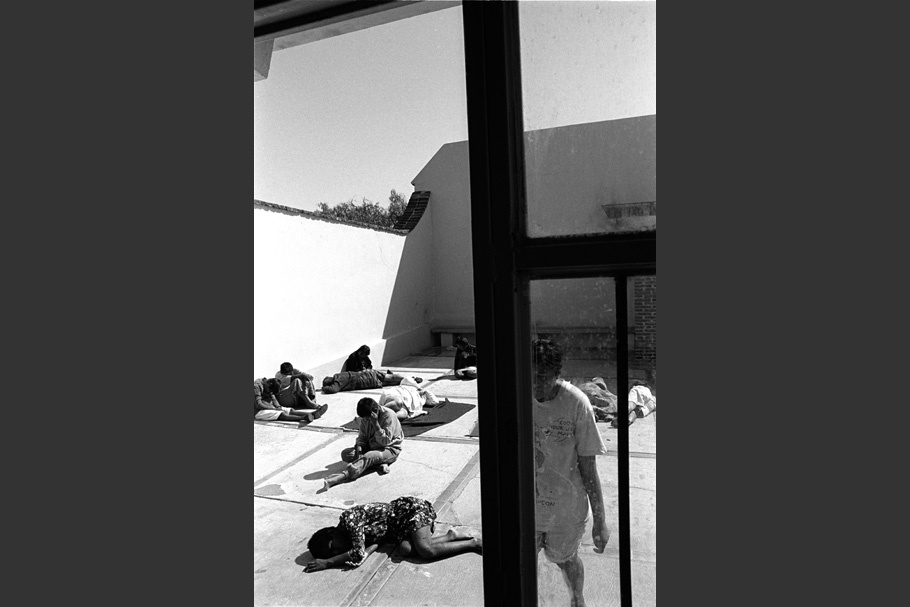

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-001

Asuncion, Paraguay.

The 46 residents of Pavilion Two pull their mattresses into the courtyard, so that their sleeping rooms can be hosed down.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-002

