20050316-berman-mw10-collection-001

Spc. Adam Zaremba

20 years old

1st Armored Division

Wounded July 16, 2003 in Baghdad when a mine exploded.

Lost his left leg and suffered shrapnel wounds to his head, right leg, arms, and hands.

Photographed April 9, 2004 at Fort Riley, Kansas.

"I joined in high school. The recruiter called the house. He was actually looking for my brother and happened to get me. I think it was because I didn’t want to do homework and then, I don’t know, you get to wear a cool uniform. It just went on from there. I still don’t even understand a lot about the Army."

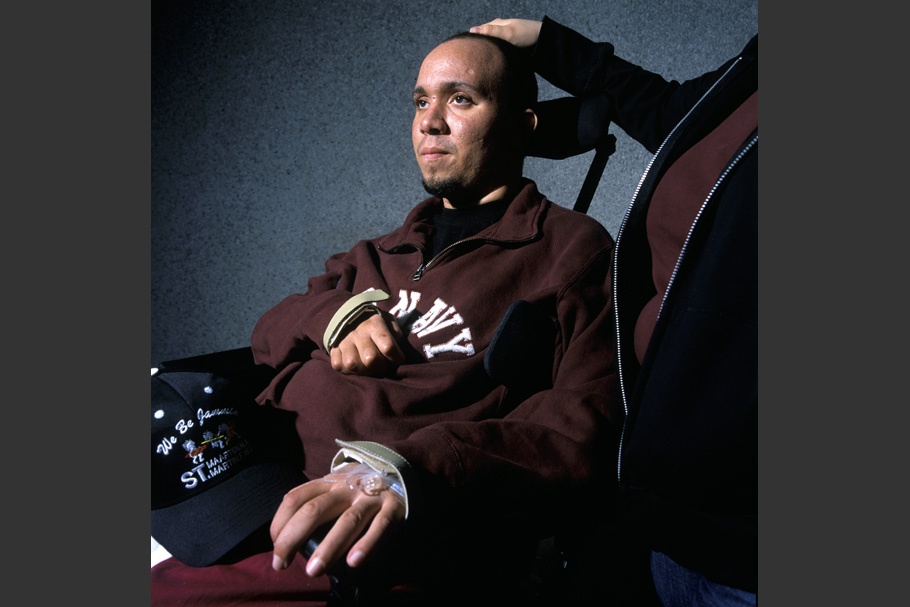

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-002

Spc. Robert Acosta

20 years old

1st Armored Division

Wounded July 13, 2003 in Baghdad when a grenade was thrown at his Humvee.

Lost his right hand and the use of his left leg.

Photographed April 13, 2004 at home in Santa Ana, California.

"I mean like all the reasons we went to war, it just seems like they're not legit enough for people to lose their lives for, and for me to lose my hand and use of my leg, and for my buddies to lose their limbs."

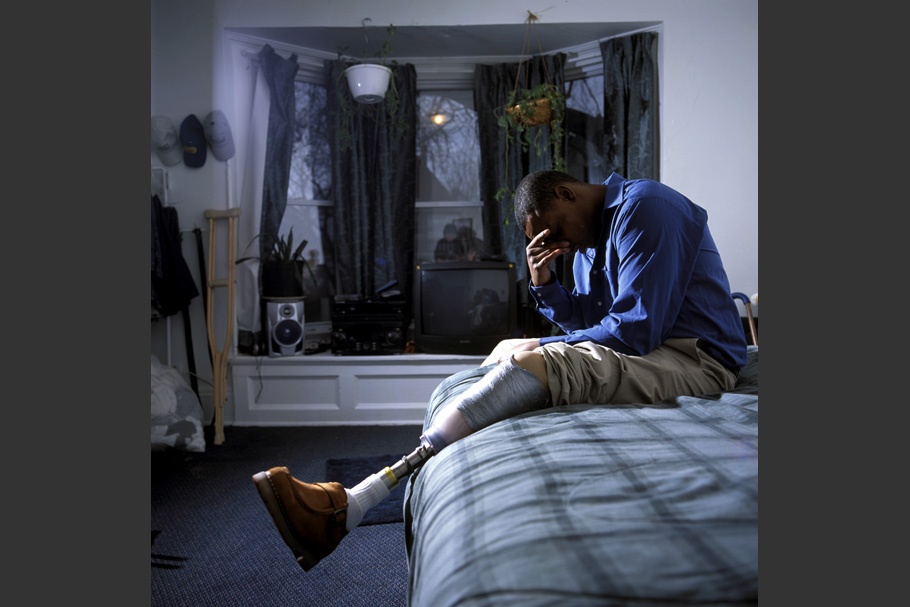

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-003

Pfc. Alan Jermaine Lewis

23 years old

3rd Infantry Division

Wounded July 16, 2003 in Baghdad when his Humvee hit a land mine.

