20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-001

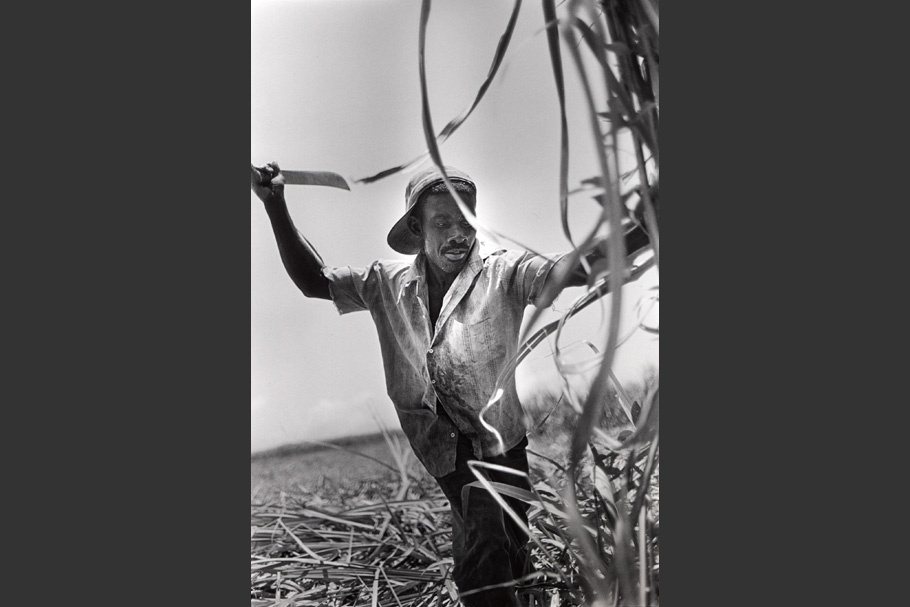

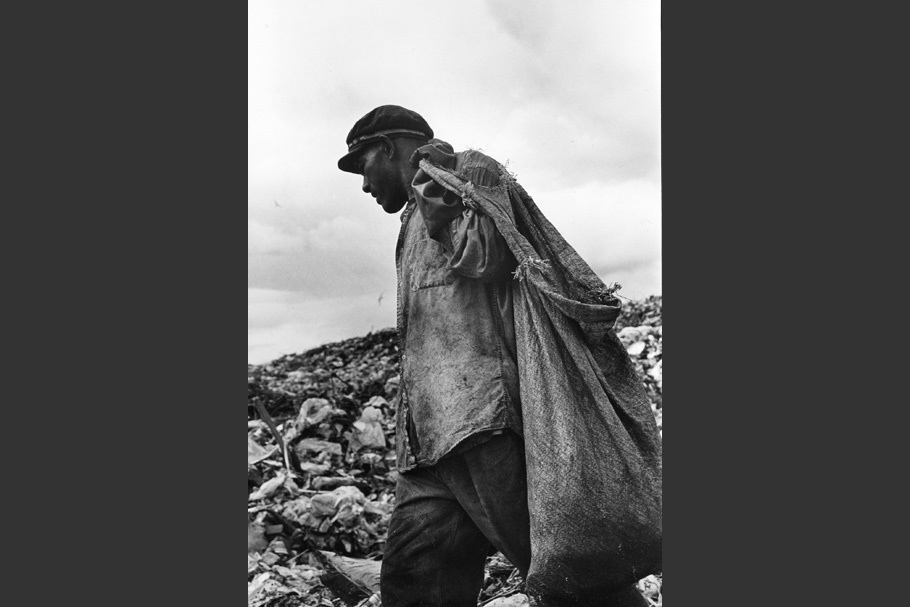

While many still work from sunup to sundown without shade or water in the cane brakes, the transition from a sugar economy to one based on tourism and the development of industrial zona francas has led to desperation among the disenfranchised cane cutters. Many of them now eke out an existence as buzos (divers), scouring the stinking town dumps for glass, paper, metal, and even rotten food—anything they can sell.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-002

While many still work from sunup to sundown without shade or water in the cane brakes, the transition from a sugar economy to one based on tourism and the development of industrial zonas francas has led to desperation among the disenfranchised cane cutters. Many of them now eke out an existence as buzos (divers), scouring the stinking town dumps for glass, paper, metal, and even rotten food—anything they can sell.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-003