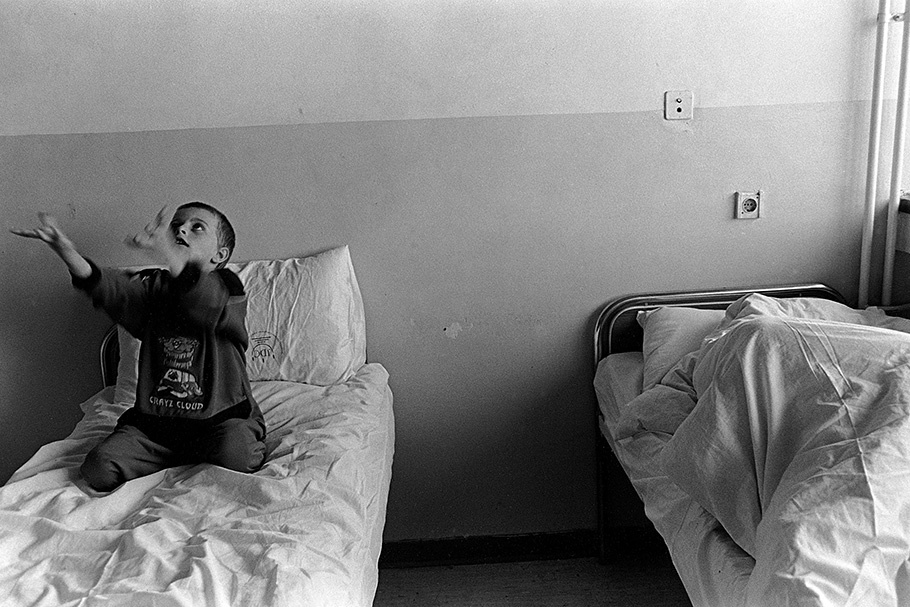

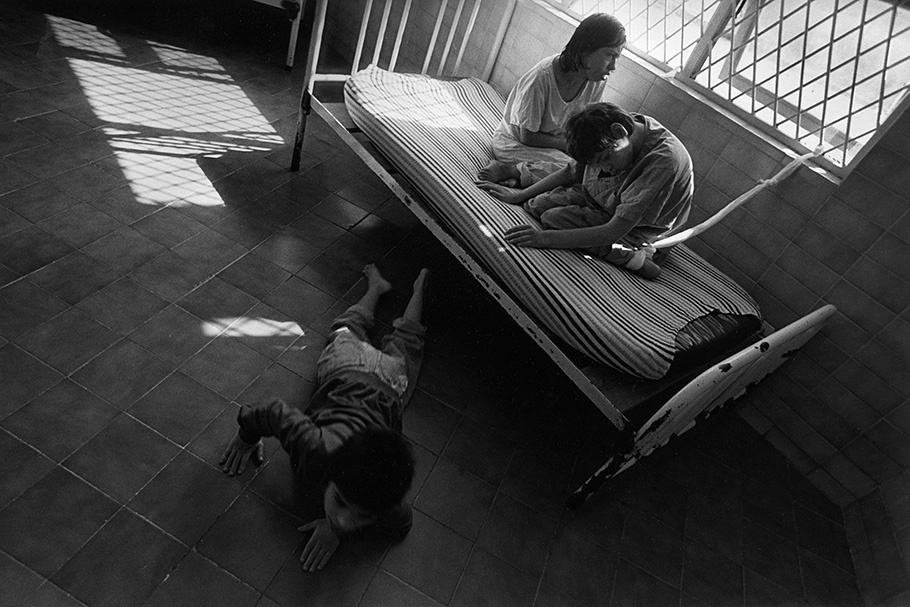

Budapest, Hungary.

A child is allowed to live on a locked ward of a state hospital with his mentally troubled and reclusive mother.

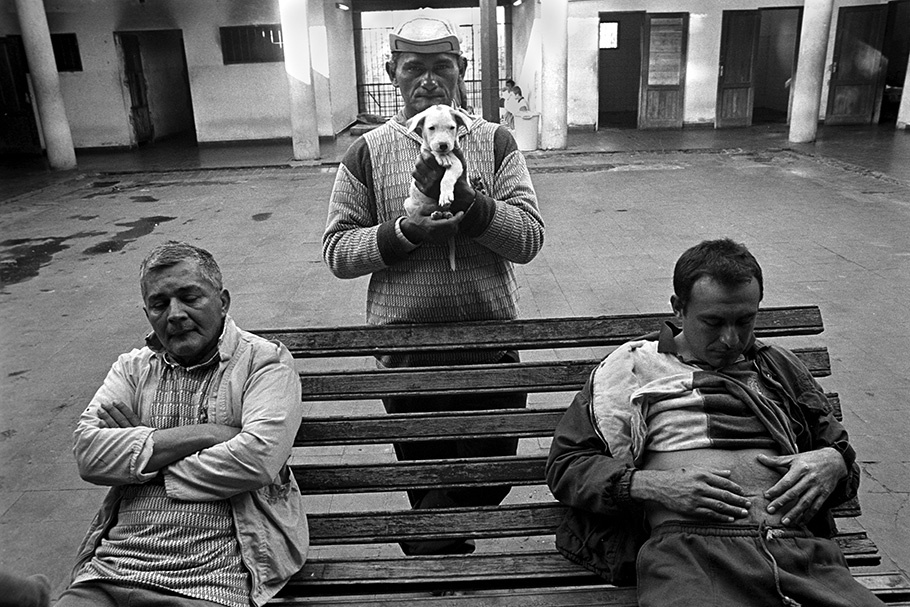

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-003

Asuncion, Paraguay.

A longtime patient at the Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital hopes to adopt a puppy that had wandered into the ward.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-004

Asuncion, Paraguay.

Though the majority of patients live heavily medicated, solitary lives, a few patients form relationships and attempt to care for one another.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-005

Hidalgo, Mexico.

At Ocaranza, female attendants often bathe male patients and male attendants bathe female patients. The water is icy cold and there are no towels.

