20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-001

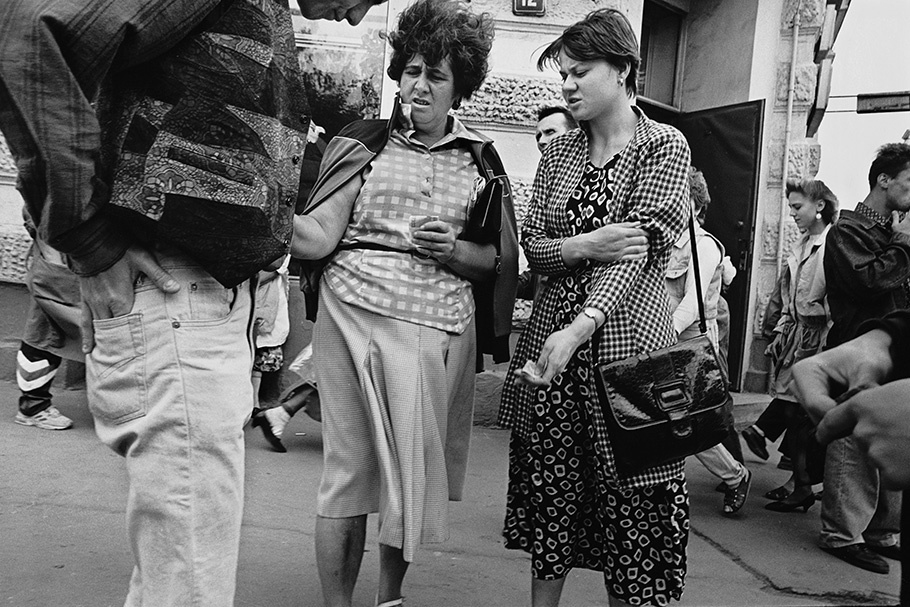

During the early 1990s, women outside "Pharmacy Store #1," the main pharmacy in Moscow, sold over-the-counter products that were frequently out of stock at the store, as well as an array of black-market pharmaceutical drugs. Here teenagers buy the tranquilizer ketamine, and a kit that includes an ephedrine-based cough syrup and other chemicals to make vint, a powerful homemade methamphetamine. Moscow, Russia, 1995.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-002

Street scene. Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, 1998.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-003

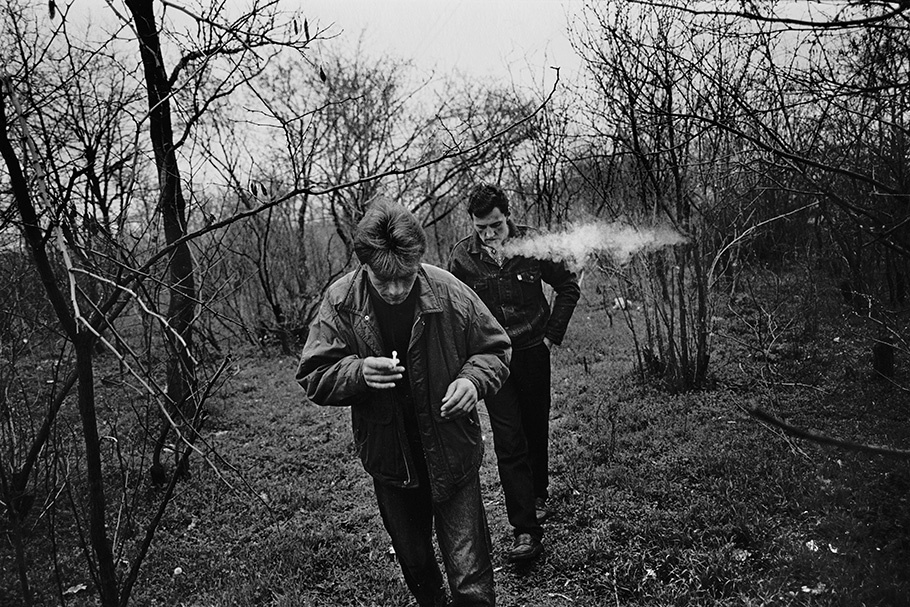

Two drug users search for a place to inject chornyi, which is made from opium straw. Odessa, Ukraine, 1997.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-004