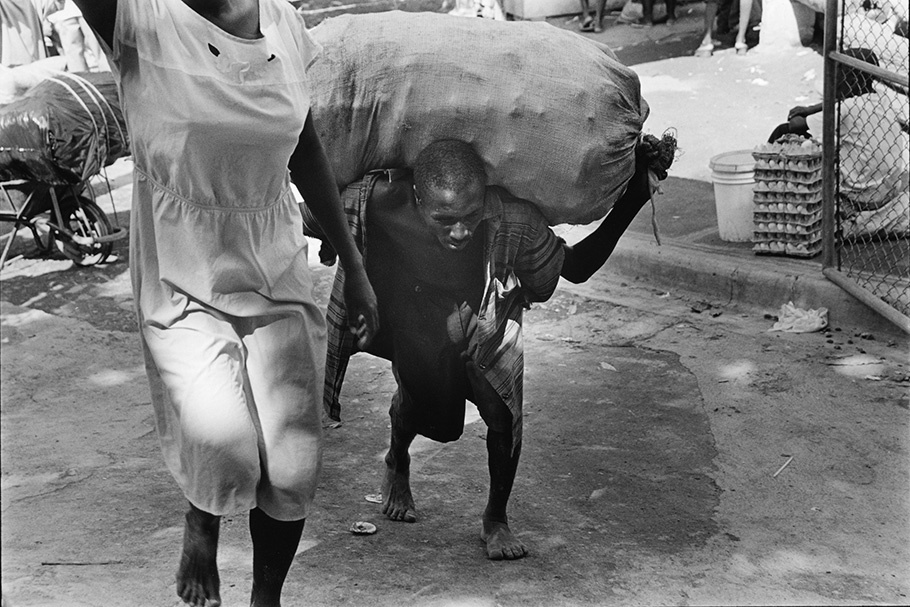

Scenes from the border at Dajabon. On market days, Haitians come to trade handmade objects, cheap shoes, clothing, and other items for much-needed food supplies. They also cross illegally in search of work. To avoid the long line at the customs post, they gather in the Rio Massacre, waiting either to bribe a guard or run past when his back is turned. Occasionally, the game turns ugly: two days after my visit, guards shot five Haitians who panicked and tried to charge over the border.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-004

Scenes from the border at Dajabon. On market days, Haitians come to trade handmade objects, cheap shoes, clothing, and other items for much-needed food supplies. They also cross illegally in search of work. To avoid the long line at the customs post, they gather in the Rio Massacre, waiting either to bribe a guard or run past when his back is turned. Occasionally, the game turns ugly: two days after my visit, guards shot five Haitians who panicked and tried to charge over the border.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-005

Scenes from the border at Dajabon. On market days, Haitians come to trade handmade objects, cheap shoes, clothing, and other items for much-needed food supplies. They also cross illegally in search of work. To avoid the long line at the customs post, they gather in the Rio Massacre, waiting either to bribe a guard or run past when his back is turned. Occasionally, the game turns ugly: two days after my visit, guards shot five Haitians who panicked and tried to charge over the border.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-006

A man lies in his barrack, dying of hunger in Batey Santa Rosa. Abandoned by his family and by the other inhabitants of the batey, he waits patiently for death to end his suffering. Among the worst bateys are the ones around Monte Plata, where the cane grows wild but the ingenios have long ceased to operate, and there is no work.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-007

