20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-001

Farida Ado Gaci, 27, a romance novelist living in Northern Nigeria, at her window. She is one of a small but significant group of Nigerian women authors of books called littattafan soyayya, Hausa for “love literature.”

Kano Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-002

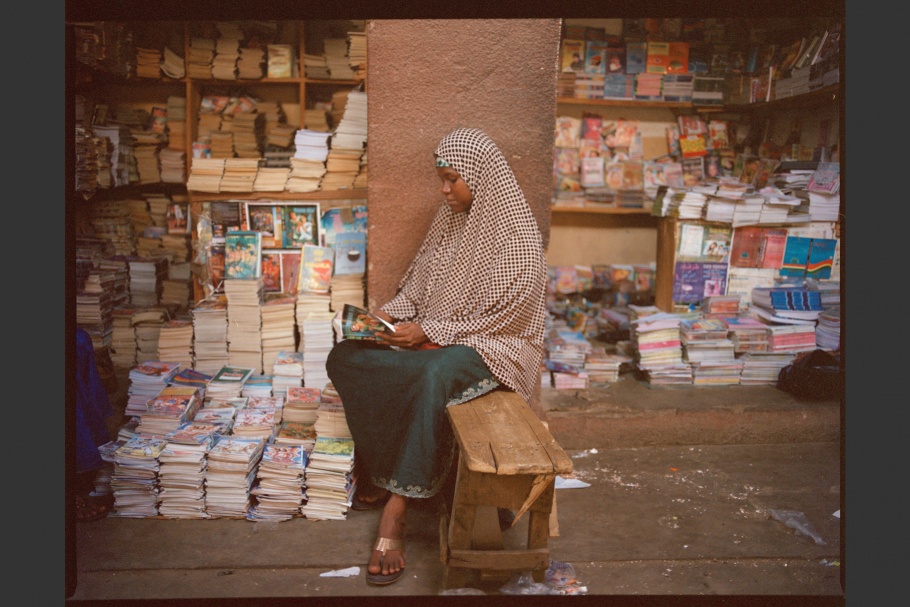

Fauziyya D. Sulaiman, a romance novelist, reads a book at the market after dropping off her newest release for sale. Littattafan soyayya books are printed cheaply and quickly, and sold for about 50–100 naira, or less than one U.S. dollar.

Kano, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-003

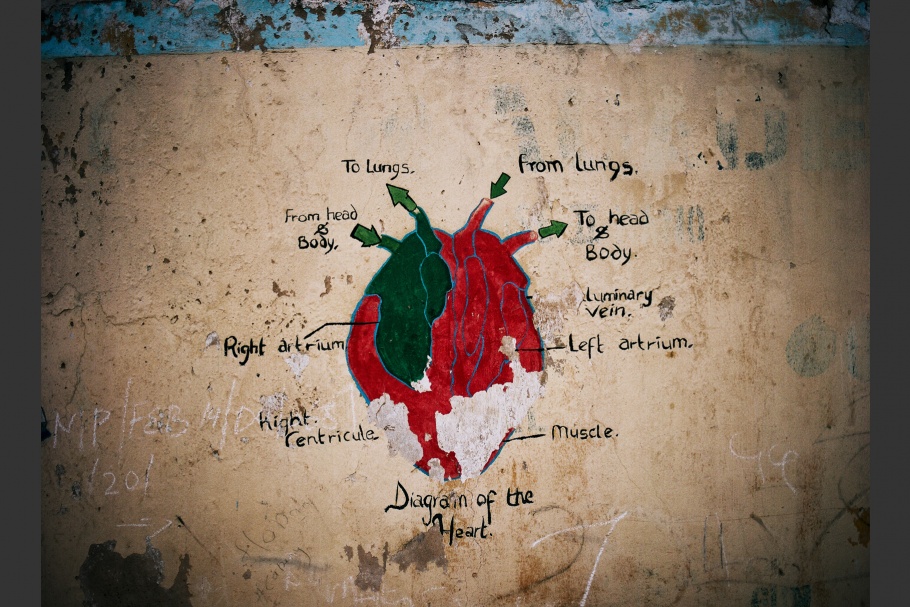

Graffiti outside a school shows a diagram of the heart.