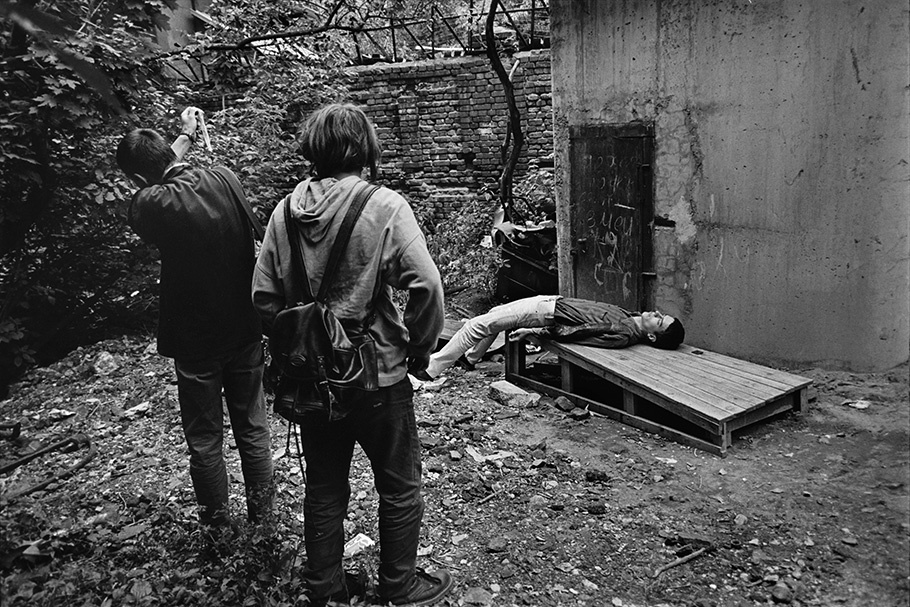

Syringes litter the rooftop of an apartment building. Odessa, Ukraine, 1997.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-005

University students shooting the tranquilizer ketamine. Moscow, Russia, 1995.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-006

Preparing to inject hanka, a solution made from opium tar. Omsk, Russia, 2001.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-007

Front-loading—dividing a full syringe into two doses using another syringe—can transmit disease if one syringe is contaminated. Here users bring their own syringes but frontload from a common source. Rostov na Donu, Russia, 1998.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-008

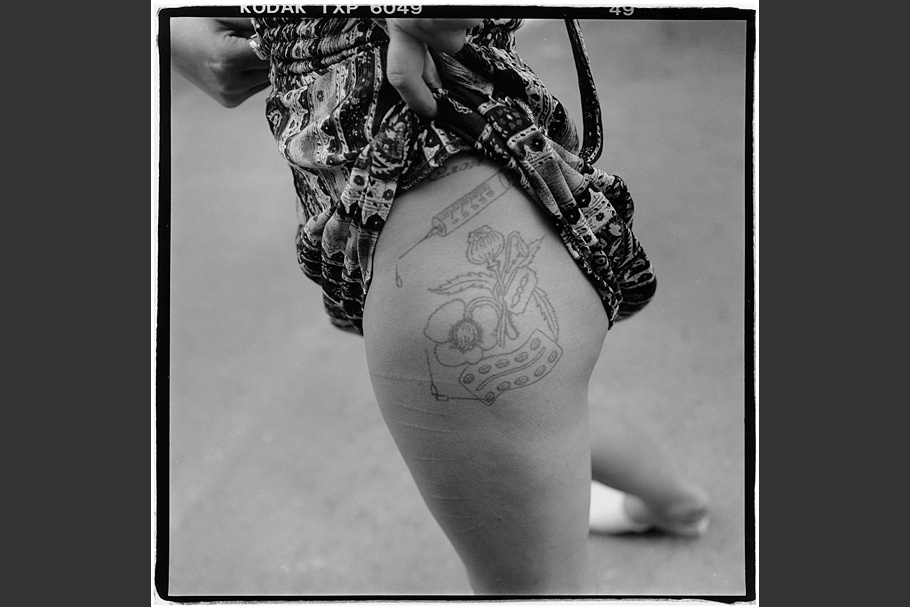

An inmate at the Krasnadar Prison Colony for Women shows off her tattoo. Krasnadar, Russia, 2001.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-009