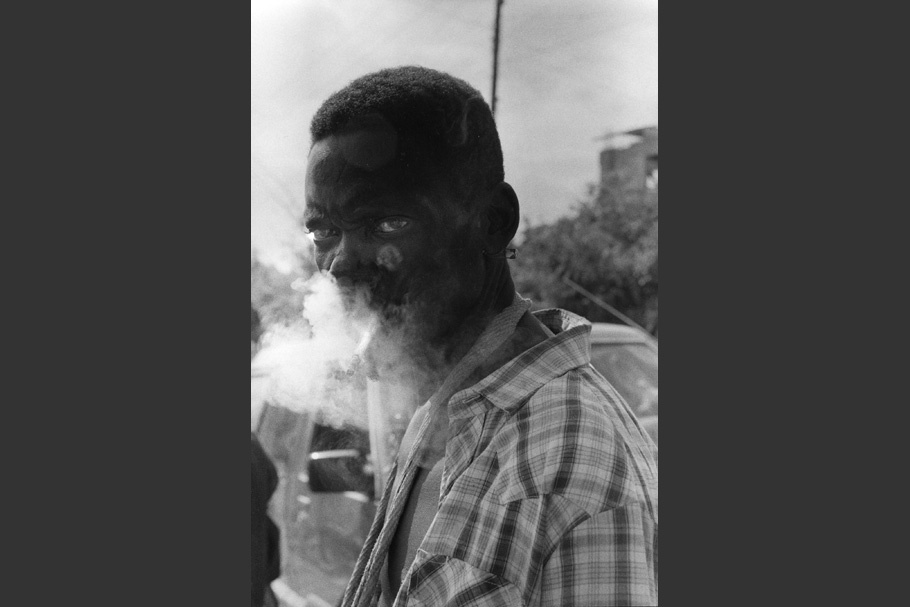

Among the group from El Chicharron was this inebriated palero, eyes bloodshot after days of drinking and dancing and drumming, his stern features the very image of Chango.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-008

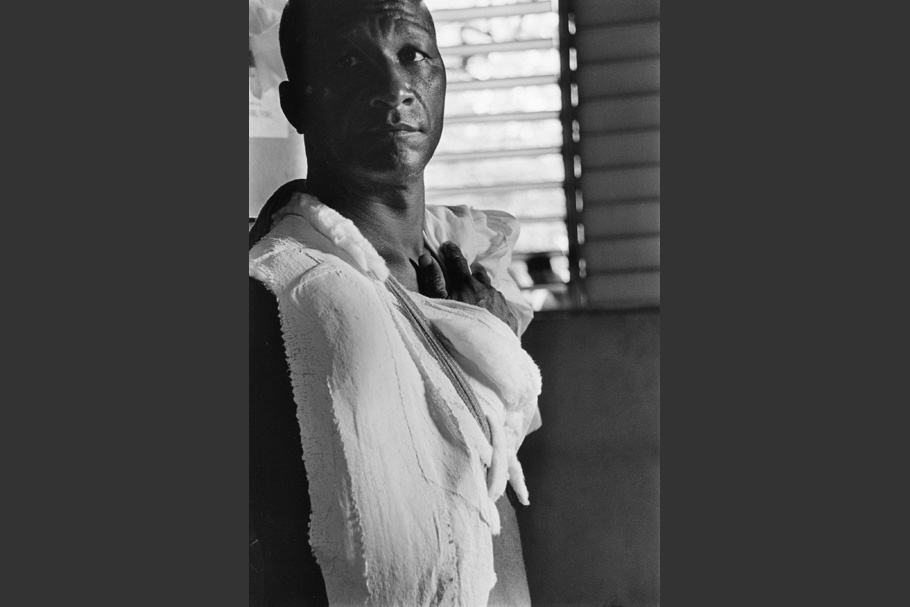

An injured cane worker at a clinic run by the Batey Relief Alliance, one of the few organizations working to help these forgotten people. A bracero without his arm (brazo), which is both his means of sustenance and the source of his social identity, is truly in limbo.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-009

