20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-001

Dembel Jumpora: Baby Feet

Halima Balde holds her first child just days after he was born. The naming ceremony does not take place until a week after birth because of the high rate of child mortality.

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-002

Dembel Jumpora: Circumcision

Five-year-old Awa Balde clings to her mother moments after being circumcised. Girls can be subjected to circumcision from the time they are small babies through young adulthood.

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-003

Dembel Jumpora: Washing

Alio Balde scrubs his back in front of the touffe.

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-004

Dembel Jumpora: Mango Tree

Villagers are drawn to the central point of their village: the mango tree. Everyone congregates beneath the shade of the enormous tree to escape the sweltering heat of the sun.

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-005

Dembel Jumpora: Dinner

Children eat the staple diet of rice from a communal bowl. During the end of the dry season, there is little to eat and many children will have one meal of rice each day.

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-006

Dembel Jumpora: Sunrise

Khady Balde warms herself in the early morning sun.

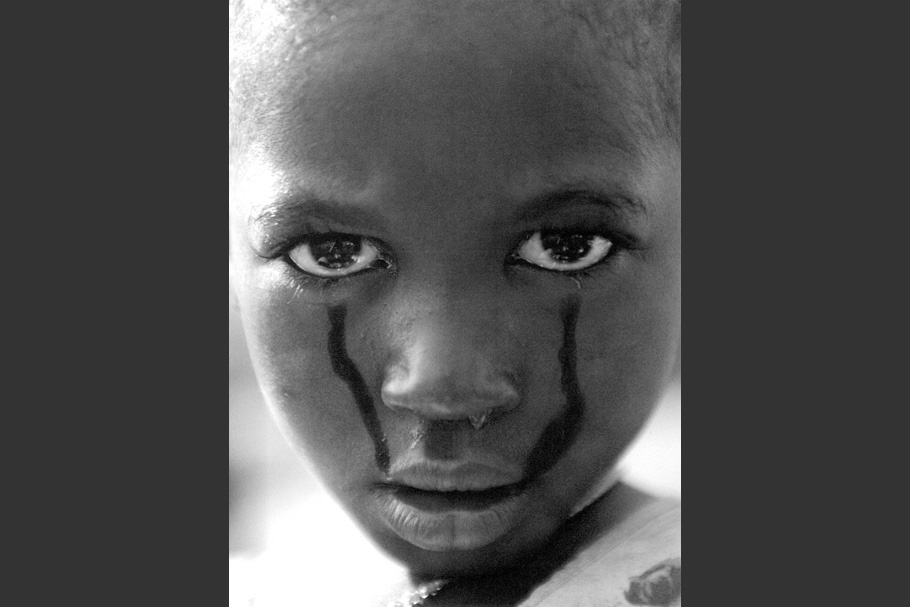

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-007

Dembel Jumpora: Tears

In a culture where the opportunities for women to be honored, celebrated, and recognized are few, circumcision is disproportionately significant, in spite of the pain it brings.

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-008

Dembel Jumpora: Donkey

Adema watches her brother prepare to take the family’s donkey to town where he will sell hand-made brooms. The economy for most of the country is based on subsistence farming and small trade.

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-009

Dembel Jumpora: Dive

Dembel Jumpora is nestled in the eastern part of the country where the climate is hot and humid. By the end of the dry season, there is little water to be found above ground. The children take advantage of the rains and spend a great amount of time swimming in the touffe.