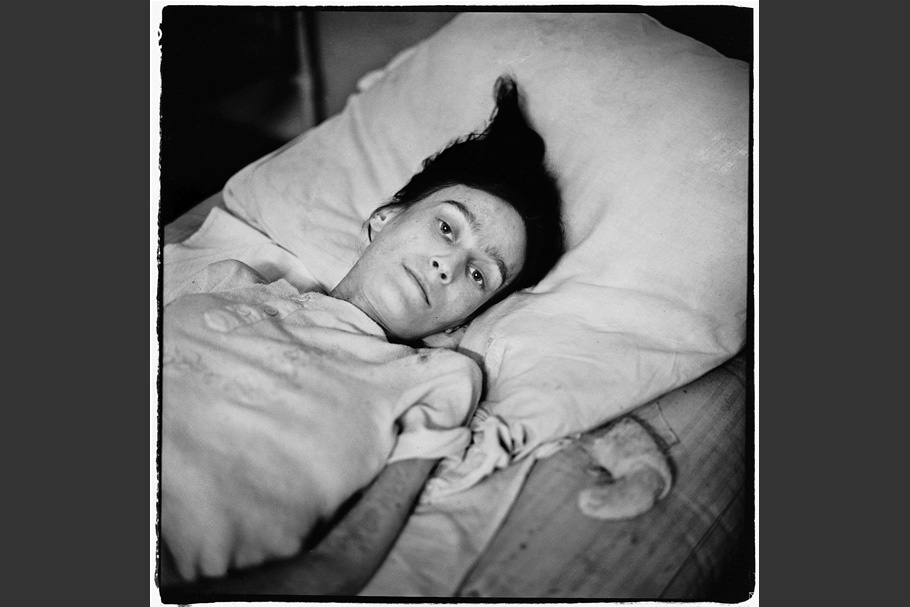

Diane, HIV ward. Odessa, Ukraine, 2000.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-010

