20141104-menner-mw22-collection-001

Untitled, 2013.

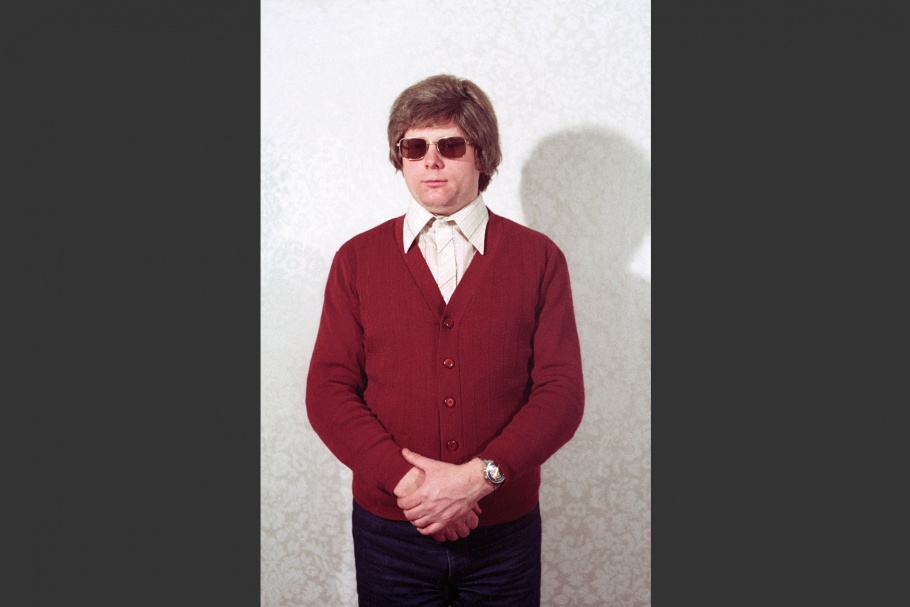

Stasi agent during a seminar on disguises.

This picture was originally taken during a seminar in which Stasi personnel were taught how to don different disguises. The goal of the seminar was to enable Stasi agents to move about in society as inconspicuously as possible.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-002

Untitled, 2013.

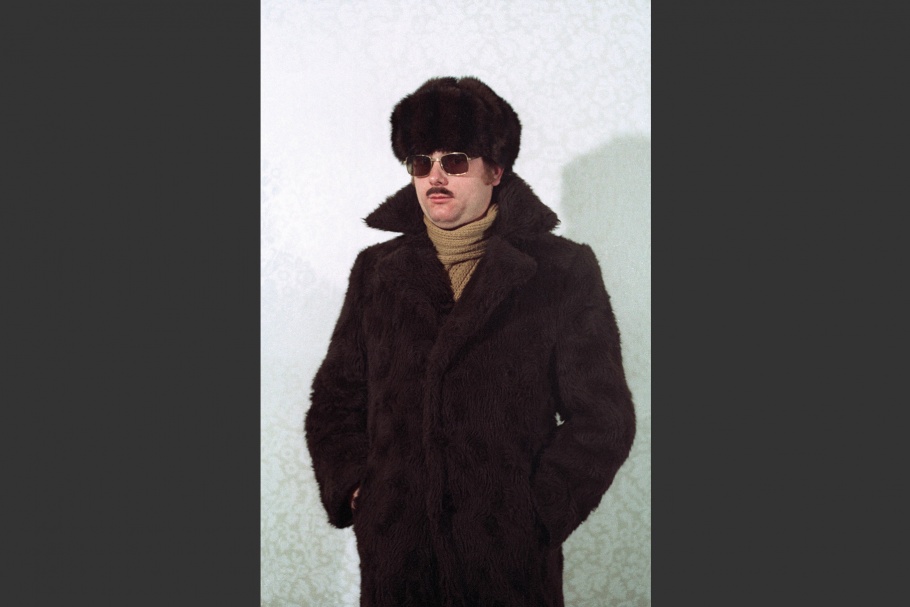

Stasi agent during a seminar on disguises.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-003

Untitled, 2013.

Stasi agent during a seminar on disguises.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-004

Untitled, 2013.

