views-of-the-reservation-route18-mw19-collection

John Willis

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), Route 18, 2005.

views-of-the-reservation-teepees-mw19-collection

John Willis

A Nation In Distress, 2004.

A Lakota veteran’s protest to the treatment of Muslims after September 11, 2001.

views-of-the-reservation-security-shack-mw19-collection

John Willis

Security shack for a Sun Dance to keep out unwanted visitors, 2005.

views-of-the-reservation-flags-mw19-collection

John Willis

Veterans’ honor guard at the graduation powwow for Oglala Lakota College, 2005.

views-of-the-reservation-trampoline-mw19-collection

John Willis

Walmart trampoline, Potato Creek Housing, 2005.

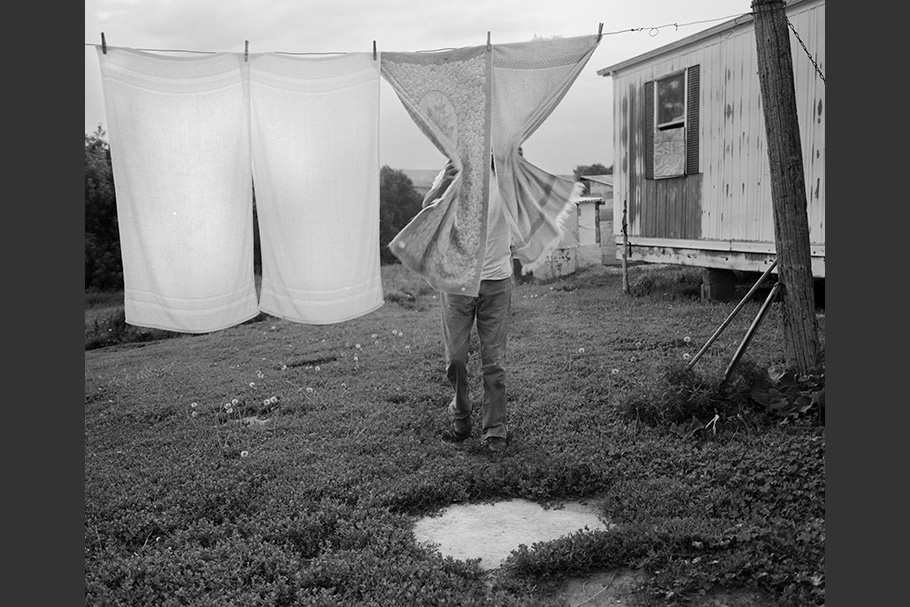

views-of-the-reservation-clothesline-mw19-collection

John Willis

Eugene checking the laundry, 2001.

views-of-the-reservation-pet-wolf-mw19-collection

John Willis

Vern Sitting Bear and his niece’s pet wolf, 2004.

