former factions, disgruntled individuals, and those looking for a way to survive made up the LURD. Though some professed the rhetoric of liberation, they all hoped that the removal of Taylor would lead to economic enrichment.

Most of the fighters had grown up knowing only war. The cycle of violence that has gripped Liberia since the 1980s is a product of a confused and incomplete relationship with democracy that dates back to the founding of the country over a century and a half ago. When Samuel Doe came to power after an opportunistic coup in 1980, he ordered 13 ministers from the previous administration to be executed without trial. They were shot on a beach in downtown Monrovia in front of a gathered crowd. Witnesses said that the soldiers assigned to the execution squad were so drunk that it took a long time to kill all the ministers. The spectacle demonstrated that there would be no rule of law in the country. By the mid-nineties, the violence had spiraled out of control and the country had become synonymous with brutality and injustice. Along with the fighting, looting and stealing became the prime economic activity of anyone in power. Members of the ruling elite exploited the country’s natural resources and neglected government institutions to further their personal wealth.

The corruption and violence touched all Liberians. My friend Mamaya was raped as a young woman by government militia troops. She rose in the ranks of a rebel group to become a feared frontline commander, known to shoot her own troops if she caught them raping. My driver Issa was once a bodyguard for the warlord Alhaji Khromah. Issa does not like guns, but he was big enough to become a human shield for Khromah, standing behind him in case someone tried to shoot him in the back. Zum, a local journalist and friend, does not trust his neighbors anymore, not after he got trapped by fighting in the center of town and returned home to find they had looted it.

They say Monrovia is a small village of personal relationships. Everyone knows each other, and if you search hard enough, you will find everyone is connected—through family or business relationships. This network is focused on the pursuit of power and money, and violence is used as a tool. But one cannot discern these details watching the news, so the war seems confusing to those on the outside.

There are two Liberias, two worlds that are far apart but that sometimes intersect. One is the world of Liberians and reflects their individual struggle with history and circumstance. The other is the world of the international community, led by events and the preoccupations and agendas of organizations like the United Nations and international NGOs. The international media often portray Liberia as a place of abstract violence and faceless individuals. As the only photographer to live with the rebels during the war, I was granted a unique perspective. My evolving work is an attempt to describe how the events of war intersect with personal lives. I want my images to evoke the contrast between inside and outside, the personal and the historical, and the individual and the event.

—Tim Hetherington, December 2005