Stasi agent transmitting secret hand signals.

Prospective Stasi agents were taught how to convey secret signs in this seminar. It is no longer known what the individual signs mean.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-005

Detail from Untitled, 2013.

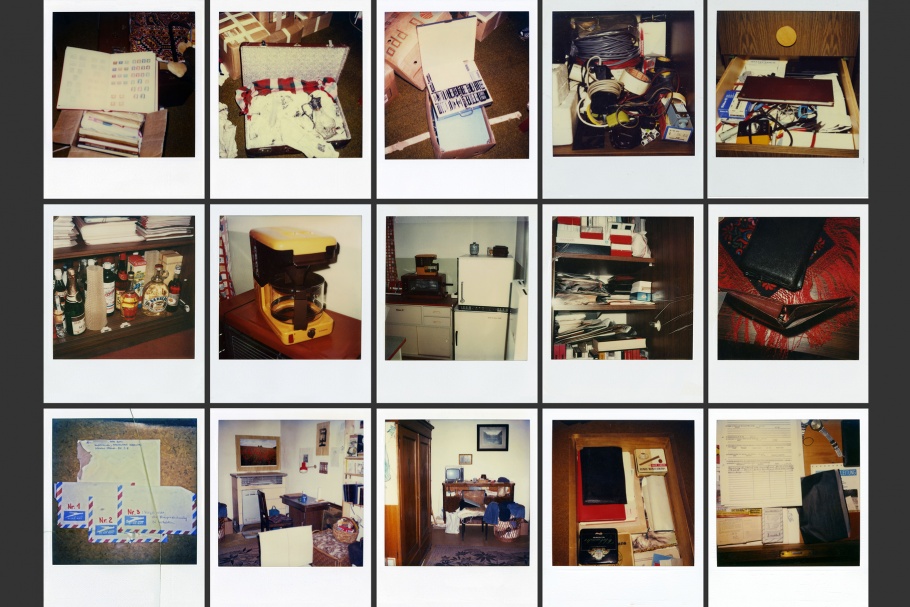

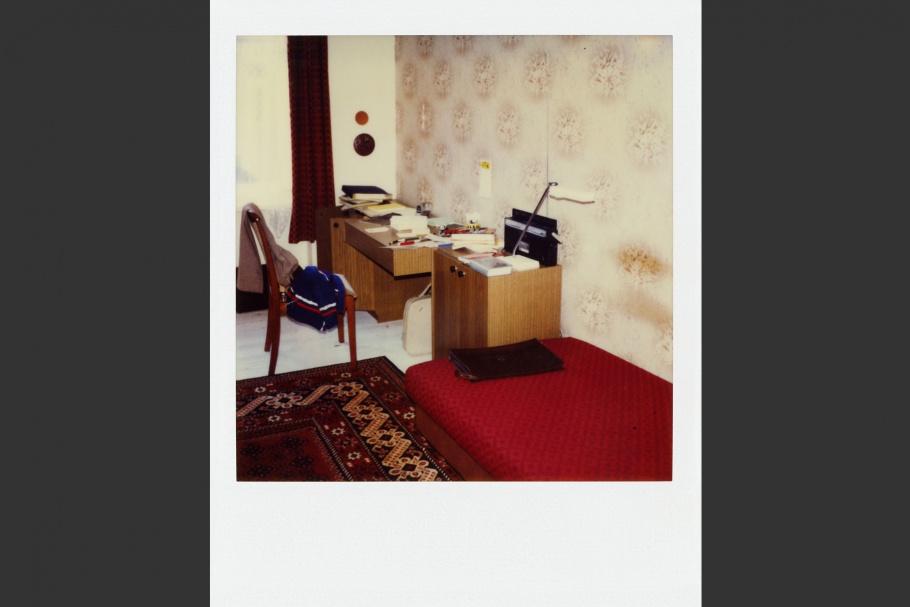