Lost both his legs, suffered burns on his face, and broke his arm in six places.

Photographed November 23, 2003 at home in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

"I always thought about death, way before I joined the military, growing up in Chicago and living out here in this world. I had a friend when I was six, his name was Charles. He got killed. He was shot in the head. My oldest sister was killed by a stray bullet. And my father was killed when I was seven. He was being robbed. So death has always been around."

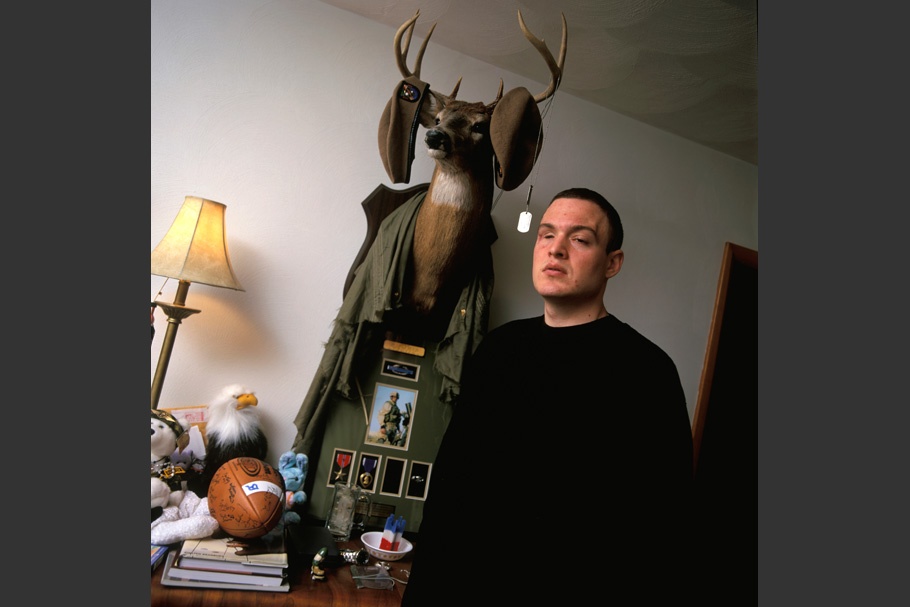

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-004

Sgt. Jeremy Feldbusch

24 years old

3rd Battalion Ranger

Wounded April 3, 2003 in an artillery attack near the Haditha Dam.

Blinded and suffered brain damage.

Photographed October 18, 2003 at home in Blairsville, Pennsylvania.

"I graduated from the University of Pittsburgh. I had a great time there. I was a biology major. At one point in my life, I wanted to be a doctor. I knew about the Middle East as much as I needed to. It didn’t make a difference. I wasn't fighting a political war with them. That was already taken care of. That’s about it. I don’t have any regrets. I had some fun over there. I don’t want to talk about the military anymore."

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-005

Cpl. Tyson Johnson III

22 years old

205th Military Intelligence Brigade

Wounded September 20, 2003 in a mortar attack on the Abu Ghraib prison.

Suffered massive internal injuries.

Photographed May 6, 2004 at his home in Prichard, Alabama.

When he returned home, Johnson was denied treatment at the local veterans hospital and told that he had to repay his signing bonus of nearly $3,000 because he did not fulfill his military contract.

"We went to the concentration camp there, the prison. Most of my friends were losing it out there. They would do anything to get out of there, anything. One of my guys, he used to tell me, 'My wife just had my son. I can’t wait to get home and see him.' And, you know, he died out there. He sure did, and I have to think about that everyday."

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-006

Lt. Jordan Johnson

23 years old

1st Armored Division

Injured July 20, 2003 near Baghdad International Airport when her Humvee crashed and turned over.

Broke her legs and her tail bone, and suffered a coma.

Photographed March 26, 2004 at home near the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas.

After months of rehabilitation, Johnson regained limited use of her legs. Despite her strong objections and a diagnosis of chronic post-traumatic stress syndrome, Johnson was ordered back to her unit in July 2004.

"All I really want out of this is to be able to walk again, to run again. I went from a star athlete to not being able to do six repetitions. It’s a very slow process, but I’m dealing with it. I don’t need a medal or any kind of badge or award that says who I am because I know who I am. I’m not a hero. I’m a survivor."

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-007

Sgt. John Quincy Adams

37 years old

Reservist with the Florida National Guard, 124th

Wounded August 29, 2003 in Ramadi when a remote-controlled bomb exploded under his Humvee.

Suffered brain damage from shrapnel wounds to his head.

Photographed December 18, 2003 at home with his wife, Summer, in Miramar, Florida.

"I was doing landscaping work and lawn services in North Miami with my father-in-law. I loved it. Now I like being with the kids and my wife. I try to be with them always. I take them both with me and my wife to the veterans hospital."

