20020409-glyadyelov-mw06-collection-001

June 1997. Odessa, Cheremushki. 6:00 a.m.

20020409-glyadyelov-mw06-collection-002

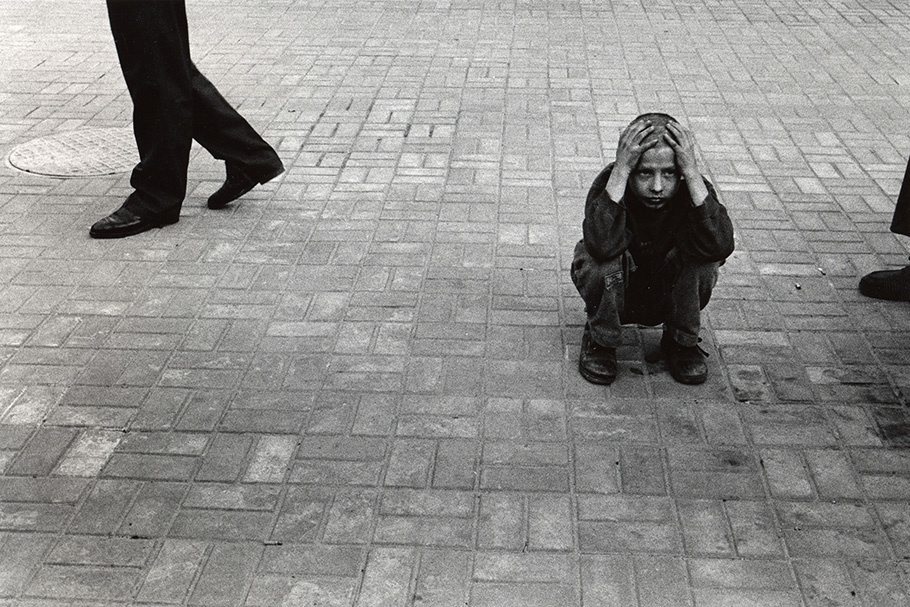

Street boy detained by the police is waiting to be delivered to the detention center.

September, 1998. Khreschatyk St., Kiev.

20020409-glyadyelov-mw06-collection-003

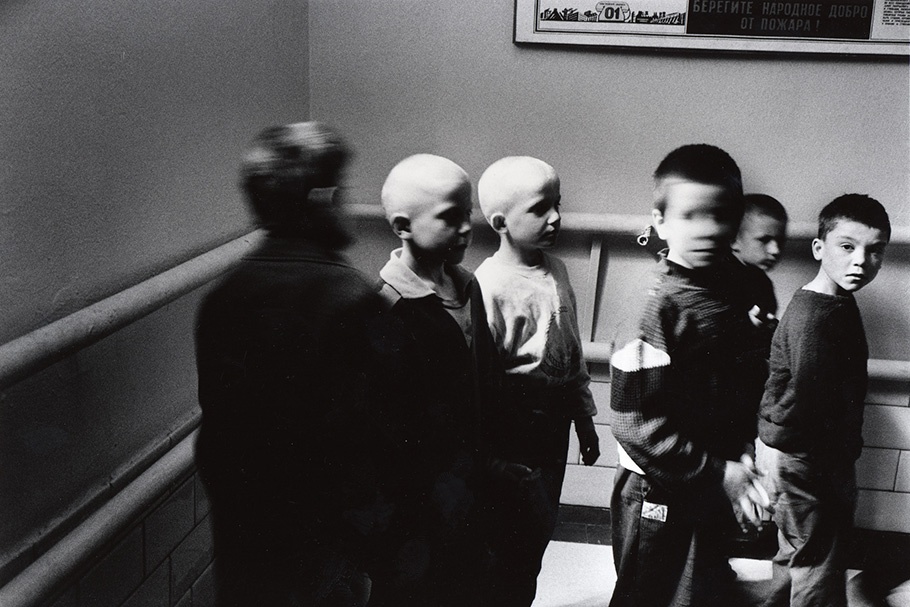

Kiev, a detention center for stray children. Lining up to the dining room. At the right is a little boy that I will meet four months later in the Odessa detention center.