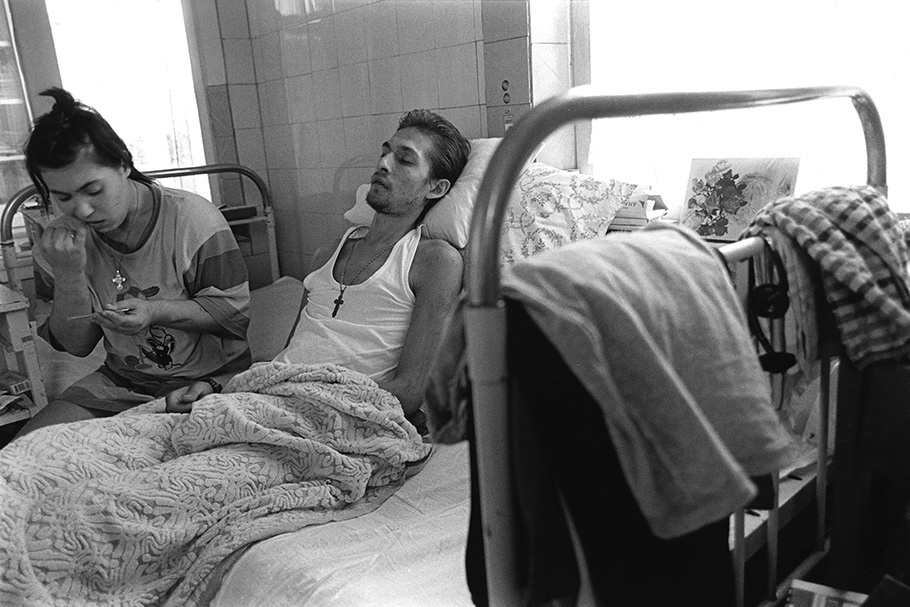

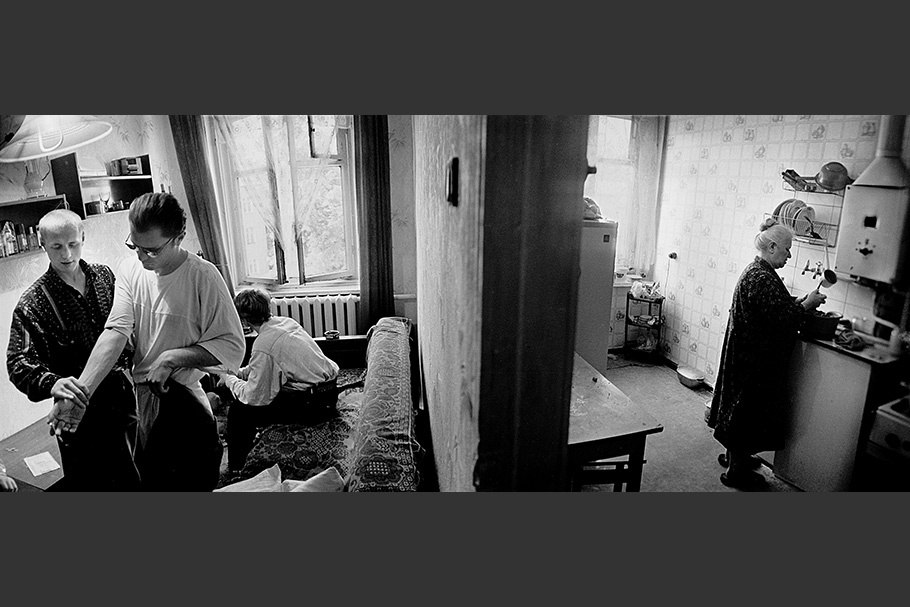

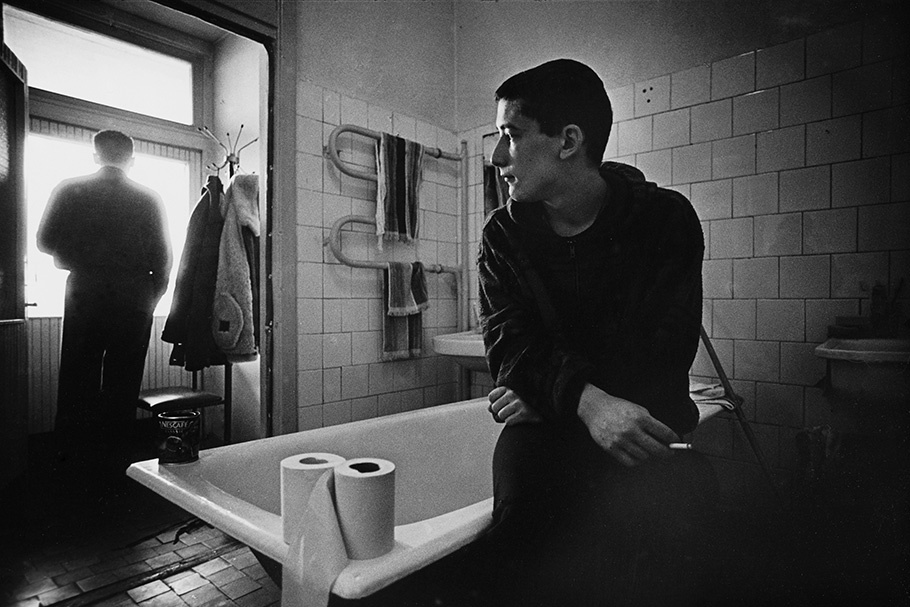

Sasha and his wife Natasha live in a private room in the AIDS ward of the Hospital for Infectious Diseases in Novorussiysk. They bring their own supplies, including sheets, toilet paper, and whatever medicine they can afford. Both are still addicted to opium and, since substitution therapy such as methadone maintenance is illegal, they also smuggle drugs into the hospital. Novorussiysk, Russia, 1998.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-011

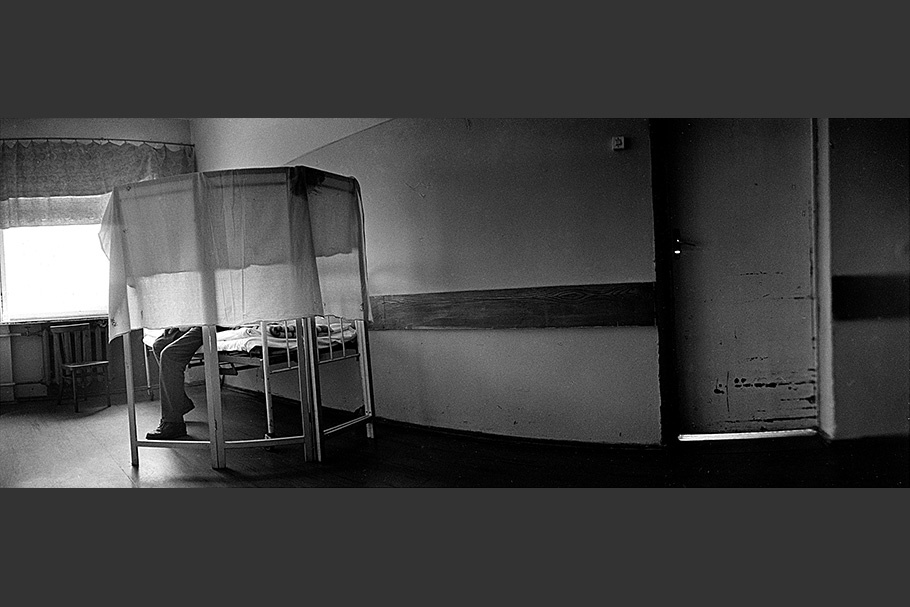

The HIV ward at the Rostov na Donu Hospital Prison Colony. Rostov na Donu, Russia, 1998.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-012