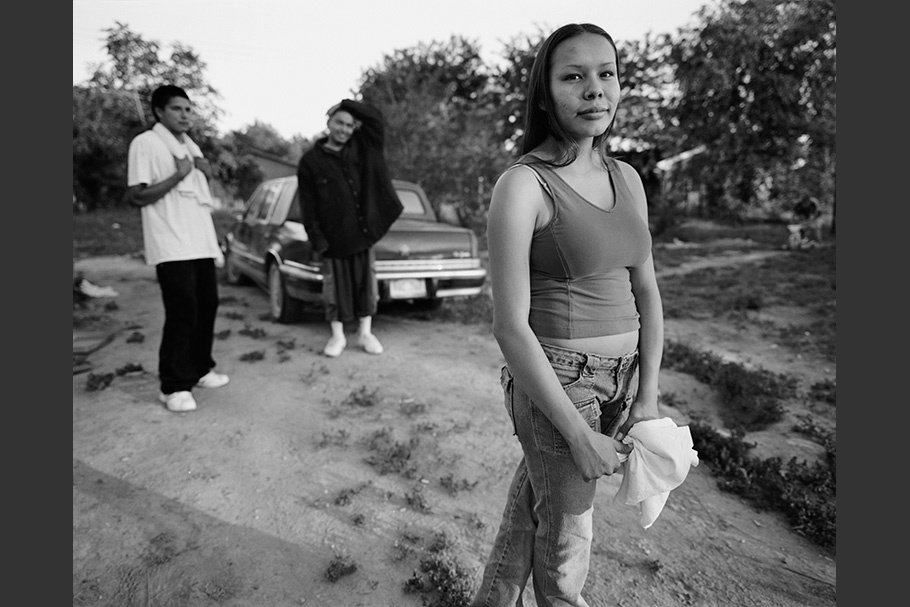

views-of-the-reservation-pine-ridge-mw19-collection

John Willis

Pine Ridge, 2004.

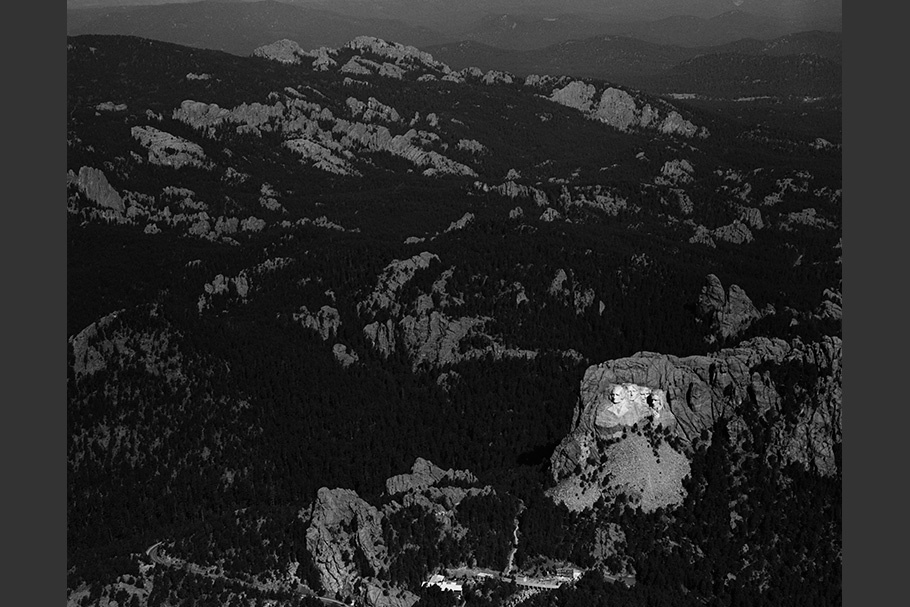

views-of-the-reservation-mount-rushmore-mw19-collection

John Willis

Mount Rushmore National Monument, where the faces of four U.S. Presidents are scarred into the sacred Paha Sapa (Black Hills), 2005.

views-of-the-reservation-mural-mw19-collection

John Willis

A New Deal mural. Pine Ridge High School, 2004.

This Work Projects Administration panoramic mural circled the walls of the auditorium in the Pine Ridge High School. This school is a community public school now but the mural was painted in the days when the government chose to send native youth to boarding schools throughout the country. The youth were shipped to reservations far enough away from their communities to facilitate the ban on wearing traditional clothes, speaking their language, or practicing their religion. Each school’s student body would consist of members from many tribes making it difficult for the youth to hold onto their culture, with the goal of assimilating them into mainstream society. Schools operated in this fashion into the 1970’s. In the summer of 2004, this mural was finally removed from the school, not because it was offensive, but rather to re-build a more structurally sound auditorium.