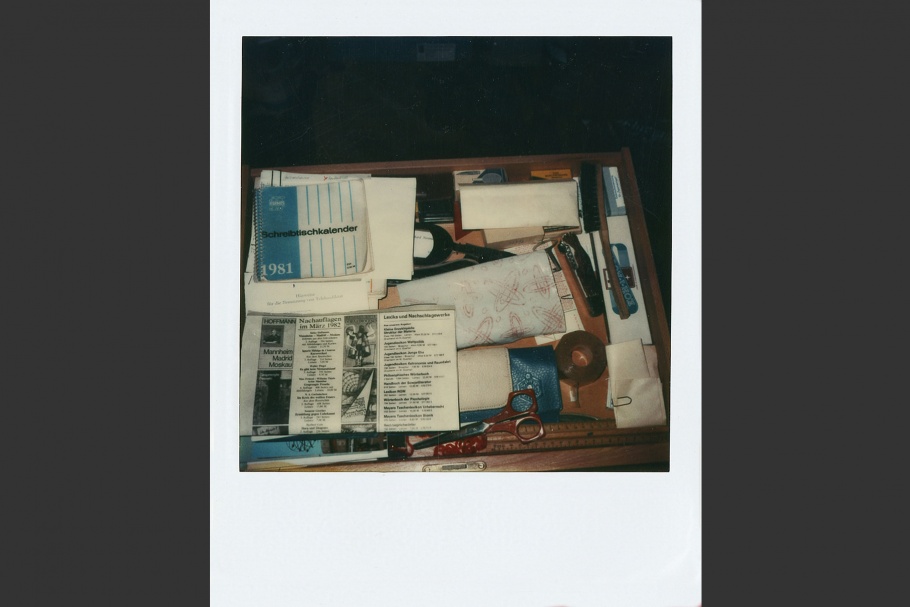

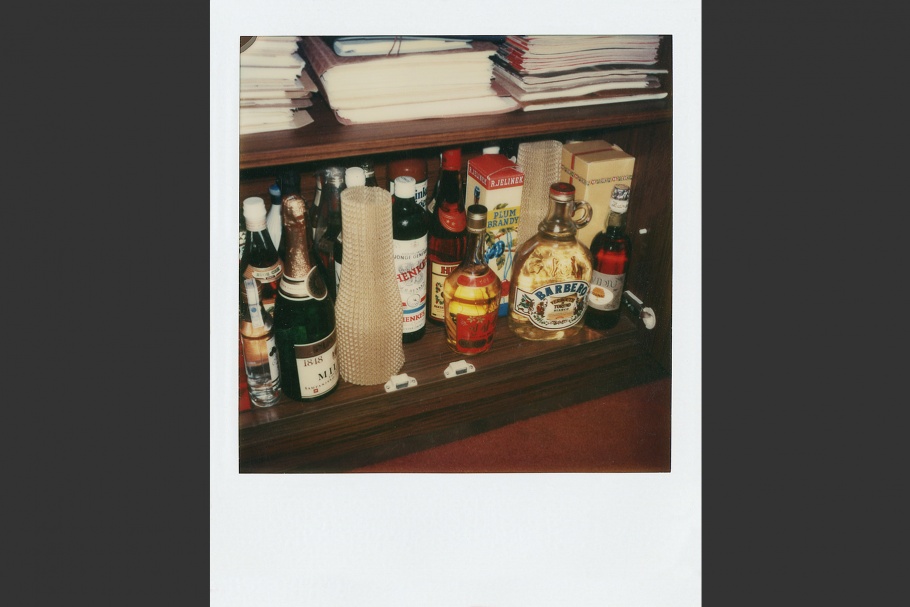

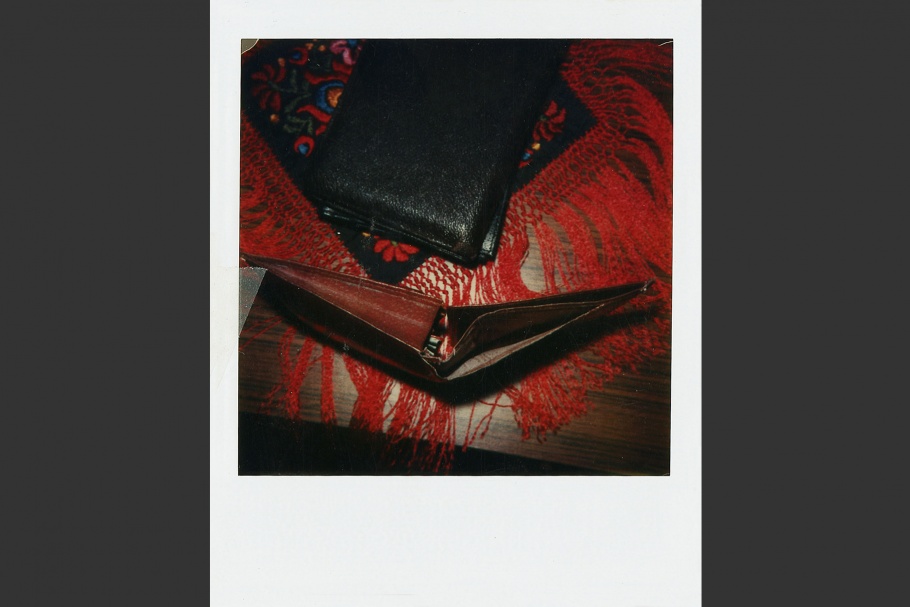

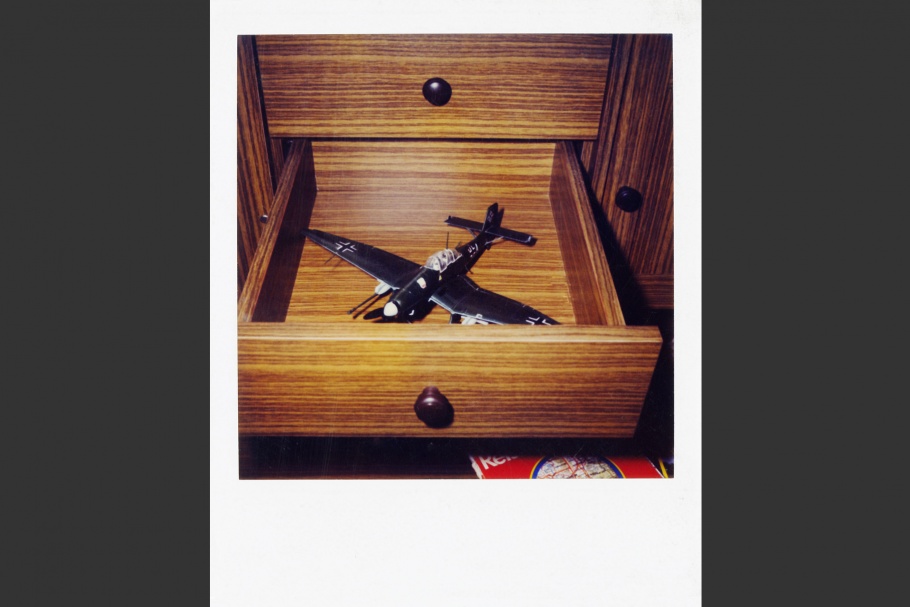

