20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-001

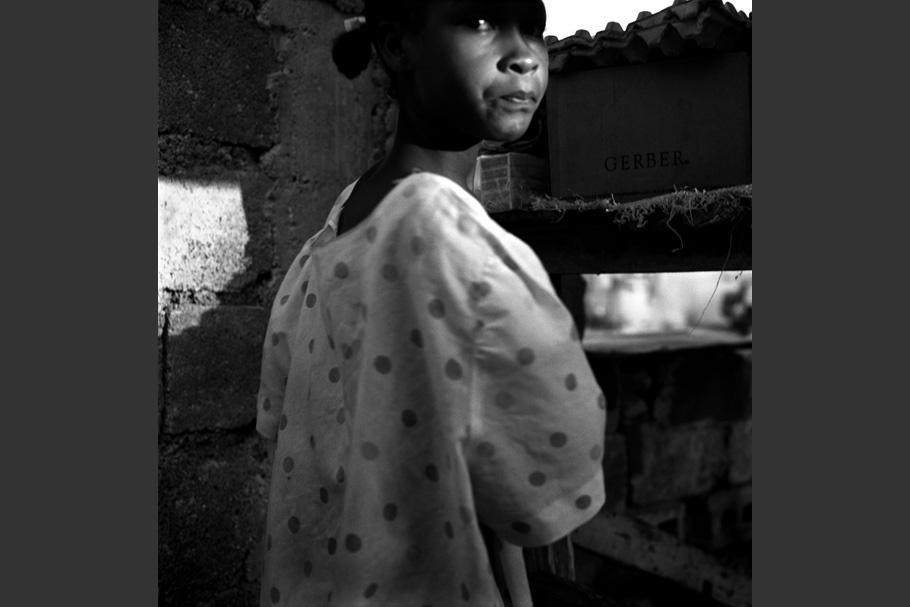

Up before dawn, Josiméne prepares the family’s small informal store.