An HIV positive patient is segregated in a hallway at Kaliningrad General Hospital. Kaliningrad, Russia, 1998. Kaliningrad, Russia, 1998.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-013

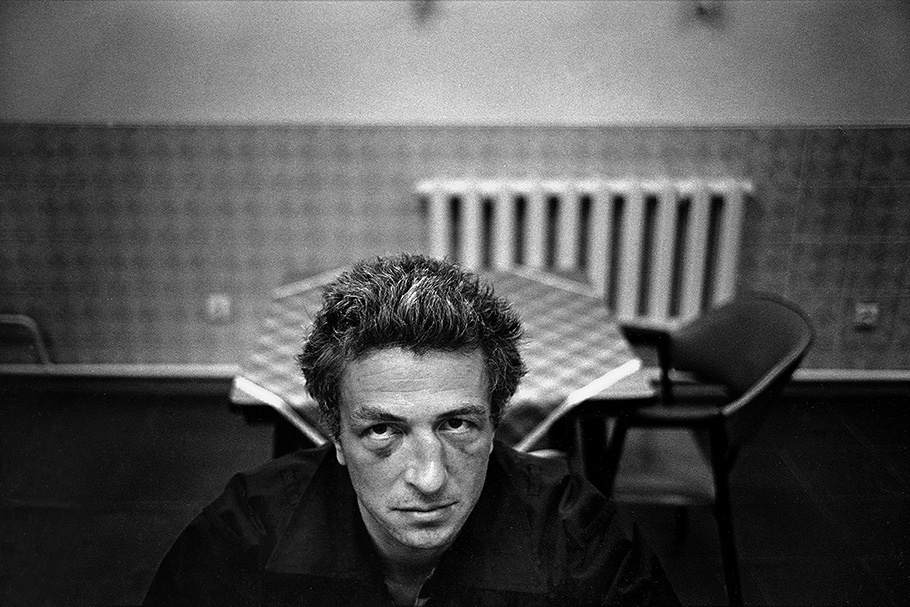

HIV-positive prisoner. Omsk, Russia, 2001.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-014

Without a search warrant, plain-clothes police officers demand to examine a drug user’s arms. Kaliningrad, Russia, 1998.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-015