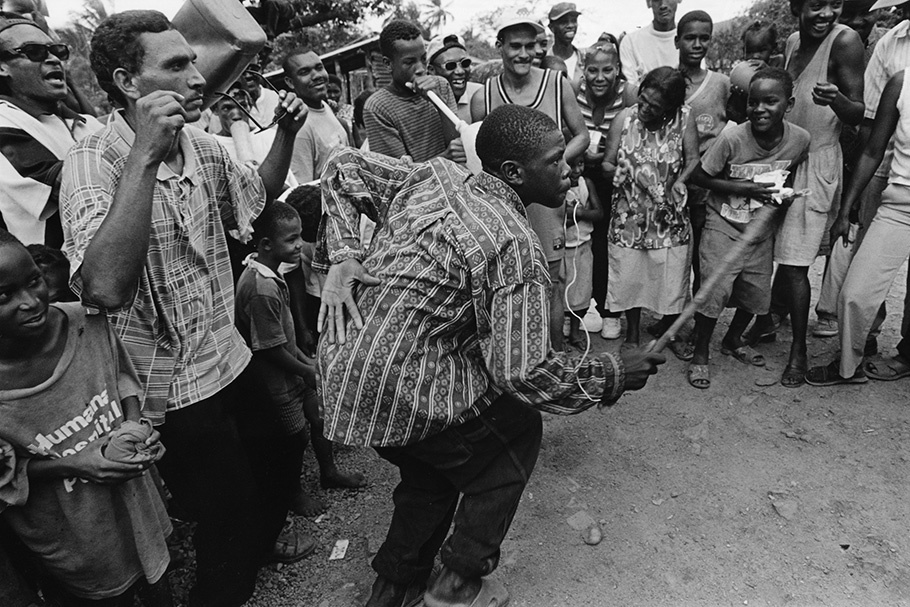

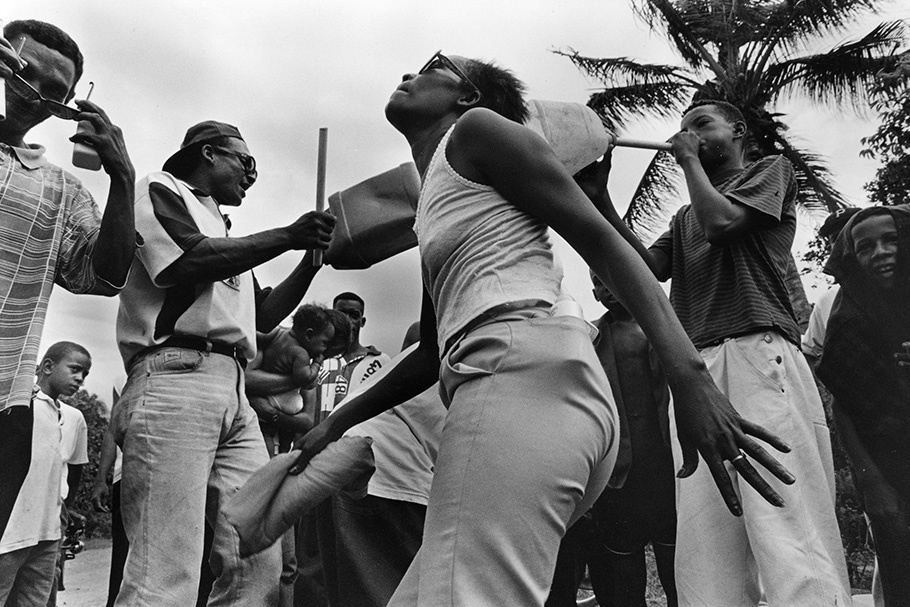

During Holy Week, Gagá bands (“rara” in Kreyol) parade down the roads, integrating carnival, brujeria, vodú, Christianity, ecstatic dance, and the martial arts. This eclectic mix is synthesized by a unique form of percussive music, composed of futubas (vaksins in Kreyol, made from bamboo or industrial tubing), trompetas (from tin cans or even clorox bottles), whistles, maracas, guiras, and palos (conga-style drums used to invoke the “saints”). The dispossessed take control of the road, exact tribute from homeowners and shopkeepers along the way, and invoke a cosmic order that supercedes the ingenios. With a mix of Kreyol and Dominican slang, they sing about the powers of the gods, the plantations, the politicians, the clitoris, and the phallus.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-010

During Holy Week, Gagá bands (“rara” in Kreyol) parade down the roads, integrating carnival, brujeria, vodú, Christianity, ecstatic dance, and the martial arts. This eclectic mix is synthesized by a unique form of percussive music, composed of futubas (vaksins in Kreyol, made from bamboo or industrial tubing), trompetas (from tin cans or even clorox bottles), whistles, maracas, guiras, and palos (conga-style drums used to invoke the “saints”). The dispossessed take control of the road, exact tribute from homeowners and shopkeepers along the way, and invoke a cosmic order that supercedes the ingenios. With a mix of Kreyol and Dominican slang, they sing about the powers of the gods, the plantations, the politicians, the clitoris, and the phallus.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-011

During Holy Week, Gagá bands (“rara” in Kreyol) parade down the roads, integrating carnival, brujeria, vodú, Christianity, ecstatic dance, and the martial arts. This eclectic mix is synthesized by a unique form of percussive music, composed of futubas (vaksins in Kreyol, made from bamboo or industrial tubing), trompetas (from tin cans or even clorox bottles), whistles, maracas, guiras, and palos (conga-style drums used to invoke the “saints”). The dispossessed take control of the road, exact tribute from homeowners and shopkeepers along the way, and invoke a cosmic order that supercedes the ingenios. With a mix of Kreyol and Dominican slang, they sing about the powers of the gods, the plantations, the politicians, the clitoris, and the phallus.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-012