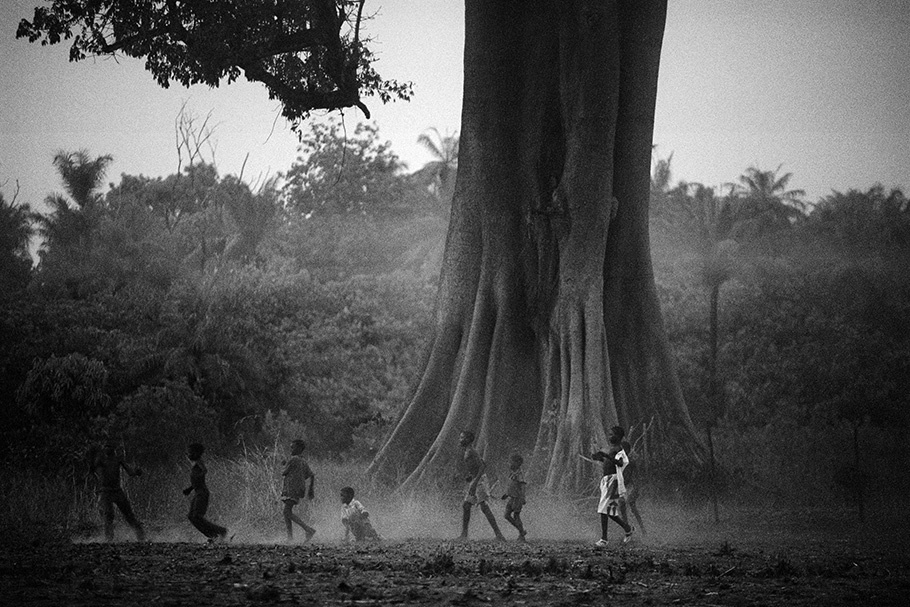

20020409-vitale-mw06-collection-010

Bontang Tree

Boys play soccer underneath an enormous Bontang tree. Though the Fulani are a Muslim tribe, they also believe that this tree has a spirit. This mixture of animist beliefs and Islamic law creates a society that has a great respect for the land around them, the supernatural world, and the laws of the Koran.

Ami Vitale was born in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, in 1971. She majored in international studies with a concentration in visual communications at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. As an undergraduate, she received the John Hope Franklin Documentary Grant in 1993 to continue her work documenting the changing communities of the rural South. She was also the National Press Photographer's Joseph Ehrenreich Grant recipient in 1993 and received awards from NPPA's College Photographer of the Year contest.

After she graduated, Vitale began working as an editor for Associated Press in New York and Washington D.C. and eventually left in 1997 for the Czech Republic where she lived for two and a half years. She covered the Balkan conflict during this period but moved to continue her work in Africa. In 2000, she was awarded the Alexia Foundation's grant to promote peace and world understanding which allowed her to continue her work documenting traditional Muslim communities in Guinea-Bissau. For the last two years, her photographs and stories from events in India, Europe, the Middle East and Africa have appeared in publications including Time, Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, BusinessWeek, The Economist, The Guardian, The Telegraph Sunday Magazine, USA Today, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Financial Times and MSNBC among others. She has also received international awards from the Czech Republic, Canada and China. Vitale is currently based in India.

Ami Vitale

There are rare moments when one is able to capture a vision of the past and a look into the future. I have been fortunate to observe a group from the Fulani tribe after they settled in the West African country of Guinea Bissau. Having abandoned their nomadic tribal roots to become farmers, the Fulani struggle to adapt to a world that has thrust itself onto them in uncompromising ways.

This is the story of the life of one Fulani family, and the age-old rites that persist and those that die in an Africa that few can ever imagine. The Fulani are Muslim, which sets them apart from most other ethnic tribes in Guinea Bissau. Islamic traditions such as female and male circumcision, five prayer times a day, the Islamic calendar and multiple wives have combined with local beliefs and traditions to produce a brand of Islam that is unique to this area and its people. From the belief in tree spirits to the use of traditional medicine or "voodoo," the mixing of cultures that took place centuries earlier has produced a society that blends a unique spiritual universe with the often brutal daily existence of the physical world.

To an outsider, the village may appear to be a place where people live simply, struggling to survive. While partly true, the social hierarchy and politics among members of the tribe are surprisingly complex. The village is a place where people’s lives are caught up in a rigorous power struggle that is influenced by the past, the present, and the promise of the future. It is a place where the dead and unborn play powerful roles in the fate of the living.

On June 7, 1998, ousted General Ansumane Mane led a military revolt against President Joao Bernardo "Nino" Vieira, which exploded into a full-scale civil conflict, and ultimately concluded with the near collapse of the region when neighboring countries got involved. The fighting centered mostly in the capital, Bissau, sending nearly all of its 300,000 inhabitants upcountry to escape. With a dwindling food and water supply, a massive internally displaced population, and diseases such as cholera and malaria spreading, Guineans suffered their worst humanitarian crisis since the war for independence that ended in 1974.

My prior visits to the remote village of Dembel Jumpora left a lasting impression of a land overlooked by modern development, but warmed by an intricate Muslim culture. In December 2000, I returned to the village and found the villagers were able to treat the war as they treat many difficulties in life—as phenomena over which they have no control. In addition to documenting this vanishing culture’s wealth of traditions, it was my hope to present a meaningful look into their lives, showing the dignity and humor that exists in their struggle to provide for their children in a place that can be unforgiving to the body and soul.

—Ami Vitale, April 2002