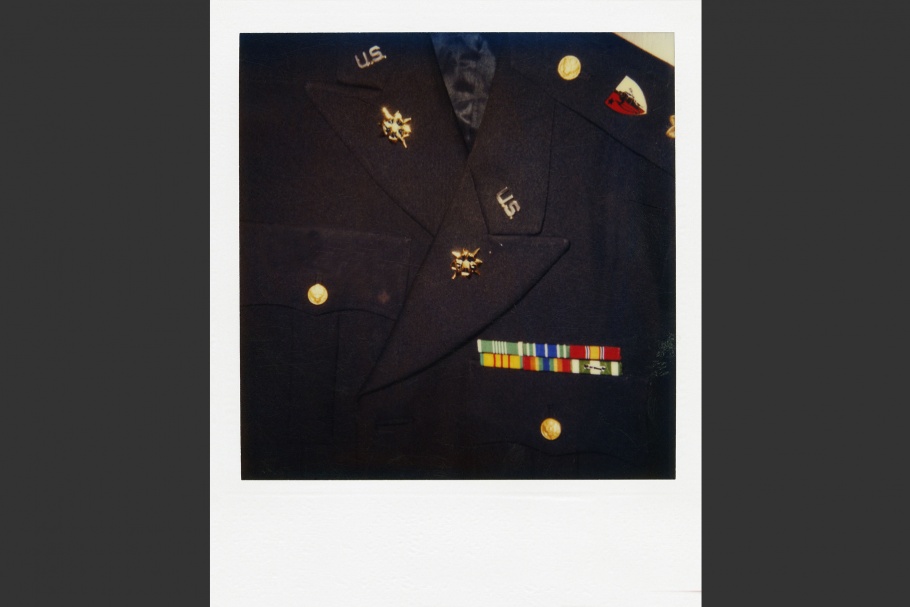

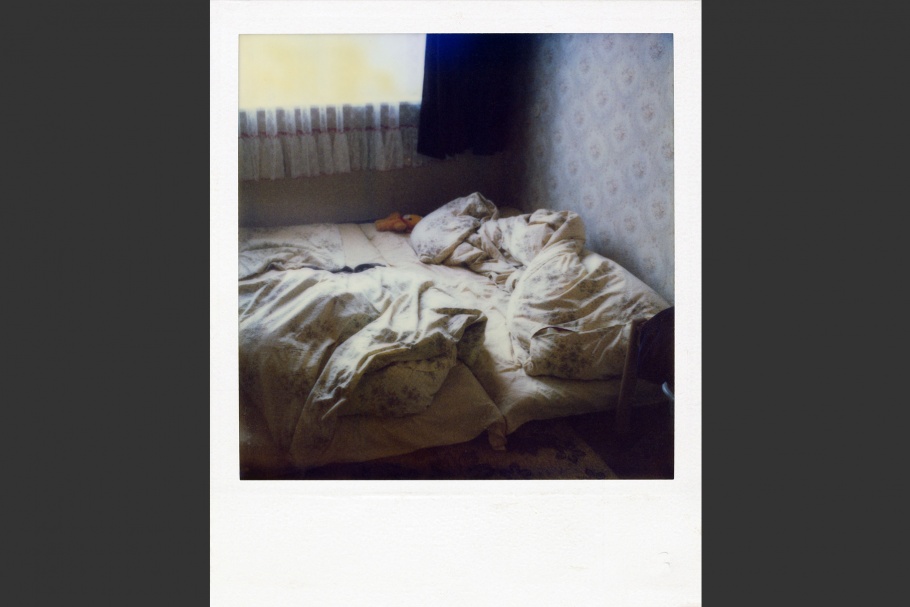

Installation of 100 Polaroids used in secret house searches.