During Holy Week, Gagá bands (“rara” in Kreyol) parade down the roads, integrating carnival, brujeria, vodú, Christianity, ecstatic dance, and the martial arts. This eclectic mix is synthesized by a unique form of percussive music, composed of futubas (vaksins in Kreyol, made from bamboo or industrial tubing), trompetas (from tin cans or even clorox bottles), whistles, maracas, guiras, and palos (conga-style drums used to invoke the “saints”). The dispossessed take control of the road, exact tribute from homeowners and shopkeepers along the way, and invoke a cosmic order that supercedes the ingenios. With a mix of Kreyol and Dominican slang, they sing about the powers of the gods, the plantations, the politicians, the clitoris, and the phallus.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-013

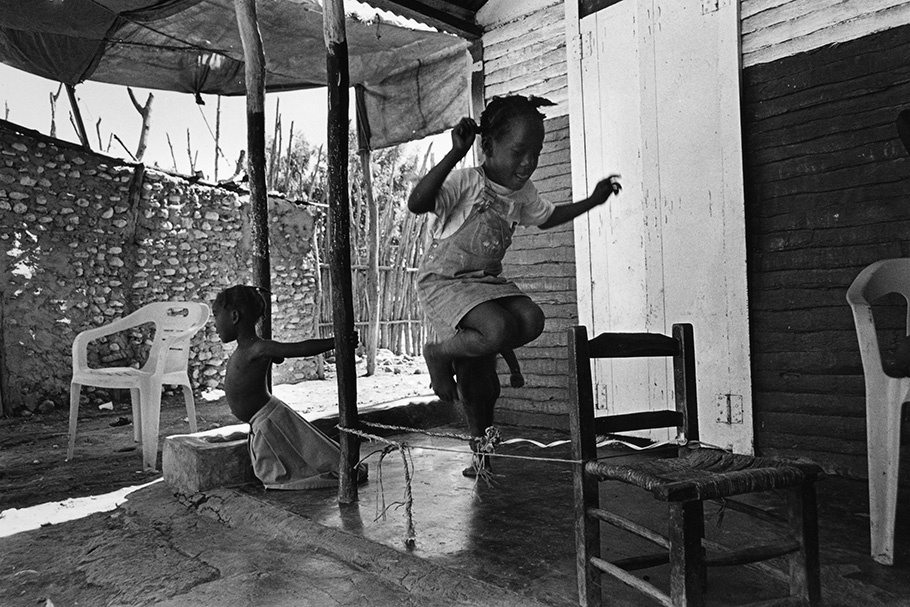

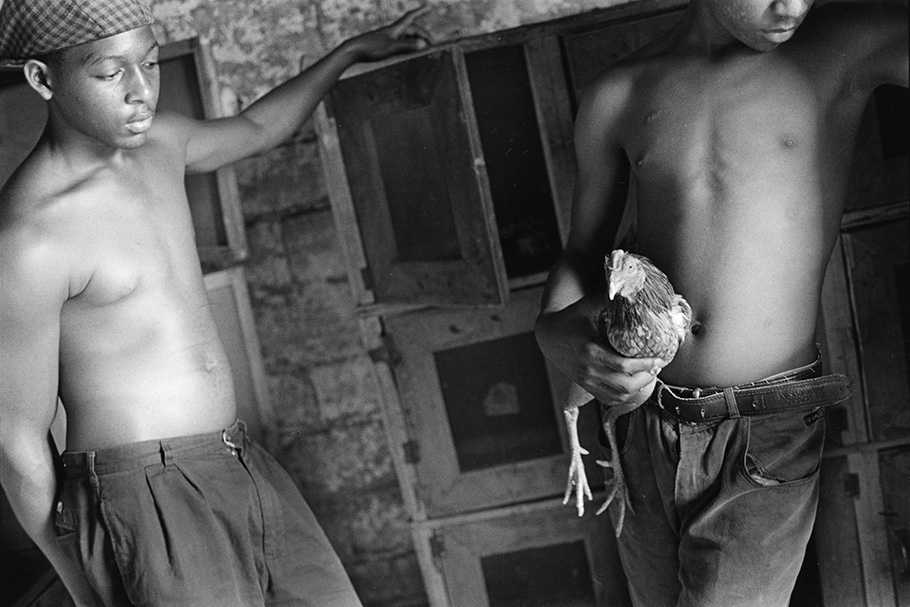

In many bateys there is no school and no work available, so the kids are free to do as they please. In Batey Payabo, a young man escapes the heat at the local swimming hole. A few miles away, two galleros tend to the coop: unemployed and unheeded, the cockfighter counts on his vocation and the prowess of his gallos to distinguish him as someone to be reckoned with. Near Barahona, in Batey Algodon, which is nothing more than a few shacks and a road scratched out in the hot dust, a girl skips rope, mindless of the “shades of the prison-house” closing in on her.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-014