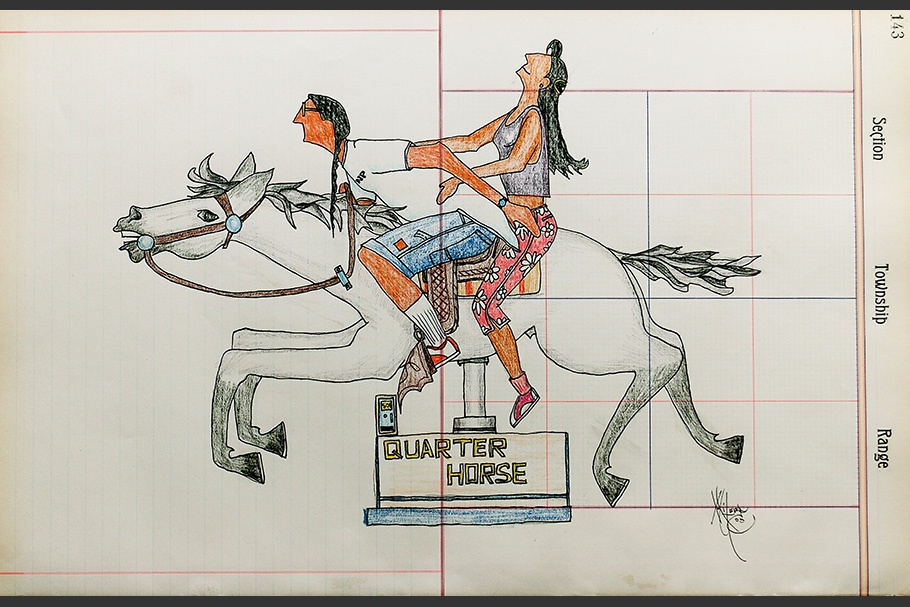

views-of-the-reservation-horse-mw19-collection

Dwayne Wilcox

Hang In There Baby, 2005.

Ink and colored pencil on 1893 ledger paper

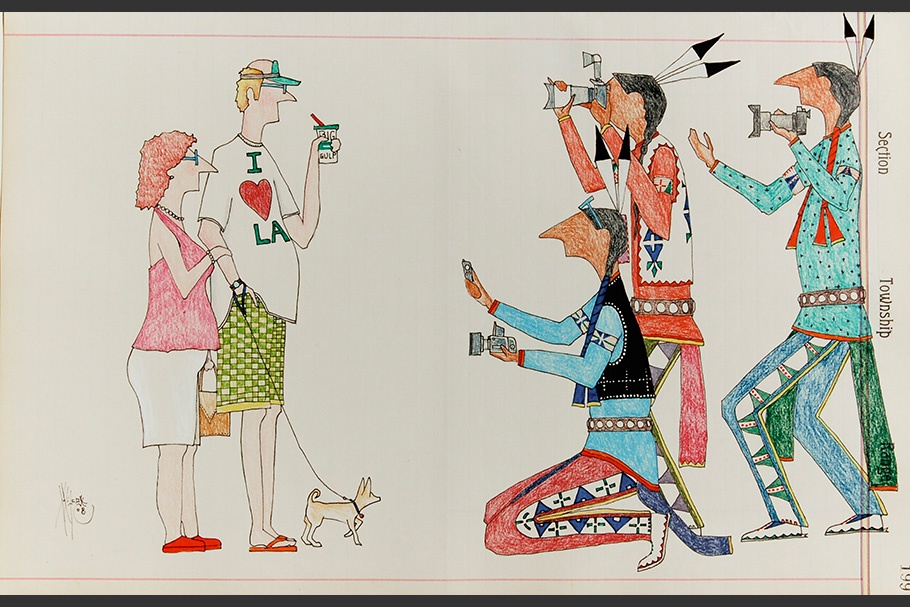

views-of-the-reservation-white-people-mw19-collection

Dwayne Wilcox

Wow Real Blooded White People, 2008.