Kano, Nigeria, February 2014

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-004

A bride walks through a corridor connecting two homes. Many houses in Kano are constructed with several rooms leading into a shared open space, and corridors connect one home to the next, especially in the old city.

Kano, Nigeria, September 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-005

Hadiza Sani Garba works on her novel while lying in bed at home. Most authors write their novels by hand in composition books. Afterwards, they are typed, mimeographed, assembled by hand, and published.

Kano, Nigeria, September 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-006

A bride sits with her mother on her wedding day.

Dawakin Tofa, Nigeria, November 2014

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-007

A bride at her wedding.

Kano, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-008

Rabi’a Talle Maifata, a romance novelist, walks in the courtyard of her office at the Ministry of Information.

Kano, Nigeria, February 2014

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-009

Lubabatu Ya’h is a popular writer who also produces Hausa films.

Kano, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-010

Sa’adatu Baba Ahmad Fagge has written many novels and also reviews them in local newspapers.

Abuja, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-011

Balaraba Ramat Yakubu was the first woman to write a Hausa littattafan soyayya novel. She often writes about forced marriage and other issues affecting women.

Kano, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-012

Baidau Muhammed Gaba has written 15 novels. She is uninterested in jobs that would require her to work outside of her house, and luckily writing allows her to work at home.

Kaduna, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-013

Umma R. Homhammed writes every day for about six hours, and it takes her about two months to finish most of her books. Her novels are often about love, and the challenges her characters face related to tribalism and co-wives.

Kaduna, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-014

Rabi’a Talle Maifata’s next novel will be called Victim of Love.

Kano, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-015

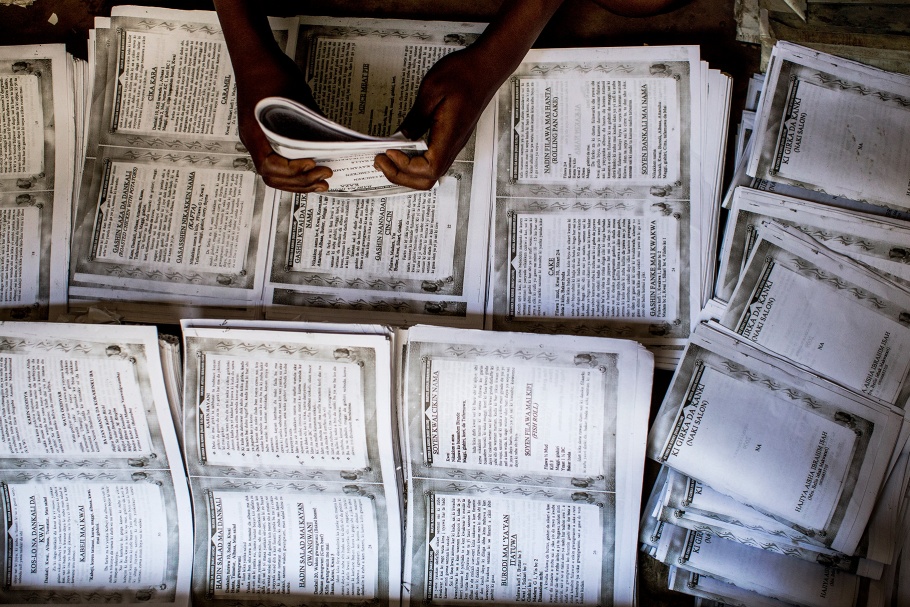

Newly printed pages of books are bound by hand.

