20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-001

“I feel like a mermaid. My body tells me I am a man, and my soul tells me I am a woman.”

—Heena, 51

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-002

Untitled

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-003

Rumi, 39, gave him all, even beyond her body. But the fact remains, her boyfriend could only return a mere liking. Love is a much higher commodity.

Kolkata, India, 2014

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-004

“Always desiring to be a mother, I have adopted Boishakhi. But I wonder, what if she calls me father someday!”

—Salma, 27

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-005

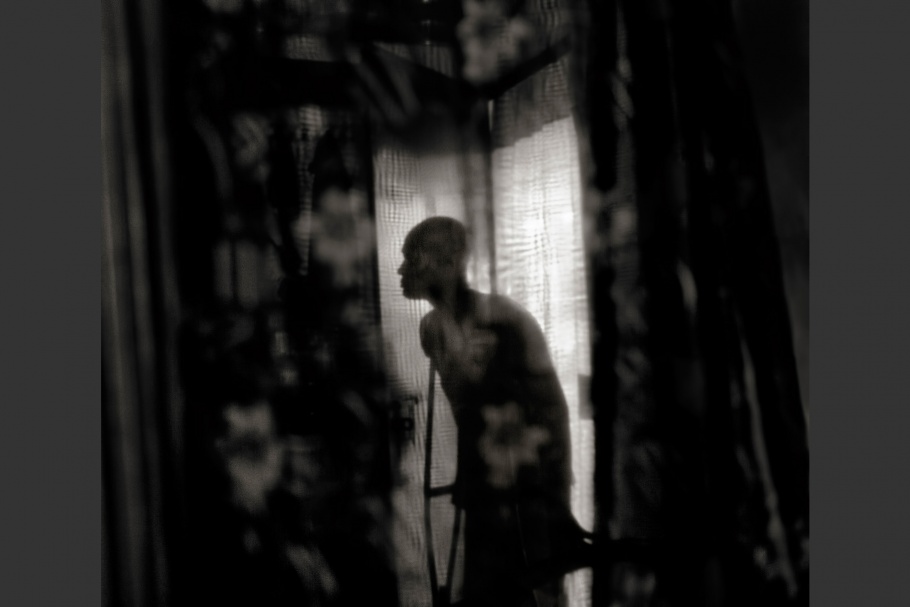

Untitled

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-006

Poppy, 47, and Kesri, 45, may not be accepted by their families, whom they left ages ago, but they find strength in each other and have lived together for decades. They have forged a friendship that comes close to fulfilling their desire for unconditional love.

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-007

“I am taking an exam; the result is unknown to me.”

—Tina, 21

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-008

Riya, 29, has daily afternoon conversations with death. She has lost one of her legs to her battle with cancer.

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-009

After the end of Natasha’s 15-year relationship, she gave up on love. She is in a relationship now with herself, playing the part of a man and a woman. This duality promises fulfillment without heartbreak.

Delhi, India, 2014

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-010

Untitled

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-011

At dawn, Nayan, 24, goes to work at a garment factory and earns what’s perceived as honest income by her family. But at dusk she returns to her community.

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-012

Both ostracized from their families, Shumi and Priya forge a new life that is bound by the rules of a guru—a leader in the informal market for whom they work and perform as entertainers in order to earn money—in exchange for an accepting home and community.

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-013

Moyna, 54, had a guru who passed away, leaving her a widow with the responsibilities and restrictions of the real world. It’s been 40 years since Moyna went home, but between the puffs of her smoking pipe she dreams for a death in her motherland: Bangladesh.

Kolkata, India, 2014

20151021-sharmin-mw23-collection-014

When Mohona, 29, turned 10 years old, her father locked her up for three years to hide her feminine nature from the world. After breaking free and eloping, she eventually ended up in Delhi. She feels she can live more freely now, but it cost her a place within her family home in Bangladesh.

Delhi, India, 2014

After completing her studies in public administration at the University of Dhaka, Shahria Sharmin (Bangladeshi, b. 1972) discovered photography’s potential for storytelling and exploring the human experience. She pursued further study at Pathshala South Asian Media Academy in Bangladesh and received a photography degree in 2014.

Sharmin has received several prizes, including for the Moscow International Foto Award’s Lifestyle category (2014), and the Pride Photo Award’s Getting Closer category (2014). She was also named the second-place winner of the Alexia Foundation student grant (2014) for her project, Call Me Heena.

In 2014, Sharmin’s work was exhibited at the FotoVisura Spotlight Exhibition (Brisbane, Australia), the Internazionale d'Arte LGBTE (Turin, Italy), the Lightseekers & Asian Women Photographers' Showcase (Leicester, United Kingdom), the Obscura Festival (Penang, Malayasia), the Photissima Art Fair (Torino, Italy), and the Pride Photo Award exhibition (Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Sharmin was also selected as a finalist for the 2015 Renaissance Photography Prize, and her work will be exhibited in the Getty Images Gallery in London.

Shahria Sharmin

“I feel like a mermaid. My body tells me I am a man and my soul tells me I am a woman.”

—Heena (age 51)

Hijra is a South Asian term with no exact match in the English language. Hijras are people designated male or intersex at birth who adopt a feminine gender identity. Often mislabeled as hermaphrodites, eunuchs, or transsexuals in literature, hijras can be considered to fall under the umbrella term transgender, but many prefer the term third gender. Transcending a biological definition, hijras are more a social phenomenon, as a minority group having a long-recorded history in South Asia.

Hijras are believed to be associated with the Hindu goddess of fertility. Traditionally, hijras held semi sacred status and were hired to sing, dance, and bless newly married couples or newborns at household parties. Earnings were pooled through the guru system, in which hijras declare allegiance to an individual teacher or guide and submit to group rules, in exchange for financial and social security.

Although the guru system still exists, and the practice of hiring hijras for blessings continues in some communities, over time hijras have lost their admired and often sacred position in society. Now, many are shunned from schools and temples, are frequently denied health care and access to legal services, and often must work in the informal sector. Today, hijras’ overall social acceptance varies significantly in countries like Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

Growing up in Bangladesh, I was influenced by predominant prejudices and stereotypes about hijras. Then, I met Heena, who opened her life to me and helped me get to know the other members of her community as the mothers, daughters, friends, and lovers that they are. Call Me Heena is my attempt to show the beauty in hijra lives, despite the challenges and discrimination they face.

The project features hijras in Bangladesh, as well as a number of hijras who migrated to India. While hijras continue to face discrimination once in India, some have found greater social acceptance than in Bangladesh. At the same time, many Hijras in Bangladesh and other South Asian countries have stood up for their rights and gained at least limited legal recognition for a third gender. I hope my work will help amplify hijra voices that are largely quieted, and inspire hijras to open even more space for themselves within Bangladeshi society.

—Shahria Sharmin, October 2015