Ink and colored pencil on 1893 ledger paper

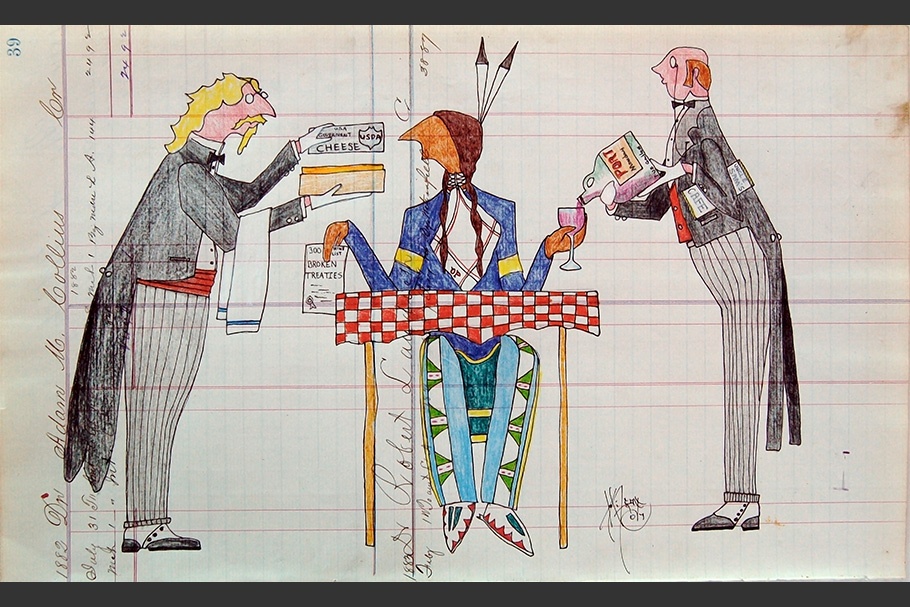

views-of-the-reservation-waiters-mw19-collection

Dwayne Wilcox

Cheese With That Whine, 2007.

Ink and colored pencil on 1882 ledger paper

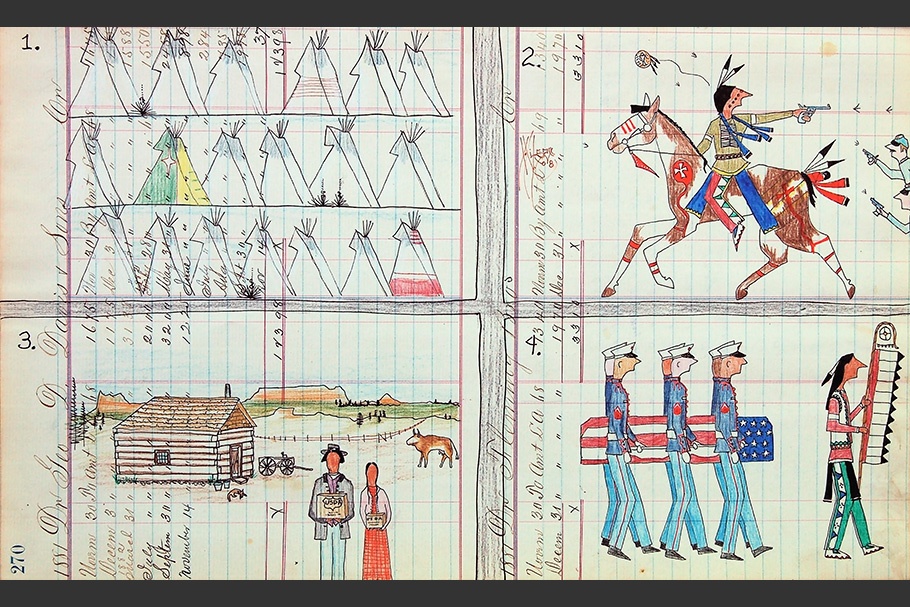

views-of-the-reservation-battle-mw19-collection

Dwayne Wilcox

From Here To Eternity, 2008.