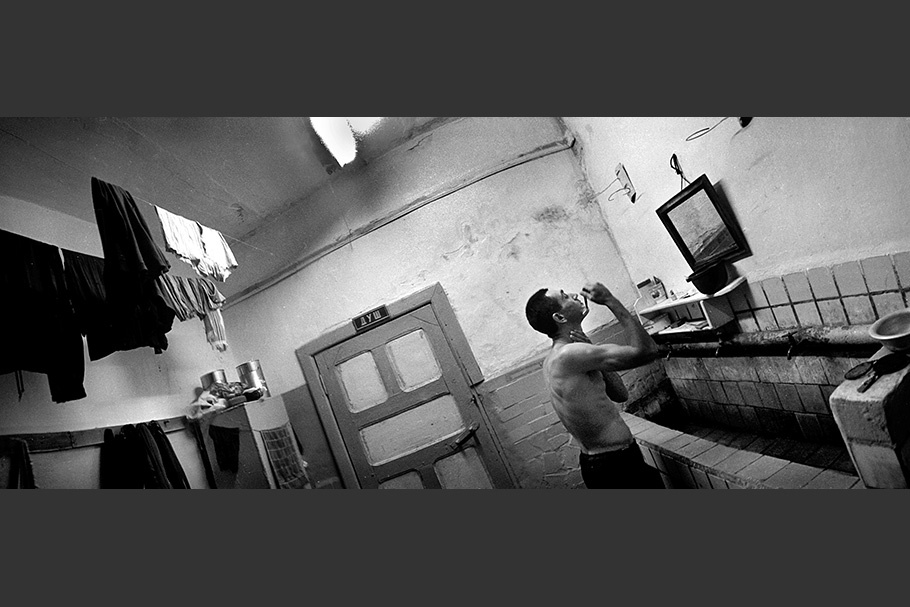

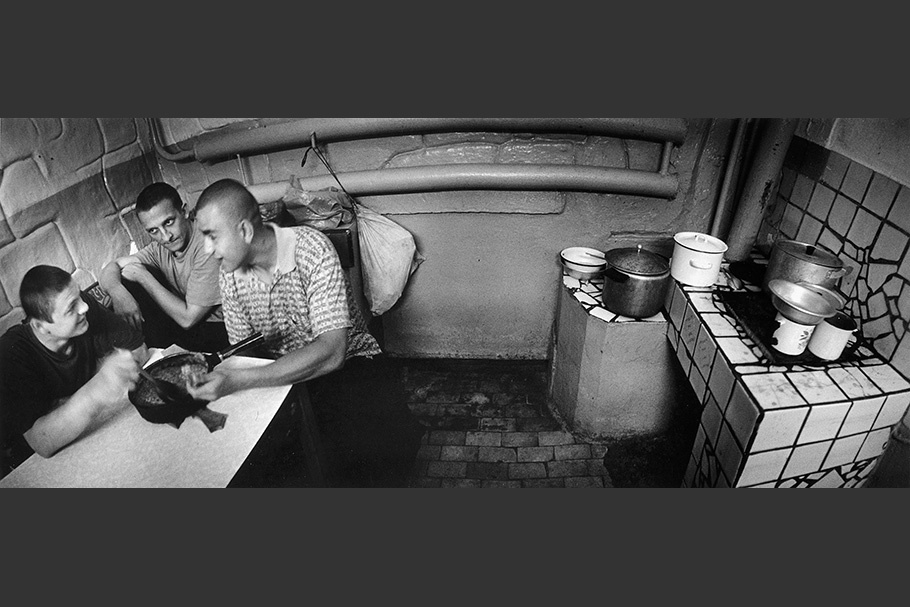

HIV-positive inmates are segregated from the rest of the population. They eat, sleep, wash and exercise in their own areas. Omsk, Russia, 2001.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-016

HIV patients in the Botkina Hospital for Infectious Diseases. St. Petersburg, Russia, 1997.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-017

Client of the Kaliningrad needle exchange who says he began injecting drugs in the late 80s. Kaliningrad, Russia, 2000.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-018

A multi-drug overdose patient is rushed to the hospital. The Volgograd Emergency Service registered 28 overdoses during November 2002. Volgograd, Russia, 2002.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-019

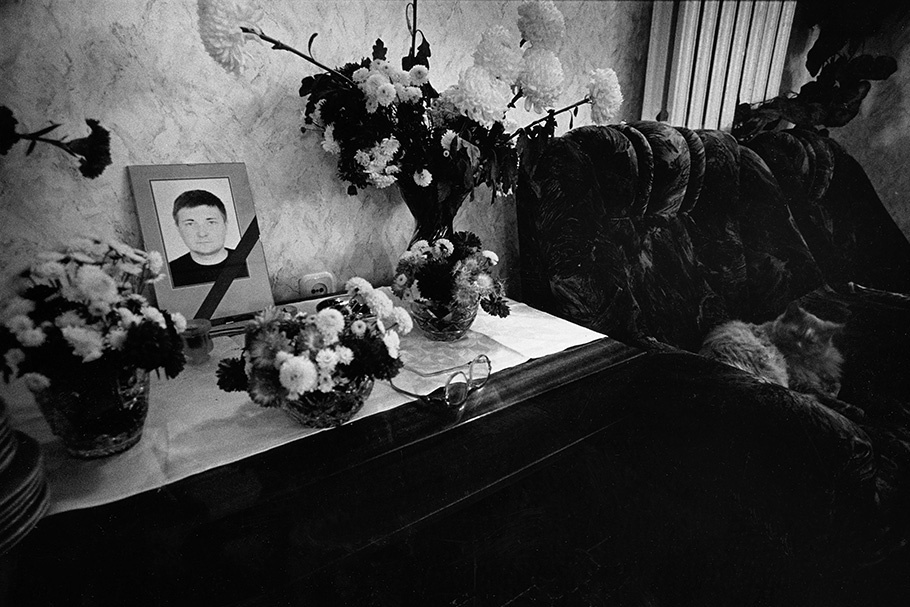

Funeral flowers surround the photograph of a young man who died of an overdose. Volgograd, Russia 2002.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-020