April 1997.

20020409-glyadyelov-mw06-collection-004

June 1997. Odessa, Privoz market.

20020409-glyadyelov-mw06-collection-005

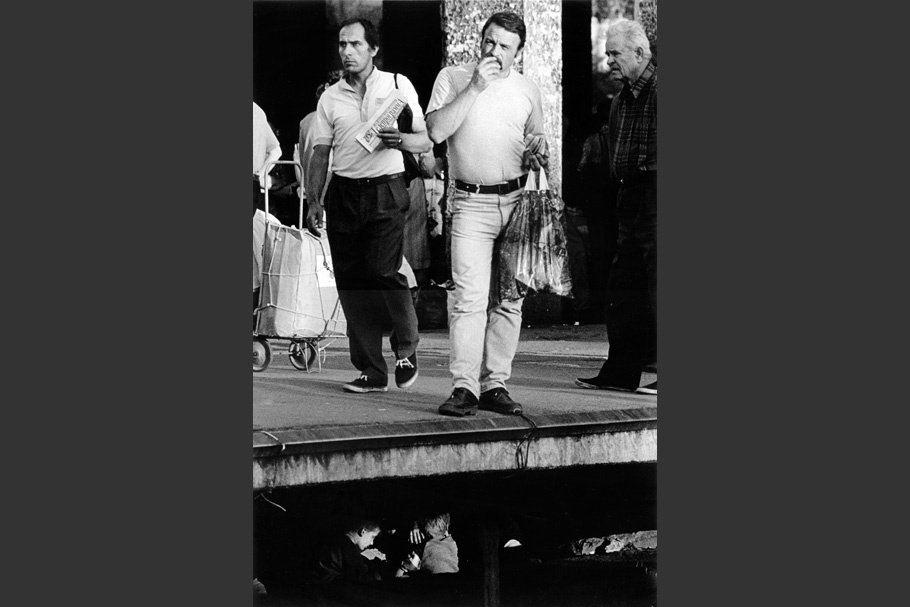

December 1996. Kiev, Lybidska subway station.

20020409-glyadyelov-mw06-collection-006

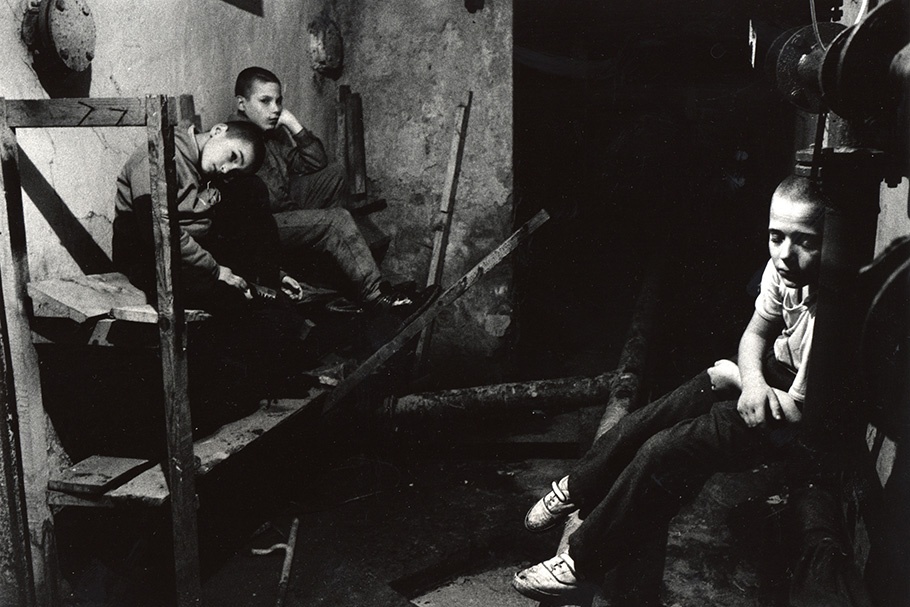

Slava, Maksim and Dima rest in the basement of a residence. The previous morning they were picked-up by police in another building, but managed to escape on the way to the police station.