Ink and colored pencil on 1881 ledger paper

views-of-the-reservation-quill-frame-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

A porcupine quill frame made by Ellen Hollow Head with a photograph of her great uncle, circa 1865.

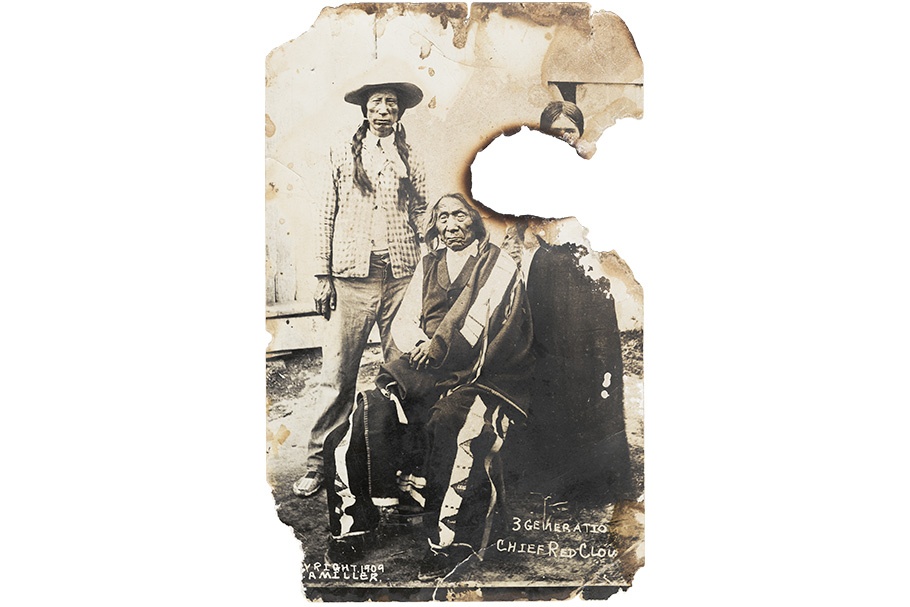

views-of-the-reservation-red-cloud-mw19-collection

J.A. Miller

Three generations of the Red Cloud family, Gordon, Nebraska, 1909.

views-of-the-reservation-portrait-woman-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

A studio portrait of an unidentified woman, circa 1910.

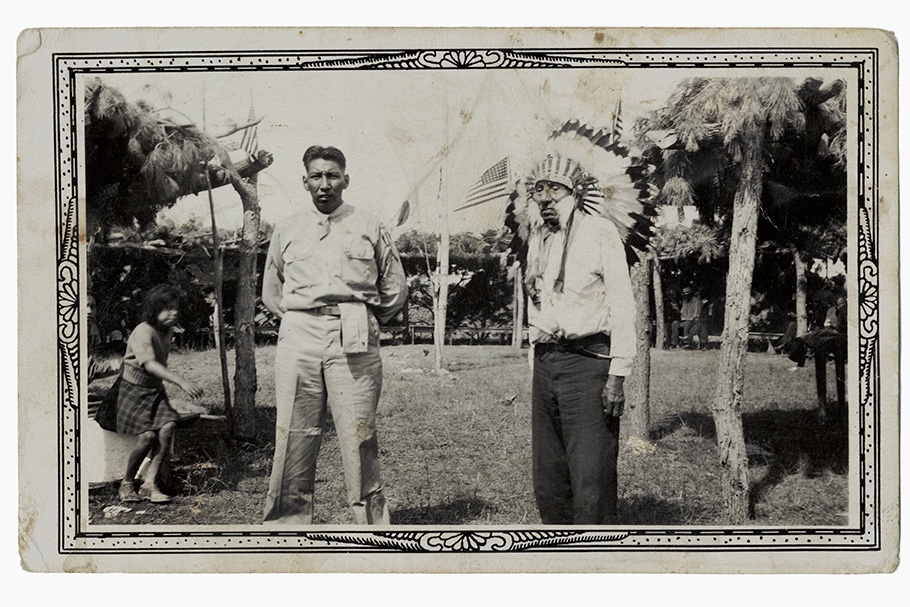

views-of-the-reservation-headdress-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

A Potato Creek powwow in celebration of the safe return of Ernest Blue Legs from World War II, circa 1945.

