20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-001

Agents working for Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi sat in an open plan room like this one in this six-story building in Tripoli, where they spied on emails and chat messages with the help of technology Libya acquired from the West.

Tripoli, Libya, August 30, 2011.

20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-002

A room in Libya's internet surveillance center.

Tripoli, Libya, August 30, 2011.

20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-003

An underground conference and meeting room at the Libyan government's intelligence headquarters.

Tripoli, Libya, August 31, 2011.

20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-004

A room in Libya's internet surveillance center.

Tripoli, Libya, August 30, 2011.

20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-005

White corridor in an abandoned security unit in Tripoli.

Tripoli, Libya, August 30, 2011.

20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-006

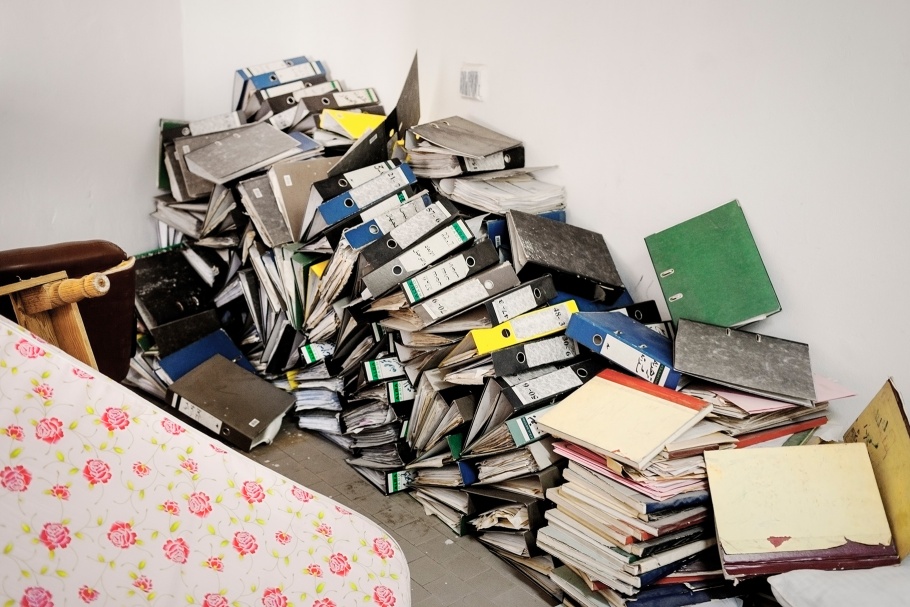

Old folders are piled up in a corner in Libya's internet surveillance center.

Tripoli, Libya, August 30, 2011.

20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-007

Libya's internet surveillance center.

Tripoli, Libya, August 30, 2011.

20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-008

Libya's internet surveillance center.

Tripoli, Libya, August 30, 2011.

20141104-bayer-mw22-collection-009

Office of Abdel Hamid Ammar Ouhaida (Assistant to the Administrative Director of Intelligence) in the Libyan government's intelligence headquarters.

Tripoli, Libya, August 31, 2011.

Edu Bayer (Catalan, b. 1982) is a photographer based in Barcelona. He graduated with a degree in chemical engineering from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. After a trip through South America, he enrolled in the Institut d'Estudis Fotogràfics de Catalunya, and later earned a master’s degree from the Danish School of Media and Journalism.

Since 2006, Bayer has worked in Spain for the newspapers, El País and Público. In addition, he has traveled extensively covering important events and stories in Burma, Gambia, Kosovo, Turkish and Iraqi Kurdistan, Libya, and Rwanda; and has published work in the Guardian, the Independent, Le Monde, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal.

Bayer is particularly interested in how different communities attempt to improve their current conditions by struggling to change political and economic systems. Bayer is currently working on a long-term transmedia project with writer Marc Serena about contemporary rural life in Catalonia.

Edu Bayer

This series of photographs depicts the surveillance apparatus of Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi’s regime—once one of the most feared authoritarian dictatorships in the world. The images encourage us to reflect on surveillance of citizens by state powers.

Qaddafi was a controversial figure. His supporters lauded his anti-imperialist stance, as well as his pan-Arabism and pan-Africanism, while his detractors saw him as an obsessive autocrat who systematically violated the human rights of Libyan citizens. The regime intentionally marginalized areas and suppressed efforts at democratic reform until the Arab Uprisings of 2011.

I went to Libya in early 2011 to cover the conflict; and like many journalists, I was attracted to the idea of revolution and wanted to witness the power of people collectively fighting to improve their lives.

In August, the Wall Street Journal assigned me to photograph Qaddafi’s internet surveillance center and intelligence headquarters in Tripoli, which had been abandoned by the regime. The surveillance center was a six-story building where the government monitored citizens’ movements and correspondence. By summer 2011, it had become the empty core of a repressive machine. It was an evocative scene, and I imagined what must have taken place there, the people involved, and the conversations they had.

My intention behind these images lies in the sense of chaos that is left behind, and freezing the moment just after the escape of the last occupants and before the arrival of the new residents. Many believe that the Libyan authorities destroyed the extremely sensitive files and information before they abandoned the building, and that the rebels removed the remaining documents when they arrived.

The photographs of this strange and usually off-limits place reflect the absurdity and ugliness of control, repression, and fear. They also serve as evidence that even the most powerful regime can be reduced to an empty building with shredded documents on the floor.

—Edu Bayer, November 2014