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-008

Spc. Luis Calderon

22 years old

4th Infantry Division

Wounded May 5, 2003 in Tikrit when a concrete wall with the image of Saddam Hussein that he was ordered to destroy collapsed on him.

Severed spinal cord left him a quadriplegic.

Photographed December 17, 2003 at the Miami Veterans Hospital.

"From my neckline down, I cannot feel anything. I got an Army Commendation Medal. I didn’t get a Purple Heart. I feel like I deserve one. It would make me more confident that I really did something."

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-009

Spc. Sam Ross

21 years old

82nd Airborne

Wounded May 18, 2003 in Baghdad when a bomb exploded during a munitions disposal operation.

Blinded and lost his leg.

Photographed October 19, 2003 in the woods near his trailer in Dunbar, Pennsylvania.

“I lost my leg just below the knee, lost my eyesight. I have shrapnel in pretty much every part of my body. Got my finger blown off. It don’t work right. I had a hole blown through my right leg. You know, not really anything major. I get headaches. And my left ear, it don’t work either. I don’t have any regrets. It was the best experience of my life.”

20050316-berman-mw10-collection-010

Pfc. Randall Clunen

19 years old

101st Airborne

Wounded December 8, 2003 in a suicide bomber attack.

Suffered shrapnel wounds to his face and jaw.

Photographed February 14, 2004 at his home in Salem, Ohio.

“I liked it: the excitement, the adrenaline, never knowing what’s going to happen. I mean, you could walk in the house and it would blow up, or you could go in and get fired at. Now, there’s nothing. You just watch the news or you watch the war movies on TV. I want to find Hamburger Hill—that’s a good one about the 101st. My dad, we’d sit here and watch them, a lot of John Wayne movies, too.”

Nina Berman was born in New York City. She received a BA from the University of Chicago, an MA from Columbia University’s School of Journalism, and has been photographing the political and cultural landscape in the United States for nearly 15 years. Berman’s photographs have been exhibited in museums and widely published in magazines including Time, Mother Jones, Harper’s, GEO, and National Geographic. She currently resides in New York City where she teaches at the International Center of Photography.

Her first book, Purple Hearts—Back from Iraq, was published by Trolley in 2004, followed by a second printing six weeks later; a Japanese version is due out in 2005. The book has received widespread press attention including coverage on ABC, CBS, NPR, MSNBC, dozens of internet sites, and features in Mother Jones and the Los Angeles Times. Excerpts from the book have been published in magazines and newspapers in eleven European countries.

Nina Berman

The image of a wounded American soldier is one piece of evidence that the American public can examine to begin separating propaganda—that war is quick and bloodless—from truth.

Since October 2003, I have been making pictures and conducting interviews with Americans wounded in the war with Iraq. I stay away from the homecoming parades, the VFW initiation events, the yellow ribbons, and appearances with politicians. I seek out the wounded at their homes after they have been discharged from the military hospitals. I want to visit each soldier alone as he or she considers the experience of war and life ahead. I ask questions about their lives at home, the recruitment process, their injuries, what they liked about the military, and their experiences in Iraq. I ask the soldiers for their definitions of freedom and democracy—a question that often leaves them puzzled.

Together, the words and photographs create a complex, sometimes contradictory portrait of American youth, depicting their values and their dreams, the lack of opportunity many face after high school, the culture of violence or drugs that many tried to escape by enlisting, and the myths of warfare that influenced their decisions to join.

The first soldier I photographed was completely blind. His world is black from morning to night. Titanium plates hold his brain together. He has seizures and mood swings and needs frequent naps. This young man—tall and strong, a university graduate, and first in his class of 228 Rangers—trembled at the sound of the camera’s shutter.

Another soldier, blind and an amputee, described Iraq as “the best experience” of his life. He lives alone in a camper in one of the poorest communities in Pennsylvania. His father is in jail for homicide, his mother walked out on him as a child. Another soldier, crippled after a rocket-propelled grenade ripped through his legs in Falluja, said, “I thought going to war was jumping out of planes. I thought it would be fun.” He recalls watching Desert Storm on TV as a child and being mesmerized by the tracers and the nighttime bombings.

Many of the soldiers I photographed either supported the war in Iraq or said they had no political opinions and were just doing their job. But one soldier, Robert Acosta, was openly angry and critical of what he called the “Bush Administration’s lies.” Acosta, 20 years old, had his right hand blown off and his left leg mangled in a grenade attack. He agreed to be photographed because, he said, people needed to know what’s happening. He was alarmed by the ignorance in his neighborhood in Santa Ana, California, and was concerned about his younger brother being drafted. A high school dropout, he had never been interested in politics or world issues before joining the army. Now he is a vocal antiwar activist, speaking at colleges, doing interviews for radio shows, and participating in television ads. He wants the public to know the human cost of war.

These photographs are only a partial accounting of the true cost.

—Nina Berman, March 2005