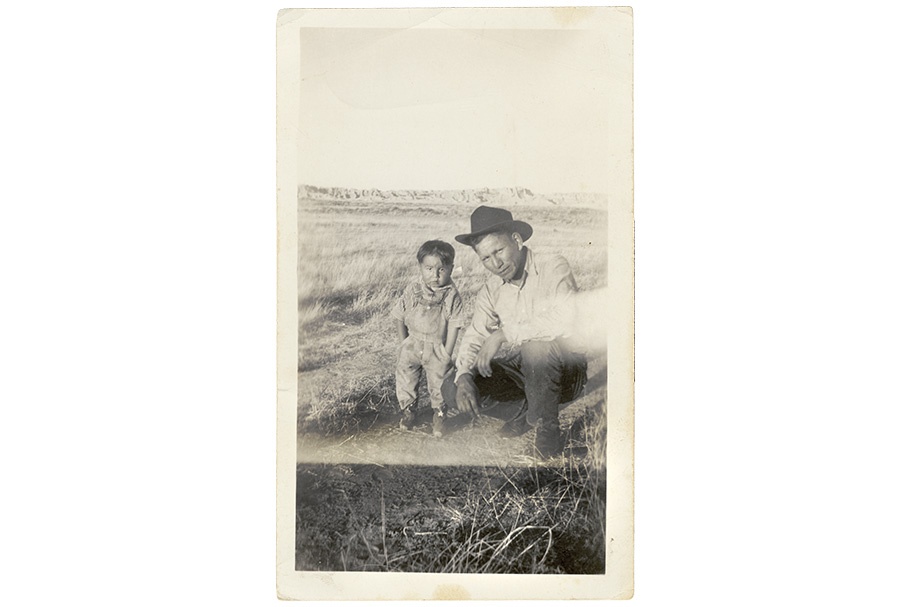

views-of-the-reservation-boy-and-man-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Orville Reddest as a boy and Moses Bull Man, circa 1946.

views-of-the-reservation-kids-sitting-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Orville Reddest and Andrea Reddest, whose married name became Marshall, circa 1946.

views-of-the-reservation-portrait-woman-outside-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Ellen Hollow Head, who married Eugene Reddest, circa 1940.