In many bateys there is no school and no work available, so the kids are free to do as they please. In Batey Payabo, a young man escapes the heat at the local swimming hole. A few miles away, two galleros tend to the coop: unemployed and unheeded, the cockfighter counts on his vocation and the prowess of his gallos to distinguish him as someone to be reckoned with. Near Barahona, in Batey Algodon, which is nothing more than a few shacks and a road scratched out in the hot dust, a girl skips rope, mindless of the “shades of the prison-house” closing in on her.

20020409-anderson-mw06-collection-015

In many bateys there is no school and no work available, so the kids are free to do as they please. In Batey Payabo, a young man escapes the heat at the local swimming hole. A few miles away, two galleros tend to the coop: unemployed and unheeded, the cockfighter counts on his vocation and the prowess of his gallos to distinguish him as someone to be reckoned with. Near Barahona, in Batey Algodon, which is nothing more than a few shacks and a road scratched out in the hot dust, a girl skips rope, mindless of the “shades of the prison-house” closing in on her.

Born and raised in New York, Jon Anderson studied and taught literature at Columbia University before switching to photojournalism. He trained himself by working as a lab and teacher’s assistant at the International Center of Photography, and thereafter worked independently on a variety of subjects in New York. In 1996 he joined the Black Star Agency and produced essays on homelessness, poverty, pediatric AIDS, and prostitution. His work has appeared in such publications as Newsweek, Newsweek in Spanish, Vogue, Emerge, as well as a variety of texts. He recently exhibited photographs at the United Nations.

Drawn to ways of life that have abided for centuries, he has traveled in Asia and South America, photographing, among other things, an ancient Shaivite ashram in Varanasi, where boys are trained to become priests; a group of Hijras (eunuchs) from Delhi; and Brazilian Macumba in the favelas, which sparked an ongoing interest in the culture of the African diaspora.

After covering the historic Dominican elections of 1994 and 1996, Anderson eventually took up residence in Santo Domingo in order to work on two books, one documenting the problem of the bateys, and the other, a kind of novel in pictures entitled The Good Life, depicting a culture, rooted in long-established rural traditions, that is now disappearing due to the rise of an urban consumerist.

Jon Anderson

Caña brava is the finest cane, the sweetest, and the toughest to extract. Its roots run deep. Its stalk repels the blow of the machete. Brava connotes ferocity, anger, heated aggression—qualities that define the malevolent environment in which the cane cutters find themselves; for cane is their implacable foe, and the plantations their perdition. Many thousands have died on the plantations. After the Taino Indians were worked to extinction, the Spaniards brought in African slaves from the Congo; and long after that, when Americans revived the plantation system, the gringo “misters” brought in the Haitians, who to this day comprise the majority of cane cutters. As a Chinese proverb says, no cane is sweet at both ends, and while we in the United States continue to savor our imported sugar, those who cut it, crush it, extract and boil its sap, taste nothing but bitterness.

The bateys, a Taino word for their villages—later appropriated to designate plantation housing—can be anything from a cluster of tumble down shacks to a more systematic arrangement of bachelor barracks. In recent years, they have become housing for the landless rural poor, and Dominicans and Haitians mingled together there. Living in almost complete isolation, they lack basic things Americans take for granted, including legal rights; they are essentially stateless. Even those born on Dominican soil are denied a cedula, an identity card, and without the cedula they are ipso facto without identity. They are simply braceros, men who live by the strength of their arm (brazo).

The braceros today are in limbo, caught between the demise of the old sugar economy and the new tourist-driven economy that now buoys the Dominican Republic. The cruelest irony of all is that while it was bad enough under the old dispensation, it is worse still in an era of economic progress. The plantation system has fallen into neglect; sugar factories are in disrepair or shut down. There are many bateys, lost amid forests of wild cane, where the people are starving for lack of work.

The photographs here, culled from two years of shooting, lay bare the plight of these people, but more importantly they celebrate a way of life born out of adversity, which has historically formed an essential strand of Dominican life as a whole. They serve as a reminder, not just of the strength and humanity of these people, but of the fact that Haitians and Dominicans share more than geography and history: they share a vital culture. In the face of this connection, the ethnic and linguistic differences that have so long divided the island disappear.

—Jon Anderson, April 2002