20151021-kouris-mw23-collection-001

Sofian, a migrant from Algeria, sits inside the deserted Columbia Records building. Sofian lived in the building for six months, eventually returning to his homeland after his efforts to reach France were unsuccessful.

Athens, Greece, September 2010

20151021-kouris-mw23-collection-002

Khalifa shaves in the mirror at the deserted Columbia Records building.

Athens, Greece, September 2010

20151021-kouris-mw23-collection-003

A makeshift room at the deserted Columbia Records building.

Athens, Greece, January 2012

20151021-kouris-mw23-collection-004

An Algerian man sleeps in a shared space at the deserted Columbia Records building.

Athens, Greece, October 2012

20151021-kouris-mw23-collection-005

A man washes clothes at the deserted Columbia Records building with water collected from a nearby park.

Athens, Greece, September 2010

20151021-kouris-mw23-collection-006

Mohamed reads the Koran during Ramadan. He had hung a Greek flag in the window in hopes of curbing the racist attacks that had surged against those in the building.

Athens, Greece, September 2010

20151021-kouris-mw23-collection-007

A group of Algerian men share lunch together. They are all undocumented migrants.

Athens, Greece, October 2012

20151021-kouris-mw23-collection-008

Still image from In Transit: Columbia Records, Athens, 2015

Running time: 5 minutes

Using footage taken inside the deserted Columbia Records building, Kouris presents what daily life is like for a group of Algerian men living in limbo between North Africa and Europe.

Dionysis Kouris (Greek, b. 1968) earned a degree in photography from the Arts University of Bournemouth, United Kingdom, in 1992 and worked in Greece for more than 10 years as a studio and editorial photographer. In 2006, after he took part in a one-week workshop with Gary Knight from VII Photo, Kouris transitioned to social documentary photography. In 2010, he completed his photographic studies at the London College of Communication, receiving an MA in photojournalism and documentary photography.

Kouris was selected for the Eddie Adams Workshop in 2010 and produced a multimedia story, “Road to the Future,” with Brian Storm. His work has been recognized in the PDN Photo Annual competition in 2011 and 2012, and received Honorable Mention in the Poznań Photo Diploma Award competition at the 2011 Biennale of Photography in Poznań, Poland. Since 2008, Kouris’s focus has increasingly turned to immigration and the consequences of the financial crisis in Europe.

Dionysis Kouris

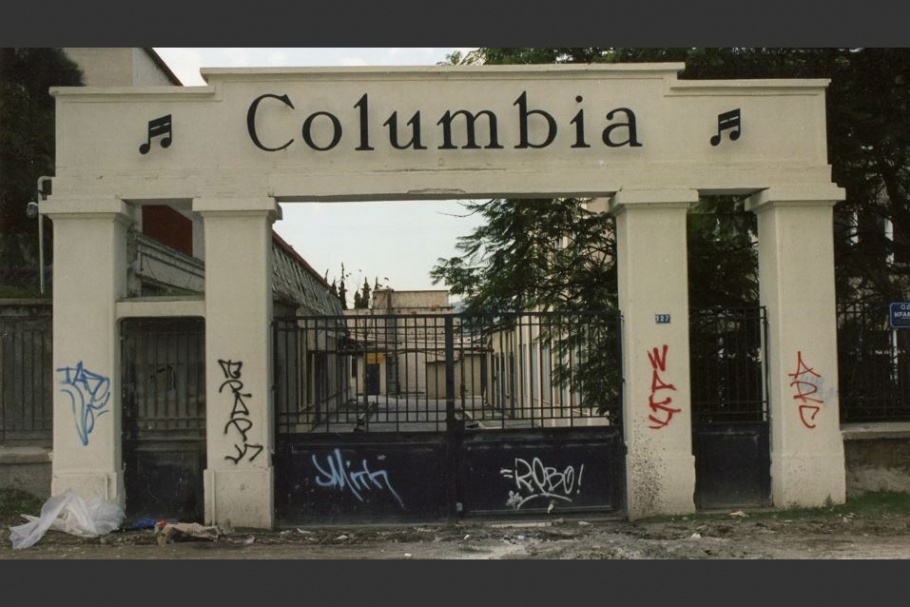

In the early 1930s, Columbia Records, under the recording and publishing company EMI, was the first record label to open a studio and factory in Greece. Due in part to the demand for exports to the Middle East, the factory enjoyed success from the 1950s to the 1980s. The factory closed down in 1991, and starting around 2009, the record company’s deserted building was frequently occupied by migrant squatters.

“We are Palestinians. All the people here come from Palestine,” one of the squatters named Aissa told me. Of the 60 to 70 North Africans, mostly from Algeria, who I photographed at the factory from 2010 to 2012, all of them had told the police their country of origin was Palestine, and they had received papers from the police indicating this. Their hope was that if they were identified as Palestinians, they would have a greater chance of obtaining asylum as refugees instead of being classified as economic migrants, who have fewer chances of acquiring legal papers. In fact, in many cases the distinction between asylum seekers, refugees, and economic migrants is confusing and not easy to untangle.

Due to a dearth of jobs in Greece, nearly all of the migrants I met wanted to continue on to France or another large, wealthy European country. Some would try their luck at the port of Patras, hiding in containers and trucks in hopes of boarding a ship to Italy. Others managed to buy a fake passport or identity card and attempted to travel by plane to different European destinations.

Today, in 2015, Greece has newly emerged as a country receiving large numbers of immigrants. Its geographical position makes it a gatekeeper to the European Union. There are very few legal entry paths, and almost all migrants arrive illegally. Conflict and political upheaval in North Africa and Syria have prompted a surge of immigrants. Meanwhile, Greece is undergoing its worst economic crisis, adding complexity to the Greek government’s inability to cope with the influx of migrants.

Using the abandoned music factory as a central focus, my aim for this story is to explore how factors—such as xenophobia, the rise of far-right parties, and racist attacks—that often drive people away from a country are occurring in the very place that is now drawing people in.

—Dionysis Kouris, October 2015