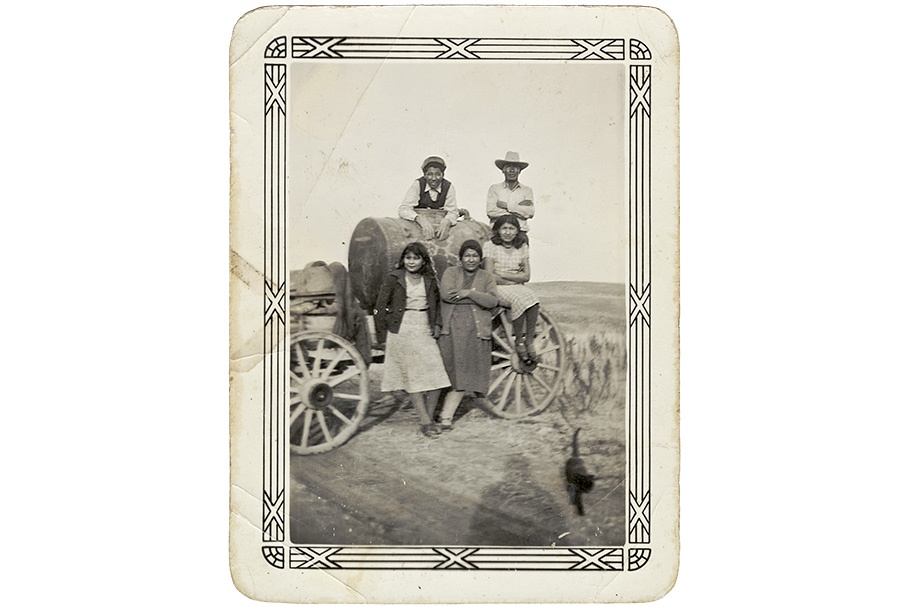

views-of-the-reservation-portrait-family-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Ernest Blue Legs (top left), Charlie Red Horse (top right), and their three sisters (left to right: Ellen, Sarah, and Martha Hollow Head) hauling water, circa 1940.

John Willis received his MFA in photography from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1986. Since then, he has been teaching and exhibiting photography that aims to highlight social issues. He is currently a professor of photography at Marlboro College, and is the co-founder and executive director of two photography programs: The In-Sight Photography Project, which offers courses to young people regardless of their ability to pay; and the Exposures Cross Cultural Youth Arts Program, which brings together young people from diverse backgrounds to share photography and life stories.

Willis has been awarded multiple fellowships from the Vermont Council on the Arts and the Vermont Arts Endowment. His work is in various permanent collections, including the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the George Eastman House, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Library of Congress, the National Museum of the American Indian, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Willis’s exhibitions include solo shows at the Blue Sky Gallery, Portland, Oregon; the Photographic Resource Center, Boston; and the Oglala Lakota College on Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota. His images have appeared in publications, including LensWork, Orion Magazine, and Flesh and Blood: Photographers’ Images of Their Own Families. In 2005, Willis collaborated on a book project with photographer Tom Young called Recycled Realities, co-published by the Center of American Places and Columbia College. Willis’s most recent book, Views from the Reservation, was published in 2010. He was the recipient of a 2011 John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in Photography.

Dwayne Wilcox is an enrolled member of the Oglala Lakota people who was born and raised on the Pine Ridge Reservation. He currently lives and works in Rapid City, South Dakota. His artwork has won many awards, including Best of Division at the Heard Museum Indian Art Market in 2008 and First Place at the Santa Fe Indian Art Market in 2007. His artwork has also been commissioned by museums throughout the country, including the C. M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana; the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College; and the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

John Willis and Dwayne Wilcox

John Willis

Mitakuye Oyasin. These words, spoken at the beginning and end of Oglala Lakota prayers, translate as “all my relations.” Together, they are an acknowledgment of all things being related, a deliberate reminder that all we do will affect all else and the balance within the world.

When thinking of the Pine Ridge Reservation, what do people imagine? What are the preconceived notions that outsiders carry about the place, the culture, and the people and their way of life? Pine Ridge is the Oglala Lakota Tribe’s home, a territory that once covered an area from Minnesota to the sacred Paha Sapa (Black Hills) of southwestern South Dakota and eastern Wyoming. Today, the reservation has been reduced to an area of approximately 50 by 100 miles. Both outsiders and native peoples know of Hollywood’s representation of traditional Native American culture; often it has been based on a reductive portrayal of the Lakota and other indigenous people of the Great Plains and American West. Most of us have heard of Wounded Knee, the massacre there in 1890, and its occupation by the American Indian Movement and its supporters in 1973. Currently, Pine Ridge includes some of the poorest counties in the United States, with an average per capita income of $4,000, low life expectancy, and high rates of infant mortality, suicide, diabetes, alcoholism, and unemployment. How or why would one choose to ignore these facts when speaking of reservation life? Yet how much do these statistics really tell us? For on the reservation, there is immense openness, beauty, and warmth.