Kano, Nigeria, April 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-016

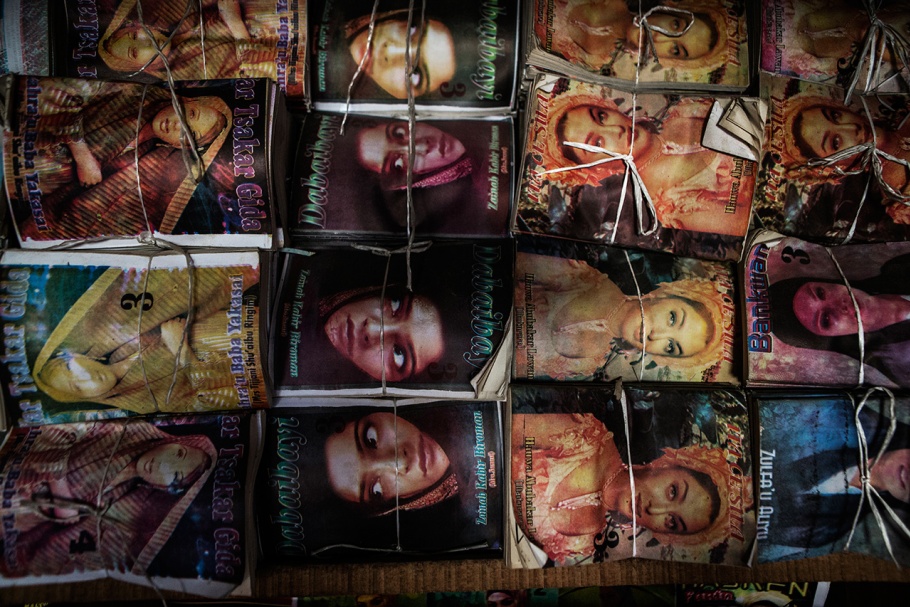

Books are tied and packaged at the local market.

Kano, Nigeria, October 2013

20151021-gordon-mw23-collection-017

Jamila Umar Tanko, a popular writer, stands inside the bookshop that she runs. She opened her own shop at the market after she was tired of not getting paid fairly for her book sales by the other men running shops in the market.

Kano, Nigeria, October 2013

Glenna Gordon (American, b. 1981) is a documentary photographer and photojournalist working often in West Africa and elsewhere on the continent. Her work has covered topics ranging from Nigerian weddings, traces left behind by the 300 schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram, released Western hostages kidnapped by ISIS and al-Qaeda, and Muslim women romance novelists in the Sahel region.

In addition to winning a World Press Photo award in 2015, Gordon’s work has received many honors including from the LensCulture Visual Storytelling Awards (2014), the PDN Photo Annual competition (2013), and the PX3 Prix de la Photographie Paris (2014).

Gordon has been commissioned by Le Monde, the New York Times, Time magazine, and the Wall Street Journal, and her images have been included in group shows in London, New York, Nigeria, and Washington, D.C. Gordon is an adjunct professor at The New School in New York.

Glenna Gordon

Rabi’a Talle Maifata is one of several dozen popular romance novelists living in the predominantly Muslim northern city of Kano, Nigeria’s second biggest city. She is one of a small but significant group of women in Northern Nigeria writing books called littattafan soyayya, meaning “love literature” in the Hausa language.

Read by women and girls in Northern Nigeria and across the Sahel region, these stories are somewhere in between morality tales and romance novels. Small publishers print thousands of copies of the stories, and the books are sold in markets and streets for a dollar or two each.

Littattafan soyayya writers, who are all devout Muslims, must face off with Islamic censors who make them register with the Hisbah, a morality police, as well as government officials, such as a minister of education who publicly burned many books in 2007. These novels range in tone from subversive and disruptive of the norm—speaking out against child marriage and human trafficking—to those that yield to the status quo, advising women on how best to please their husbands and offering fantasies of escape and tales of the poor girl marrying the rich man.

Northern Nigeria made headlines in 2014 when the Islamic terrorist group Boko Haram—the name translates to “Western education is sinful”—kidnapped nearly 300 schoolgirls from a remote dormitory. Tens of thousands of people have died since 2009 due to the insurgency led by Boko Haram separatists and the Nigerian army’s escalating response.

While I covered this and other stories as a photojournalist, the authors and their books enabled me to photograph without the constraints of a predetermined narrative or media cycle. Guided by the themes of the novels, my aim is to explore romance, tradition, love, and loss in Northern Nigeria.

—Glenna Gordon, October 2015