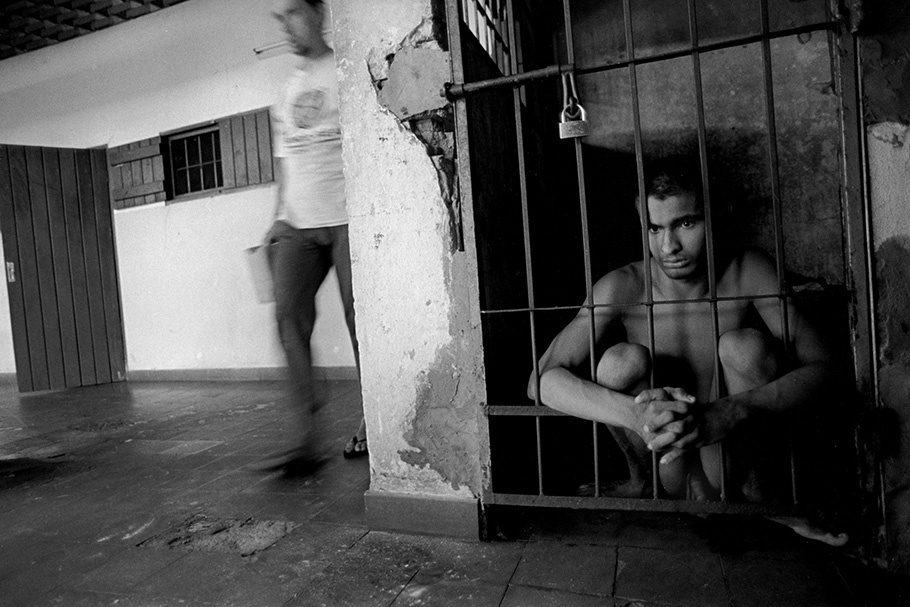

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-006

Asuncion, Paraguay.

Abandoned at birth, 17-year-old Julio has been held for six years in a tiny cell that has a hole in the floor for a toilet and no electricity.

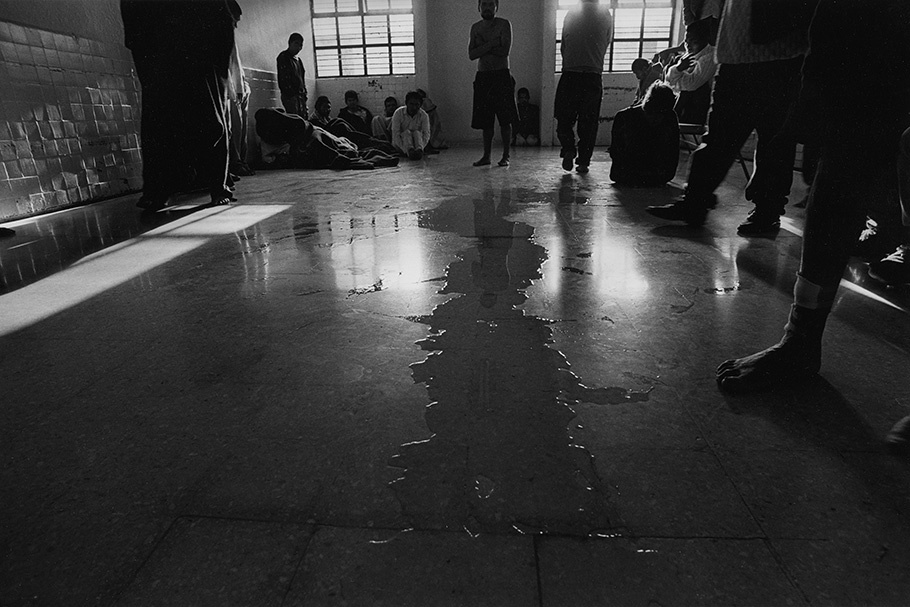

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-007

Hidalgo, Mexico.

In the early morning, a stream of urine runs through the men's ward at the Ocaranza Psychiatric Institution.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-008

Guadalajara, Mexico.

In the children's ward at Jalisco, children are housed with adults, tethered to the bars of their cells, and covered with flies.