For the past 19 years, I’ve traveled regularly to Pine Ridge. My annual visits to the reservation have been to the region known as Lost Dog Creek, where I have been a guest of Eugene Reddest and his family. The photographs in this collection are a sampling of what I have done and seen during my visits over the years. As an outsider, I have always been welcomed by the Reddest family. Their hospitality and willingness to share their lives and stories about their community has deepened my respect for them and my relationship with the Lakota people.

I came to exhibiting these images with some difficulty. I am aware of the debates and issues that can arise when photographers, especially Caucasian photographers, enter the lives of indigenous people. As history tells us, photography played a large role in the U.S. government outlawing all traditional Lakota spiritual practices and rituals for 40 years during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Photography and other tools of documentarians were used to convince the U.S. government that the native people were practicing so-called “barbaric” rituals. For those 40 years, traditional Lakota practices were kept alive by those willing to risk imprisonment by secretly conducting ceremonies while hiding in the plains. Today, these practices are again legal and growing in popularity, but the distrust of photography and documentarians still exists, and understandably so.

Yet the greatest motivation for exhibiting these images came from within Pine Ridge, from the patriarch of the Reddest family, Eugene Reddest himself. During one of the last times we shared together before his passing, Eugene wanted to know how I would use the photographs I had made of his family and friends. I told him that I planned to only use them as mementos for his family, mutual friends, and to keep for myself. He requested that I use them in ways that might help his family and people.

I have made my book and its corresponding exhibition with Eugene very much in mind. Both include archival photos from the Pine Ridge community, vibrant ledger paper drawings by Oglala Lakota artist Dwayne Wilcox, youth poetry, elders’ words, a CD of traditional music, and essays, as a way to offer the viewer a wider range of representation of Lakota cultures. I hope that giving this material a more public audience will have some value as Eugene hoped.

Photographer’s note: I would like to dedicate this work to Eugene Reddest and Tommy Crow, his cousin and best friend from Pine Ridge who befriended me. I am grateful for the openness that Eugene and Tommy showed me. It truly was an inspiration to have known them. All royalties from the book are being donated to KILI Radio, Voice of the Lakota Nation. Mitakuye Oyasin.

—John Willis, November 2011

Dwayne Wilcox

Pictographs, our traditional visual language, were once put on familiar things such as hides. That changed with the disappearance of the bison and the loss of freedom to hunt, when the reservations bound native people. The first paper on the Great Plains was found in used ledger books from white merchants. That paper became a new medium to my people, in addition to the colored pencils and inks available for trade. Like beads and beadwork, which were also traded, drawings on paper from ledgers have become a traditional form of art called ledger art.

I have been drawing all my life but in 1988, I committed myself to doing what I was put on this road for: recovery and enlightenment. So I worked very hard to find and research ledger drawings wherever I could, including at the Smithsonian Institution and other museums that collect these drawings. To the many friends who were helpful in this pursuit, thank you. My friends and family influence my work by the way they communicate and tell a joke or a story. In the Lakota way, humor is medicine and helps us heal. That is why there are such figures as the Sacred Clown. My drawings are meant to reflect that kind of humor and the traditional lifeways. This is what I see as everyday life.

—Dwayne Wilcox, November 2011

U.S. Programs

The Open Society Foundations’ U.S. Programs is working to build a vibrant society that invites all people to participate fully in civic, economic, and cultural life. The program encourages critical debate, respects diverse opinions, and protects fundamental human rights, dignity, and the rule of law. U.S. Programs recognizes that power is not broadly shared and that inequalities cut across multiple lines, including race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and citizenship. Several initiatives within U.S. Programs—the Democracy and Power Fund, the Equality and Opportunity Fund, the Strategic Opportunities Fund, and the Transparency and Integrity Fund—provide support to Native American organizations and communities working on issues such as preserving and advancing Native American art, reclaiming and redefining representations and perceptions of Native American society, protecting tribal sovereignty and other Native American rights, strengthening access to public interest news and information, and ensuring and increasing affordable access to the internet and digital technology.