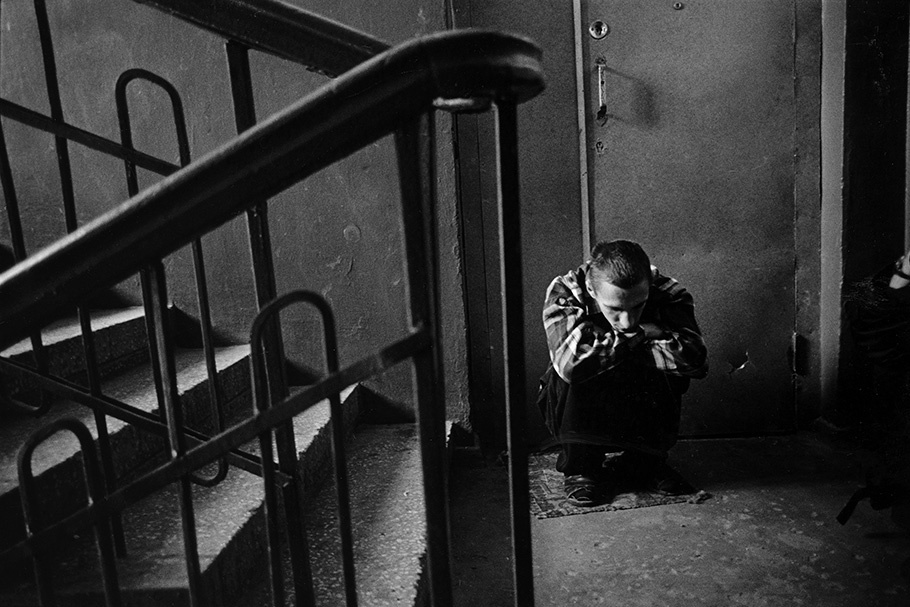

A dope-sick nogi (the word for middleman, which literally means “legs”) waits for customers outside the apartment he shares with his mother. He works for a cut of what is purchased. Volgograd, Russia, 2002.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-021

Odessa sex workers and madam. Odessa, Ukraine, 1997.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-022

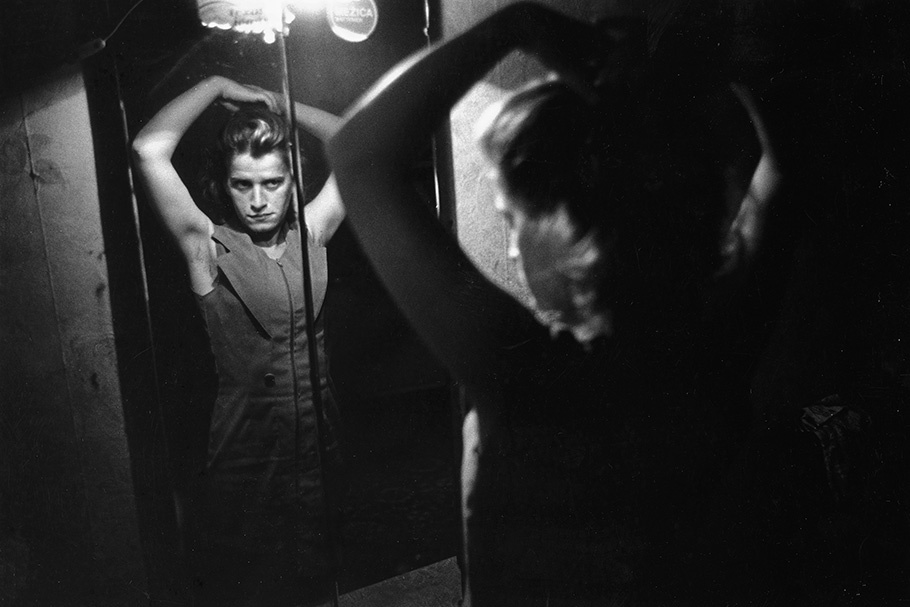

Trading sex for heroin. Moscow, Russia, 1998.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-023

A Volgograd sex worker works to feed her heroin habit. Volgograd, Russia, 2002.