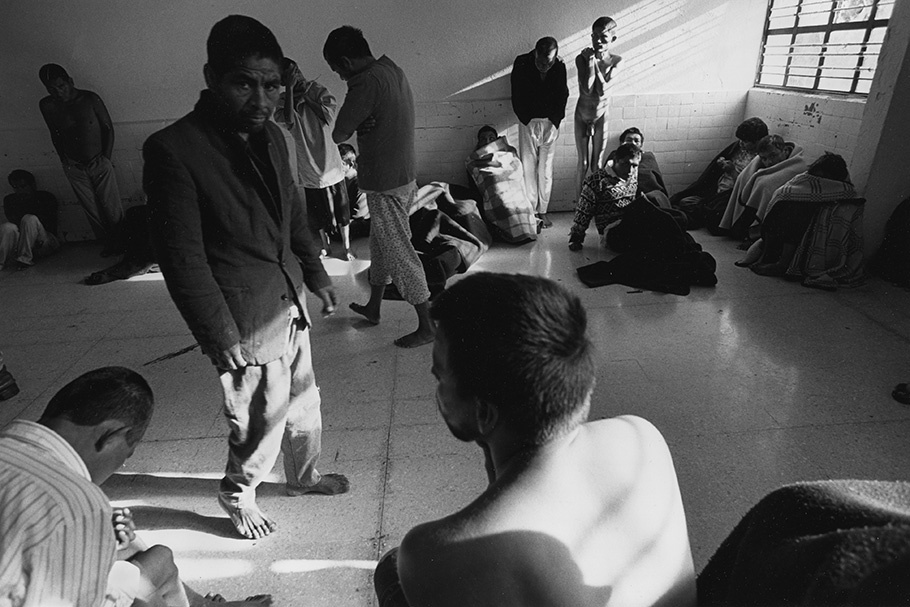

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-009

Hidalgo, Mexico.

In the early morning in Ocaranza, patients begin pacing—back and forth, up and down—as if they have somewhere to go.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-010

Asunción, Paraguay.

Patients considered “difficult” are held in locked cells, while other women, often unclothed, pace up and down in the courtyard.

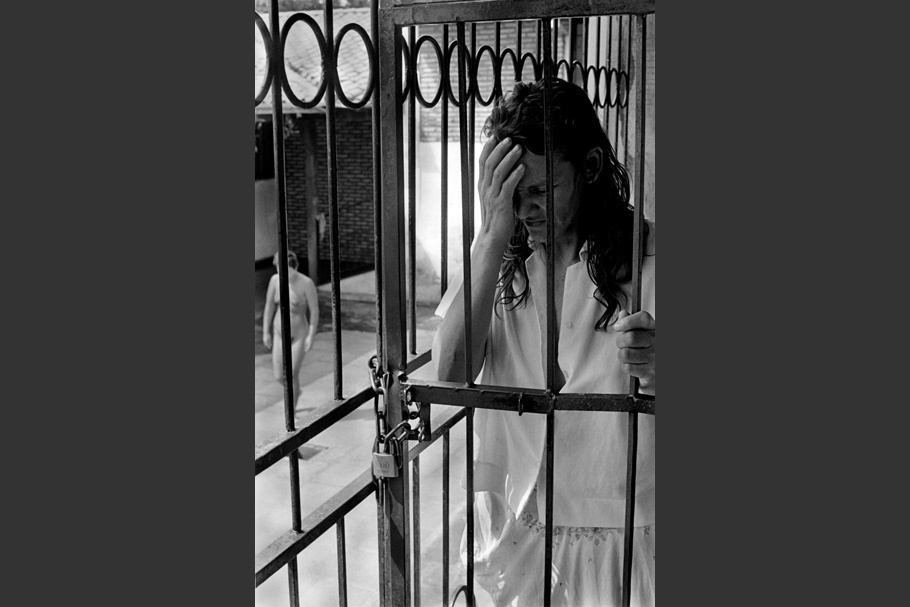

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-011

Asunción, Paraguay.

A woman deemed “unreachable” is kept away from other patients in a padlocked cell.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-012

Hidalgo, Mexico.

An elderly patient, believed to have Alzheimer’s, sits unattended and shivering in the morning cold.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-013

Hidalgo, Mexico.