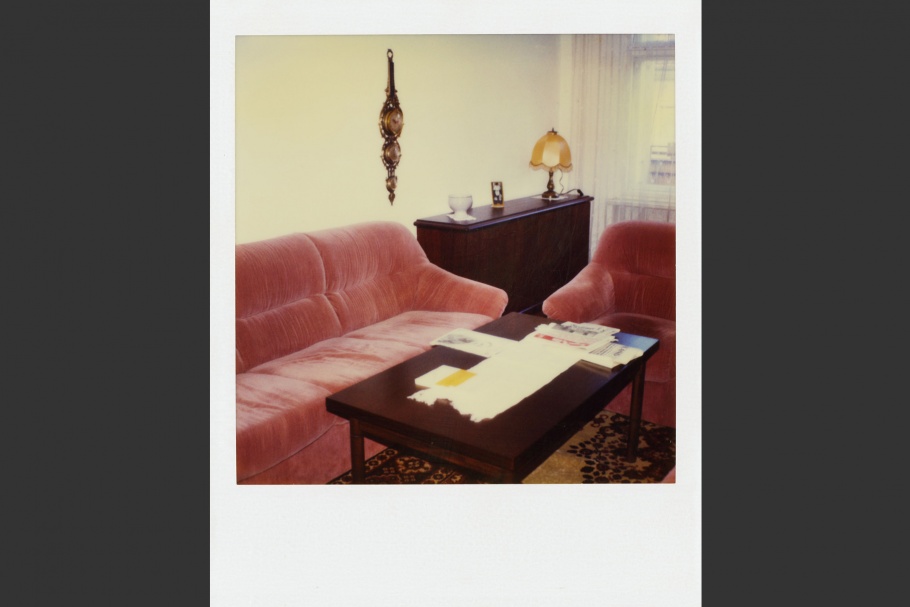

The Ministry for State Security often carried out secret house searches. Inhabitants were not informed about the searches—many first found out about these state-prescribed break-ins after German reunification—and they were deliberately left in the dark. Stasi agents used Polaroid cameras in order to carry out their search without leaving any traces. Before beginning their search, they took Polaroid pictures of suspicious parts of the house, enabling them to return everything to its original place afterwards. The picture of an unmade bed (see slideshow #15) is thus the picture of an unmade bed before it was searched.

The Polaroid film was bought in the West through covert channels and was often also confiscated along with various other types of film during the routine opening of private mail from the West.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-006

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-007

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-008

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-009

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-010

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-011

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-012

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-013

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-014

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-015

Untitled, 2013.

Polaroid used in a secret house search.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-016

Untitled, 2013.

Surveillance of mailboxes in Berlin.

When mailboxes were being observed by Stasi agents, every person posting a letter was photographed. Some films found in the Stasi archives also show persons dressed in civilian clothing emptying the mailbox after the conclusion of the surveillance action.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-017

Untitled, 2013.

Surveillance of mailboxes in Berlin.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-018

Untitled, 2013.

Surveillance of mailboxes in Berlin.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-019

Untitled, 2013.

Surveillance of mailboxes in Berlin.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-020

Untitled, 2013.

Surveillance of mailboxes in Berlin.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-021

Untitled, 2013.

Surveillance of mailboxes in Berlin.

20141104-menner-mw22-collection-022

Untitled, 2013.

A spy photographs a spy.

One of the Stasi’s main concerns was the surveillance of Western military liaison missions. Agents on both sides were very much aware of the presence of the other side. Spies of the Western allied forces photographed Stasi spies, and Stasi spies photographed their Western counterparts.

Simon Menner (German, b. 1978) has lived and worked in Berlin since 2000 and received a degree from the Universität der Künste in 2007.

As an artist, Menner is fascinated by how images and perception are utilized as tools of influence by government agencies, political players, and corporations. In our increasingly image-driven world, his work focuses on understanding and emphasizing mechanisms like propaganda, terror, and surveillance and, by doing so, enabling a public or personal response.

Menner has presented his work internationally at institutions such as the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and C/O Berlin.

Simon Menner

While conducting research on surveillance, I realized that the public has very limited access to images showing the act of surveillance from the perspective of the surveillant. What actually is it that the Orwellian “Big Brother” gets to see when he is watching us?

For over two and a half years, I applied this question to materials from the former East Germany’s Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the Stasi, which had become publicly available after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The Stasi was one of the most effective surveillance apparatuses ever. The quantity and breadth of the images I was able to unearth was surprising: images documenting Stasi agents being trained in hand signals, or perfecting the art of disguise; Polaroids taken during clandestine searches of people’s homes, to ensure everything could be put back where it belonged; photographs made by Stasi spies photographing other spies.

Many of the images shown here might appear absurd or even funny to us. But it is important not to lose sight of the original intentions behind these pictures—photographic records of the repression exerted by the state to subdue its own citizens. The banality of some of these pictures makes them even more repulsive. Many of the images are open to wide interpretation and could feed or confirm the suspicions of the Stasi agents viewing them. For example, the photograph of a Siemens coffeemaker: Is this West German consumer product evidence of contacts with Western agents? Or merely a present from relatives? The difference can mean years in prison, demonstrating one of the fundamental problems and limitations inherent to any and all forms of surveillance.

Presenting most of these pictures can be a double-edged sword. Many represent an undue intrusion into people’s private lives. Does reproducing them repeat the intrusion and renew injustices committed years ago? I grappled with this difficult issue and concluded that the pictures should be presented because they make an important contribution to discussions about state-sanctioned surveillance systems.

—Simon Menner, November 2014