20050316-ranard-mw10-collection-024

Natasha, who contracted HIV through needle-sharing, stopped using drugs and got a job working at a local needle exchange in Odessa. The antiviral drugs that could have prolonged her life were prohibitively expensive on her income of $30 a month, and being poor brought other problems that didn’t help her immune system. She drank tap water, as she was unable to afford safe, filtered bottled water, and subsisted on rye bread, cottage cheese, and potatoes. Fruits, vegetables, and sometimes red meat, were prepared only for special meals. On the days when she felt sick, she waited it out, hoping it would pass quickly. Sometimes she could find expired antibiotics on the black market, but her best defense, she told me, was faith.

According to the Médecins Sans Frontières team in Odessa, she was last seen in May 2002.

John Ranard is a social documentary photographer based in New York. He began photographing Russia’s emerging HIV epidemic in 1995 and is currently editing these photographs into a book that emphasizes a harm reduction approach to AIDS, which seeks humane and practical solutions to stem the spread of the disease.

AIDS Foundation East / West and Medecins Sans Frontieres jointly published a book of Ranard’s photographs, The Fire Within, as a policy statement on the need for harm reduction in Eastern Europe. His work for a 1997 New York Times story on the AIDS epidemic in the former Soviet Union won the first place Pictures of Year award for Issue Reporting Photo Story. The photographs are included in the anthology Pandemic: Facing AIDS (2003).

Ranard has exhibited at the Andrei Sakharov Museum in Moscow, the Center for Contemporary Art in Kiev, de Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, the Moscow Center for Prison Reform, and the Museum of World Culture in Gothenberg, Sweden, among other institutions.

Ranard’s portfolio “The Brutal Aesthetic” won the Kentucky Arts Grant—Al Smith Fellowship, and was published in Joyce Carol Oates’s On Boxing, which was named one of the Best Photography Books of 1987 by the International Center for Photography.

Ranard’s photographs are part of the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the University of Louisville Photographic Archives, and the Andrei Sakharov Museum.

John Ranard

These photographs examine the evolution of the HIV epidemic in Russia and Ukraine, where the vast majority of new infections are due to injecting drug use.

In the early 1990s, rumors circulated in Moscow and Kiev that Slavs had a peculiar immunity to HIV. In August 1995, after observing and photographing a group of typical Moscow university students, who injected a variety of drugs with little precaution or understanding of how disease is transmitted, I realized that the myth of immunity would not last long.

Russia’s younger generation experimented with vint, a powerful liquid methamphetamine made from cough syrup, or they boiled chonryi, opium poppy straw cooked with industrial solvents. Today, inexpensive but potent heroin is easily available everywhere, smuggled from Afghanistan and North Korea.

Russia and Ukraine quickly fell into a deadly downward spiral, with injecting drug use and HIV becoming inextricably linked. As the economy got progressively worse, many teenagers started using drugs as an antidote to the excruciating boredom of provincial urban life, few prospects to relocate, and no promising professional opportunities. Many young girls, some of them drug users, turned to sex work. This exchange of sex for drugs or money for food is fraught with risk of HIV infection and physical violence and has helped fuel the epidemic.

The governments of the two countries responded to the crisis with harsh law-and-order programs aimed at achieving a “drug free society.” But their policies have done little to curb drug use or the rate of HIV infection. Police harassed teenagers with track marks on their arms, and so drug users began to shoot drugs in their neck and underarms. And with drug users incarcerated for months in prisons with horrendously poor hygiene and little access to rudimentary health care, prisons became breeding grounds for the spread of both HIV and tuberculosis. Until recently, the possession of minute quantities of nonpharmaceutical drugs, including cannabis, was punishable with long prison sentences. In a move that may signal its readiness for drug policy reform, the Russian government in May 2004 changed this law so that people caught with very small amounts of drugs can no longer be sent to jail.

There is little money allocated for public health services or education. Antiviral treatment is virtually nonexistent in Russia and extremely limited in Ukraine. Methadone and other substitution therapies are illegal in Russia and are yet to be made available in Ukraine.

The deteriorating public health system is ill prepared to handle the hundreds of thousands of HIV cases. The medical facilities I saw were dark (to lower electricity bills), understaffed, and in shabby condition. The few patients admitted to hospitals bring their own sheets, towels, toilet paper, and medicine, and opiate-addicted AIDS patients often smuggle in drugs. Most people living with HIV are reluctant to seek assistance from public health facilities for fear they will be turned over to the authorities or stigmatized by hospital staff.

The current policies in Russia and Ukraine are driving underground the people who most need help. Unless the governments acknowledge the severity and reasons behind the HIV epidemic, this tragedy will only deepen.

—John Ranard, March 2005