20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-002

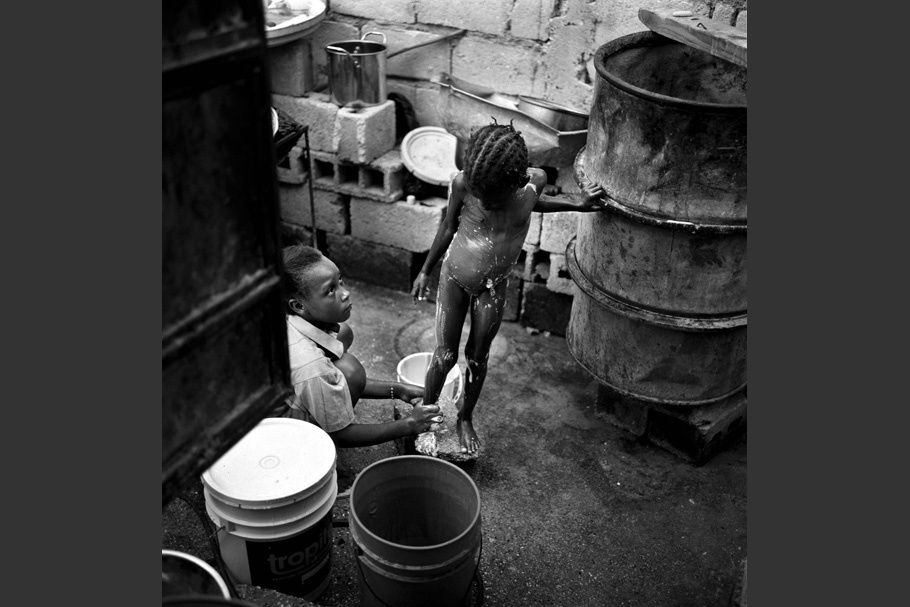

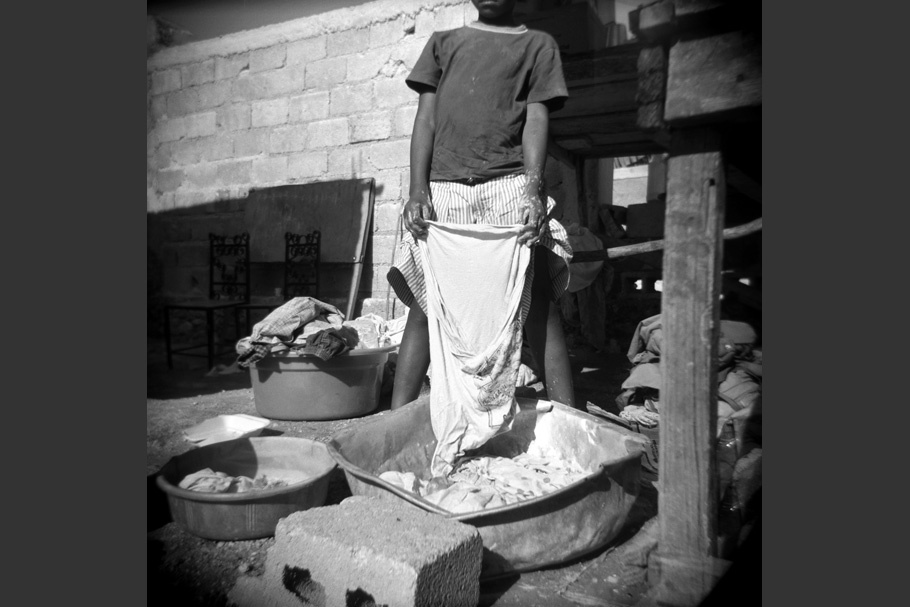

Josiméne bathes the family’s children, in between selling items at the store, washing dishes, and running errands.

20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-003

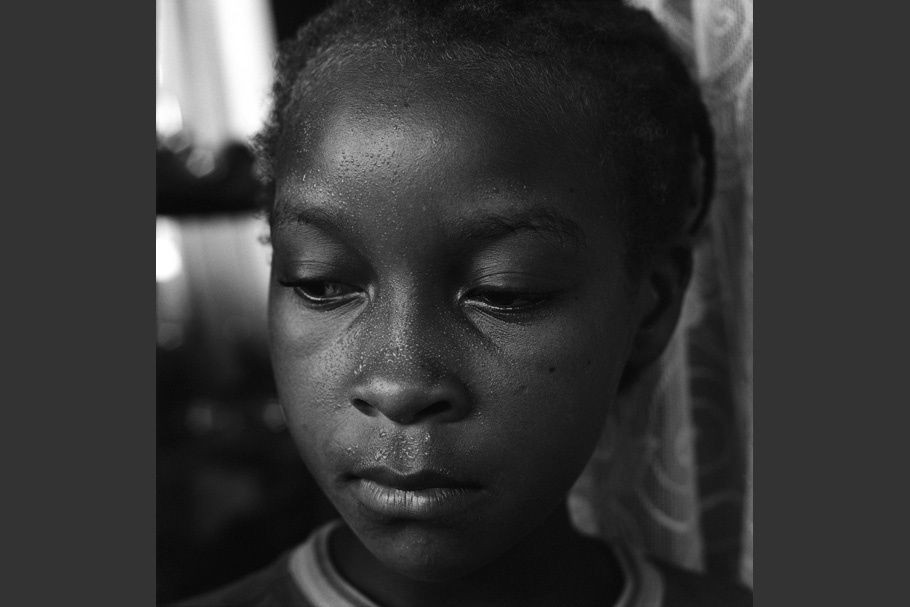

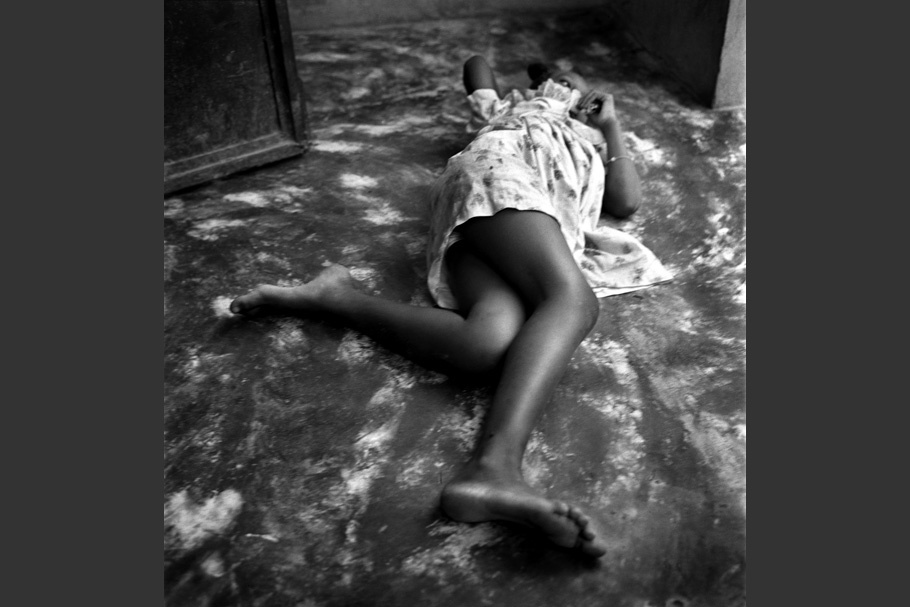

In the shade, Josiméne pauses between chores.