Because there are too few attendants and few, if any, treatment programs, patients are left to fend for themselves.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-014

Asunción, Paraguay.

Kept most of every day in a six by nine foot cell, 17-year-old Julio is allotted a few hours in a bare, but sunny space.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-015

Asunción, Paraguay.

One of more than two hundred women at the Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital peers through makeshift bars.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-016

Guadalajara, Mexico.

A patient at Jalisco, a state psychiatric center, presses against the locked door, looking for attention.

20050316-richards-mw10-collection-017

Kapan, Armenia.

An iron gate separates the Regional Psychiatric Dispensary from the adjoining tuberculosis clinic.

Eugene Richards was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Following college, he joined AmeriCorps: VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) and was assigned to eastern Arkansas, where he helped found a social service organization and community newspaper. After the publication of his first book, Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta (1973), he began working as a freelance photographer for such publications as Life and The New York Times Magazine. Richards’ subsequent books include Dorchester Days (1978), a portrait of the Boston neighborhood where he was born; Exploding Into Life (1986), which chronicles his first wife Dorothea’s struggle with breast cancer; Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue (1994), a study of the impact of hardcore drugs on American cities; Stepping Through the Ashes (2002), an elegy to those who lost their lives on September 11, 2001; and The Fat Baby (2004), which is a collection of 15 textual and photographic stories produced during the past dozen years. Among the numerous honors Richards has received are the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Award, a Guggenheim fellowship, the Overseas Press Club’s Olivier Rebbot Award, and the Robert F. Kennedy Lifetime Achievement Journalism Award for coverage of the disadvantaged.

Eugene Richards

Few human beings are subject to as much misunderstanding, cruelty, and neglect as the mentally ill and the developmentally disabled. People with mental disabilities are often abandoned or hidden away in public institutions, which are grossly overcrowded and filthy, and which offer little in the way of medical care or training. The developmentally disabled are mixed in with the mentally ill, very young people with the very old, the physically unhealthy with the healthy. Heavily medicated and deprived of dental care, proper nutrition, education, and counseling, the mentally disabled have almost no chance of living productively and safely within these institutions and little opportunity of ever leaving.

First on assignment and then as a volunteer for the human rights group Mental Disability Rights International, I reported on conditions in mostly state-run psychiatric facilities. Now when I hear the words “psychiatric hospital,” I see barred windows, locked wards, gray walls, blank stares, drugged people lying on the floor.

Mention Ocaranza in Hidalgo, Mexico, and I will tell you that the men’s ward had a wide stream of urine running through it, that it was 48 degrees inside the hospital the morning we pushed our way in, and that at night there was only one nurse on duty for 110 patients. The women’s ward was as cold, damp, and bare as the men’s. I photographed an elderly woman with what was probably Alzheimer’s tied to a wheelchair and shivering in her thin nightdress, then a 17-year-old girl who, because she persisted in shoving her hand down her throat, spent most of every day in a straitjacket.

Mention Jalisco in Guadalajara, Mexico, and I will tell you about the children’s ward, where kids, often housed with adult patients, were left lying on mats covered with urine and feces or tied to the bars of their cells, eating their own excrement, and covered with flies.

Mention the Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital in Asunción, Paraguay, and I will tell you about two 17-year-old boys, Julio and Ramón, abandoned at birth, who were held for six years in six-by-nine-foot cells that had holes in the floors for toilets, no electricity, dirty blankets, and openings in the barred doors through which their food was passed.

Mention the Shtime Special Institution in Kosovo, and I will tell you that that is where I encountered patients curled up and barely conscious on floors soiled with waste. I will tell you about the female patients, women of all ages, who spoke in hushed voices of having been raped inside the institution. One woman was raped after attendants locked her in a room with a male patient, in order to “calm her down.”

The cruelty and mistreatment I witnessed in one place I witnessed in all—in Paraguay, in Kosovo, in Hungary, in Argentina, in Armenia, in Mexico—as if there is a global agreement that you can do things to people classified mentally or developmentally disabled that you couldn’t possibly do to other people.

—Eugene Richards, March 2005