20141104-elahi-mw22-collection-001

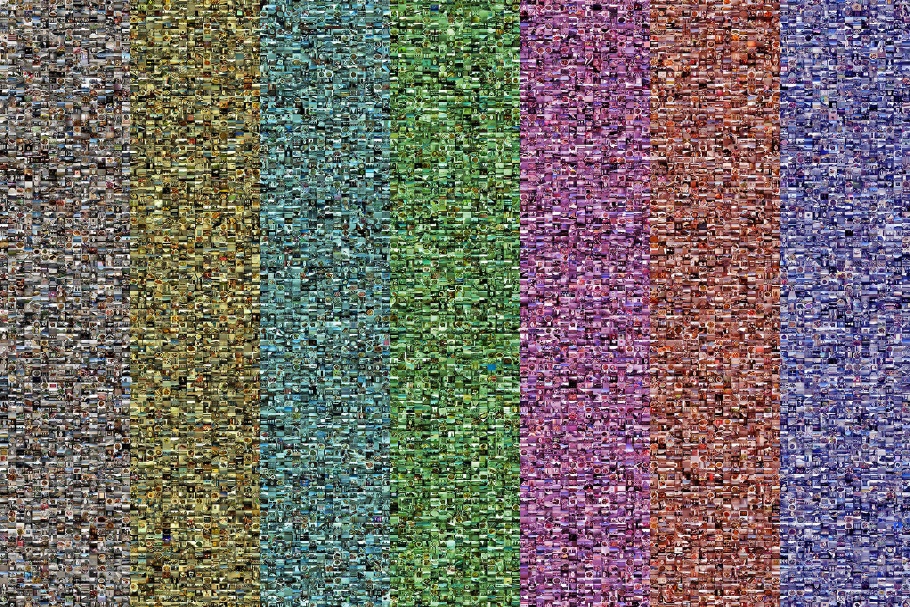

Detail from Thousand Little Brothers, 2014.

After an erroneous tip linking the artist to terrorist activities led to a six-month-long FBI investigation, Hasan Elahi began to voluntarily monitor himself by photographing mundane details from his daily life and sending these images—hundreds of them each week for over a dozen years—to the FBI.

This image is a detail from a composite image made up of approximately 32,000 images from that ongoing project. The colored panels refer to SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) color bars. This television test pattern has been used in the United States for Emergency Broadcast System tests, during which regular programming would be disrupted and this pattern would appear.

20141104-elahi-mw22-collection-002

Detail from Thousand Little Brothers, 2014.

After an erroneous tip linking the artist to terrorist activities led to a six-month-long FBI investigation, Hasan Elahi began to voluntarily monitor himself by photographing mundane details from his daily life and sending these images—hundreds of them each week for over a dozen years—to the FBI.

This image is a detail from a composite image made up of approximately 32,000 images from that ongoing project.

Hasan Elahi (American, b. 1972) is an interdisciplinary artist working with issues in surveillance, privacy, migration, citizenship, technology, and the challenges of borders. In an era where many of our daily activities are tracked and archived, his work represents a call to protect our own privacy by taking control of our personal data and creating our own digital noise.

Elahi’s work has been presented in numerous exhibitions at venues such as Centre Georges Pompidou, SITE Santa Fe, the Sundance Film Festival, and the Venice Biennale. His awards include grants from Art Matters Foundation, Creative Capital Foundation, and a Ford Foundation/Phillip Morris National Fellowship. Currently, he is an associate professor of art at the University of Maryland and lives outside of Washington, D.C., roughly equidistant from the headquarters of the CIA, the FBI, and the NSA.

Hasan Elahi

After an erroneous tip linking me to terrorist activities led to a six-month long FBI investigation, I decided to give the FBI a helping hand by sending them my itinerary whenever I traveled and turning my camera phone into a tracking device. Although multiple polygraph tests and interviews eventually cleared me, I wanted to make sure that the bureau knew that I wasn’t making any sudden moves, and inform them of what I was doing at any given time. My approach was: “OK, you want to watch me? That’s perfectly fine, but I can watch myself better than you guys ever can.”

As I monitored myself, I started thinking about what else the FBI might know about me. During the investigation, I told them every detail of my life. But were they really paying full attention? I wanted to make sure we both had the same information. So, I created my own parallel file and sent the FBI visual evidence documenting everything I did and when I did it. Over a decade later, I continue to voluntarily monitor myself and conduct this self-surveillance project.

Currently, I have sent nearly 70,000 images, and I trust that the FBI has seen them all. Similar to the detailed files kept by the Stasi security agency in the former German Democratic Republic, the FBI has access to records that track the stores I’ve shopped in: where I’ve bought my minced crab paste, my kimchi, or my laundry detergent. But unlike the Stasi, the FBI knows all of this because I’ve shown them everything. They have seen the airports I’ve transited through, the food I’ve eaten at home and on the road, the hotel beds I’ve slept in, and every toilet I’ve ever used.

By disclosing mundane details about my daily life, I am simultaneously telling everything and nothing about my life. I am flooding the market with banal information, and questioning its inherent meaning and value for intelligence purposes. As we generate and archive more data than ever before through digital tools and social media, we need to examine the perpetual surveillance that we direct at ourselves and that is directed at us by others, and consider the efficiency of both information gathering and information analysis within this context.

—Hasan Elahi, November 2014