20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-004

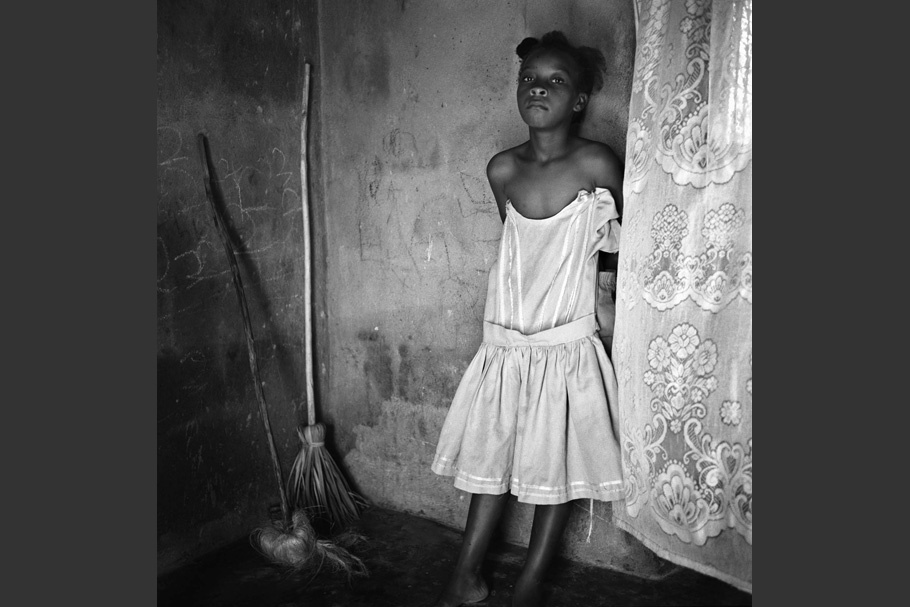

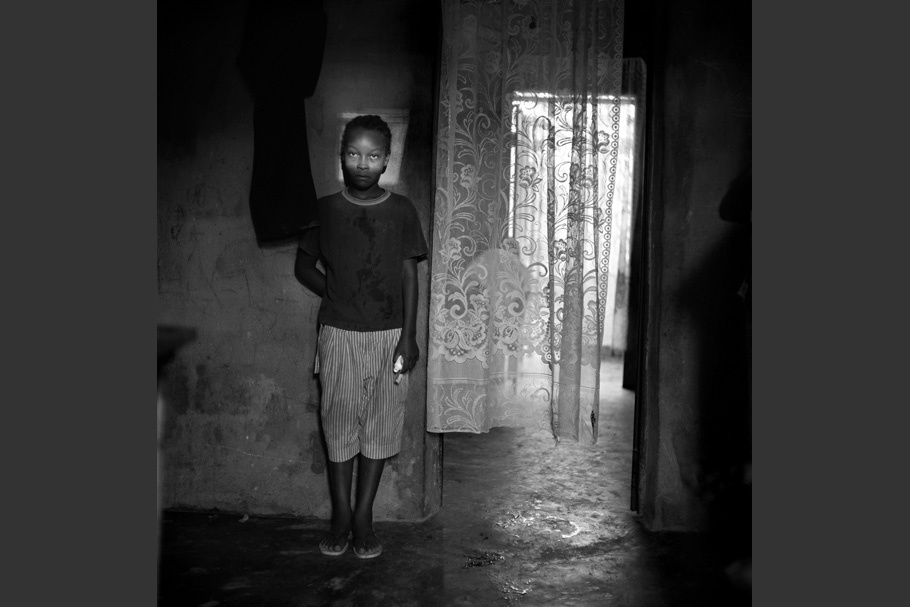

Josiméne possessions include this dress, two pairs of shorts, one skirt, a couple of shirts, a school uniform, and flip flops.

20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-005

Josiméne rises with the sun to work for the family of four.