October 1996. Kiev. 1:30 a.m.

20020409-glyadyelov-mw06-collection-007

Nine-year-old addicts Zhenya and Vitya inhale the fumes of synthetic glue.

November, 1996. Kiev, Petrovka subway station.

20020409-glyadyelov-mw06-collection-008

Homeless boys, living under the platform, share food.

August, 1996. Kiev, Svyatoshin railway station.

Aleksandr Glyadyelov was born in Legnitz, Poland, in 1956, into the family of a Soviet Army officer. Since 1974, he has lived in Kiev.

He studied optics at the Kiev Polytechnical Institute, graduating in 1980. Having studied photography independently since the mid 1980's, he began working as a professional freelance photojournalist in 1989. Glyadyelov has traveled frequently throughout the former Soviet Union taking photographs in Ukraine, Russia, Moldova, Kyrgyztan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Latvia, Poland, the Czech Republic, France, and the United States. He covered the armed conflicts in Moldova, Nagornij Karabakh, and Chechnya.

Since 1996, Glyadyelov has concentrated on two long-term documentary photography projects in the Ukraine: socially abused children, and the HIV/AIDS epidemic among intravenous drug users.

In 2001, working with the humanitarian organization Doctors Without Borders, Glyadyelov began the project Without the Mask about the Tuberculosis epidemic in Russian prisons.

He was awarded the Grand-Prix of Ukrpressphoto-97, Hasselblad Prize at the European Photography contest in Vevey (Switzerland) in 1998, and Mother-Jones International Fund 2001.

Glyadyelov's photography has been used by international organizations such as Doctors Without Borders, UNAIDS, and UNICEF.

Aleksandr Glyadyelov

On a dark, fall evening in 1996, I stood with a group of street kids—three boys and two girls—in front of an expensive shop. I’d met the girls the previous summer. I’d met the boys several days earlier. Two of the boys were brothers and, together with their friend, had been living on the street for two years, preferring it to life with their alcoholic parents. They’d promised to show me the place where they spent their nights. Out of the blue, one of the boys, Serezha, asked me: “Uncle Sasha, how old are you?”

“I’m 40 years-old,” I replied.

He thought a bit, then said: “You had already been in this world for thirty years when I entered it.”

With my voice suddenly weak, I asked them: “And how has this world treated you?”

“Bad,” they said at once.

Struggling to find the right words, I continued: “Well, would it be better not to live in this world?”

“It’s probably better to live,” said Serezha, after a moment of contemplation. Everyone agreed.

“Sometimes life can be interesting,” explained nine-year-old Sasha, and spat on the ground. Everyone agreed again.

I photographed the children over the next month until, without warning, they changed sleeping quarters, and I lost them. I would meet them again two years later, only to lose them after three days.

The first images of this project were taken six years ago and I still can’t decide when it will be complete. Some of the prints are spontaneous; others are the result of endless research. The rest are the product of long-lasting, trusting relationships with the children.

The endless poverty experienced by the majority of the Ukranian population is humiliating and many are forced to survive in degrading ways. It pushes kids out of their homes onto the streets where they spend their days searching for a crust of bread, and their nights looking for a place to sleep. Some prefer the violence of the streets to homes filled with alcohol and drugs. Even kids as young as three and four end up on the streets.

Basements and begging, small thefts and underground heating pipes, alcohol and violence (often sexual), sniffing synthetic glue, drugs, cruel treatment by the police—these are inevitable parts of the daily struggle. Kids disappear; others take their place—each less trusting and more desperate than the next.

The government views these children as statistics, but when I look through my viewfinder I see the individual. The children in these pictures are not living a normal life; it is a life without happiness, so there is no happiness in my pictures.

—Aleksandr Glyadyelov, April 2002