20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-006

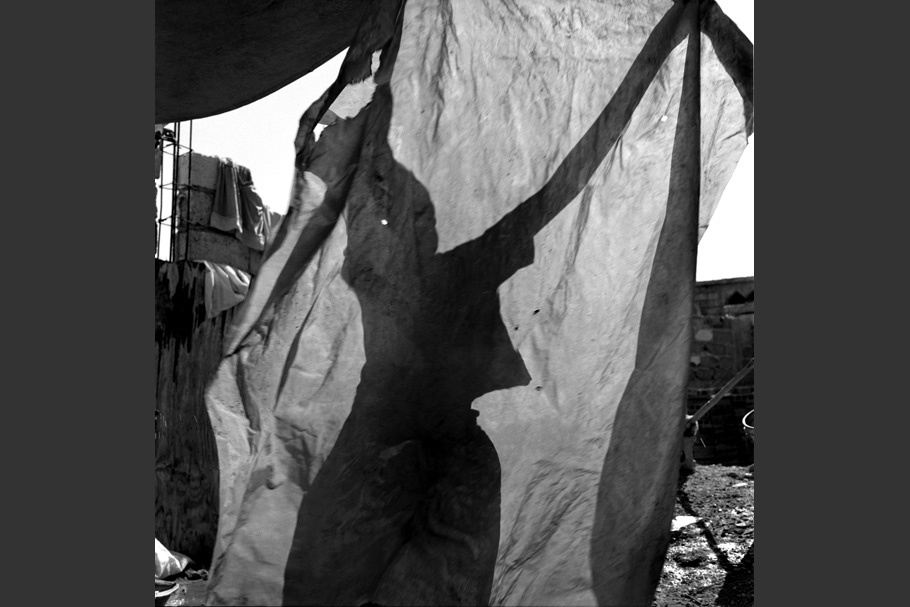

On laundry days, Josiméne hand washes clothes and spends the late afternoon hanging laundry.

20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-007

Shenandad, aged 5, points at Josiméne, while the girl’s mother fixes her hair.

20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-008

With piles of laundry washed, Josimène takes a moment to stretch her legs under the hot sun.

20050316-cohen-mw10-collection-009

Josimène spends most of the day in solitude.

Gigi Cohen, a New York-based photographer, began her career working for New York Newsday.

She is now a freelance photographer specializing in documentary photography and portraiture, focusing on a wide range of social issues—from incarceration, to AIDS, to children’s rights. Her photographs have appeared in the Sunday Times Magazine (London), the Independent on Sunday, L’Express, British Esquire, the New York Times Magazine, LIFE, and Der Spiegel, among others.

Cohen has worked in South Africa, Hong Kong, India, Poland, the Caribbean and throughout the United States. Her photographs have been exhibited internationally, in San Francisco, London, Leeuwarden, Madrid, Durban, Melbourne, Zurich, and New York City.

Self-funded, long-term projects include: death row inmate Philip Workman, in Tennessee; a group of street children living in a home in Soweto, South Africa; and an 89-year-old junk collector, in Brooklyn. Cohen’s emotional commitment to the people she photographs keeps her returning to these subjects.

Currently, Cohen has a grant from Kids with Cameras to work with child domestic workers in Haiti. The project is a continuation of her work for Child Labor and the Global Village: Photography for Social Change. In 2004, she was a fellow with the New York Foundation for the Arts.

Gigi Cohen

Josiméne, 10, works as a restavec, or live-in maid, in a two-room house outside of Port-au-Prince, Haiti's capital. When Josiméne was seven, her parents—small farmers in Haiti’s remote and mountainous heartland—asked a local woman to find a family that would take her as a servant. They believed that another family could give their daughter a better life and provide her with an education. Josiméne’s parents did not get paid for her placement with a family, nor do they get paid for the work she does for that family.

But Josiméne’s life is far from better. The reality for most of Haiti’s restavecs—a term that combines the Creole words for “to stay” and “with”—is one of harsh servitude. Josiméne’s day typically starts at 5:00 a.m. and ends after the family’s children, aged five and four, are asleep. Her day is full of household chores. She bathes the children, cleans the two-room house, washes dishes, scrubs laundry by hand, runs errands, and sells small items from the family’s informal store. At the end of the work day, after the family eats dinner, Josiméne is given the leftovers. At night she sleeps on the concrete floor, covered by thin bed sheets.

There is little time left for the education Josiméne’s parents had hoped she would receive. The Maurice Sixto Foyer, a nonprofit organization in a suburb of Port-au-Prince, offers free schooling for restavecs, but on many afternoons, Josiméne’s errands keep her too busy to attend.

Estimated numbers of child domestic workers around the world range into the hundreds of millions. Haiti, with a population of eight million, has an estimated 300,000 restavecs.

The line between basic housework and child labor, according to the International Labor Organization, is crossed when children are sold or trafficked, bonded to repay family debt, or exposed to safety or health hazards; work without pay or work excessive hours; suffer physical violence or sexual harassment; or are simply “very young.” The ILO says that the restavec practice is “tantamount to slavery.”

This story is part of the collaborative project, Child Labor and the Global Village: Photography for Social Change. For more information please go to: www.childlaborphotoproject.org.

—Gigi Cohen, March 2005